Critics and reviewers greeted Brian Turner’s Here, Bullet (Alice James Books, 2005) with effusive and unanimous praise. His poems were read as “dispatches from a place more incomprehensible than the moon. . . observations we would never find in a Pentagon press release.” I read the poems back then and was not impressed or moved. I was not surprised that these poems would elicit such praise. Although they were read and were circulating in a climate of timid, but rising opposition to the war (not for the right reasons though) their vision did not challenge or problematize, in any way, the reigning official narrative of and about the war. They did represent the visceral violence of the war, of course, but they never questioned the genealogy of the war itself nor its ideological edifice. What the poems do is humanize the soldier (in a volunteer army) and represent him as a victim, at the expense of civilians (Iraqis). Or, at best, they posit an equivalence between soldiers and civilians. That is quite problematic since being a civilian in a war zone is not voluntary, but being a soldier in the US’s war machine is. Why, then, was the reception so positive and uncritical? In a review of Kevin Power’s Yellow Birds in the LRB last year, Theo Tait highlighted what he termed the “hysterical” reception of that novel and attributed such uncritical readings of veterans’ writings to the fear of sounding unpatriotic. This is quite true, but there is more as this essay will argue.

I had jotted down some notes upon first reading Here, Bullet and planned to write a review, but never did. Almost a year ago I received a kind e-mail from Turner inviting me to submit poems to a special issue of a journal he was guest editing with a focus on war. I did not respond because I was not interested in contributing to this equivalence between warriors and civilians, and between their experiences and representations. Considering the general climate of amnesia when it comes to the Iraq war, I find it quite disturbing and irresponsible that some Iraqi and Arab-American poets and writers participate in such events. The reasons will become apparent in this essay. In that e-mail Turner wrote “Friends of mine in Baghdad tell me that you`ve been highly critical of my work--I respect your stance, if this is so, and I recognize the deep need for this criticism.” I had not written anything critical of Turner in public except for a brief comment on Facebook when a number of Iraqi journalists and poets cheered the news that his collection was being published in Arabic and in Iraq. Some of them wondered why I was being so critical. Was it not necessary to open up to the American other and translate his/her texts? Was I being a censor of sorts in objecting to this translation? Is translation not an important and crucial act that will enrich the target language and its culture?

Having spent considerable time and effort translating literary texts, I consider it of utmost importance and necessity. Translators are free as to their choices and priorities, as are poets. However, the act of translation and the text being translated cannot be detached from their historical and political context. The “other” being translated here was a soldier in an occupying army. These poems were written in the context of a destructive invasion and military occupation and not on a picnic or an exchange-program organized by the State Department. Turner mentioned in an interview with The Washington Post that “Some pages included diagrams drawn also--of ambushes, patrols, things like that.” My critical comments were about the decontextualized manner in which these poems were represented. One question that bothered me was why the rush on the part of an Iraqi to translate poems written by a soldier in an occupying army while we had barely begun to read (in Arabic) about how Iraqi civilians themselves had coped with and were still living the ongoing effects of that horrible war? Sadly, a number of liberal Iraqi writers have internalized the US narrative and still thought that the invading army was there to help birth a democracy, but, alas, Iraq’s culture and history, and Iraqis themselves, aborted the attempt. Iraqis had squandered and abused the “foreigner’s gift.”

What I am interested in is the political and cultural framework in which Turner’s poems are written and read. How is Iraq as a space represented and to what extent does this representation depart from the Pentagon’s narrative of the war which was being reproduced in the cultural mainstream?

What Type of War (Poetry)?

Turner’s poems and other such texts are read as “war poetry” and compared to those written by soldiers in previous wars. There is a distinction that is often overlooked. The draft in the US ended in 1973 and since then the US army has been an all-volunteer force. Class and race overdetermine, to a large extent, the composition of this army and it is often the last or the only opportunity in an increasingly tough economy for many. But this does not change the fact that these soldiers, poets or not, were not forced to join. There are almost a hundred conscientious objectors every year who refuse deployment to war zones. Many have fled or sought political asylum to avoid taking part in wars that have nothing to do with national security and everything to do with imperial hubris and perpetuating the economic and political interests of the elite.

While the great majority of veteran writers join creative writing programs after taking part in the war in order to make sense of their experience and cope with its traumas, Turner’s trajectory is quite unique. He joined the army after getting an MFA in creative writing. In his interviews he cites economic reasons for doing so, but also the desire for a “rite of passage.”

