Government-Compiled Dossier Accuses Organization of Promoting Boycotts

(Jerusalem) – Israeli authorities on May 7, 2018, revoked the work permit for Omar Shakir, the Human Rights Watch Israel and Palestine director, and ordered him to leave Israel within 14 days, Human Rights Watch said today. The government said it was because of Shakir’s alleged support for boycotts of Israel.

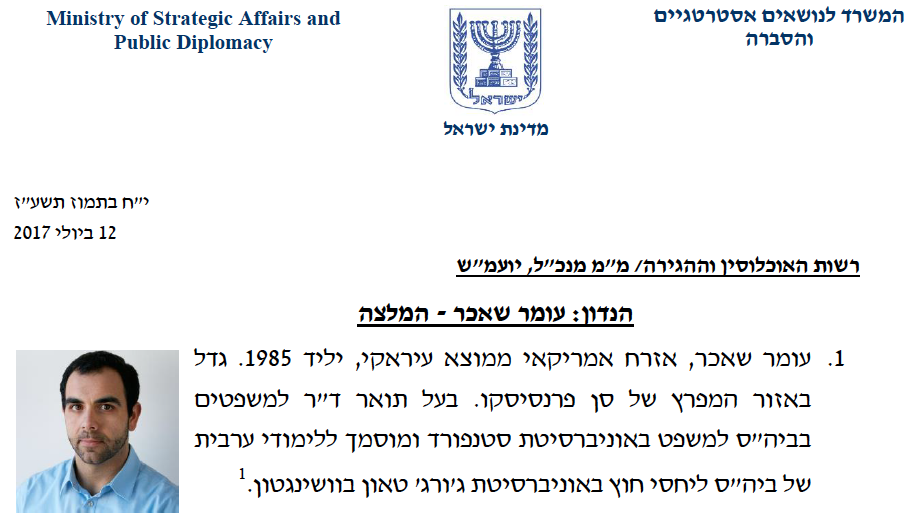

A dossier compiled by Israel’s Strategic Affairs and Public Diplomacy Ministry on the activities of Omar Shakir, Human Rights Watch’s Israel and Palestine Director, which served as the basis for the government’s May 7, 2018 decision to revoke his work visa.

Authorities based the decision on a dossier a government ministry compiled on Shakir’s activities spanning over a decade, almost all of them predating his Human Rights Watch employment. The decision comes a year after the Interior Ministry granted Human Rights Watch a permit to employ Shakir as a foreign expert, after initially refusing to issue it.

“This is not about Shakir, but rather about muzzling Human Rights Watch and shutting down criticism of Israel’s rights record,” said Iain Levine, deputy executive director for program at Human Rights Watch. “Compiling dossiers on and deporting human rights defenders is a page out of the Russian or Egyptian security services’ playbook.”

A dossier compiled by Israel’s Strategic Affairs and Public Diplomacy Ministry on the activities of Omar Shakir, Human Rights Watch’s Israel and Palestine Director, which served as the basis for the government’s May 7, 2018 decision to revoke his work visa.

A dossier compiled by Israel’s Strategic Affairs and Public Diplomacy Ministry on the activities of Omar Shakir, Human Rights Watch’s Israel and Palestine Director, which served as the basis for the government’s May 7, 2018 decision to revoke his work visa.

Israeli authorities should reverse the decision, Human Rights Watch said. Human Rights Watch stands fully behind Shakir and has retained counsel to challenge the decision before an Israeli court.

The May 7 letter notes that the decision “does not constitute a principled or sweeping refusal for the organization to employ a foreign expert,” but rather relates specifically to Shakir. However, a February 2017 Interior Ministry decision to deny a work permit did target the organization, saying that its “public activities and reports have engaged in politics in the service of Palestinian propaganda, while falsely raising the banner of ‘human rights.’” The ministry later reversed course, granting Human Rights Watch a permit in March 2017 and issuing Shakir a one-year work visa on April 26, 2017.

