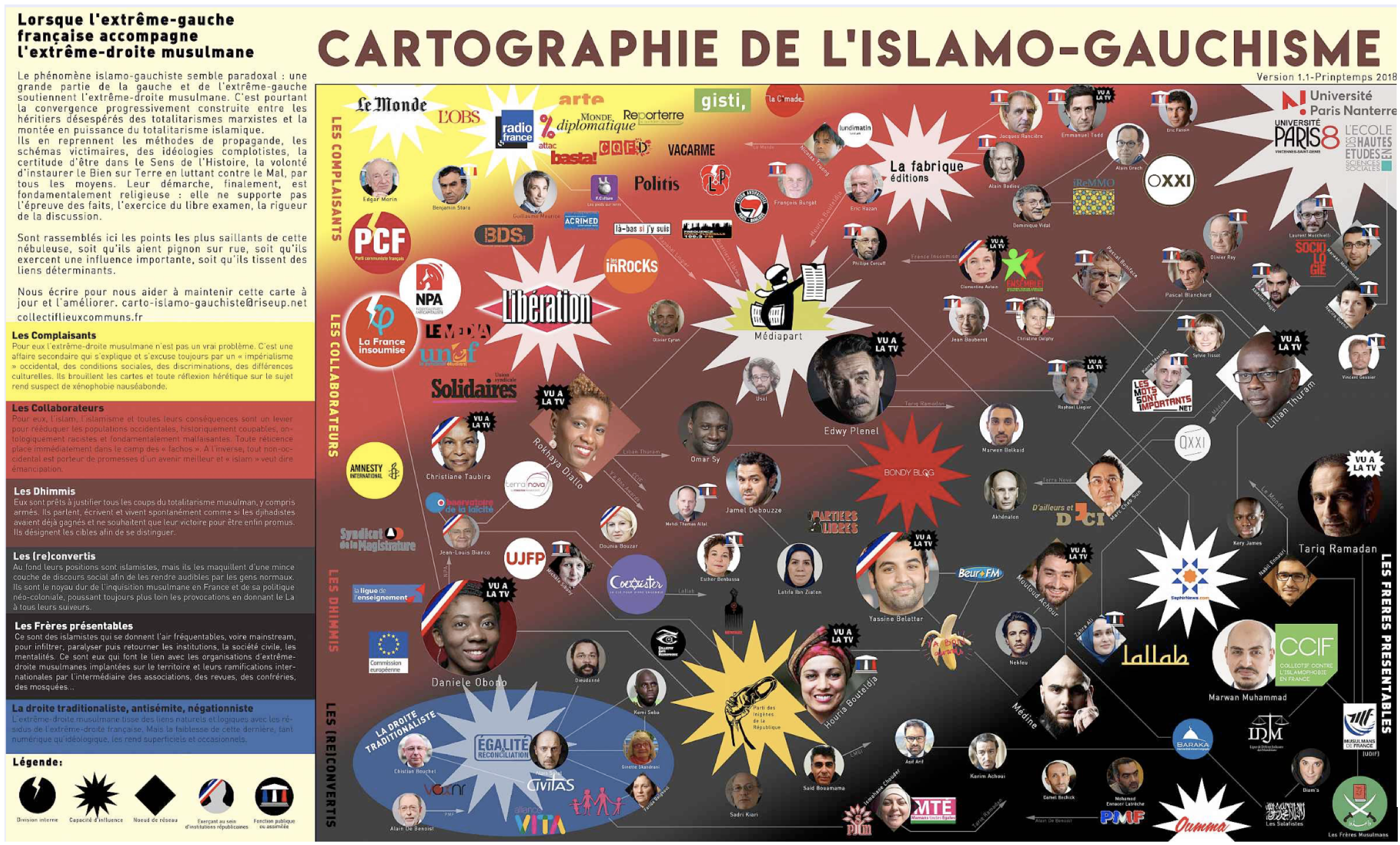

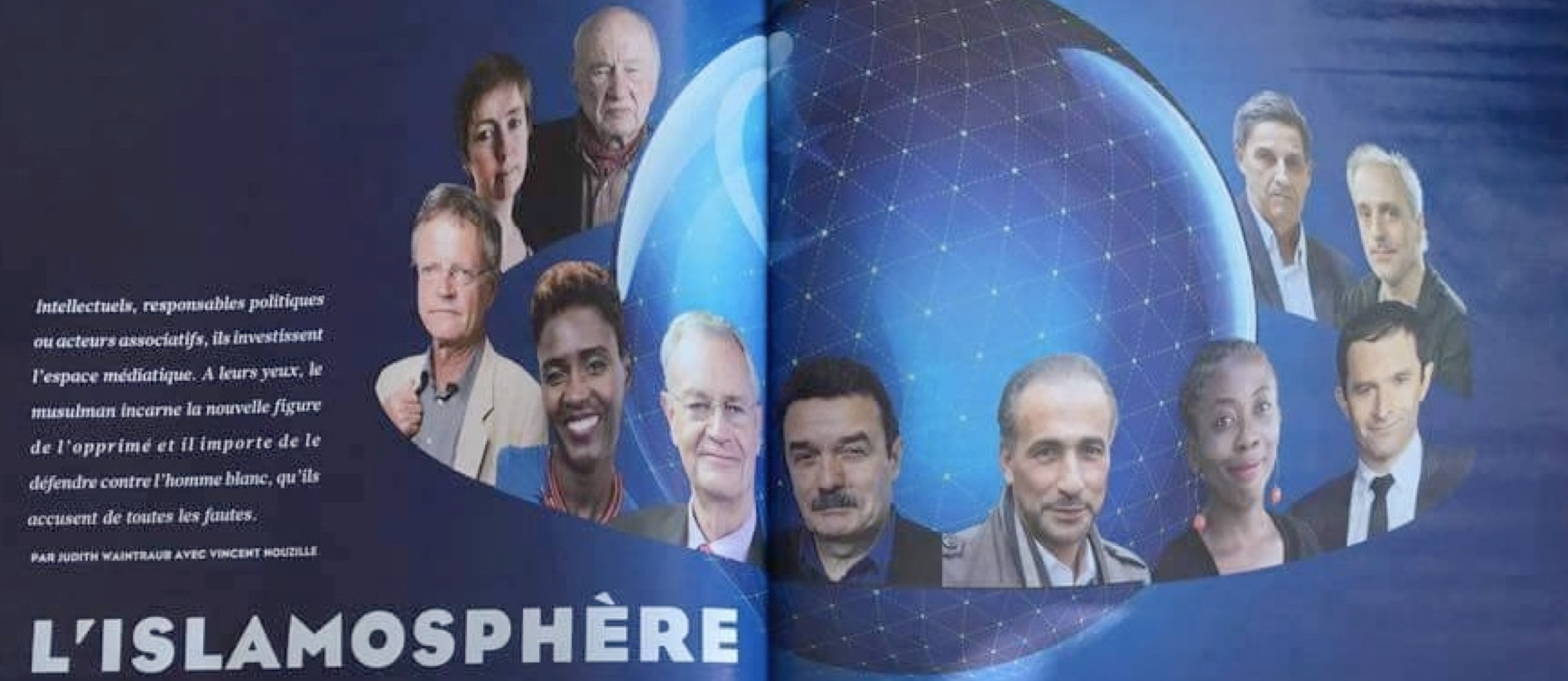

Over the last few decades a new term has emerged in France to indicate a form of dangerous leftist politics: (roughly–and awkwardly–translated as “Islamic-Leftism”). The term is not limited to those who identify with Muslim beliefs or practices. Rather, the accusation can be wielded against those who seemed a bit too eager to defend the right to wear the veil in public spaces, were sympathetic to complaints of Islamophobia, or not quite ready to embrace the hashtag #JeSuisCharlie. The phrase this describes a “sphere” of influence that includes institutions, intellectuals, publishing houses (notably La Fabrique), and musicians (see figure 1). The right-leaning paper Le Figaro has thus described an “Islamosphere” (see figure 2), thereby reproducing an unsettling image reminiscent of the specter of a global Jewish conspiracy that once incited the myth of “Judeo-Bolshevism.” The term combines two historical enemies of the Fifth Republic, killing two ideological birds with one hyphenated stone.

The top image is taken from the far-right website, Lieux Communs. Accessed on 27 July 2018. The bottom image is taken from Le Figaro Magazine, 6 October 2017, pp. 50–51.

Allah and the Laws of Nature

The anxiety that the radical left might find a natural ideological ally with partisans of the Muslim faith has a history that dates to the founding of the Fifth Republic. In 1960 René James, a French scholar of the Muslim world writing for the government, reflected on the relationship between Islam and Communism. France was in the midst of fighting two wars and both: a Cold War against global Communism and a war that was “without a name” against Algerian revolutionaries. In this context, James argued that both Communists and Muslims were inherently against free thought. He noted that a Muslim was “very close to a material Marxist.” If there was a difference it was that “the first one says ‘Allah’ and the second one says ‘laws of nature,” which was “an important but purely formal difference” [1].

If James found this parallel to be obvious, the Soviets did not. In 1956 The Soviet Encyclopedia of religion claimed that “Islam, like all religions, has always played a reactionary role” [2]. Yet as decolonization became a reality in North Africa in the 1950s, Europeans explained the rise in Pan-Arab sentiment as proof of Soviet manipulation. French conservatives and liberals alike argued Communists were using religious sentiment to incite the Arabs, whose Islamic religion made them prone to passionate dogmatism and anti-liberal beliefs. For many European politicians then, totalitarianism was a trait that marked both the partisans of Islam and certain forms of leftist politics.

In the history of the European Left, the word gauchisme has long held a pejorative connotation. It has generally been used to discredit Communist off-shoots that seemed unrealistic or extreme; those who have expressed discontent with the official line of the party were labeled gauchiste by their more orthodox detractors. In 1920, Vladimir Lenin’s published a pamphlet entitled, La maladie infantile du communisme (le “gauchisme”), translated in English as “Left Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder. In it, Lenin attacked German leftists who had broken with the party line. In the 1950s, a host of intellectuals, known as Third Worldists (tiers-mondistes) and inspired by Frantz Fanon’s injunction to “stretch Marxism” in the colonial context, had a falling out with the Party. Trying (but not always succeeding) to offer a less Eurocentric interpretation of the communist tradition earned them the ire of their former comrades. Finally, the question of gauchisme was dealt with in an official manner in 1968 when the term became a label for all dissidents from the French Communist Party. In recent years, this label has become a common way to discredit political opponents, especially among liberal progressistes.

An Insult for All Seasons

The term Islamo-Gauchisme first entered the French public domain in the early 2000s. In 2002 the sociologist Pierre-André Taguieff, analyzing the rise of a “new antisemitism” (nouvelle Judéophobie), defined Islamo-Gauchisme as “a certain leftist third worldism that found itself alongside diverse Islamic currents in pro-Palestinian mobilizations”[3]. While being too “Muslim-friendly” first raised red (or green) flags in relationship to Palestine, it gradually became a much wider ideological tool. The 2003 law that addressed the question of “ostensibly religious” symbols in the public space was followed by a set of discussions around the question of Islam and laicite that became even more polemical following the 2015 terrorist attacks.

The far-right has predictably used the term to decry the threat of open borders. Marine Le Pen has invoked Islamo-Gauchisme to argue that liberals who tolerate immigration are responsible for a rise in radical Islamism. “How many Mohamed Merahs (are there) among those immigrants who are non-assimilated?,” she asked, referring to the gunman who shot seven people in three attacks in 2012. A confusion between the threat of Islamic terrorism and the visibility of Muslims in the public space was especially prevalent after the attacks on Charlie Hebdo and the Bataclan in 2015. When interviewing the Franco-Senegalese footballer Dem Ba, the sports commentator Stéphane Guy asked Dem Ba about his habit of conducting a Muslim prayer on the pitch. When Ba responded that he saw no issue and hoped for a world of tolerance, Guy continued his interrogation. He eventually posed the question: did Dem Ba consider himself to be a Muslim or an Islamist?

Allegations of “Islamo-gauchisme” are also widespread on the center-left. When the 2017 Socialist candidate Benoît Hamon explicitly supported a more open Republicanism, the right promptly attacked him for being a candidate of the Muslim Brotherhood. Hamon certainly occupied the socially inclusive fringe of a party whose more authoritarian members – most notably Manuel Valls – have frequently used the accusation of Islamo-Gauchisme to discredit their opponents. Intellectuals supporting Valls’ reorientation of the Socialist party also founded a so-called Republican Spring. This group explicitly sought to extend Republican, secular values against what they labeled as défaiseurs identitaires (“un-makers of identity”). One of the key figures of this movement – political scientist Laurent Bouvet – has recently penned two books whose titles speak to its central ideological pillars: L’Insécurité Culturelle: sortir du malaise identitaire française (2015), which argues that cultural claims in the public space have led to an emphasis on diversity rather than equality, and La Gauche zombie. Chroniques d’une malédiction politique (2017), which also sees intersectionality as an obstacle to constructing a dynamic political force on the left.

The Secularist-Far-Left

On the Secularist-Far-Left (a term I will use to refer to a group that includes Communists, as well as Trotskysts and Anarchists) we also find a critique of the déviation that has led to a focus on identity and race. For example, there is a long-standing clash within the Trotskyist movement between the secularist Lutte Ouvrière and the libertarian Nouveau Parti Anticapitaliste (NPA). For many, the NPA’s openness on social issues like religion, and their decision to run a veiled candidate, is simply unacceptable. Similarly, when the Leftist populist Jean-Luc Mélenchon got a bit too friendly with Muslims by creating a coalitional movement known as La France Insoumise, he too faced accusations of Islamo-Gauchisme.

Writing on the fracturing of the far left, Le Monde has echoed Daniel Bensaïd’s concern regarding applying the principle of “non-mixity,” first deployed by feminists in the 1960s to questions of ethnicity. He then curiously claimed that this may lead to the “form of intolerance that Frantz Fanon called ‘antiracist racism.’” Yet Bensaïd misreads Fanon, attributing the phrase to Fanon when it first appears in Jean-Paul Sartre’s Orphée Noir. Moreover, when Fanon does use this term in Black Skin, White Masks he criticizes Sartre for a methodological commitment that is also at the heart of the debate on Islamo-Gauchisme: the tendency to sublate race to the universal dialectic of class.[4]

The class between “racialized” activists and the Secular-Far-Left has often used bookstores as a battleground. In January 2016, La Discordia in Paris held an event entitled Islamophobie: du racket conceptuel au racket politique (“Islamophobia: a Conceptual and Political Racket”), which sought to discuss how the notion of Islamophobia made any critical discussion of religion impossible. In October of the same year, Mille Bâbords in Marseille hosted a discussion entitled S’opposer au racialisme (“Opposing Racialism”), which was interrupted by militants who distributed pamphlets attacking the organizers for being Eurocentric in their insistence on class struggle.

The owners of Mille Bâbords later wrote a letter of solidarity with La Discordia that clearly lays out their anti-clerical arguments, which can be summarized by two points: First, radical leftist politics cannot, and should not, exist alongside religion. The French socialist Auguste Blanqui’s famous slogan “no gods, no masters,” remains an important secular commandment; a critique of technology and science must also condemn the obscurantist tendencies of religion (“Les ténèbres de la raison ne peuvent faire oublier celles de la religion”). Their argument also contends that the Pandora’s box of religious sympathy leads to “doubtful alliances with mosques” and therefore an embrace of reactionary voices. Secondly, religion, which plays a fundamentally conservative role, cannot be the vehicle of revolutionary aims. In the historical examples when religion did militate for leftist aims–for example, in liberation theology and during decolonization–it was ultimately forced to submit to transcendental beliefs and hierarchical structures. In short, they maintain (contra the Asadians) that anti-clericalism cannot be considered as a form of religious conviction.

For others on the Secularist-Far-Left, the appearance of the Muslim as a mobilizing political figure has replaced the truly universal trope of the Worker. While they concede that discrimination against North Africans exists, they maintain this treatment should be understood on the basis of geographical origins rather than religion. To insist on structural violence against Muslims, they claim, denies the social plurality of this population, forcing individuals from North Africa and the Middle East to adopt a religious label with which they may not, in fact, identify. It also displays what Sadik al-‘Azm, and later Gilbert Achar, have called “orientalism in reverse,” reifying the dichotomy between East and West advanced by Edward Said, and upholding Islamic culture as the main source of authenticity. For some on the Secularist-Far-Left, the concern for Muslims expressed by the “identarian” left is a glorification of Islam and thus also commits the error of “orientalism in reverse.” Rather than seeing the concern with Islamophobia as rooted in a set of structural and historical circumstances, the Secularist-Far-Left sees a glorification of the figure of the Muslim that is a mirror image of Orientalists' portrayal as Islamic society as static and regressive.

This argument is thus also rooted in a certain posture taken against Anglophone theory (or, more precisely, the Anglophone reading of so-called “French Theory” denounced scholars like François Cusset). Much like the postwar threat of consumer society, many French leftists accuse the Anglophone empire of pedaling a specific product of advanced capitalism that erodes the possibility of radical politics: post-colonial studies. While the critique of cultural imperialism may be well-founded, this discourse also serves to systematically discredit an entire body of literature. Indeed, what is often written off as American-style “identity politics” may pose certain challenges when applied to the other side of the Atlantic. Yet hyphenated identities, which have long seemed anathema to French Republicanism, have already arrived in the Metropole.

No Gods, No Masters?

I suspect that at least some of the above points–including a critique of postcolonial studies and identity politics–may gain a certain sympathy with American leftists. Anglophones in the United States will note certain parallels with the class versus race debate that has emerged after the election of Donald Trump. Yet France’s particular history–of socialism, religion, as well as colonial immigration–necessarily imbues this debate with a different vocabulary.

Blanqui had a specific enemy in mind when he penned his famous slogan “no Gods, no masters”: the Catholic Church. In 1869, two short years before the Paris Commune, he pronounced that Catholicism had been “no more useful for humanity than smallpox, the plague or cholera.” Yet, the anti-clericalism of French socialists also has a specific history. For example, Blanqui was close to the Saint Simonians, who aided in the colonization of North Africa. His universalism certainly did not stop him from portraying Mehmet Pasha of Egypt as a barbarous despot or believing in the superiority of modern civilization.

To use Blanqui’s anti-clerical slogan in response to the contemporary issue of Islam in France thus poses certain issues. The Catholic Church was a dominant institution that supported reactionary forces (royalists and Bonapartists). Islam in France is a minority religion with no centralized structure (apart from that imposed on it by the French state). Moreover, Islam appeared on French soil largely as a result of colonization, which was encouraged as a balm to soothe fears of the “dangerous” (revolutionary) classes in 19th century France. Socialists who, like Blanqui, critiqued Catholicism in the 19th century, did so on the basis of the class violence it propagated in France. They had much less to say about how this violence was linked to the colonial racism carried out in the name of Islamic difference. Thus, a philosophical tradition used to combat the reactionary order defended by the Catholic Church does not necessarily give us a set of political tools to address Islam’s role in the French body politic.

Nevertheless, perhaps we should not dismiss the dangers of identity politics too quickly. After the recent World Cup countless articles were published regarding the African “identity” of the French players. This was often made with blatant disregard for the players’ own identifications. Commentators seemed to take Paul Pogba or Benjamin Mendy’s insistence on their French culture as a public relations stunt. Yet it takes a certain amount of self-delusion to dismiss the importance of French identity in Pogba’s pre-match speech, which used the image of future generation of French citizens to motivate his teammates.

Yet a frustration with identity politics cannot equal a dismissal of race as an analytic category. Unlike identity, race is necessarily structural and always articulated in a historical formation. Moreover, while an identity can be altered by the individual, race cannot. O.J. Simpson may not have identified as black, but the racial politics of his sporting and criminal trajectory could not erase this fact. Similarly, individuals cannot opt out of being read as Muslim. To believe that this is possible is to ignore the long history of colonial and post-colonial racism that discriminated on the basis of religion. More importantly, it overlooks the fact that at key moments in French history, Islamic beliefs had little to do with the legal category of being a Muslim.

Colonial laws made to discriminate against Arabs did not point to their biological or physical difference (see the Indigenous Code of 1881 or the Sénatus-Consulte of 1865) but to the “fact” of their religious belonging. If an individual wanted to apply for citizenship in colonial Algeria, for example, they first had to give up their attachment to religious law that governed death and marriage. To many Muslims, this was tantamount to heresy. The message was clear: the French republic was color-blind in that it did not ask the color of your skin, but it certainly did concern itself with religious categories. When other European populations were granted French citizenship in 1889, joining the Algerian Jews who had achieved this feat in 1870, Algerian Muslims had to wait until 1958. [5] Moreover, even if an indigenous Algerian converted to Christianity, the state recognized them not as Christian, but as a “Muslim Catholic.” Thus, the claim that Muslim identity has historically been attributed on the basis rather than a feature of structural racism is a basic misreading of French colonial history.

Nevertheless, some on the Secularist-Far-Left insist that Islamo-Gauchistes commit a category error in assimilating under the rubric of “Muslim” those who in fact have few–if any–religious beliefs. As analysts such as Stuart Hall have argued, notions of origin, biological difference, and religion have always been closely intertwined. Islam, once understood as an obstacle to the mixing of populations, was also used in nineteenth century texts to denote people from a certain geographical location as well as the relative purity of certain bloodlines. When the colonial state determined that someone was a francais musulman, no government official inquired about their knowledge of the Qur’an or place of birth.

Contemporary statistics that point to employment rates and workplace discrimination, while hard to procure in a country where such questions are not asked by the state, point to a similar conclusion. When applying for jobs in France, the appearance of the first-name Mohammed on a CV has negative effects for the candidate–regardless of whether or not he fasts during Ramadan. Thus whether or not someone identifies as Muslim, they face a system that discriminates based on last names, accents, or clothing styles which are perceived as Muslim. This also reveals a basic methodological difference at stake in the decision to use race as a conceptual framework rather than identity: a fascination with personal identity can actually obscure an analysis of racial formations. This point is often lost on both Anglophone champions of hybridity as well as French partisans of the Secularist-Far-Left.

The Muslim and the Worker

The claim that the appearance of the Muslim has killed off the heroic and universal symbol of the worker is even more pernicious. Early this year, railroad workers won a lawsuit against France’s national railroad company, the SNCF for discrimination. The problem? The contracts of Moroccan workers recruited in the 1970s did not give them the same rights as their European comrades. Here, a classic example of proletariat – railroad workers – had to go to court to get recognized as a universal Marxist subject. For these individuals, the brotherhood of class did not save them from the sharp edge of race. Historically speaking, it is impossible to define the notion of the “working class” without reflecting on the functioning of racial categories.

The functioning of race was central to the construction of a “white” working class in France. As Tyler Stovall has documented, after the Great War, French factory workers became more tolerant towards once-unwanted European immigrants – namely the Spanish and Portuguese.[6] The definition of the working-class was inseparable from the exclusion of black and North African colonial workers that had recently arrived in French factories. In the United Kingdom, Cedric Robinson has highlighted that the making of the British working class (to invoke E.P. Thompson) relied on a self-conscious differentiation from Irish workers, who were considered as racially inferior.[7] Nor was this racism categorically separate from religion. Indeed, the racism experienced by Irish immigrants coming to the US, understood to be “lazy, clannish, unclean, drunken brawlers” was tied to anti-Catholic sentiment, culminating in the 1798 Alien Acts.

Class consciousness and racial structures have always gone hand in hand despite universalizing pretenses to the contrary. Taking “race” out of capitalism–much like the recent decision to take it out of the French constitution–is another gesture at a fictional colorblindness. Addressing the historical structures of race as constituent of class struggle is far from pandering to American identity politics. Instead, it takes French history seriously, from the utopian socialism of the nineteenth century to the present day.

Whose Wretched of the Earth?

Some on the Secularist-Left have argued that like the colonized subjects of old, Muslims are victimized by their portrayal as the Wretched of the Earth. Those who automatically take up the defense of Muslims (capital M), thus also have a tendency towards conservative values and liberal economics. But leaving aside the more obvious targets for such a critique (such as Houria Bouteldja and the Parti des Indigènes de la République), must a critique of Islamophobia, or an openness to the inclusion of religious ideas, necessarily imply a reactionary political program? After all, various Muslim figures - from Ali Shariati of Iran to Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria - articulated an authentically revolutionary program based on Islamic principles. This echoed liberation theology in Latin America, which also went against the holy universalist grail of European socialism.

The phrase Wretched of the Earth of course famously appears in the opening lines of the Internationale (debout, les damnés de la terre). It is also often associated with the writings of Frantz Fanon, who was a seminal figure for the Third Worldism. According to his most astute biographer, David Macey, Fanon’s appropriation of the term was mediated by another source: a poem written in the late 1930s by the founder of the Communist Party of Haiti, Jacques Roumain. The work, entitled “sales nèges” tried to combine an awareness of racial violence with the language of Communism. He wrote that only when the “dirty” blacks, Jews and Arabs learned the language of the Internationale would they rise up to form an international leftist alliance.

Like Ben Bella and Shariati two decades later, Roumain too saw that the structures of race, religion, and capital would need to be conjugated together. A gesture at racial capitalism, a concept that insists that racial categories were constituent of capitalism, makes this poem a biting critique–of the political right and the Far-Secularist-Left. The “threat” of race, as David Theo Goldberg has called it, explains why the figure of the Islamo-Gauchiste provides such a rich imaginary.[8] The term allows for a curious alliance among warring political factions, allowing all of them to ignore the insights of critical race studies while simultaneously misreading the historical formation of capitalism in Europe.

________________

[1] Nantes, Diplomatic Archives (CADN), 21PO/151, René James, “Étude sur L’Islam,” July 1960.

[2] Nantes, Dipolmatic Archvies (CADN), 21PO/151, “Islam dans la grande Encyclopédie soviétique,” Revue de Presse, December 1965. Islam in the Soviet Union. (p. 10 of pdf).

[3] Pierre-André Taguieff, La Nouvelle Judéophobie. La Fayard, 2002.

[4] I would like to thank Anthony Alessandrini for clarifying this point in an earlier draft.

[5] Before this date Algerian Muslims were legally considered to be French subjects but not citizens. The Statue of Algeria (1947) granted Algerians in France full citizenship (limited to Algerian men) and allowed for free circulation between Algeria and France. Yet Algerian Muslims living in Algeria had to wait until 1958 to be given unconditional French citizenship.

[6] Tyler Stovall, “The Color Line behind the Lines: Racial Violence in France During the Great War.” The American Historical Review, 103(3), 1998, pp. 737-769.

[7] Cedric J. Robinson, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. University of North Carolina Press, 2000 (1983).

[8] David Theo Goldberg, The Threat of Race: Reflections on Racial Neoliberalism. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.