The Egyptian revolution appears to present a “gender paradox.” On the one hand, women have been marginalized in many formal political institutions since the downfall of Hosni Mubarak. On the other hand, representations and images of women and women’s bodies have been ubiquitous. Representations of women through media and art, as well as the regulation of women’s sexuality through state laws and constitutions are an essential part of defining national identity and national difference, marking the boundaries between “them” and “us” and constituting the national polity. Representations of women and particular gender orders are also used as symbolic markers to differentiate between past and present. However, a consideration of images and representations is not only about mechanisms of governmentality but refocuses our attention upon agency and the importance of bodies in the revolution. Representations of gender and sexuality should not be reduced to a binary of resistance/domination. Rather, different representations illustrate how bodies become (re-)negotiated, (re-)signified, and (re-)defined in response to and in struggle over political transformations. Competing representations of Egyptian womanhood in the current period are intrinsic to the struggles over citizenship rights, the boundaries of the Egyptian nation and the future of Egypt’s polity in the current revolutionary process.

From The “Empowered Revolutionary Woman” to the “Victim of Violence”

The “empowered revolutionary woman,” protesting in Tahrir Square, was a regular feature of images of the 25 January uprising. In the western media, the presence of women came to signify the progressive-ness of the revolution (i.e. it must be democratic because there are women participating), potentially displacing orientalist stereotypes of the “oppressed Muslim woman.” Many Western observers have conflated women’s agency in the revolution with feminist desires, obscuring or erasing the multiple objectives of and motivations for women’s agency. Many Egyptian women were appalled at Western media assumptions that they were “liberated” by the January 25 Revolution. Such representations erased the long history of Egyptian women’s defiance and resistance activities, most recently in the decade prior to the 2011 revolution. Many Egyptian women protesters were also keen to stress that “women and men stood side by side in the revolution” calling for the downfall of Mubarak. Their objectives were not immediately those of women’s liberation or women’s rights. However, as the transition process unfolded, and women were excluded from political institutions, many began to express concern that women’s participation in the protests was not being translated into their participation in the political transition. Indeed, on International Women’s Day, less than one month after the fall of Mubarak, women marching for women’s rights were harassed and “told to go back home” by gangs of men in Tahrir Square.

The legitimacy of the Egyptian female revolutionary has been increasingly contested in the post-Mubarak period through the use of sexualized violence against women protesters. Under the rule of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the military undertook “virginity tests” against women revolutionaries, widely condemned by Egyptian and international human rights organizations. The “blue bra woman” (that is, a video of a woman being dragged across Qasr al-Einy Street and beaten by military police forces in December 2011) has become an iconic image of SCAF-sponsored violence. The shock of the violence is intensified by the fact that the woman is wearing a veil, which is tugged away from her body. More recently, there has been an alarming increase in sexual assaults against women protesters in and around Tahrir Square during demonstrations marking the second anniversary of the January 25 Revolution. Women have come forward to give testimonies publicly describing how large gangs of men have surrounded women, ripping away their clothes and grabbing and violating their bodies. The violence and harassment experienced by women protesters in and around Tahrir Square is tragically ironic given the representation of the square as a “sexual harassment-free zone” during the eighteen-day uprising.

[Resignifying Gender Norms. Photo by Nicola Pratt]

Gender, Sex, Nation, Counter-Revolution and Geopolitics

Many activists claim that the violence against women is organized and politically motivated, including by the Muslim Brotherhood, to intimidate women from protesting. The targeting of women in this way operates to terrorize women out of the public sphere as well as delegitimizing women protesters. Islamists in the Shura Council have blamed female protesters "who insist on demonstrating with men in unsecure areas" for the violence they experience. Public violence against women disciplines the “authentic” Egyptian woman as one who is compliant with rather than defiant of existing gender and sexual norms. Women’s modest behavior is, for certain political trends, symbolic of the Egyptian nation, and those who transgress these norms should be punished. A senior Egyptian general justified the virginity tests as necessary to prevent female protesters from accusing the military of rape and told CNN that the arrested women “were not like your daughter or mine. These were girls who had camped out in tents with male protesters.” Moreover, the use of violence against women is justified in terms of maintaining “national” values, which are intertwined with “Islamic values." The Egyptian government’s opposition to a UN declaration against violence against women at the UN in New York in March 2013 was based on its content being in contradiction with “established principles of Islam,” undermining “Islamic ethics,” “destroy[ing] the family,” and leading to the “complete disintegration of society, and would certainly be the final step in the intellectual and cultural invasion of Muslim countries.”

