The Establishment of the Companies: Why Chekka?

Chekka, Enfeh, and Heri are Koura's natural coast, regardless of the district they belong to (administratively). Before the cement companies, the coast of Koura lived off the plain in its midst. Men worked in agriculture and fishing while women worked in salterns (in Anfeh and Chekka) and harvested olive and tobacco in the rest of Koura's towns. Enfeh and Chekka have the richest water resources on the Lebanese coast. They’re floating on a large pool of groundwater that has its source in Tannourine. Salt was the primary source of livelihood, and people would come down from mountain tops on mules to exchange their loads of mountain products for salt.

With these words, Mr. Hafez Jreige (born and raised in Enfeh) described what he called "Koura's natural coast" during a public gathering held last month by Public Works Studio, which brought together the fishermen of Chekka, Enfeh, Heri and diverse stakeholders concerned with environmental issues in Koura. Everyone in attendance nodded in agreement with Mr. Jreige's words, bemoaning the many resources they had lost.

How did the coast of Koura and its hinterland turn into an industrial zone strewn, often haphazardly, with factories, companies, and quarries? The transformation of the region’s very constitution was, to say the least, socially, economically and environmentally devastating. Industries have not been able to provide a sustainable alternative to agriculture and marine activity as key income sources. So, over time, available options have become very limited.

In 1931, on the coast spanning Heri, Chekka, and Kefraya, the first cement factory in Lebanon was established by the Lebanese Cement Company. Archbishop Antoine Arida and the Maronite Patriarchate founded the company in partnership with Société d'Entreprise et de Réseaux Electriques de Paris in 1929.[1] The company’s production increased rapidly, from about forty-nine thousand tons in 1938 to one hundred thousand tons in 1940.[2] About two decades after work began in the Lebanese Cement Company, another cement factory was established on Chekka’s coast: a subsidiary of Cimenterie Nationale (presently known as Al Sabeh), formed by the Sehnaoui, Esseily, and Doumit families.

At that time, there was no Ministry of Planning, no urban planning laws, and no land use regulations for any of the towns in and around Chekka, or even at the national level. The Lebanese Cement Company was established under the French Mandate and was linked with European interests and local allies. According to a 1937 article published in al-Nahda magazine, “Chekka’s cement company does not pay a single piaster to the Lebanese treasury for the millions of tons it produces, yet it receives privileges and protection unknown to any other national company as yet.” The only legislations that existed at the time when the two companies were established focused on regulating the quarrying and stone crushing sector (1935) and on imposing provisions on the cement industry (1938). But they lacked the comprehensive vision or planning required to guide land use and choose the locations of industrial facilities. So, why are these companies located on the Koura coast?

The main factors for investing in this area were its proximity to the sea and the quality of its soil, which consists of two types: limestone and clay.[3] The availability of water as a source of energy and as part of the production process (Jaouz River and the Jaradi Spring), and of the sea for an export port created ideal conditions for the establishment and expansion of the companies. In just a few years, the number of industrial factories on the coast of Chekka increased. In 1950, a fiber cement (“Eternit”) factory was established to manufacture asbestos panels and pipes (which later proved to have caused the deaths of dozens of workers with lung cancer).[4] In 1961, the Société Libanaise des Ciments Blancs S.A.L. was established. During the 1950s and 1960s, both cement companies significantly expanded with the support of the Lebanese government, including obtaining permits to transport cement in 1956 (contrary to the provisions of the 1938 decree), to occupy Maritime Public Property (contrary to the 1925 law which defines Public Property), to establish a customs office and independent ports for export (1967), and to invest the Jaouz River and the Jaradi Spring (effectively depriving the inhabitants of them).

All this was done without considering the economic, environmental, and health implications of the industries. “Foreign shareholders in the cement factory were aware that the company was causing pollution,” says Mr. Jreige. “So, they distributed eucalyptus trees to all the municipalities and workers in the area and encouraged them to plant them without telling them the main reason, which is that eucalyptus trees absorb dust from the air. Over time, companies began to recruit farmers and fishermen by luring them with permanent jobs and fixed wages, which encouraged many to quit fishing or farming. The companies gained enthusiastic supporters, and workers started bringing their sons to take over their work.”

In the early 1970s, the government issued decrees to organize small parts of Koura and its coast: the land use planning in Kfarhazir in 1970 and the General Master Plan for Northern Coasts in 1972. The latter noted the presence of two cement factories and defined industrial areas in Chekka, Heri, and Enfeh. These two “local” legislations were not sufficient to control and regulate the companies’ expansion or the dust infiltrating the area. In parallel, national policies had significantly contributed to the success of these companies and their development. In 1993, under continuous political cover and support due especially to both companies’ relationship with the Maronite Patriarchate and the political powers in Zgharta,[5] the Lebanese government banned the import of cement from foreign markets, which led to repetitive increase of cement prices. Our study of land-ownership and urban planning decrees even suggests that the state of “non-regulation” at the local level was deliberate and instrumentalized to the benefit of the cement companies at the expense of everything else.

The Sprawl of the Companies: How Were Lands Sold and Quarries Established?

The opening of the cement factory in Chekka coincided with the launch of operations to extract raw materials from neighboring towns. It was clearly in the interest of companies to place their quarries near the factories to gain time and reduce the cost of transporting these materials. “If the quarries are closed,” an Amioun resident explains, “the factories will not stay here. Today, transport trucks charge seven or eight dollars per trip. If the companies want to bring in soil from licensed quarries in the Bekaa,[6] transport truck fees would cost them three hundred dollars per trip to Chekka.”

Consequently, unauthorized quarries spread in the towns of Koura. The approach to land purchases was a key factor in the expansion of companies and their control over the region’s fate and resources. From the beginning, companies took advantage of the neglect known by a number of small villages around the area. It was easy for them to lure landowners in marginalized villages to sell their properties and receive payment in cash, enabling companies to secure a source of cement for many years at cheap prices.

In 1967, the Cimenterie Nationale began digging large pits in the Koura plain to extract clay, amid about two million olive trees.[7] Koura residents tell how the company bought soil from landowners, causing damage and soil creep to neighboring properties. This in turn allowed the company to buy them cheaply (“for mere piasters”), especially after the owners realized the fate of the plain. Over the course of sixteen years, a total surface area of one million square meters was dug out of the Koura plain, making up one-ninth of its size, and reaching depths of fifteen to twenty meters. Today in Amioun, an activist explains,

the average value of one [square] meter of land is 350 dollars, but it is only worth twenty dollars here. People have no other solution but to sell to the companies because they are the only buyers there. Companies do not pressure people into selling their lands; people are compelled to sell them out of necessity. But when someone does resist and refuses to sell their land, the companies tempt them by offering an additional amount.

In the town of Badbhoun, for instance, land purchases began in the early 1960s. By 1962, the Cimenterie Nationale had acquired 900,000 square meters, or more than three times the area of Horsh Beirut. This area constitutes the largest proportion of land owned by Cimenterie Nationale in the vicinity of the quarry today, after one farmer sold hundreds of thousands of square meters of moderately productive, hard-to-grow white soil agricultural lands.[8] The small amount (“mere piasters”) received by the farmer allowed him to improve his living conditions in a town that didn't benefit from government services until the early 1960s.[9]

In the absence of any legal control to deter its activity and production, the company expanded its quarry throughout the lands it owns, causing the deterioration of the productivity and value of neighboring lands. At the same time, the company was accumulating other properties strategically, by besieging plots it did not own, effectively isolating them into islands amid the vast expanse of the quarry. “I had land in Badbhoun; about 2000-3000 sqm,” says a farmer from Kfaraakka. “I sold it to the company about fifteen years ago for four or five dollars per [square] meter. I had to, because the companies were digging and surrounding the lands there.” With agriculture declining as a source of livelihood, the majority of landowners sold their property for two main reasons: to educate their children and to cover medical bills.

Today, the Badbhoun quarry takes up a quarter of the town’s territory. It spans over one square kilometer of mountainous land. In certain parts, the company has lowered the land level to below sea level in certain parts. In others, it has altered wind and water flows. Most of the plots in and around the quarry (88.5 percent) are owned by the Cimenterie Nationale. In fact, for every three square meters of private property in the town, the company owns over one square meter. It has only quarried part of its lands so far.[10]

The Kfarhazir quarry is located a few kilometers from the Badbhoun quarry. In December 2018, the two main plots—where the larger part of the Holcim Liban quarry stands—were being sold, and no other information was available about them. The Sharikat Al-Mutajara Bel Ikar[11] owns most of the remaining quarried lands, in addition to two large, unquarried, adjacent plots, totaling over 520,000 square meters in and around the quarry, all bought between 1999 and 2010. For comparison, this is twice the area of the AUB campus.

Cimed Mining[12] owns the largest plot in the town (over 100,000 square meters bought in 1999[13]) and has only partly quarried it so far. These large plots stand out from the cadastral fabric of the town, which is tens and hundreds of times smaller and reflects the scale of residential and agricultural land-uses. This disparity suggests a pattern of land accumulation and pooling, especially since Koura did not know feudal landowners in its history, and its agricultural lands are known to be scattered. The third major owner of the quarried lands is the Sharikat Al-Turaba Al-Arabia[14] (55,000 square meters in 1997). In comparison with the Badbhoun quarry, what is worth noting in the Kfarhazir quarry is the multiplicity of its ownership, and the ongoing, vast real-estate transactions continuing to this day. Large and Small individual owners also owning plots in the quarry, the land is invested without being owned by a single entity as is the case in Badbhoun.

The Power of the Companies: Who Won the Battle over Land Zoning?

The purchase of plots by the cement companies was the first step to control the land and its resources. The next step was to prepare everything necessary for them to use the land whenever and however they like. Particularly important was their attempt to create quarries in places where they are prohibited.

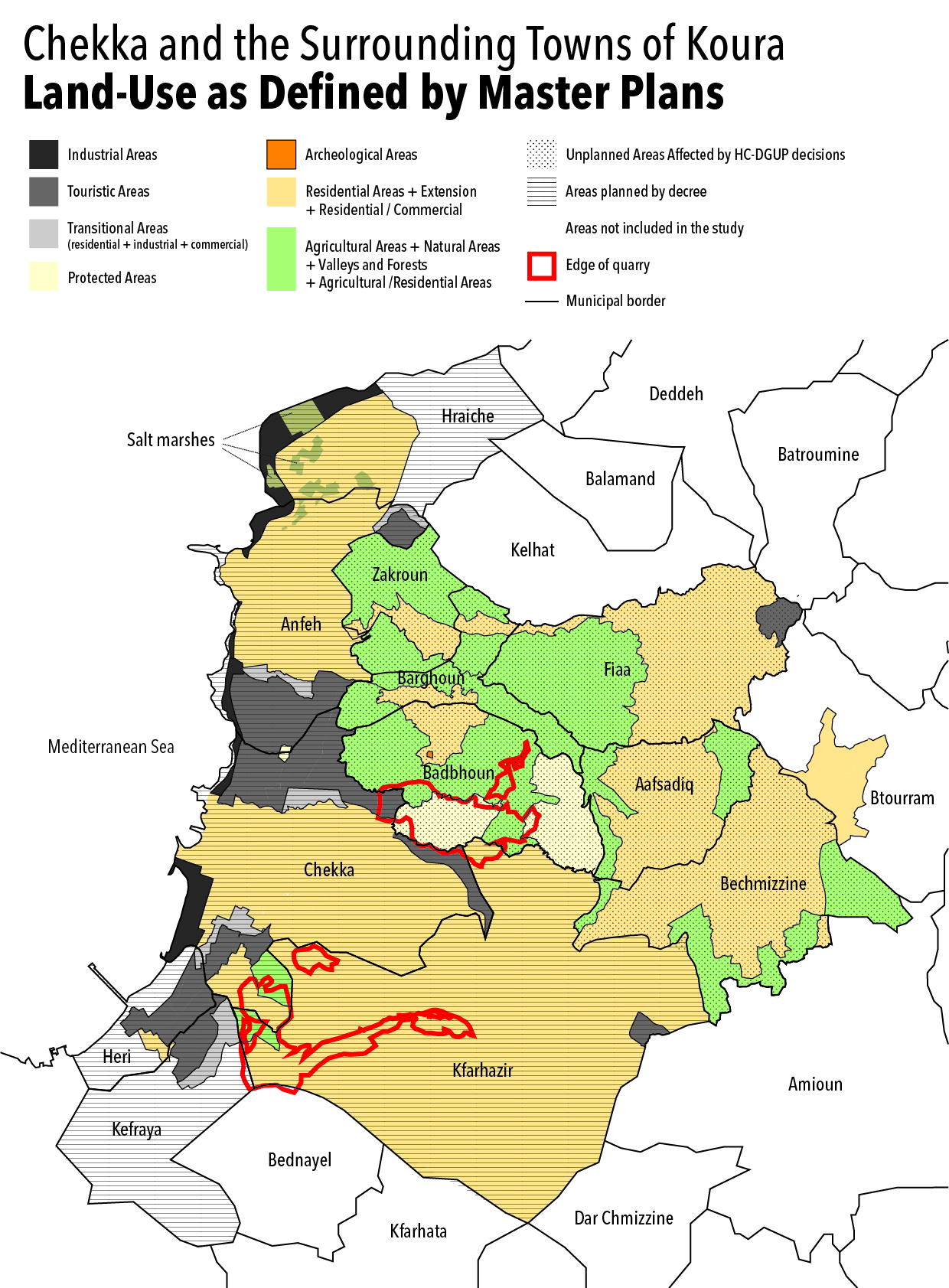

Upon inspecting the land zoning maps of Chekka and a number of Koura towns, we notice a “patchwork” of zoning types that are not necessarily logical or compatible, especially when looking beyond the borders of each individual municipality. On the one hand, industrial zones are haphazardly scattered in many areas (as if a fait accompli had been imposed) without sufficient buffer or transitional zones between them and the residential or green areas. On the other hand, we know that large expanses are used for agricultural purposes while master plans continue to zone them otherwise. This is the case of Kfarhazir, where agricultural lands are classified as “residential” in their majority. Perhaps this characteristic or analysis is not specific to the Koura region, and is common practice in urban planning across all of Lebanon. But what is noteworthy here is that, in addition to this, there are about two and a half million square meters of quarries on land not allocated for that.