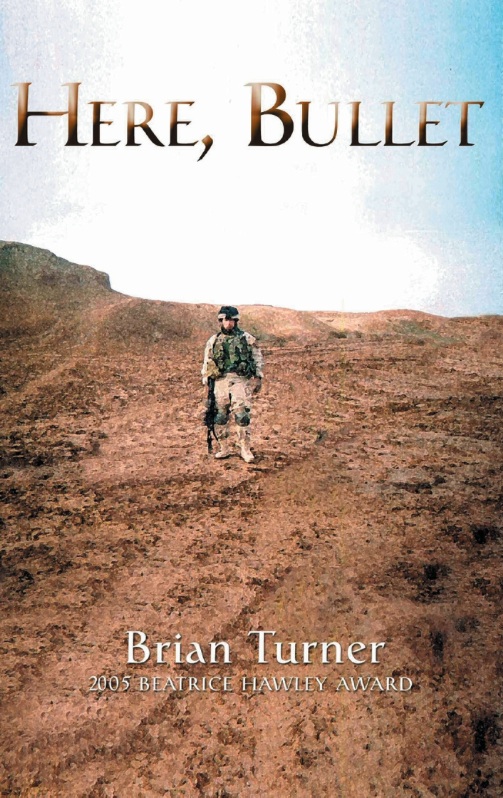

[The cover of Brian Turner`s "Here, Bullet." (Alice James Books) Image by David Jackowski. ]

The Cover

The photograph chosen for the cover and the story behind it are quite telling and crystallize Turner’s problematic approach to his subject. Here is the story in Turner’s own words:

The editor at Alice James Books asked me to send along a number of photos . . . She came across one photo and said “this has got to be the cover”, but it was very contentious for me for several reasons. . .Behind me and to my left there was our Stryker, our vehicle, and it was in the photo. It was facing away from us and its ramp was down, and from the photo you could see inside the back. There was stuff inside that might be considered classified or secret, so it was just easier to take it out. The contentious part of the photo—and I struggled with this—on the cover just above my name in the lower half of the photo, between the photographer and me were three Iraqi prisoners. They were on their knees, their hands were flexcuffed behind their backs, and they had sandbags over their heads. Jackowski, he was my M203 gunner, he took the photo. The prisoner on Jackowski’s right had a leather jacket on and we’d written RPG across his back because he’d fired a Rocket Propelled Grenade. In fact, Jackowski was in the center of a circle of prisoners—about ten or thirteen of them—and the stance that I have in that photo looks sort of like John Wayne. That photo looks like “I came over here to chew bubblegum and kick ass, and I’m all out of bubblegum,” as they say in the movies. It just wasn’t right for a cover photo, especially with the sandbags over the heads because that’s now synonymous with torture. If I were someone walking into a bookstore—as we were talking about this during the editing process—I felt like some people would be repelled by that image. They would just think torture right off the bat, and this book isn’t about torture. There are books that need to be written about torture, and some of those are starting to come out, but my book isn’t about that. I wanted to invite people into the book rather than push them away.

What is striking is how any reference to or reminder of the torture practiced by the US in Iraq should be displaced outside the actual and discursive frame. A distance between the act and those perpetrating it or the institution itself is created. Thus, torture, in effect, becomes an exception (the official narrative: a few bad apples) and not a normal practice. The “flexcuffed” Iraqis whose heads are covered with sandbags and whose fate remains unknown to us, disappear (thanks to Photoshop). The military vehicle into which the Iraqis were hurled disappears as well. What remains is the lone American soldier amid the harsh landscape. The result is a perfect fit for national mythology. A white man taming nature to establish or extend civilization. The natives are conveniently absent. They could have been details in or part of the landscape, but the sandbags would have tarnished the image.

A Clash of Civilizations

The opening poem in the collection is “A Soldier’s Arabic.” It reproduces one of the classical themes in the Orientalist archive. The other’s language is not a system that can be understood or decoded or translated, but an unfathomable object that reflects an essential difference:

The word for love, habib, is written from right/ to left, starting where we would end it/ and ending where we might begin./Where we would end a war/another might take as a beginning,/or as an echo of history, recited again./ Speak the word for death, maut, /and you will hear the cursives of the wind/driven into the veil of the unknown./This is a language made of blood/It is made of sand, and time./To be spoken, it must be earned.

War here is a cultural and civilizational clash. This discourse calls for the usual signifiers: “veil” and “unknown.” “Habib” is actually ”lover” and not “love.” It is no surprise that the second poem in the collection is about the Baghdad zoo and the traumatic situation of its animals. The story had garnered significant attention at the time. Animals always fare much better than humans when competing for empathy in the civilized world. The endnotes mention that the poem was inspired by the great efforts to save the animals.

The following poem (“Hwy 1”) (p. 6) takes its title from the highway stretching from Umm Qasr in the south all the way to Baghdad and then westward to Jordan and Syria. The poem begins with “The Highway of Death,” which is the stretch from Kuwait to Iraq. It acquired this name after the US bombed retreating Iraqi troops from Kuwait in 1991, killing and charring thousands of them. None of this crucial information appears in the notes at the end. The first section imagines the ghosts of the Iraqi dead returning to their homes, but we are soon taken to its imagined past as a road for all types of exotic commodities passing through. The third section narrates passing by Marsh Arabs and the ruins of Babylon and Sumer and the land of Gilgamesh. History overwhelms geography and its images overrun real humans on the ground (we do have waving children though). The poem ends with a Crane being shot.

Iraqi civilians and their suffering do appear en passant. There is a poem about Halabcha. And in “Night in Blue” (p. 64) we read: “I never dug the graves in Talafar./I never held the mother crying in Ramadi./I never lifted my friend’s body/when they carried him home.” In “Sadiq” (Friend) (p. 56) the poet writes “it should break your heart to kill.” It is not obvious who the addressee (the killer) is? An American soldier or an insurgent? The latter is an important figure in Turner’s poems. We read on p. 8: “Black marketer or insurgent-/an American death puts food on the table,/more cash than most men earn in an entire year.”

