Andrew Gardner and Autumn Watts, editors, Constructing Qatar: Migrant Narratives from the Margins of the Global System. Smashwords, 2012.

Jadaliyya (J): What made you put together this book?

Andrew Gardner (AG): Migrants in the Gulf states have been a central focal point in my research for more than a decade now. Over that decade, I definitely noticed that the portions of my research and my presentations that truly resonated with my audience were oftentimes not the scholarly and theoretical acrobatics that seemingly comprise so much academic activity today, but rather the migrant stories and narratives that have often served as the foundational data in my ethnographic analysis. The principal idea behind this book was to avoid the tedious and byzantine scholarly conversation about migration, and to instead simply provide readers with the narratives themselves. My collaborators and I also came to understand how this approach allowed readers to reach their own conclusions about migration and the predominant migration system in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. In essence, we envisioned these migrant narratives as an unguided tour of these migrants’ lives and experiences.

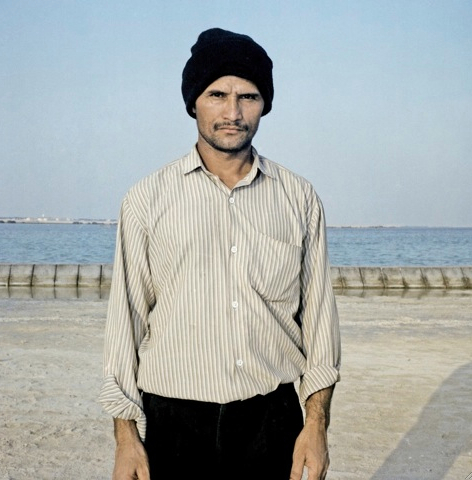

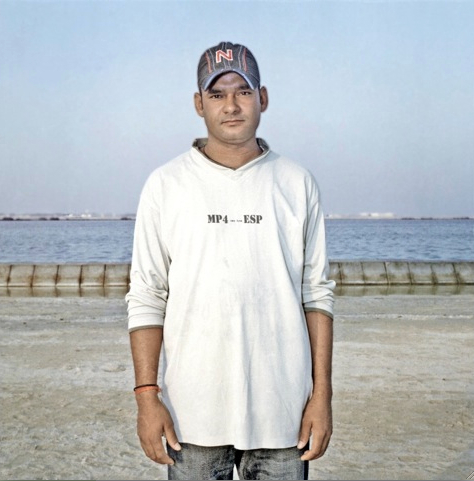

I think the process we used to assemble this book is also noteworthy. The migrant narratives were gathered by a set of six student-researchers at various universities in Qatar. I trained them in the technique of the ethnographic interview, and they individually found their way to the diverse set of migrants whose stories appear in the book. The students interviewed each migrant several times, and with those interview transcripts in hand, they worked with my co-editor and collaborator, the writer Autumn Watts, to craft coherent narratives from the interview transcripts they had gathered. Among other goals, we aspired to keep our gaze fixed on the diversity of migration experiences, to convey that diversity with this project, and to allow readers to grapple with that diversity as well. We were also lucky be able to include some of photographer Kristin Giordano’s work in the eBook. Her photographs of labor migrants in Qatar resonate with many of the themes and goals that underpinned our efforts.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

AG: Anyone with even a passing knowledge of contemporary issues in the GCC knows that migration, migrant labor, and human rights are suddenly prominent and heavily researched topics. Very little of that work, however, includes sustained and empathic connections with the migrants in question. As I have already noted, our goal was not to convince the reader of some particular perspective on some particular topic or issue. As a result, we avoided “cherry picking” these narratives for the points and junctures in these migrants’ stories that could illustrate one or the other of the common theses in the Gulf migration literature. Instead, we simply wanted to provide readers with a compellingly written encyclopedia of migrant experiences, and in some small way, to allow a small set of diverse migrants in Qatar to speak for themselves, to reach across the ethnic and class divides that separate us in a place like Qatar, and to allow those migrants to convey their stories and experiences.

J: How does this work connect to and/or depart from your previous research?

AG: In one sense, I wanted to move away from the position of telling my readers how to think about migration in the Gulf. Obviously I have my own opinions, and those opinions are relatively well informed, thanks to the decade of research I have had the opportunity to conduct. But in the college classroom, I have always found it a more effective pedagogical strategy to encourage my students to reach their own conclusions and to think for themselves. In essence, we are trying to do the same in this volume. We’re giving the reader the same raw material that I oftentimes work with myself—migrant stories, experiences, and histories. But it is up to the reader to make sense of these narratives, and to connect the dots that might tell us something about the patterns that characterize the lives of these transnational migrants.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

AG: Our goal with this book was to move beyond the typical academic/scholarly audience. We envisioned the collection possibly reaching peoples in the many different countries from which Gulf migrants come. We envisioned this collection as potentially being of interest to the many members of the transnational professional class that come and go from the various Gulf states. We also thought these migrant narratives might be of use in the classroom, both in the GCC and in other parts of the world.

