Part 1: Why Fanon? The Indispensability of Thought and the Urgency of Action

Palestine is in the throes of revolt. It started with protests and demonstrations at the presence of Israeli “Temple Mount” activists (and their political benefactors) at the Noble Sanctuary of Al-Aqsa in Jerusalem, the symbolic pillar of Palestinian spirituality and national redemption. The unrest then spread to other cities on both sides of the Green Line. From Nazareth to Nablus to Bethlehem, young Palestinians have taken to the streets to hurl stones and Molotov cocktails at an occupation that plunders their future and consigns their bodies to be broken on the wheels of a colonial machine. Individual acts of violence have also injected a sense of terror into the Israeli population, prompting a paranoid state to respond with unbridled brutality from its military, and unabated mob-driven lynching by its civilian population.

Unorganized, sporadic, and youth-led, these Palestinian demonstrations and violent attacks do not appear to be tethered to any political party. The rejection of political factions as the incubator of rebellious actions by the “Children of Oslo” is perhaps the final indictment on the political malaise that has characterized Mahmoud Abbas’s tenure as Palestinian president; he has operated hand in glove with the Israelis, to protect a regime that safeguards the interests of his political class.

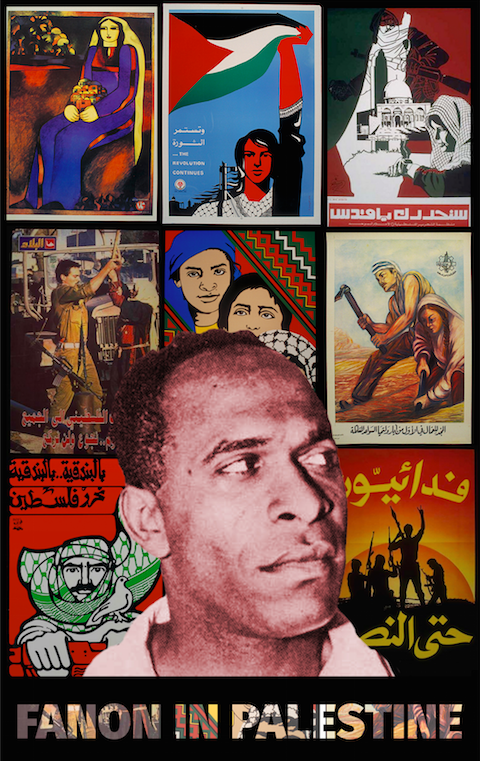

The “Question of Palestine,” as Edward Said framed it, has gone through numerous changes since 1948; through the Nakba of 1948 to the concept of sumud, which characterized the first intifada, to the compromise of Oslo and the current post-second intifada division and status quo. Throughout these phases, various normative discourses and institutions arose, which shifted the nature of the Palestinian national movement. However, the reality of Israeli colonialism has remained the same: violent, intransigent, and unaccountable. In order to understand the current events in Palestine properly, it is vital to look toward the writings of Martinican psychologist-cum-Algerian revolutionary, Frantz Fanon, whose divisive thoughts have contributed prodigiously to the field of postcolonial studies.

Rebel Without a Pause

1925 was a bumper year for black revolutionaries. In the space of twelve months, Malcolm X, Patrice Lumumba, and Frantz Fanon were born. It was the latter’s lyrical polemics and psychoanalytic inquiries which presented vast swathes of humanity with the framework for picking apart the layers of oppression that typified their lives under the yoke of colonialism. In his short life, Fanon developed a philosophy that provided colonized peoples with the blueprint for breaking out of their stupor, to create a “new man” and a new form of resistance to domination and oppression. Added to his literary panache and intellectual intrigue, he was able to interweave his subjective experiences into his works. By the time of his untimely death at thirty-six, Fanon had first-hand experiences of colonial society in a variety of contexts: through his youth in the French colonial department of Martinique; his service for “Mother France” on the battlefield against Nazi Germany; his academic training in France’s metropoles; and his works with Algerian revolutionaries in the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN).

Black Skin, White Masks

In Black Skin, White Masks Fanon developed a sociogenic and psychoanalytic explanation of the anti-black racism inherent within colonial societies, drawing on his objective experiences. In this seminal text, Fanon passes the Hegelian phenomenological master/slave dialectic under a black lens. In Hegel’s dialectic, the slave is in pursuit of recognition and, through fear of the master, develops sentience, acquiring independent thought and consciousness of his essentiality and master’s dependence on him. However, when the slave is black, Fanon notes that, “What [the master] wants from the slave is not recognition but work.” The result was for the black person to aspire for “values secreted by his masters.” Fanon stays with Hegel when he acknowledges that mutual recognition is not achieved at the end of this dialectic, yet departs from him in denying that the black slave necessarily achieves any independent consciousness: “But the black man does not know the price of freedom because he has never fought for it.” Echoing the words of Malcolm X, he wrote, “No one can give you freedom, if you are a man, you take it.” This ongoing struggle for recognition and freedom informed Fanon’s work and life.

