The Syrian Center for Policy Research, Forced Dispersion: A Demographic Report on Human Status in Syria (Beirut: Tadween Publishing, 2018).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

Rabie Nasser (RN): The Syrian Center for Policy Research (SCPR), an independent and non-profit research center, seeks to study and diagnose the socioeconomic roots and impact of the conflict in Syria. The research team worked to build a comprehensive framework to analyze the institutional, social, economic, and environmental status of the country and its people during the conflict; we called the new framework the Human Status of Syrian people. One essential pillar of the framework is the demographic dynamics—factors like mortality, fertility, and migration of the population. As the conflict caused severe impacts in terms of increasing conflict related deaths and wounded people, distortion in fertility patterns, and aggravation of forced displacement inside and outside the country, the team chose to conduct a national survey to build the analysis on hard evidence and to understand the dynamics of demographic distortions. Based on said analysis, the book provided policy alternatives to counter the demographic consequences of the Syrian catastrophe.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

RN: The book revisited the demographic transition in Syria before the conflict and produced new evidences on population growth, mortality, fertility, and migration. The results show that the last decade (2000-2010) witnessed some adverse results; the average annual population growth rate of the Syrian residents reached 2.9 percent for the period spanning from 2004-2010 (compared to 2.45 percent according to the official estimations), which reflects an increase in the fertility rate. The pre-conflict analysis also shows an increase in mortality rate between the years 2007-2010, which profoundly reflects increasing deprivation of appropriate health services and living conditions. Additionally, the lifetables of Syria that have been built for this book show that the life expectancy at birth in the official estimations (including the WHO ones) are overestimated and do not capture the reduction in life expectancy between the years 2007-2010. These adverse shifts indicate the failure of population-related programs and policies that targeted reducing population growth rates, and it provides additional proof of the inefficiency of family planning programs in isolation from inclusive development.

During the conflict, the team conducted a non-traditional survey to capture the demographic transition. This survey revealed many indicators: first, the crude mortality rate increased from 4.4 per thousand in 2010 to 10.8 per thousand in 2015, accounting for the indirect and direct deaths of about 1.9 percent of the total population. As a result, the life expectancy declined significantly for males a from 69.7 in 2010 to 48.4 in 2015, and to a lesser extent for females, from 72 years in 2010 to 65 years in 2015. Second, it estimated the total population inside Syria, which was 20.2 million people in 2015, about 31 percent of whom were displaced, along with 4.1 million refugees and migrants. Consequently, the portion of the population that had not moved was about 57 percent of the total population inside and outside Syria. Third, the crude birth rate witnessed a notable decrease, from 38.8 per thousand in 2010 to 28.5 per thousand in 2014, which reflected a decline in total fertility rate to 3.7 in 2014. These results contradict many perceptions about increased fertility rates during conflict, particularly among displaced people. The lack of security, the deterioration of living conditions, and the general sense of instability accompanied by family fragmentation imposed by the conflict have led to the spread of early marriages and the exploitation of children and women’s rights.

The book provides a critical assessment of the population policies and counters the narrative that assumed that high population growth is the core root of the conflict. This narrative neglects the role of political oppression and role of neoliberal policies, which ultimately failed to achieve inclusive growth and human security. The book suggests priorities for population policies to halt the conflict and overcome its impacts. In this context, dramatic changes in population policies should be adopted toward priorities of stopping the killing, guaranteeing the right to life, decomposing the economics of violence, and facing the challenges of forced internal and external migration to regain people and social cohesion. The main issue during the conflict is to build population policies within effective and participatory institutions that take into account developmental and humanitarian dimensions in preparing, implementing, and monitoring phases of any policy. Moreover, changes of the actors’ roles should be taken into account in building new institutions and contributing to future population policies. These actors include the state, emerged local powers, civil society, private sector, and the international community.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

RN: As SCPR attempts to understand the development paradigm in Syria, it recognizes the importance of the demographic transition as a key pillar of this paradigm. Furthermore, the mainstream analysis has been trapped in the family planning programs; therefore, SCPR chose to build a research project that reassess the demographic transition in Syria before and during the conflict. The results clarified many important aspects that helped in assessing the developmental performance in Syria, like the failure in decreasing the fertility and morality rates during the intensive implementation of neoliberal policies. Moreover, it gives the team a comprehensive understanding of the conflict consequences on the population characteristics in terms of forced dispersion, gender and age distortion, conflict related mortality and morbidity, and human development. This work creates many questions that need to be addressed, like the role of different policies—conducted by different actors—on the demographic transitions. Many questions about the role of brutal military attacks, killing, kidnapping, looting, rape, and besieging on the population status in Syria need to be addressed in the future research agendas. Finally, this work will be part of the background work that will help in designing the alternatives policies for Syria in the future.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

