The story of nonmovements is the story of agency in the times of constraints

- Asef Bayat

An international non-governmental organization, Women on Waves, collaborated with a local Moroccan collective, Mouvement alternatif pour les libertés individuelles (MALI), in a direct action ship campaign to promote safe abortion access in Morocco in October 2012. Women on Waves and MALI operate under the principle that a woman’s right to access a safe abortion is a fundamental human right. Based on Asef Bayat’s theory, medical abortion, in the particular political and cultural context of contemporary Morocco, can fit into the model of a social nonmovement. According to Bayat, a social nonmovement, defined as the contentious actions of atomized individuals, has the possibility for a pivotal moment of transformation into a social movement, conceptualized in a Western, hegemonic discourse as something collective, visible, and organized. In an inverse sequence of this model, a social movement would have the capacity to incite and inform social nonmovement. This model, a social movement to a social nonmovement, has yet to be articulated or empirically demonstrated. Additionally, the social nonmovement as the consequence and not the precursor of social movement is a different entity that I call “conscious social nonmovement.”

An Inversion of the Traditional Trajectory

Sociologist Asef Bayat (2010) writes about the model of what he calls social nonmovement. The sociological concept of social nonmovement is “...the collective actions of noncollective actors” (Bayat, 2010, p.14). The various actions that individuals take in their everyday lives to attain personal freedoms while living in a society that prohibits basic human rights characterize social nonmovements. While these contentious practices occur invisibly and in isolation, Bayat (2010) asserts that at a moment when political opportunity arises, the atomized individuals of social nonmovements have the capacity to quickly join each other and transform into a visible collective. He also emphasizes that a social nonmovement is highly contextual as its existence depends on necessary political, social, and economic conditions. Women on Waves and MALI organized a direct action ship campaign and launched a safe abortion hotline. This transnational collective of committed individuals created a very public social movement dedicated to bring choice to women in Morocco, even when the national law prohibits it. The human rights principles of freedom of expression and information justified and propelled this project. Women on Waves and MALI widely disseminated the instructions for how women in Morocco can induce a safe abortion themselves. Since the hotline’s creation, hundreds of women in Morocco have called and some have successfully induced their own safe abortion. The women who engage in this act are not visible. They are not on the forefront of international media or even activists themselves. They are ordinary women living in Morocco who now have the information needed to control their physical bodies. While in Bayat’s theory (2010), social nonmovement may transform into social movement, I have constructed an inverse model: social movement to social nonmovement. This is a new theoretical process that must be explored. I therefore examine the direct action in Morocco as a case study of a social movement that has the capacity to provoke social nonmovement in the particular political and cultural context of Morocco.

Women on Waves: The International Actor

Unsafe abortion is a global issue of public health and human rights that threatens the physical and psychological health of women. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), unsafe abortion contributes to thirteen percent of maternal mortality worldwide (Åhman & Shah, 2008). Many countries have laws that prohibit safe and affordable abortion access. A woman who attempts to have an abortion in these restrictive settings may use dangerous methods that can result in morbidity or an untimely and preventable death. In 2003, forty-two million abortions occurred worldwide; twenty-two million that were safe and twenty million that were unsafe. In 2008, there were 21.6 million unsafe abortions globally, most of which occurred in developing countries, contributing to forty-seven thousand maternal fatalities (Åhman & Shah, 2008).

Founded in 1999 by Rebecca Gomperts, MD, MPP, Women on Waves is an international non-governmental organization that provides safe abortion access where it is illegal and/or highly restricted through working with local partners in various countries. Employing a direct action method, Women on Waves sails to countries where abortion is illegal in order to provide safe abortion access. In international waters, twelve miles out to sea, the laws that govern a ship are those of the country in which it is registered. Therefore, operating at sea on a Dutch ship, Women on Waves can legally administer the abortion pill to women from these other countries. Women board the ship at a harbor in their native country, sail twelve miles to international waters, and then receive Mifepristone (RU-486). Since 2001, Women on Waves has sailed to Ireland (2001), Poland (2003), Portugal (2004), Spain (2008), and most recently, Morocco (2012). These ship campaigns create public awareness and gain attention from ruling political parties in specific countries that seek advancements in access to reproductive healthcare. The direct action method of the ship campaign is not intended to be a practical solution to a long-term problem. The ship campaigns can help a few women, but their power is largely symbolic as the act of strategy itself is harnessed to create political discussion and controversy. Women on Waves has also initiated safe abortion hotlines in Ecuador, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Pakistan, Indonesia, Kenya, and Morocco, and has trained grassroots women’s organizations in several southeastern African countries. In addition to the direct action tactic with the ship, Women on Wave’s mission is to work in collaboration with local activist groups within restrictive countries to provide trainings about safe abortion and other reproductive health topics.