In 2011, Israeli authorities passed a law allowing people to file lawsuits and seek damages against anyone who publicly calls for boycotts of Israel, defined to include boycotts of settlements. In March 2017, an amendment to the Law of Entry, cited in the May 7 letter, empowered authorities to refuse entry into the country to activists who publicly call for or have committed to participate in a boycott against Israel.

On November 16, 2017, the Interior Ministry notified Human Rights Watch that, based on a private lawsuit filed in a district court in Jerusalem challenging the work permit, it had initiated a review of Shakir’s status in Israel. In December, the Strategic Affairs and Public Diplomacy Ministry furnished a dossier “on Shakir’s activities in the boycott field over the years.” It included a recommendation, endorsed by the strategic affairs and public diplomacy minister, Gilad Erdan, that “Shakir should be stripped of his work visa and denied re-entry into the country.”

Human Rights Watch applied in January 2018 to extend Shakir’s work visa, which was due to expire on March 31. On March 29, the Interior Ministry extended the visa for a month pending a decision on revocation.

Neither Human Rights Watch nor its representative, Shakir, promote boycotts of Israel, as Human Rights Watch noted in its reply to the Interior Ministry. The Interior Ministry acknowledged in its May 7 letter that “no information has surfaced regarding such (boycott) activities” since Shakir joined Human Rights Watch. Human Rights Watch has found that businesses operating in settlements inherently benefit from and contribute to serious violations of international humanitarian law and, on that basis and as part of its global efforts to urge companies to meet their human rights responsibilities, has called for companies to cease operations in settlements. Human Rights Watch also defends individuals’ right to express their views through nonviolent means, including participating in boycotts.

Israel’s Strategic Affairs Ministry, created in 2006, has dedicated significant resources to monitoring critics of Israeli policy. On April 29, Israeli authorities denied entry to the American human rights lawyers Vincent Warren, executive director of the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR), and Katherine Franke, chair of CCR’s board and a Columbia University professor. Israeli officials have accused Israeli advocacy groups of “slander” and of discrediting the state or army, and, based on a law adopted in 2016, have required from them extensive financial reporting that burdens their advocacy. Palestinian rights defenders have received anonymous death threats and have been subject to travel restrictions and even arrest and criminal charges.

Human Rights Watch is an independent, international, nongovernmental organization that promotes respect for human rights and international law. It monitors rights violations in more than 90 counties across the world, including all 19 countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Headquartered in New York City, Human Rights Watch has registered offices in 24 countries around the world, including Lebanon, Jordan, and Tunisia. Human Rights Watch shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1997 as a founding member of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines.

To accomplish its mission, Human Rights Watch relies on professional researchers on the ground and regular engagement with government officials as well as with others with first-hand information. Human Rights Watch maintains direct access to the vast majority of countries it reports on. Cuba, North Korea, Sudan, Iran, and Venezuela are among the handful of countries that have blocked access for Human Rights Watch staff members. Human Rights Watch has for nearly three decades had regular access without impediment to Israel and the West Bank – though not Gaza, to which Israel has refused access to Human Rights Watch’s researchers and other senior officials since 2008 except for a single visit in 2016.

As part of its mandate, Human Rights Watch conducts research and advocacy that exposes and challenges violations of all actors in the region, including the Palestinian Authority and the Hamas authorities in Gaza. In 2017, in addition to documenting abuses related to the occupation, Human Rights Watch reviewed Israel’s record on women's rights and reported on the incommunicado detention of Israeli citizens Avera Mangistu and Hisham al-Sayed by Hamas, and criticized the Palestinian Authority’s draconian cybercrime law that restricts free expression.

“This is the first time since Human Rights Watch began monitoring Israel and the Occupied Territories 30 years ago that Israel has ordered one of its staff out of the country,” Levine said. “But it’s only the latest among many recent examples of Israel’s growing intolerance of those who criticize its human rights record.”

[This report was published by Human Rights Watch.]