RN: Our expected audience is members of the research and academic community, policy makers, civil society, United Nation agencies, and journalists. We hope that this humble effort will clarify some of the demographic aspects that could help us to better understand the conflict dynamics and also help in providing evidence to support more effective interventions from the population status point of view. Finally, we hope that this effort could help in establishing a more effective dialogue on demographic policies for the future of Syria.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

RN: Our main project that we are working on, with the participation of many researchers and experts, is the Alternative Development Paradigm for Syria, which aims to build a constructive evidence-based dialogue on the future of Syria to counter the conflict and fragmentation and converge toward inclusive development path. Additionally, we are working on studying the impact of the conflict on the socioeconomic situation in Syria during 2016-2017, focusing specifically on conflict-economy dynamics, food security, public health during conflict, and institutional dynamics.

J: What are the main debates that have been created around the results of the book?

RN: The first debate is about the official estimations of population growth fertility and mortality; this book exposes the official underestimation of deaths, births, and population growth. The second debate revolves around the role of population growth and youth bulge; this book counters the narrative that suggested that this was a core root of the conflict. Seeing as the same phenomena were a reason for sustainable development in East Asia, we brought the discussion back to the roles of institutional bottleneck, mainly the political oppression, and the neoliberal policies and the flourish of crony capitalism in creating the conflict environment and then fueling it. Furthermore, the conflict results countered mainstream narratives that assumed that conflict leads to an increase of fertility among displaced people; our evidence shows the opposite, that the fertility rate dropped substantially. Another debate was on the population number and life expectancy estimations among other discussions. We believe that these debates are very important steps to build new conceptual and policy oriented frameworks that help us in understanding the roots and consequences of conflict in Syria and other similar countries. This could ultimately help to adjust developmental policies to an effort to prevent or counter the conflict and instability.

Excerpt from the Book:

Toward Participatory Population Policies

Syria is subject to one of the largest humanitarian crisis disasters after the WWII. Its roots are political oppression, subordination, exclusion, and suppression, in addition to a widening gap between the formal institutions and the society’s needs and aspirations, as these institutions have become neo-patrimonial entities motivated by loyalties and royalties. The social movement in Syria erupted to substantially change the structure of these institutions, intending thereby to ensure rights and public freedoms. The subjugating powers, including political oppression, fundamentalism, and fanaticism supported by external powers, have diffused the movement and led to nihilist armed conflict that has killed, injured, or disabled hundreds of thousands of people. At the same time, many people have been subject to kidnapping, detention, and torture, which have pushed millions to leave their places of origin and flee to other places inside and outside Syria. This migration has resulted in radical changes in demographic indicators in Syria and dramatic shifts in the population map. Therefore, it is crucially important to build population policies in the short term, taking into account the immediate population needs while developing strategies for sustainable inclusive development.

During the first decade of the millennium, attention to population status increased in Syria through several procedures and pieces of legislation that focused on the reduction of fertility rates using family planning programs. Thus, the government aimed to control the relatively high population growth that was seen as an obstacle to economic growth and sustainable development. This approach accompanied an absence of deep institutional reform, poor coordination between the concerned parties working on the demographic status, and a lack of effective monitoring and evaluation systems. Consequently, there was little efficiency and much confusion in the application of population-related policies, decisions, and actions. In this context, the demographic pre- crisis indicators show relative deterioration in deaths and fertility. Formal institutions were obstacles to the development, creating major distortions in terms of efficiency, transparency, and accountability. These institutions failed to integrate the population issue within an inclusive development framework, neglecting the population issue in public policy and instead, in many cases, dealing with it from the purely demographic perspective, adopting approaches close to the neo-Malthusian perspective.

During the crisis, the developmental and institutional deterioration has deepened significantly and unprecedentedly, and all resources and potential have been reallocated to serve violence and subjugating powers. Population policies have thus been largely neglected focused mostly on food and medical aid distribution, raising awareness, and training courses without any evaluation of the courses’ relevance to, or impact on, society. A more dangerous concern is that the provision of medical services, food assistance, and aid has been exploited as a tool in the conflict in favor of the warring parties. Overcoming the impacts of the crisis requires genuine and effective participation of all social powers, informed by future vision and using all available capacities; a lack of participatory involvement will impede the success and the sustainability of any future project.

