“The Palestinian people today face problems of formidable proportions.”

—Excerpt from a 1976 study

The State of Palestine, even while under prolonged Israeli military occupation, has potential. Traditional industries have been identified by numerous reports as key pillars to any current or future Palestinian economy: agriculture, building materials, construction, information and communication technology (ICT), light manufacturing, and tourism. As productive sectors, these are all poised to uplift Palestine’s economy, some more than others while Israel still micro-manages all of Palestine’s strategic economic resources. However, one sector always ignored from the list of key sectors is the one Palestinians have a vast experience in and a multitude of reasons to focus on, education. To be more exact, education under duress is Palestinian’s forte.

A leading Palestinian university commissioned my business consulting firm to recruit private sector investors to co-invest with them in revenue-generation projects, utilizing empty university lands, for the sake of creating new streams of revenue to help alleviate the university’s financial strains. After conceptualizing and pitching over a dozen potential projects over a two-year period, this effort was unsuccessful in bringing any of these investments to fruition. But all was not lost.

Learning from Failure

After this assignment ended, my team sat down to internally evaluate why this effort did not work as planned. We concluded that the miscalculation was from the very outset of the assignment. The university viewed the asset they brought to a future partnership with the private sector as being their hundreds of dunams of unused land, and desired to invest them, but without taking any risk. In hindsight, we concluded that land was not the real added-value a university could offer, not to mention along with a zero-risk appetite, for the university is not a real estate developer nor experienced enough to take even calculated business risks. Instead, we reasoned, the university’s real added-value is its core business, namely providing quality education and engaging knowledge.

A new idea was born—to leverage the vast experience of Palestinian higher education institutions operating in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza Strip, to establish a university outside of Palestine for all those diaspora Palestinians and those in the Palestinian solidarity movement aboard, who are prohibited by Israel from attending Palestinian universities in Palestine. In short, we aimed to export Palestinian higher education to Palestinians.

As a longtime business consultant who works on developing new ideas into companies or not-for-profit organizations, I have become accustomed to starting off my consulting assignments with a declaration, especially when the issue at hand is taking an entrepreneur’s idea and developing it into a business plan. I advise my client that I will only engage in the assignment if the client recognizes, upfront, that conducting a feasibility study for any idea is done just for that reason, to test feasibility, and the client must have the wherewithal to accept a well-argued case that the investment may be unfeasible, and thus must be able to pass on it. I never had a client walk away because of this stipulation, however I can make a list of the ones who were lying through their teeth and who had already decided to invest before a feasibility study was conducted. They merely needed an external consultant to provide the number-crunching and paperwork blessings.

More recently, I learned firsthand how difficult of a request I was making to my clients when I had my firm undertake a pre-feasibility study for my own investment idea, establishing a university outside of Palestine.

Starting in October 2015 and after several years of study and contemplation—under my own consulting leadership—I had to internalize what the facts were articulating, that the idea, albeit novel, was too risky—given level of funding needed and fear that, if established, students would not have unhindered access to the facility—to be able to be recommended as a sound investment, be it a commercial one or not-for-profit one. It was a painful realization to need to pass on my own investment idea, especially one that merged several areas—education, politics, and civil service—of interest, but I did, or am doing so (sort of) with this essay.

The Project

The impetus for the idea was crystal clear: Uniting Palestinians in Education.

The rationale was that Palestine will not be free from Israeli military occupation, nor will restrictions on Palestinians’ movement and access end, anytime soon. After floating the ideas of opening a branch of a West Bank university in Gaza and/or in the Galilee area of Israel, this particular project sought to proactively address the fact that ignoring the systemic, forced fragmentation of all of our people will only contribute to further disintegration of our social and political fabric, thus threatening our national project. Our bold initiative aimed to contribute to building a generation of Palestinians who would be tomorrow’s leaders, but without the geographic limitation placed upon them by a foreign military occupier. Unable to unite in their childhood, we hoped that they may unite in their education and post-education lives, and we wanted to give them a head start.

Step one was to bring on board a leading Palestinian university, an academic partner. The first university that was approached accepted, but with a caveat. They were (and still are) so stretched in terms of human capacity and financial resources, they could do little more than to lend their insights and brand to the project. We considered that enough to get the ball rolling.

The project sought to facilitate the presence of the first Palestinian institution of higher education established outside Palestine for the sake of all Palestinians. We consciously wanted to defy the forced fragmentation that Israel has imposed upon our people ever since its creation in 1948. Our answer to this was to bring together all components of the geographically fragmented Palestinian people so they may physically unite in a genuine Palestinian educational environment, in terms of curriculum, teaching staff, and student body.

A first-of-its-kind venue, this envisioned university was to, for the first time since 1948, bring together Palestinian students from the occupied territory (West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza Strip) to the same classrooms with Palestinian students from inside Israel, from across the region (refugees in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and elsewhere), alongside those Palestinians in the diaspora.

Added to this student body mix, we envisioned those foreigners who were in solidarity with the Palestinian struggle to be students as well as part of the teaching cohort. This conceptualized community become a phenomenon that we started to virtually entertain, day in and day out.

The location chosen to conduct the feasibility in was the island of the Republic of Cyprus. Why Cyprus? Cyprus’ unique geographic position, cradling Europe and the Middle East, and its historic business, political, and cultural ties to the Arab world made it an ideal location for the project. Being one of newest and smallest countries admitted into the European Union (requiring compliance to EU education standards) also made Cyprus an ideally suited venue, given Palestine itself is small and seeks regional inclusion. Furthermore, the country has always been supportive to the Palestinian struggle for freedom and independence, not to mention that Cyprus is experiencing their own flavor of military occupation by Turkey, which would have provided an ideal comparative case study for Palestinian students.

A side benefit to all of this was the expectation that researchers-in-residence would be hosted by the new university to study the ingathering of Palestinians from all walks of life, a unique setup to say the least.

An Objective Study, Almost

I will be the first to admit the study of this project was not fully objective. The consulting team had a higher calling, not least of which was the desire to see Palestinians from all walks of life join efforts in a single geographic location, something unfathomable in today’s political reality.

Three leading Palestinian corporate social responsibility funds heeded our call for seed funds to get a pre-feasibility study started. Although the amount of funds granted were trivial, we felt it was strategic that Palestinians in Palestine registered their material support to reach out to Palestinians abroad.

While conducting the pre-feasibility study, we added to the team of consultants a Palestinian expert in higher education who is based in Europe. Together, we all made a field visit to Cyprus and met with a myriad of potential stakeholders, Cypriot university administrators, Cypriot and Cypriot-based professors, legal experts, investors, and Palestine’s ambassador to Cyprus, just to list a few.

A LinkedIn group called Academic Network for Palestine (ANPs) was established to begin to identify future academics who may have a role in the project. We reached out to scholars who were experts in their field, from Palestine to Harvard University to across the Arab world. In no time, nearly two hundred interested persons subscribed.

We sought out an academic model that would provide for the utmost flexibility and personalized learning, which led us to Quest University Canada, Canada's first independent, not-for-profit, secular university with an innovative pedagogy. We documented all that we learned and continued to refine our model for our intended effect, to bring a group of future Palestinian leaders, each in their respective undergraduate fields, onto a single campus to earn a quality education while meeting their brethren. Quality education and leadership were our guiding principles.

All this effort resulted in a well-developed and conceptualized project—the first Palestinian-affiliated university abroad; an independent, secular, co-educational tertiary education institution, combining the best elements from a multitude of education systems, quality standards, and an international philosophy, all with an indigenous underpinning and all while uniting Palestinians and others in education.

With our pre-feasibility study in hand, we came to our educational partner and seed funders to take the next step, to conduct a full feasibility. This is when the effort was stopped in its tracks. The Palestinian university, our academic partner, was still in no position to contribute, financially or otherwise, to a full feasibility study. Without an academic partner onboard, our seed funders felt that investing any further, when demands at home, in Palestine, were on the increase, was too much to swallow.

Not one to drop an effort lightly, I kept at it. I refused to move the project directory from my desktop, I kept looking for the missing link to be able to proceed.

Investing in Palestinian Education, an Old New Idea

At the launch of our pre-feasibility study, my team and I knew of no other attempt in Palestinian history to use education as a unifying platform. We have since learned otherwise.

Our research led us to our first documentation gem, an article titled, “The Proposed Arab University in the West Bank,” by Mahmoud Falaha (Palestinian Affairs Magazine (Shu'un Falastiniyah) 26 (October 1973), 44-49, PLO's Palestine Research Center (PRC). This fascinating article walks the reader through the entire history of an initial attempt to establish a new Palestinian university.

I recap Mr. Falaha’s 1973 depiction of the facts:

- In light of Israeli distortion of Palestinian society and education, two Arab universities, one in the West Bank and another in the Gaza Strip, were proposed to give Arab students the ability to earn a higher education without needing to travel abroad.

- For this purpose, a preparatory committee was formed in August 1972 in the West Bank and was comprised of three mayors, among them, al-Sheikh al-Jabari and eight other personalities.

- The Israeli newspaper DAVAR (5/9/1972) reported on this project that the Israeli authorities approved the establishment of a higher education institution with four branches, religious studies in Hebron, faculty of arts in Ramallah or Birzeit, graduate studies in agriculture in Tulkarem, and a faculty of natural sciences in Nablus.

- The Israeli newspaper Haaretz (24/9/1972) reported that the preparatory committee took a decision to make a formal request to Yigal Allon, Israel’s minister of education and culture, after it had attained permission from the [Israeli] military governor.

- On 3/10/1972 Allon announced that the Arab Higher Education Institution in the West Bank was established during a meeting he held with al-Sheikh Mohammad Ali al-Jabari and other preparatory committee members. This announcement was reported in the Israeli newspaper DAVAR (4/10/1972) and the report added that the committee requested from Allon that the State of Israel formally recognize the effort taken to establish this Arab Higher Education Institution. It was reported that Allon welcomed the activities of this effort and made note that al-Jabari asked Israel to allow for professors from Arab countries and other countries to be allowed to participate and to allow the committee to fundraise from aboard. Allon agreed to these requests and added that he formally recognizes the committee and its activities and suggested that the committee make use of Israeli higher education institutions.

- The reminder of 1972 and the beginning of 1973 witnessed a flurry of discussions around the creation of a university in the West Bank. On 13/3/1973 the Israeli military authorities approved the establishment of a West Bank university.

- One of the editors at Haaretz (14/3/1973) published the bylaws of the charitable association established for the purpose of establishing the university, along with the project’s milestones. The report stated that the founders expected to start operations in October 1973. It reported that the preparatory committee planned for the university to have presence in several West Bank cities—a law faculty in Ramallah, faculty of arts and social sciences in Nablus, faculty of natural sciences and agriculture in Tulkarem, and a faculty of Islamic studies in Hebron. The initial phase would serve approximately one thousand students. The Haaretz report continued to note that the bylaws stipulate that that university will not delve into political issues and will remain solely focused on academics. Also, based on the guidance of Israeli institutions, the university’s programs will be approved only after ensuring that they do not “incite” against “Israel and the Jewish People.”

- This approval was the subject of much analysis, especially the fact that permission was even given in the first place. On 2/3/1973 Radio Israel reported that the New York Times editorial noted that this move to create a Palestinian university in the West Bank was an important and constructive development to serve Palestinian national aspirations, keeping them far from “destruction and terrorism.”

As documented by Mr. Falaha, some of the very same loaded words that Israel and mainstream media use today were prominent in the discourse from the outset of the military occupation. Another seemingly recent phenomena, that Gaza’s development is separate from that in the West Bank, turns out to not be such a new revelation after all, as Mr. Falaha explains as he continues to log the events of the time.

- About the same time as these efforts were happening in the West Bank, DAVAR (21/9/1972) reported that a delegation from Gaza submitted a memo to Moshe Dayan regarding a project of establishing an Arab university in Gaza. The memo stated that this delegation recently returned from Cairo where they learned that the Egyptians would financially support such a university if it were requested from the residents of Gaza. It also stated that the university would be independent but would need assistance on the academic side of things and would seek assistance from the Hebrew University. It was envisioned that this university would start within two years by opening faculties in engineering, agriculture and medicine and would recruit Palestinian professors from Arab counties and globally, assuming the Israeli authorities granted permission.

- After a long period of silence surrounding the Gaza university, on 1/6/1973 Haaretz reported that a conflict ensued between Allon and Dayan about the establishment of a university in Gaza after the Gazan Israeli military commander had already approved an advanced course on religious studies in preparation for studies at al-Azhar University in Cairo. Allon was against this advanced course out of fear that it was a first step to a full-scale university affiliated with al-Azhar University. Instead, Allon wanted an independent university to be established in Gaza, starting as an advanced school. It was reported that this conflict emerged out of the Labor Party having much deeper concerns that were linked to the politics of “the territories.” Dayan was in favor of this al-Azhar link because he desired all the residents of the territories to be connected, as citizens, of surrounding Arab states, whereas Allon desired in the future that this Gaza university, if independent, could be linked with the one being established in the West Bank. The Allon-Dayan debate was not an interest in education, but rather a debate about the two competing visions on the solution to the Arab territories since 1967, with the Gaza project put on delay and the urgent project being a university in the West Bank.

Mr. Falaha goes on to discuss these state of affairs noting that:

- The ultimate motivation for Israel in contemplating these universities, as well as allowing for municipal elections, was to relieve themselves, the occupier, from their responsibilities toward those people they occupied, all the while putting a civil façade on their military occupation.

- In a reply to a question to Allon in the New Middle East Magazine (London, (May 1973), 7) Allon answered that it was “natural” that such an institution [Arab university] would bring together representatives of all the important West Bank settlements, which could have political ramifications in the future.

- Palestinian Arab reactions were many. Discussions ensured throughout the West Bank about this project and it became clearer that, through the preparatory committee, a Zionist influence was at work promoting this project and directing if from behind.

- The Institute of Palestinian Studies (musasat darasat filiystaniya, 1/4/1973) documented that there was a public outcry against this project and the reasons were 1) the avoidance of Jerusalem as the headquarters for this university, 2) the fear that Israeli hegemony would overtake the university given it is being established under occupation, and 3) disagreement if the university should be independent or linked to the University of Jordan.

- DAVAR reported that there is disagreement between West Bank leaders about the establishment of an Arab university, stating that Hafez Touqan, an elected Nablus Municipality member, published in Al-Quds Newspaper that the preparatory committee, who are self-appointed, did not make sufficient consultations, and were acting hastily.

- The discussion also spilled over into the Arab counties and the Arab League where voices spoke out against this West Bank university and, instead, prompted ways Palestinians could get their higher education at universities in Arab states, including establishing an Arab university for Palestinian students outside of Palestine. [emphasis added]

- At the Arab League’s 59th Session which was held in Cairo in May 1973, the League’s Board for Education took the easy route of passing Resolution 3028 (7/4/1973) which was never implemented, for the League to commission, in cooperation with the PLO, a study for establishing an Arab university for Palestinian students in an Arab country, and for the results of the study to be presented after taking the opinions of the Arab states on their ability to contribute to its funding.

- In essence, the Arab League’s action did not take any action to face the Israeli intention to create an Arab university in the West Bank.

Mr. Falaha ends by noting that:

- It would have been more appropriate for Arab states to open the doors of their universities to Palestinian students and provide them with any needed funding support, thus reducing the overall costs, as well as addressing an immediate alternative to the Israeli plan.

This was not the only documentation gem we found. We also found these articles:

Nabeel Shaath, “High Level Palestinian Manpower,” Journal of Palestine Studies 1, no. 2 (Winter, 1972), 80-95.

Ibrahim Abu Lughod, “Educating a Community in Exile: The Palestinian Experience,d” Journal of Palestine Studies 2, no. 3 (Spring, 1973), 94-111.

and

Muhsin D. Yusuf “The Potential Impact of Palestinian Education on a Palestinian State,” fJournal of Palestine Studies 8, no. 4 (Summer, 1979), 70-93.

You can imagine how excited I was to read Mahmoud Falaha’s and the other articles given four decades later we were facing some of the exact same issues that were being faced in the early 1970s. Likewise, my respect for the PLO’s Palestine Research Center (PRC) and the Institute of Palestine Studies (IPS) grew exponentially as I reflected on the utmost importance of proper documentation of our struggle.

Education, Again

It turns out that this past effort to establish an Arab university for Palestinians was not the only one.

Our consultations with key higher education stakeholders in Palestine, revealed that yet another past effort, this one starting in 1975, had embarked on a similar idea, albeit with a very different intent. A few names were dropped, like that of the late Dr. Ibrahim Abu-Lughod as being the team leader and our interviewee recalled the name “Open University” being associated with this past project. We went searching again.

Then, lo and behold, we found exactly what was being alluded to, a scan of the actual 172-page report with findings of a past feasibility study to establish a “Palestine Open University” (POU). The following excerpt is from the “Summary of Findings” at the outset of the report.

1 Palestine Open University, Feasibility Study, Part I, General Report (U.N.E.S.C.O., Paris, 30 June 1980)

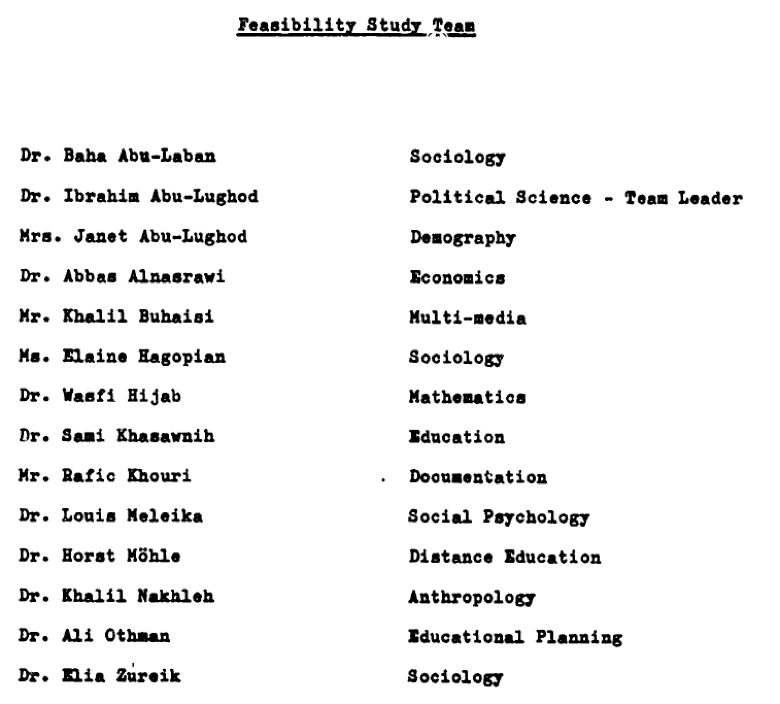

The Feasibility Study Team was indeed led by Dr. Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, but the report revealed a cohort of researchers that all deserve listing:

The actual content of the Feasibility Study was truly revealing. At the outset, the study states the justification for such a project. The first dimension noted is that it was estimated in 1979, four million Palestinians were distributed in various countries across the Middle East, with 2,285,000 located in the “area outside mandatory Palestine,” and 1,175,000 located “within mandatory Palestine” (Israel, West Bank, Gaza). The study noted that a total of forty thousand Palestinians graduate from secondary schools annually, with thirty thousand having “no access whatsoever to higher education.” This first dimension of the “problem” was coined the “numerical” one.

Then, the study went on to other dimensions, “quality” being high on the list. The report stated:

The last sentence of the above passage struck a nerve because it was one of the core reasons we, in 2015, were conceptualizing a Palestinian university outside of Palestine.

The study went on to select a system of learning, referencing many systems across the world. In defense of its choice to adopt an “open learning system” the study noted:

The rationale for this “open” approach is truly shocking when one realizes this was conceived pre-Internet and from a people under serious distress of being dispossessed and operating under a foreign military occupation.

Next came the same pillar which we had constructed as the backbone of our project, an approach to “overcoming the problems of national fragmentation of the Palestinians[!]”

As if the similarities were not already too numerous, the next one was spot on, or rather we were spot on in matching what was already thought-out forty years prior. The curriculum had to be Palestinian for the entire project to make sense; we were not just planning to educate Palestinians, but future Palestinian leaders who knew who they were and where they came from. The 1975 study noted it as such:

But what was going to be taught was not only about national identity, it was also about the need for applied learning, to save a society under attack. The study went to great strides to define the types of courses and programmes needed:

Then came the ultimate question for anything Palestinians want to strategically do; where to do it? The location question challenged the authors in the study just as it did us in 2015. The 1975 study settled on the following:

This is where the two feasibility studies diverged. The reality of the Arab world, as it relates to Palestinians being free to operate, or even the issue of freedom of education in Arab counties in general, changed so drastically over the four decades since this initial study, we sought our project to be as close to the region as possible, but out from under the heavy hand of Arab governments.

The 1975 study very transparently stated that the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation (U.N.E.S.C.O.) was appointed as the “Executing Agency” and contributed 72,000 dollars to the study, and the Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD) contributed 382,000 dollars. These two organizations, along with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), were parties to the Tripartite Agreement in December 1977 that undertook this study.

Something that makes one step back and reflect was that the Palestine Open University (POU) feasibility study cost 454,000 dollars in 1977 (equivalent to approximately two million dollars in 2018 dollars), compared to our inability to secure a fraction of that to conduct our feasibility study in 2018.

Times change as occupation persists

The Pre-Feasibility Study on the Establishment of a Palestinian Open University (August-September 1976, p. 7, Unesco/PLO/AFESC ad hoc Working Group) has one sentence that jumped out and makes the reader seriously contemplate the bigger picture. It stated that “The Palestinian people today face problems of formidable proportions.” Words from 1976! Knowing what has ensued since, I assume the deceased authors are turning in their graves and the living ones are tossing and turning in their sleep.

The fact of the matter is that time matters. Seventy years of dispossession and fifty years of military occupation take a toll on a people, no matter how just their cause or how steadfast they remain. Palestinians are no exception. We are collectively disfigured and internally damaged as Israel continues to rip apart our geographic and social fabrics. But we have not collapsed or surrendered. With every attempt to save our people from further damage, we learn.

Our 2018 university project has taken lessons from the 1970s efforts and, although we hit a bottleneck, we document our efforts so future attempts can pick up where we left off.

There are a few important lessons from our efforts:

All sectors of society must be operational and entail leadership that understands the phase of our development. No sector, be it public or private, can assume the responsibility for developing a sector alone. We learned this early on and, thanks to the wisdom of several private sector leaders with whom we were engaged, we concluded that no matter how noble the effort (uniting Palestinians in education) or how genuine the intention (our private sector seed donors had zero vested interest in the ultimate project they were supporting), responsibilities of a national nature must be undertaken with national leadership. We had taken our first steps without an educational partner having any “skin in the game.” When our pre-feasibility study suggested conducting a full feasibility, our private sector partners stipulated their interest to remain engaged if and only if a Palestinian university stepped up to the plate with tangible resources.

The higher education institutions operating in Palestine, under military occupation, are in no position, financially or resource-wise, to assume the responsibility for educating Palestinians abroad. One would expect the Palestinian Ministry of Education and Higher Education to spearhead such a task, but this is only wishful thinking; although we met with the minister and he welcomed our concept, his mandate is limited to that of the Palestinian education sector under occupation itself, not to mention that the lack of resources available to the ministry make even that limited mandate a colossal challenge.

The responsibility for education of all Palestinians rests squarely with the Palestine Liberation Organization. Thus, the 1970s effort had the correct stakeholders at the table. Today, the PLO is nearly defunct, lacks serious representation, and has limited itself to infrequent meetings, which aim to give the leadership some sense of legitimacy, as weak as that legitimacy may be.

The issue of where to locate such projects remains the Palestinians’ ultimate dilemma. Palestinians are finding it more difficult by the day to find a geographic space where it can plan forward. In Palestine, we remain under the influence of Israeli military occupation. In the Arab region, we remain challenged by the political instability and lack of freedoms. Globally, countries that today may seem like a plausible location, can just as easily became a negative factor as state’s interests shift over time. Cyprus was always friendly to Palestinians, partly given that Greece was an ally to Palestinians. Now that natural gas reserves were located in the waters of Cyprus, and Greece is still reeling from its financial collapse, Israeli overtures to both Cyprus and Greece, with an eye on the gas, are changing the Cypriot view of how much political capital they are willing to spend on Palestine. All of this makes for additional colossal challenges.

Prolonged engagements, such as a seventy-year struggle for freedom and independence, must take into consideration moving targets which are outside of the realm of control. During a recent luncheon in Ramallah with Dr. Merza Hasan, dean of the board of directors of the World Bank Group, he noted that Bill Gates recently visited with the World Bank’s leadership and spoke of how he envisions higher education developing; saying that universities, as we know them today—static, physically-bound, supply-driven institutions—will no longer exist in five years, instead they will become student-driven, competency-granting over a person’s lifetime, rather than degree-granting in a few year program, and will be mostly online! This is a bold prediction and even if off by one hundred percent it is still a realization that must be grappled with.

Takeaways

I come from the school of thought which claims that no serious effort, despite its outcome, lacks learning points. Our project was no exception. I learned a lot.

Geographic fragmentation—and the ensuing economic, cultural and societal fallouts thereof—is a weapon of mass destruction and the Israelis know it. The more we studied the intricacies of the various segments of potential students we were planning on targeting to join the university, the more we learned how each geographic fragment of our people has developed in very distinct ways. Nationalistic emotions aside, the Palestinian student coming from Jericho does not necessarily have much in common today, in terms of career aspirations, with those coming from Nazareth or Gaza or Dubai or Ein al-Hilweh refugee camp or Boston. Israel knows very well that the more Palestinians are denied the right to mingle in a shared space, the more likely they are to never pose a serious threat to the hegemony of Israel between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River.

The Palestinian private sector on the ground in Palestine can only be expected to exert so much effort on national, let alone, transnational, issues. Aside from a handful of firms, many that thrive based on rent-seeking arrangements, the mass majority of Palestine’s private sector are stretched beyond their limits. The societal needs are far too many to expect corporate social responsibility funds to make serious impact. Additionally, the private sector must be the sector of choice for sustainable employment opportunities and fairly compete to keep the cost of living under military occupation as low as possible—that is their ultimate value-added contribution to this phase of our struggle. To expect of them to assume tasks better suited for the political agency, the PLO, to spearhead is asking too much.

The PLO, the ultimate umbrella organization that at one point in its early history had foresight, integrity, and was able to mobilize the best of Palestinian minds to address various issues, including education, has not only become archaic, but worse. Two full generations of Palestinians are growing up having no notion of what such a political agency means, not to mention having the opportunity to engage as one of its members. This is catastrophic and is more the result of self-inflicted damage than that caused by Israeli actions.

Lastly, the ultimate takeaway from this project is not for me, but for those on the other side—our occupiers and dispossessors—who may be enjoying watching another effort to unite Palestinians in education fail. For them, I have a tidbit about Palestinians. I promise you that we, as an indigenous—albeit bleeding—people, are not going to disappear in thin air. You will live with us in some way, shape or form. Our attempt to address our emerging generation’s education is an attempt to ensure that our future dealings will be civil and based in reason and logic, however, if you insist on continuing to rip Palestinian society apart from the inside, I assure you the future generations you will deal with will not be content documenting failed projects in essays.