Public violence against women also plays an important counter-revolutionary role. The glorification of women’s participation in the January 25 Revolution is, in retrospect, considered by certain political trends to be exceptional rather than representing a redefinition of existing gender norms. This exception was deemed necessary to rectify the gender order that had been reversed under Mubarak’s regime, as a result of decades of dictatorship and impoverishment. The need to restore a lost gender order is implied by Asmaa Mahfouz in her impassioned plea, which went viral on YouTube at the beginning of 2011. In the video, she said: “If you think yourself a man, come with me on 25 January. Whoever says that women should not go to protests because they will get beaten, let him have some honor and manhood and come with me on January 25.”

In challenging Egypt’s men to join her in demonstrations, Mahfouz provided an implicit critique of the state of gender under Mubarak’s regime, suggesting that men had become like women, whilst women, like Mahfouz, had become like men, courageously facing up to police brutality for the sake of their honor. Whether Mahfouz’s words had a widespread impact or not, her words constitute a strategic reversal of the discourse of ‘masculinity-in-crisis’ that became central to local and global security governance under Mubarak. The reclaiming of masculine dignity was a theme among many of the placards displayed in Tahrir Square (as Karima Khalil’s photographs illustrate). And the restoration of masculine dignity came to depend upon a reestablishment of a gender hierarchy rather than its dismantlement. The forcible exclusion of women from demonstrations through sexual violence is meant to mark the end of the “revolutionary process” (and, with it, the demands for social justice and accountability for past regime crimes) and the return to “normalcy,” including normative gender relations.

Western media narratives that equated women’s agency in the revolution with women’s liberation have given way to a narrative that “the revolution is threatening women’s previous gains” not only because women are increasingly victims of public violence but also because rights that were established under the Mubarak regime are now under threat. For example, the very dubious women’s quota introduced in 2005 (under Mubarak) has been cancelled, the much debated khula‘ law of 2000 is being reconsidered, and the National Council for Women, headed by former First Lady Suzanne Mubarak, is being marginalized by President Morsi. The new regime’s reversal of what many Egyptians call “Suzanne’s laws” is part of marking the transition from the previous, nominally secular regime, supported by the West, to the new Islamist government. However, for the Western media, the transition marks the return of the orientalist imaginary of the “victimized” Muslim/Arab woman as the primary trope through which the West understands the Arab world.

[Sitt Al-Banat. Photo by Nicola Pratt]

Sexual Politics, Revolution, Resistance and the West

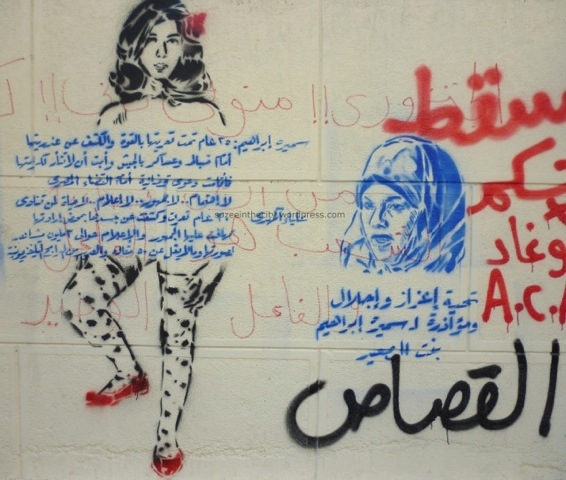

In response to the violence against women and efforts to exclude them from the public sphere, revolutionaries have promoted their own counter-narratives and (self-) representations of women. The case of Samira Ibrahim, who raised a court case against the military for having been subjected to so-called virginity tests by SCAF, has been supported by revolutionaries and her bravery has been celebrated through graffiti images. Another ubiquitous graffiti image is that of “sitt al-banat,” representing the “blue bra girl.” Through these and other representations, women are reinscribing their victimization as resistance against dictatorship, and in the process redefining “authentic” Egyptian womanhood.