Revolutionary Therapy and the Process of Disalienation

In 1953 Fanon moved from colonial France to Blida, Algeria, where he developed a revolutionary approach to psychoanalysis, developing occupational therapy remedies with Algeria’s native communities with a direct effort to draw Arab and Islamic idiosyncrasies into his work. Fanon published fifteen papers on psychiatric approaches throughout his career, and many of the findings were intertwined with his philosophical conclusions in Black Skin, White Masks. At the center of Fanon’s psychoanalysis and “sociogenic” inquiries was a pursuit of disalienation from the social death caused by colonialism. In Marx’s Capital, alienation from labor is scrutinized, and through this process he lays bare the opposite of humanity within a capitalist society: a society freed from capital, able to pursue its own praxis. Fanon examined the way in which the human society under colonialism is alienated from its own cultural creativity; from this he wanted to create a way of breaking out of the colonial replications of that which is colonized. For Fanon, the colonized must pursue this process of disalienation actively.

Concerning Revolutionary Violence and the Pitfalls of Neocolonialism

During his time in Algeria, the FLN approached Fanon to provide healthcare and a sanctum for their fighters in his clinic. He subsequently threw his weight behind their cause, writing for their publication El Moujahed and representing them at conferences in sub-Saharan Africa, where he forged ties with Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah and the Congo’s Patrice Lumumba. With them he developed the idea of an African Legion, to liberate African nations from colonialism, as well as opening up a southern arms route from sub-Saharan Africa to Algeria. Fanon saw that the conclusion of the Algerian struggle would serve as the pacesetter for the trajectory of the postcolonial movements and newly liberated nations throughout Africa.

With the publication of A Dying Colonialism he had moved considerably from the concept of negritude, toward revolution as the prime negative in his de-colonial framework. By the colonized finding themselves through revolutionary struggle, while at the same time realizing the role played by national demands and racial particularities, a new humanity can be forged.

In 1962, Fanon was diagnosed with leukemia, and started work on The Wretched of the Earth, which was to be completed within months of his diagnosis but only published posthumously. Written with furious energy, the text is as much a timeless field manual for postcolonial movements as it is a piece of historical literature. It is his treatise on violence which has often been misconstrued, by supporters and detractors alike. Fanon does not valorize violence, as some contend, but rather acknowledges that colonialism is a project, which is, in and of itself, violence manifested. This violence has shaped the social constitution of the colonial subject. His land, resources, and life have been seized by a state of violence, and within the framework laid before him the only route out is violence. With prescience, Fanon writes that unless this violence is checked, it can turn inward on the colonized, leading to tribalism and internecine conflict. Out from this a neocolonial project will emerge, where elites from the revolutionary movements will barter their political capital with the old colonialists, for political power and capital, granting the latter rapacious access to resources and economic wealth.

Before he died in 1963, Fanon sent a parting letter to his friend Roger Taïeb in which he wrote the following:

We are nothing on this earth if we do not first and foremost serve a cause, the cause of the people, the cause of freedom and justice. I want you to know that even when the doctors had lost all hope, I was still thinking, in a fog granted, but thinking nonetheless, of the Algerian people, of the people of the Third World, and if I managed to hold on, it was because of them.

Israel’s Occupation as a Neocolonial Project

What Fanon implored us to do was to view the struggle of the oppressed as a struggle to create a new mode of being, a new form of humanity. Within the revolutionary struggles of the masses, he insisted, lie the seeds of a new humanity. The ongoing resistance in Palestine today is not a new phenomenon, but is rather the latest episode in a decades-long struggle for freedom and what Hegel and Fanon both agree on—recognition. Not recognition to live within shrivelled little cantons and drip-fed subsistence, but recognition as a human being in the holistic sense of the term. The stone throwing, the stabbings, and the bombings are a reaction to a colonial regime that denies this recognition.

Over the course of these essays, Fanon’s key works, as outlined briefly above, will be utilized to examine the Palestinian national movement since it broke away from the paternalist hold of the Arab world and began, in earnest, to seek recognition. Navigating this history, with one eye firmly on Fanon’s work, it will conclude with where the movement is today: largely rudderless, but still yearning. Through this process, it is hoped that the reader will not only think and empathize with the Palestinians, but also, in respect of Fanon’s work, act on these feelings in the spirit of a collective humanity.

[This article was originally published in Middle East Monitor.]