We were less certain about the collection’s impact. Unlike many academic books, our mission was not to convey to readers a singular, complicated, and nuanced thesis. Instead, we simply wanted to give readers some of the raw material—in this case, migrant narratives—that underpin the production of those theses in other venues. In doing so, we wanted to accurately represent migrant diversity. We consciously included stories of both good and bad migration experiences; we included migrants from a variety of different sending states; we included stories from migrants in both the “regular” sector and in the “domestic” sector of employment in the Gulf; we included narratives and stories from both male and female migrants. That diversity, in all its angles, was important to us.

We also envisioned this collection’s impact in terms of humanizing the labor migrants in Qatar and the GCC. In the analysis of this migration system to which I and others have contributed, it seems to me that many of the problems migrants encounter result from the dehumanizing process that seems to accompany their transnational migration. By portraying labor migrants as humans with agency, as men and women with families and histories, as individuals with experiences, emotions, and feelings, we thought that these narratives might incrementally contribute to improving their collective experience in Qatar and the GCC.

[Images from Constructing Qatar: Migrant Narratives from the Margins of the Global System.]

J: What other projects are you working on now?

AG: Like many of us with a connection to Qatar, the student-researchers and my co-editor are all busy with their own new projects and studies. My own work continues to explore the experiences of the migrant population in Qatar and the GCC. I and several collaborators recently concluded the region’s first large-scale survey of low-income migrants in Qatar, and for the first time we have a quantitative angle on their experiences and problems. I have also been following some of the migrants in Qatar back to the places from which they come, and I have been trying to learn more about the other end of the migration conduits with one endpoint in Qatar.

My new work, however, is focused on urbanism and the urban form in Qatar and the GCC. In part, this interest stems from my interest in labor migrants and their spatial segregation in the city. But that interest has led me in new and unforeseen direction. I am currently working on several different papers on the subject, and I hope to finish preparing a new book on the subject this fall.

J: What was your experience of working on this project specifically as an eBook?

AG: While this book has been available for less than a year, I think our experience also speaks to the viability of the eBook model. The advantages we envisioned for the eBook route were manifold: anyone anywhere with an internet connection could obtain the collection, and we could provide the book at an extremely low cost to encourage its dissemination. Our goal was to ensure that anyone—in Qatar, in Europe, in India, or in any of the other migrant sending states—could access these stories and, potentially, learn something from them.

While we have been pleased (so far) by the success of the book in the Kindle system, I would say that we’re not entirely happy with the trajectory of the collection. Friends and colleagues have reported the difficulty of incorporating eBooks into their course syllabi, for example. Being outside of the academic and scholarly presses to which I am accustomed, we also don’t have a good understanding about how to publicize and market the availability of the collection. And we have no metric by which to measure and understand its dissemination. We are still considering the possibility of publishing the book with a “standard” academic publisher, and to better address some of the goals we envisioned in building this collection, we’re also extremely interested in having the stories and narratives translated into Arabic. For us, the eBook route has been a learning experience.

Excerpts from Constructing Qatar: Migrant Narratives from the Margins of the Global System

Nora Biary, “The Man Who Drives The Bus”

The sweat trickles down his forehead; it’s a typical hot and humid summer day in Doha. Despite the fact that he has spent his entire morning driving hurried passengers to and from the airport in a bus equipped with only the weakest of air conditioners, Raj feels satisfied. At least in the summer the traffic isn’t so bad, which means he doesn’t have to worry about being yelled at by impatient passengers. His phone begins to ring and a picture of his mother appears on the small telephone screen. His mother is a housekeeper in Lebanon. Like him, she escaped from Sri Lanka in order to seek refuge in a place where her identity could be hidden. She tells Raj that one of their neighbors in Sri Lanka, a respected member of the Tamil Tiger rebellion, has just been killed.

As he hangs up the phone, his mood changes to frustration. The heat. His cramped room. The camp boss. His paltry salary. His working hours. In his country he was a leader. He fought for his people; he wanted them to be free. In Doha, he feels far away from that life—too far away to do anything.

Raj was born in a small Tamil village in Sri Lanka. His father was a driver, his mother a housewife. They were a close-knit family, and, being the oldest child, Raj was often left with the responsibility of taking care of his younger brother and sisters. He enjoyed playing the role of caretaker with his siblings and he felt more like a father than a brother. At school, he outperformed the other students, and, after excelling in all his classes, his parents transferred him to a private school in a nearby city where he would attend special nighttime classes. He loved science.

Near the outskirts of the city, the military had imposed a curfew that prevented young single men from roaming the streets. Any young man walking around alone at night could be accused of being a Tamil Tiger—a member of the fierce secessionist movement in northern Sri Lanka. Coming home from his classes late one night, Raj was attacked by several soldiers. They held his arms and forced him into the back of a truck. Inside, four other men were hunched with their hands held tightly to their knees. The five men sat in complete silence. When they arrived at the detention camp, three of the men were lined up and shot in front of Raj’s eyes. He never learned why those three men were killed, why the soldiers were so angry, or why they didn’t shoot him as well. He was too young to understand politics, and he didn’t even know what Tamil Tigers were. He was sixteen at the time, and, sitting in the detention camp, he mostly worried about missing school the next day.

His family reported his disappearance to the police, who claimed they had no idea where he was. Finally, after several months had passed, the police informed his parents that Raj was dead. In reality, he was sitting in a small dark room in a detention camp not twenty kilometers from his grieving parents.

The guards continually dehumanized him. He wasn’t allowed to sleep, and, if he did, the guards would brutally kick him until he was awake. They yelled and barked at him like dogs and kicked him from side to side. His body ached from sitting on the cement floor, and his eyesight weakened from a life in the dark. He spent hours awaiting his only meal of the day: usually a handful of rice. He still marvels at how his body and mind adjusted to his conditions—at first the stench of unchanged clothes and feces in his prison room disgusted him, and he felt overwhelmed by the darkness. But soon enough, his eyes grew accustomed to the dark and his nose accepted the smell.

Every day, the guards gave the prisoners the "privilege" of going out in a small courtyard for five minutes. Raj’s eyes stung whenever the sharp rays of sunlight hit his face. But he spent his days anticipating the brief chance to talk with other detainees. In those five minutes in the courtyard, Raj would look around to see if there were any new prisoners. Every day new people—suspected “Tamil Tigers”—were brought to the detention camp. He began to talk to them.

They taught Raj all about the goals of the Tamil Tigers and their aim to fight for the people of Sri Lanka. The Tigers would not attack civilians. They would only attack the military, who they saw as being “same same as Hitler.” They convinced Raj that the Tamil Tigers would protect his people from the same kind of injustices that the military had committed upon him. Young, intelligent, promising boys would no longer be kidnapped from their families. The more Raj talked to these Tigers, the more determined he became to escape from the camp and join this noble fight for freedom.

Then, one day, something amazing happened. During his five minute recess, Raj realized that he recognized one of the guards supervising him. It was Nasser, the short Muslim boy from his grandfather’s village. Raj was sure that Nasser would help him. Indeed, out of sympathy for his childhood friend and respect for his family, Nasser agreed to help Raj escape. In the deep darkness of a cold night, Nasser unlocked Raj’s prison door, handed him a weapon, and told him to run.

For two hours straight, Raj ran and didn’t stop until he finally reached his home. When he arrived, his parents were shocked. They had spent the last two years convinced that their son was dead. His mother’s hair had grayed, and she seemed much older than he remembered. One of his sisters and his brother were missing; his mother told Raj that they had been shot. Three of her children had been taken away from her in those two years, but she felt lucky because Raj had come back from the dead. It was Nasser who had resurrected him. Years later, while working in Qatar, Raj would learn that the word “Nasser” literally means savior in Arabic.

Raj spent his first ten days at home doing nothing but making up for lost sleep. For six months, he recovered by spending his days sleeping, helping his mother with housework, and eating plate after plate of curry. However, while he relaxed at home, his mother became more and more concerned for her son’s safety. She feared the military would find and punish him for escaping, and she desperately begged him to depart for India.

But Raj didn’t go to India. Instead, he spent five months training with the Tamil Tigers. Immersing himself in leadership training, he learned to use heavy weapons like rockets, mortars, and the AK56. Eventually, he became a leader of a group of fifty young men. As their leader, he collaborated with other Tamil rebels all over Sri Lanka to organize attacks on various military locations. He believed that these would liberate Sri Lanka, and, as long as civilians weren’t harmed, he had no qualms about instigating this violence. One of his proudest moments was the attack he helped lead against a major industrial site in Sri Lanka: casualties were in the hundreds, and the Tigers claimed victory. Raj felt like a hero. He carried cyanide pills in his pocket in case he was caught. He would rather have died than be disloyal to the Tamils and yield information that could hurt them. To him, dying wasn’t a problem. He was one person, and nothing would change if he died. He only wanted his people to be free.