One particular image of an Egyptian woman has provoked much discussion amongst Egyptians and internationally, that of Aliaa El-Mahdi, aka the “naked blogger,” and whether the act of publishing herself naked on her blog was an appropriate form of protest. In Egypt, her posting elicited a lot of debate and condemnation from many quarters—including some revolutionaries. April 6 movement publicly denied that she was a member of their organization. El-Mahdi’s nudity was deemed by many, even those resisting the old order, to be too transgressive of existing sexual norms. She is negatively contrasted with Samira Ibrahim (see graffiti shown here).Ibrahim’s resistance to her victimization by SCAF is fought not on the terrain of sexual politics but on “political grounds.” In so doing, she defies gender norms without transgressing sexual norms, defining the “meaning of the revolution.”

[Samira Ibrahim versus Aliaa El-Mahdi. Photo by Suzeeinthecity]

El-Mahdi has been welcomed in Europe, as illustrated by her more recent naked protest in Sweden with the “sextremist” group Femen against the new Egyptian constitution and President Morsi. As Sara Mourad writes, in the video of the Femen protest, “Alia is no longer a naked Egyptian female body; it is the naked body of an Arab Muslim woman, painted with an anti-Islamic message in English, in an Islamophobic Europe.” El-Mahdi’s agency becomes legible to Western media as it is re-presented as resisting the “barbaric Muslim men.”

Samira Ibrahim represents a contrasting case. She was invited to the US in March to receive an award by the US government for her bravery (the International Women of Courage awards). This award was then withdrawn because of her alleged anti-American and anti-Israeli tweets. This episode illustrates how Western recognition of Muslim women’s agency is contingent upon her representing resistance to the barbaric Muslim man and not the barbarism of the West and its allies. Simultaneously, the inability of the West to appropriate the agency of Samira Ibrahim into orientalist narratives potentially re-authenticizes her performance of femininity within the Egyptian context.

Gender, Revolution and Sacrifice

Thousands of martyrs have become victims of the violence committed against protesters, both during the eighteen-day uprising, but even more so during subsequent demonstrations. Predominant images of martyrs in street murals, graffiti, and popular memorials are of young men (despite the fact that there exist female martyrs). In the image of the mother of the martyr, seen on graffiti around Cairo, female agency is reduced to that of a mother grieving for her dead child. Her tears are a symbol of the sacrifices that have been made for the revolution and simultaneously incite onlookers to continue the revolution to avenge the martyrs. Her image complies with existing gender norms of women as mothers, sacrificing for their families, their communities and, ultimately, their nation. This image may be contrasted with that of the “empowered female revolutionary,” who is represented as defying gender norms through her participation in protests and her resistance of dictatorship. However, by reading the image of the empowered female revolutionary together with that of the mother of the martyr it is possible to interpret both as symbolizing the sacrifices made for the revolution –one having sacrificed her body and the other her son. Arguably, both images are circulated as a means of encouraging others to sacrifice and to continue the revolution. Reading these two images together raises questions about the degree to which representations of women that circulate in Egypt’s public spaces challenge existing sexed-gender norms or whether existing sexed-gender norms are being resignified in revolutionary ways—or perhaps both at the same time.

[Mother of the martyr. Photo by Nicola Pratt]

Egyptian Femininity, Citizenship and the Future Polity

The competing representations of Egyptian femininity in the post-Mubarak period challenge, reinscribe and/or reaffirm notions of sexuality, gender and nation and, in so doing, reflect the contours of the competition for power among different political and social actors. Whilst the Muslim Brotherhood’s capture of state institutions enables them to define “authentic” Egyptian femininity in state laws, nevertheless, these efforts are continually challenged by the re-signification of womanhood in Egypt’s squares and streets, as well as in social media. By paying attention to rival representations and performances of “authentic” Egyptian femininity, we can see a terrain in flux, where there still exist spaces to re-imagine and re-create identity, citizenship and the polity (as opposed to the more pessimistic conclusions that are being drawn about Egypt’s transition and the development of women’s rights).

* Thank you to participants in the “Women, Culture and the 25 January 2011 Revolution” workshop, Ayn Shams University, March 2013, for feedback and suggestions on earlier versions.