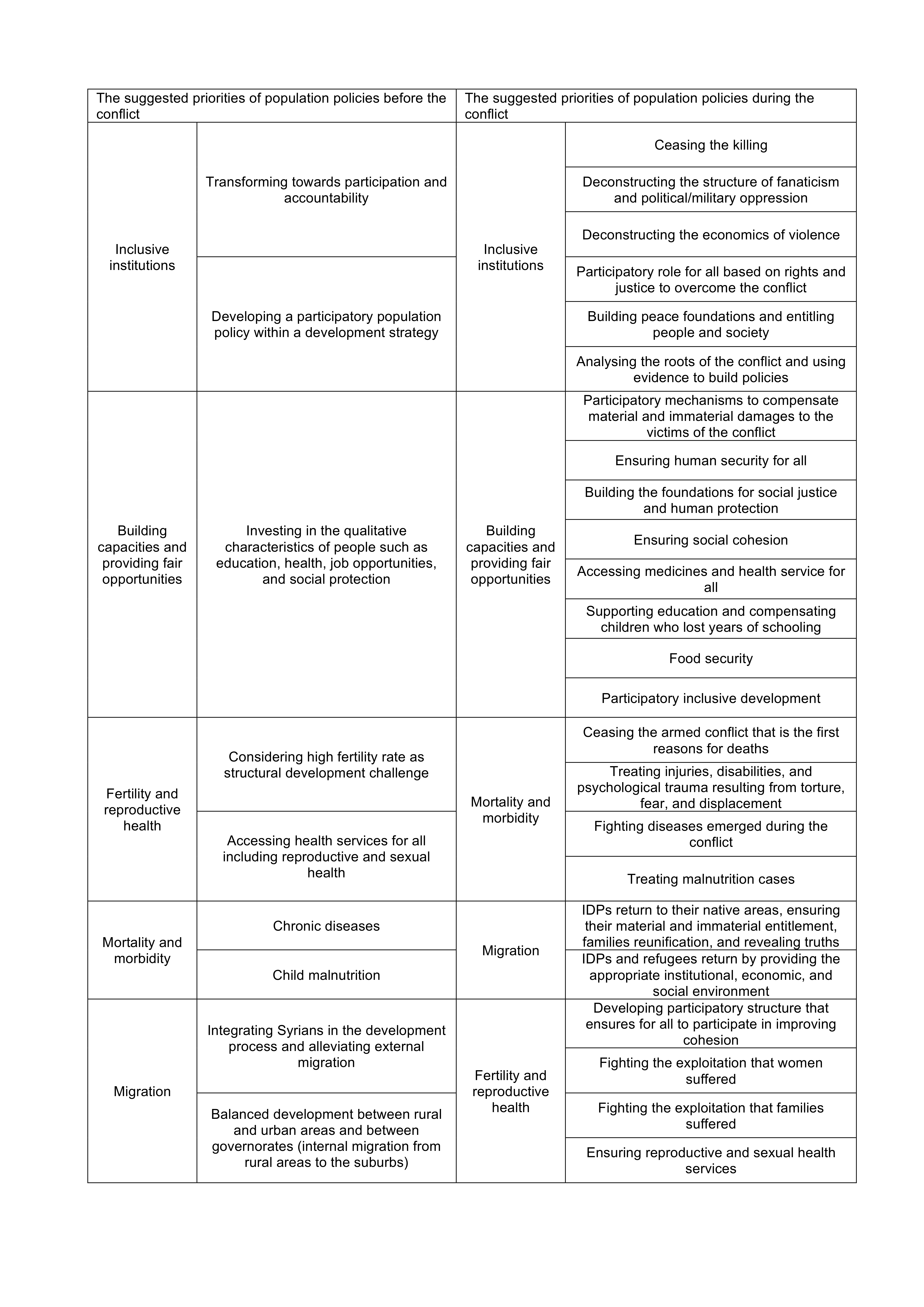

In this context, and given the results from the research process in finalizing this report, priorities for population policies have been suggested in a framework of halting the conflict and overcoming its impacts. These priorities were compared with suggestions related to population policies before the crisis. In this context, huge changes in population policies could be noted, as the suggested priorities changed from institutional transformation towards better investment in people’s capacities and a reduction in the fertility rate through a participatory development paradigm; also toward priorities of stopping the killing, guaranteeing the right to life, deconstructing the economics of violence, and facing the challenges of forced internal and external migrations to regain people and reestablish society. The main issue during the conflict is to build population policies within effective and participatory institutions that take into account developmental and humanitarian dimensions in preparing, implementing, and monitoring phases of any policy. Moreover, changes of the actors’ roles should be taken into account in building new institutions and contributing to future population policies. These actors include the state, emerged local powers, civil society, the private sector, and the international community.

Change between the suggested priorities of population policies before and during the conflict: