It happened only weeks after the Highway of Death, where the US-led coalition attack claimed the lives of tens of thousands of retreating Iraqi soldiers in the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War. As the few famished survivors reached Basra, an angry soldier raised his machine gun and began to shoot at a huge portrait of Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s infamous dictator and the West’s close ally up until his invasion of oil-rich Kuwait on 2 August 1990. That moment on 2 March 1991 marked the beginning of the Iraqi uprising in fourteen (out of the eighteen) Iraqi provinces. It signaled a point at which Saddam’s government lost control of most of Iraq, leading to a countrywide military campaign that brutalized civilians in the south and north of Iraq, executing protestors and burying them in mass graves. All of which took place mere days after the United States declared victory, and under the watchful eyes of their air force patrolling Iraq’s skies.

“Well, they started the fight and the wall is the weapon of choice to hit them back.”

Banksy, Wall and Piece 2006

On a spring day in March 1991, Baghdad woke up to the news of a military siege of the al-Thawra city (as known as “Saddam City,” and changed after 2003 to “Sadr City”), one of the densest and most impoverished of Baghdad’s neighborhoods. The Iraqi government at the time claimed that heavy weaponry was hidden in the area and dissident fighters were barricading themselves in this neighborhood. In response to the government’s narrative, rumors began seeping into the scolded streets of Baghdad, and it was then that “the wall” story came out. The story told that al-Thawara was being punished for the red graffiti plastered on a large wall in the neighborhood that read, “Iraq is for sale. For more information, refer to Saddam Hussein.” The wall was promptly destroyed by security forces and all of al-Thawra City came under siege, brutalized by random arrests. The government understood by now that the situation was so fragile that a simple act of dissidence could lead to a full-blown uprising, and they could not risk that in the capital. Yet, walls all over Iraq started following the lead of that first graffitied surface, and soon became covered with messages of protest and anti-government graffiti, replacing the thousands of Saddam’s portraits planted in every corner of every neighborhood.

One American invasion later and hundreds of thousands of lives lost, Iraq remains dangerous for anyone who would dare object to those in power. Almost every political figure or party in post-2003 Iraq has their own armed militia. The situation is chaotic and threats are easily carried out. Portraits and murals are back, but with new faces—religious figures and powerful political opportunists covering the walls of every Iraqi city and town. Slogans now glorify the new leaders, and threaten dissenting voices.

By witnessing the state of these politics and the 2006-2008 sectarian civil war, many young Iraqis have grown to be tired and frustrated. Like their fellow dissidents years earlier, the youth have started expressing their frustration with the new rulers using their cities’ walls. They have organized themselves and created independent civil movements, aiming to replace the sectarian messages with ones of peace and unity, and have painted on the walls and concrete partitions that were dividing Baghdad according to sects.

A Question Mark Means a Possibility

He considered Sadr City, where he was born and raised, his canvas. The twenty-something-year-old artist started his forays into graffiti in early 2011, creating his murals in odd places around the city. S.A. used stencil, a graffiti style developed by Banksy*, as his street art medium. His work is cynical, sarcastic, and very critical of the political and social realities in Baghdad. This is something that provoked the anger of people in power, and landed him a spot on their blacklist. It eventually forced him to leave the country after receiving several threats to his life.

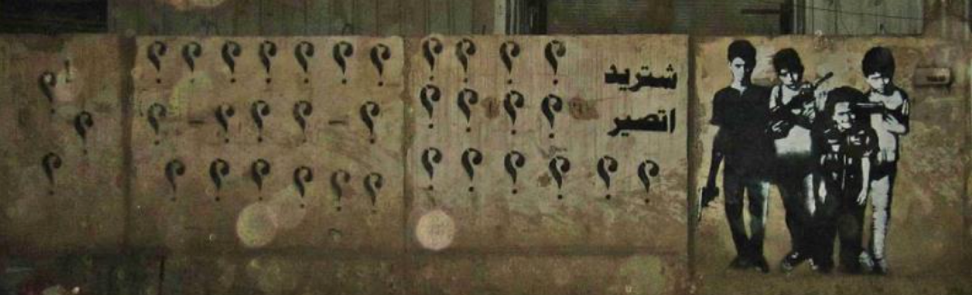

His mural, What do you want to become?, occupied a large wall in Sadr City, depicting the figures of four children perhaps pausing for a photo. Three of them were carrying guns while the fourth child stood in the front, smiling and seemingly totally indifferent about the gun pointed right at his head. Written astride to the children was the question: “What do you want to become?” It is a question that children are usually asked. The adjacent walls were covered in question marks, potentially asking what the possibilities are for the future of those kids, for all Iraqi kids. Will they inevitably be armed militia members or their victims, or are there other possibilities?

[What do you want to become? Mural by S.A. 2011.]

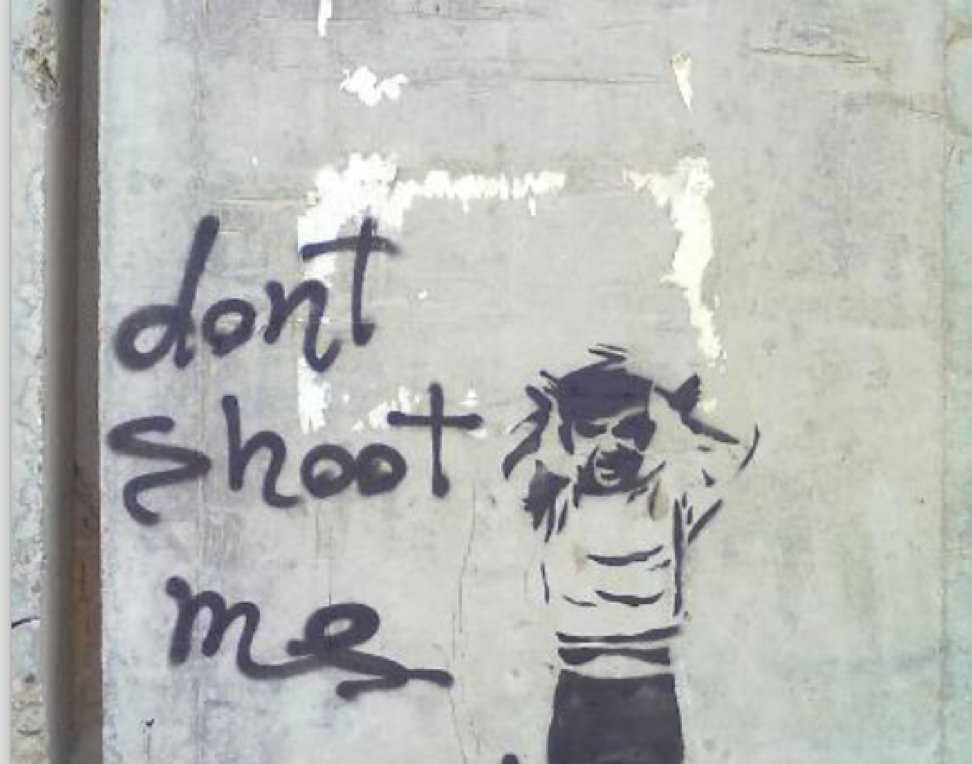

In another mural, Don’t shoot me!, S.A. also used the figure of a child putting his hands on his head as a sign non-resistance, inviting us to imagine a shooter with a gun pointed at the child. Or perhaps it puts us in the position of the shooter, drawing our attention to the repeated violence that has taken place in the city since the American invasion. Not only does the violence claim the lives of many children and their parents, it has forced children to think it has become an inevitable fact of life.

[“Don’t shoot me!” Baghdad 2011.]

It’s Not Always Funny

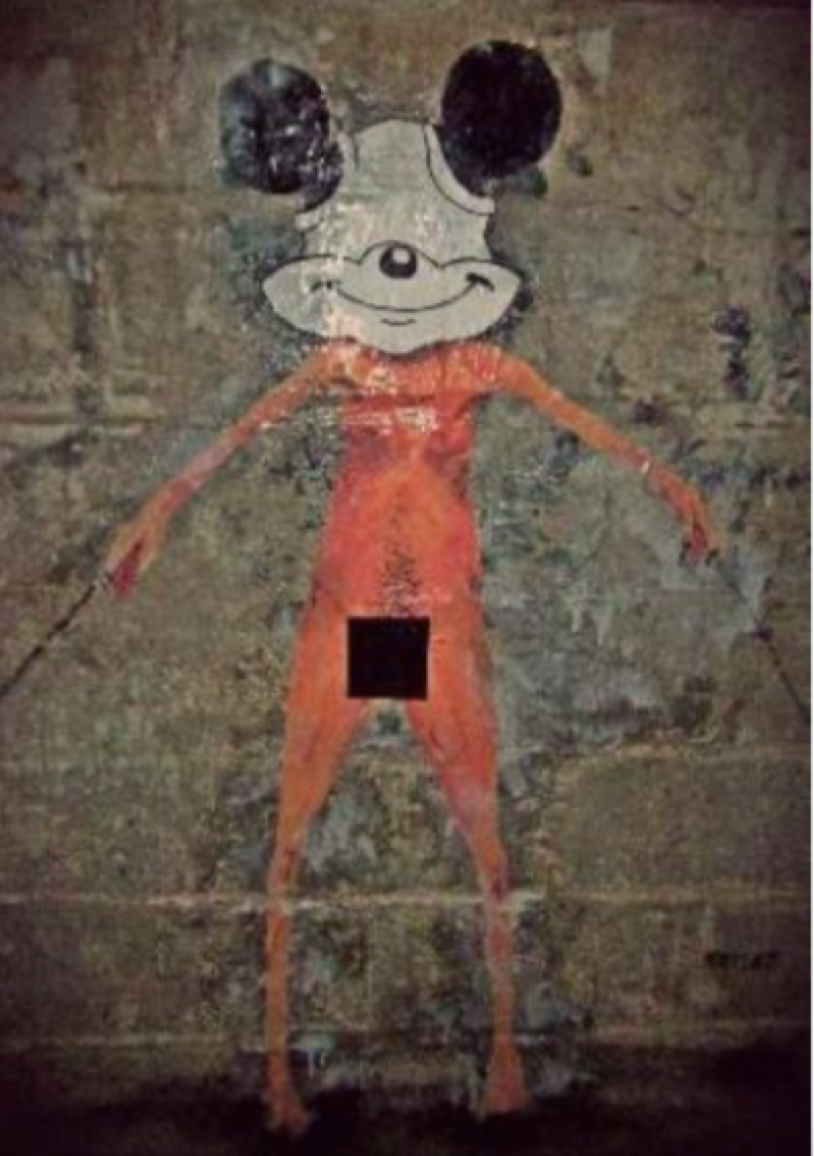

The sarcasm and irony S.A. employs make his work powerful. His images remind us of the stark reality of a country in a constant cycle of violence and corruption, a cycle so vicious, it is painfully surreal. This sentiment is captured distinctly in a mural depicting Mickey Mouse, the iconic Disney character—standing bare naked, his arms spread wide, his fingers connected to electric wires and his head covered with white underwear, concealing his eyes but leaving his smile out for us to see. It evokes the infamous images leaked in 2004 of the abuse of Iraqi prisoners, committed by US officers in the Abu Ghraib prison that the United States operated as a detention center after 2003. Does Mickey Mouse here, with the plastered smile on his face, represent the American promise of democracy in Iraq that went horribly wrong?

[Baghdad, 2012]

False promises were not limited to the US administration; Iraqi governments since 2003 have failed to fulfill their promises of maintaining security, fighting corruption, or building any kind of national system to secure the future of Iraq. And although former Prime Minister Hayder al-Abaddi enjoyed some amount of a popularity amongst Iraqis, he was known to be too weak, submissive, and incapable to be able to impose the necessary policies that would constrain powerful players, parties, and militias.

[PM Abaddi the Clown, Baghdad, 2018]

One of those powerful players is Qais al-Khazaa’li. He is the founder of one of the most notorious militias in Iraq, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, and is himself a controversial figure. His militia has been responsible for instigating sectarian violence, kidnappings, and the preparation of “hit lists” targeting their opponents. However, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq was also part of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), which played a significant role in liberating Iraqi cities from ISIS control. “I want you with me!” is a mural S.A painted of Qais al-Kazaa’li, wearing his usual religious attire and the Iraqi flag around his neck. The mural is aesthetically simple with an undercurrent of complexity. The look on al-Khazaa’li’s face says it all: “Be with me or else!”

[“I want you with me!” Baghdad 2018]