The Context of Morocco

In the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, unsafe abortion is the cause of approximately eleven percent of maternal deaths (Dabash & Roudi-Fahimi, 2008). In Morocco, approximately six to eight hundred abortions are performed daily (“Association marocaine de,”). Doctors and/or medical professionals perform five to six hundred of these procedures for a very high price, since it is an illegal act. However, non-medical persons who may employ dangerous methods that can cause permanent injury and/or death perform approximately one hundred fifty to two hundred of the total procedures (“Association marocaine de,”). This daily projection of six to eight hundred abortions is a conservative estimate of how many abortions actually occur because this procedure is illegal in Morocco and is therefore difficult to obtain precise statistics. Abortion is only permitted to preserve the woman’s health and spousal authorization is mandatory (“Morocco, abortion policy,”). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health to be both physical and mental ("Who definition of,"), so that preserving a woman’s health should encompass more than a consideration of her physical vitality. However, Morocco’s penal code prohibits abortion and it is difficult to acquire legal approval for a case in which a woman’s life is not in immediate danger.

MALI: The Local Actor

In each ship campaign, a local group (or groups) within the country invites the Women on Waves to help them promote a message of access and legalization for safe abortion. A long process of planning and collaboration must take place in order for the project to be successful. Recognizing the need for safe abortion access in Morocco, Women on Waves formed a partnership with a local Moroccan collective, the Mouvement alternatif pour les libertés individuelles (MALI) to initiate a ship campaign to raise awareness about this issue that threatens the health of women. These two groups also launched a safe abortion hotline for women in Morocco. MALI is a Moroccan collective well known for their dissident activities and struggle for a democratic and secular society. The activists of MALI believe in equal rights for the LGBTQ community and believe that the government utilizes religion as a tool of oppression. In 2009, they gained notoriety for an action during the month of Ramadan. To protest the strict religiosity of their society, they decided to have a public picnic during the holiday, an act that article 222 of the penal code forbids ("Morocco: End police," 2009).

Moving beyond the traditional framework defined by the relationship between a medical professional and a woman desiring an abortion, Women on Waves and MALI assert that a woman has the mental and physical capacity to induce her own abortion. Aside from a medical emergency situation, a medical professional is not needed for the abortion procedure because a woman’s right to govern her own physicality allows her the freedom to make and follow through with a termination of her pregnancy when she has the correct information about how exactly to do this safely. Drawing on article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that guarantees the right to freedom of opinion and the dissemination of information (“The universal declaration,”), Women on Waves seeks to provide women with the tools necessary to complete their own abortion even when particular local and/or national law may prohibit access.

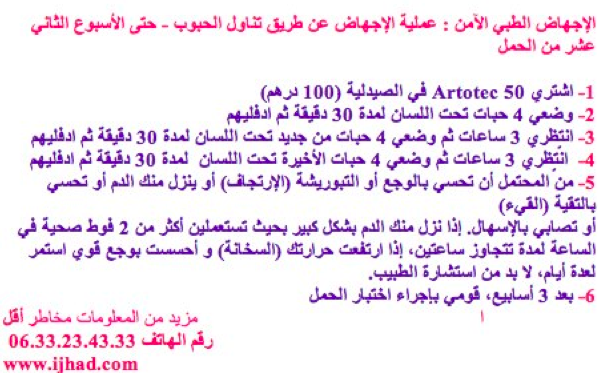

Therefore, the ship campaign, a direct action strategy, which took place from 3 October 2012 until 9 October 2012, had the ultimate goal of launching a safe abortion hotline for women in Morocco as a means to disseminate information about the safety and availability of a medicine called Misoprostol. Misoprostol, which can be used to induce a safe abortion at home up until twelve weeks of gestation, is available in Morocco over the counter in a pharmacy without a prescription under the brand name Artotec. Misoprostol is on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines (Who model list, 2011) and has been tested extensively to prove its safe and effective usage to induce an abortion. Misoprostol can also treat rheumatoid arthritis and to prevent gastric ulcers, which is why it is so readily and legally available in pharmacies in Morocco[1].