As the years passed and Raj continued to organize attacks, it became unsafe for him to stay in Sri Lanka. He wasn’t afraid of being killed, but he wanted to help the Tamils. He finally gave into his mother’s persistence and escaped to a Tamil refugee camp in India with his mother and sister. It was a large site, and Raj was content. The camp offered him everything he needed to survive: shelter, food, safety, and the company of his family. From India, he continued to organize attacks with Tamil Tigers still in Sri Lanka. He wanted to send the Tamil leaders money, and so he sought out work within the refugee camp. He drove a tractor and painted buildings, earning one hundred rupees (1.50 USD) a day for his labor. After a long day of work, he would reward himself by eating a free meal at the camp’s cafeteria. This was Raj’s life for two years until he received a phone call from his father telling him that India had also become unsafe for the Tamils.

“Qatar,” his father said, “Doha, Qatar. You must go there.” His father explained to Raj that one of their neighbors from the village had moved there several years earlier and could arrange for a work visa. Even India was dangerous for Raj, and it would only be a matter of time before Sri Lankan intelligence would find and prosecute him. Qatar was far away, and he could earn a decent salary there.

Raj agreed to this plan, but his passport was still at home in Sri Lanka. He went to the Sri Lankan embassy in India, asked for an emergency passport, and took a plane to Columbo. He arrived in Colombo’s International Airport early on a hot summer day. He was met by his father, and, in a quick exchange, his father wished him luck and handed him his passport, his ticket, and his entry visa for Qatar. Raj waited in the airport, afraid that, if he walked outside, he would be caught by the state’s intelligence force. Everything had happened so fast. He had arrived at the airport early in the morning. Only a few hours later, he departed for a place he couldn’t even find on a map.

* * *

After a long, exhausting flight, Raj arrived in Doha. His friend met him at the airport and invited Raj to stay with him until he found a job. Most other migrant workers come to Doha for work after signing contracts in their home countries. Raj, on the other hand, was different because he had no pre-arranged job in Doha. After spending several days exploring his options, he decided that he would become a driver. His friend generously loaned him the QR 1,400 (380 USD) he would need to get his license. Finally, after spending a month in idleness, he found a company willing to hire him. The contract seemed fair to him; he was told that he would work eight hours a day and earn QR 1,500 (412 USD) per month. This didn’t seem so bad, and he would be making more money than his friend who was also a driver. He signed a contract written in Arabic. At the time, it didn’t occur to Raj that the conditions written in Arabic on the contract were not the same as those verbally promised to him.

A few months later, Raj lay in bed staring at the ceiling. The air conditioning in his prison-sized room had stopped working a few days earlier, and he could barely breathe. His roommates were too afraid to ask their employer to fix it. Recently, they had asked for the lights to be repaired, and their employer made it clear that he would take the cost of maintenance from their salaries. Clearly, things were not going as well as he had hoped. He was only paid QR 1,200 (330 USD) a month, and to earn that he had to work a ten hour shift—two hours longer and 82 USD less than the verbal promise.

His objections had been futile. Every time he complained about this injustice, his employer retorted that no one had forced him to sign the contract, and that it clearly laid out the working hours and conditions. His employer told Raj that the contract was only a two-year agreement, and, if Raj didn’t like it, he should feel free to leave once the contract expired.

Working long hours, Raj slept only five hours a night; his eyes were perpetually reddened with exhaustion. He had lived before with so little sleep, but now he was tired and his heart and soul were still in Sri Lanka. He had tried to heal the pain of being away from his people by sending about QR 300 (82 USD) of his salary to widows and children in Sri Lanka. Every month, he would collect money with his friends and send it back to charities in their country. This was the most Raj felt he could do. He wanted to send money home this month, but couldn’t because, for the second time, his employer had failed to pay him.

One of Raj’s friends told him about a labor court where workers could go if their employers were abusing or exploiting them. The next morning at work, Raj confronted his employer: if they didn’t pay him the salary he was due, he would take his case to the labor courts.

Today Raj still works for the same company. After his threat, his company no longer forgets to pay him. In fact, his salary was increased to QR 1,400 (385 USD). Although some things have changed, much remains the same. Raj still lives with eight other people in a room smaller than the bus he drives, and he still works ten hours every day. By his own reckoning, his situation is not ideal, but he has learned to cope with being in Qatar by continually reminding himself of the things he loves. He thinks of his family, his mother’s curry, his country, and his people.

[Excerpted from Constructing Qatar: Migrant Narratives from the Margins of the Global System, edited by Andrew Gardner and Autumn Watts, by permission of the editors. Copyright © 2012 by Andrew Gardner and Autumn Watts. For more information, or to purchase this eBook, please click here.]