The identity of the addressee is important in this context because of the confusion/conflation of, or equivalence, conscious or not, between civilians and soldiers (Iraqis and Americans). In “Ashbah” (Ghosts) we read: “The ghosts of American soldiers/wander the streets of Balad by night,/. . . And the Iraqi dead,/they watch in silence from rooftops.” This is consonant with the reigning narrative in which both Iraqi civilians and American soldiers become victims of this war and those who launched it and carried it out vanish! Those who kill and those who are killed are equal in terms of victimhood.

Many of the poems read as if they are military reports or poetic translations of the smart cards distributed by the Army to reduce Iraq, Iraqis, and their culture to racist stereotypes. Take, for example, “What Every Soldier Should Know” (pp. 9-10):

If you hear gunfire on a Thursday afternoon/it could be for a wedding, or it could be for you/Always enter a home with your right foot:/the left is for cemeteries and unclean places/O-guf! Tara armeek is rarely useful/It means Stop! Or I’ll shoot/Sabah el khair is effective/It means Good morning/Inshallah means Allah be willing/Listen well when it is spoken/You will hear the RPG coming for you/Not so the roadside bomb/There are bombs under the overpass/in trash piles, in bricks, in cars/There are shopping carts with clothes soaked/in foogas, a sticky gel of homemade napalm/Parachute bombs and artillery shells/sewn into the carcasses of dead farm animals/Graffiti sprayed onto the overpasses/I will kell you, American/Men wearing vests rigged with explosives/walk up, raise their arms and say Inshallah/There are men who earn eighty dollars/to attack you, five thousand to kill/Small children who will play with you/old men with their talk, women who offer chai-/and any one of them/may dance over your body tomorrow.

The last few lines are stunning. No matter how kind or humane they may appear to be, any civilian, child, woman, or old man, is potentially a barbarian who “may dance over your body tomorrow.” There is no Iraqi who does not cause, encourage, or celebrate death. It is not surprising then that Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker (2008) took its title from one of Turner’s poems. The film represented Iraqis either as terrorists or potential terrorists, whereas the American soldier is the victim with whose perspective the viewer identifies. Although the film parrots the official narrative (we went to help them, but are trapped there) and never question’s the war’s genealogy or its legitimacy, it was hailed as an anti-war film. In an Orwellian, permanently militarized society, a pro-war text can easily be read by the mainstream as its antithesis. “Uncritical support of all things martial is quickly becoming the new normal. . . That which is left unexamined eventually becomes invisible.”

Embedded Poetry

“Observation Post,” is the title of two poems (followed by the number of the post) and it could very well serve as a metaphor for the poetic discourse in this collection. This is poetry that sees Iraq through military binoculars and “whatever spreads before him is a battlefield” to quote Saadi Youssef. Turner called himself an “embedded poet” in an interview. The genealogy of the concept and its political deployment is well-known. It is hardly positive unless one intends to reproduce the war’s official discourse, just as the corporate media has been doing so well in the last few decades, but especially after 2003.

Turner returned to Iraq in late 2010 as a civilian to write an article for National Geographic. One would expect a more critical and nuanced view, but “Baghdad After The Storm” is naïve and touristic. Turner writes about the Mongol invasion and destruction of Baghdad in 1258 and then jumps to the civil war of 2005-2007. There is no recognition whatsoever of the destructive damage brought about by the occupation army Turner was part of. The article ends on a naïvely optimistic note and sounds like one of the media’s happy stories about post-occupation Iraq:

I can see more clearly now that Baghdad is becoming a new version of itself—not a place defined by war . . . but a more livable, thriving place. Although it will certainly take time, and the aftermath of war will leave an indelible signature here for the rest of our lives, Baghdad has begun to reimagine itself as a majestic city once more.

These words were written at a time when the catastrophic effects of the occupation and of the policies of the corrupt political system it installed were tangible everywhere in Iraq. Here, Bullet is embedded poetry par excellence. It views Iraq and Iraqis from an observation post and through military binoculars. And whatever it sees is filtered through a version of the war’s official narrative. The occupier is a victim trapped in a foreign landscape, fighting a war in an incomprehensible place (“more incomprehensible than the moon according to the NYT review).

The war in Iraq is over. "We" tried to help those wretched Iraqis, but it was all just too messy (Sunnis, Shi`ites, Iran. . . etc). "Mistakes were made" along the way. Iraqis will have to fend for themselves. This narrative, with a few variations, is parroted by the mainstream chorus. It obfuscates the tragic reality that is Iraq and absolves the authors of the war of any responsibility.

The civilian victims are disappeared.

The soldiers are the victims.

Did the war wage itself?

[This article was originally written in Arabic and published on Jadaliyya. It is translated by the author.]

![[Hooded Iraqi prisoner comforting his son. Image by Jean-Marc Bouju from pdnonline.com]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/hodded.jpg)