Women on Waves and MALI identified that women did not know about the availability of Artotec and how to use it safely and effectively to terminate a pregnancy. As a result, Women on Waves and MALI planned a direction action to provide women with the knowledge needed to take control of their own bodies. Additionally, the international media attention garnered from this ship campaign put the issue of unsafe abortion on the political agenda of the Moroccan government to create discussion about liberalizing the currently restrictive law.

Medical Abortion as a Social Nonmovement

Bayat (2010) articulates the theory of social nonmovement as the actions that individuals take in their everyday lives to attain basic freedoms that the government prohibits. Dispersed individuals, not a traceable or visible collective, execute these contentious actions. In this sociological model of what might be also referred to as invisible resistance, particular practices in context fall into this framework. The urban dispossessed stealing power from the municipalities and women in Iran pushing back the required hijab are two examples of social nonmovement, according to Bayat (2010). Both of these actions are not extraordinary; they are ordinary practices that are only considered rebellious because of the particular situation in which they occur.

Medical abortion, in the particular social and political context of contemporary Morocco, can also be conceptualized within the paradigm of social nonmovement. In Morocco, abortion is mostly illegal and restricted by the government, unless it is to save the life of a woman. Medical abortion, a procedure induced with pills, is an alternative possibility within the Moroccan locale because of the fact that Artotec is readily available over the counter in a pharmacy, without a prescription. A woman does not need the supervision of a physician or medical professional to induce her own abortion with Artotec pills if she has the correct medical instructions about the number of pills to take and the time intervals in which to take them. A woman can complete a medical abortion on her own effectively and safely up to twelve weeks gestation (World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research, 2012).

Now, let us examine if medical abortion in Morocco has the potential to fit the criteria for social nonmovement as defined by Bayat (2010). First, medical abortion is certainly action-oriented and not ideologically driven: it is an act performed by a woman on her own body. Second, medical abortion is also a direct practice, despite government sanctions as abortion is severely restricted by the Moroccan penal code. Third, medical abortion could also surely be considered an ordinary practice of everyday life. While many reproductive health and sexual health advocates strongly articulate that with comprehensive sexual education and better access to contraceptives millions of abortions could be prevented. This is undoubtedly true, and I do not mean at all to diminish the importance of comprehensive sexual education and access to contraceptives. However, this framework also heavily contributes to the stigma of abortion as a practice that should ultimately be abolished if the correct measures are taken. What should be eradicated is the enormity of maternal morbidity and mortality; a direct result of when women do not have the access needed to safe abortion methods.

The reality of the world in which we live is that many countries do not and will not have, in the near future, institutionalized comprehensive sexual education and/or access to affordable contraception. The termination of pregnancy, therefore, needs to be acknowledged as a critical aspect of overall family planning. In this way, abortion can be normalized with the practices of stealing electrical power or pushing back the hijab. This is not meant to be a crude parallel that trivializes the decision of a woman to terminate her pregnancy. Instead, placing “do-it- yourself” medical abortion in a category with other contentious practices of social nonmovement is meant to illustrate that abortion is not an exceptional occurrence and that it should be included in the discussion of exercising personal rights over the physical body.

[Safe abortion instructions sticker in Arabic. Image provided by author.]

Eventful Change

The Women on Waves and MALI direct action ship campaign for safe abortion occurred between 3 and 9 October 2012. No abortions were performed in international waters. However, this was not at all perceived as a failure of the campaign because the ship is never meant to be a practical solution to long-term and pervasive problem of unsafe abortion. Unsafe abortion in Morocco is an issue of social inequality because the reality is that despite its illegality women of high socio-economic-status have enough money for a physician to perform this procedure safely in a private clinic. In contrast, women who suffer economic hardship do not have access to safe methods because they cannot afford the high price. Therefore, women of lower socio-economic-status are marginalized, unable to obtain safe services, and may therefore resort to dangerous and life-threatening alternatives. The collaborative efforts of Women on Waves and MALI continue to this day because of the launch of the safe abortion hotline that creates access for women where there seemingly is none.

Women who perform their own abortion by using the medication Artotec engage in an individualized action that is against government sanctions[2]. Women on Waves and MALI mobilized for the ultimate purpose of disseminating the information that Artotec is available in Morocco over the counter of a pharmacy and that it can be purchased without a prescription for the equivalent of ten US dollars. During the campaign, the ship successfully reached territorial Moroccan waters because Women on Waves employed the extremely effective Trojan horse tactic; the ship was already docked inside Marina Smir when the Moroccan authorities placed the harbor on lockdown and brought in navy warships to block the anticipated arrival of the ship. The emergence of the ship and its victorious sail in the closed port before its unconstitutional search and deportation by Moroccan police made a very strong statement that the collaborative effort of Women on Waves and MALI could not be stopped. While the ship is both the tangible Trojan horse and physical embodiment of the transnational public sphere (J. Guidry, M. Kennedy & M. Zald (Eds.), 2000), the medical protocol of how to perform a safe medical abortion is the intangible version of the Trojan horse. These instructions are a particular piece of knowledge about something that was already inside Morocco (Artotec) and Women on Waves and MALI used the moment of the ship campaign to reveal its existence and in-country availability, which has the potential to transform the lives of women.

Transformational Social Science

Medical abortion in the context of contemporary Morocco should be categorized as a conscious social nonmovement that has been incited by a social movement. Women on Waves and MALI, joined together for a campaign that falls into the Western, hegemonic construction of social movement. This direct action brought extreme visibility to a specific issue, augmented with powerful symbols: a ship and multiple banners. One of the banners had a telephone number for the safe abortion hotline. Therefore, the combination of the ship’s action and the inception of the safe abortion hotlines exemplify “social movement” in its classical form. Using a unique nautical method, the direct action intended to widely disseminate the medical abortion instructions for Artotec to women in Morocco. These target women are not activists or part of any organized collective. The specific medical protocol is a piece of knowledge that can guarantee freedom and dignity in a context of state control that prohibits the basic human right to a safe abortion.

There is a critical differentiation between medical abortion as social nonmovement as the result of and not the cause of social movement, which is why I call it “conscious social nonmovement”. When Bayat (2010) describes social nonmovement as the precursor to social movement, he is explicit that the individuals who engage in these rebellious actions do so without political consciousness. The practices are merely a mechanism to survive with dignity (p.58). It is only when the ability to continue do authorities threaten these practices, resulting in the actors developing a political consciousness in their behaviors. In the reverse sequence, when social movement is the first stage, it was widely publicized and acknowledged that medical abortion violates the Moroccan law as it is enforced. Therefore, when women subsequently purchase medical abortion, it becomes not simply an act to survive with dignity but something that is performed with a political consciousness against the repressive status quo. The “conscious” part in this label draws inspiration from Marx’s distinction of when the working class transforms from a group of individuals with the same goal of combatting the capitalists into a “class for itself” (1963, p.173). It is only when the workers become a “class for itself” that a class-consciousness emerges. For conscious social nonmovement, the same kind of awareness for political contention in the action becomes realized, but it is a transformation within the individual and not within a class. Thus, the individual of conscious social nonmovement is an “individual for him/herself” as opposed to an “individual in him/herself”. Therefore, the element of political consciousness in the Morocco case study of the nonmovement resulting from movement is a point of deviation from Bayat’s framework (2010). These differences, however, should not exclude medical abortion in Morocco, a contentious practice performed by noncollective actors, from being classified as a social nonmovement. Instead it should be recognized as a new kind of social nonmovement: the conscious social nonmovement.

References

Åhman, E., & Shah, I. (2008). E. Åhman (Ed.), Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008 (6th ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization

Bayat, A. (2010). Life as politics: How ordinary people change the middle east. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Dabash, R., & Roudi-Fahimi, F. (2008). Abortion in the middle east and north africa. In Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

Guidry, J. M. Kennedy & M. Zald (Eds.), (2000). Globalizations and Social Movements: Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Marx, K. (1963). The poverty of philosophy. (5th ed.). New York: International Publishers

Singh, S., Wulf, D., Hussain, R., Bankole, A., & Sedgh, G. (2009). Abortion Worldwide: A Decade of Uneven Progress. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

[1] Misoprostol also has other gynecological indications that include the induction of labor and prevention and treatment of post-partum hemorrhaging (PPH).

[2] Taking Artotec for various medical indications in Morocco is not illegal, since it is a medicine that is readily available in pharmacies. However, taking Artotec with the intention of inducing an abortion violates the Moroccan penal code.