Returning to the map, we see that the Kfarhazir quarry is located within an area zoned as residential, according to its master plan issued decades ago. The quarry became operational in the past ten years after many land purchases in 1999 and 2018, as previously mentioned. These quarries were illegally licensed, prompting the Kfarhazir municipality to issue a July 2016 decision

to categorically reject the amendment of zoning or land-use in plots within its jurisdiction, except by request and approval from the Kfarhazir Municipal Council, since the unrestrained dredge of lands is increasingly generating dust that has a severe impact on humans and plantations.

In August 2018, another decision was issued by the Kfarhazir Municipal Council to immediately stop all work in the quarries of Cimenterie Nationale and Holcim on the outskirts of Kfarhazir, subject to liability. Before the decision was issued, the Kfarhazir municipality formally requested both companies in to submit any official permit they had secured to set up quarries in their territories. The companies answered in writing that they had no permits, and that Holcim had applied for a permit in 2016 but had not yet received an answer from the relevant authorities.[15]

The other quarry we see on the map is located in Badbhoun. It has a more complicated story with more severe consequences. In May 1997, the Council of Ministers issued an unprecedented decision declaring the adoption, allocation, and zoning of the entire town of Badbhoun as a special area for the quarries of the cement companies for a period of ten years. Badbhoun was still an unplanned town, meaning that it had never been addressed by any master plan to guide its land use. Thus, this ministerial decision allowed the violation of an entire town and put its land, air, and homes at the mercy of quarries—with the stroke of a pen.

Activist Lamis al-Ayoubi explains that the quality of the soil in Badbhoun is very suitable for the work of cement companies. When the companies began excavation in the town, they had envisioned benefitting from the soil for one hundred years. Over the years, Badbhoun suffered from quarry dust, theft of its water, and the destruction of its homes. About forty percent of the town’s surface area has become mere raw material for the company. Ten years after the first decision, the Council of Ministers extended the 1997 decision for another two years. This date coincided with widespread action by local groups and civil society organizations in Koura, who felt that they could no longer remain silent. As of 2007, the pace of movements, sit-ins, petitions, press conferences, and open letters to government officials from various sides increased. Perhaps due to pressure from local communities, and with the impending expiration date of the ministerial decision, the Directorate General of Urban Planning (DGUP) decided to plan Badbhoun and the surrounding towns (Zakroun, Barghoun, and Kelhat) for the first time in their history. The study was completed and the master plan was issued by a decision from the Higher Council in 2011. The plan zoned the quarried area and its surroundings in Badbhoun as a “protected zone"[16] in order to reduce the impact of quarries and regulate the scope and expansion of their work. In an interview, a source at the DGUP (who asked to remain anonymous) says:

The area we classified as “protected” is largely owned by Cimenterie Nationale. “Protected” does not mean it is now a “reserve.” We did not prohibit the setup of quarries or facilities within it. It already contains quarries. But we recognized that the quarries can no longer expand and stretch arbitrarily. It is imperative to impose limits and environmental provisions for their expansion because the adjacent areas are dying. You can think of it as a buffer zone with conditions to prevent the company from turning all of its properties into quarries.

Cimenterie Nationale was not aware of this plan until 2015, after its cadastral registry documents revealed that its properties had been rezoned as a “protected zone.” A few months later, in February 2016, Cimenterie Nationale turned to the State Council to file a lawsuit against the state (Ministry of Public Works and Transport) demanding the revocation of the Higher Council's 2011 decision to define a protected zone in Badbhoun. Without any media coverage or support for the Higher Council’s urban planning decision, the State Council ruled in August 2016 to suspend the implementation of the Higher Council’s 2011 decision that effectively plans Badbhoun.[17] “After the master plan was suspended,” the source at the DGUP explains,

we were supposed to review it and submit another one, the DGUP asked the company to provide us with maps of their planned expansion, their activity schedule, and annual consumption, so that we can replan the area taking that data into consideration. They have not provided us with any of that to this day. The company is not cooperating, so we could not produce an alternative plan. The area remained unplanned, which serves no one but the company.

Companies have managed to circumvent urban planning, one of the many legal obstacles they were able to avoid. The story of Badbhoun and control over land in Koura may represent a real battle in which the roles of the state, the State Council, the municipality, society, and companies are complicated. In the end, the companies won the battle, which goes to show that cement companies in Lebanon are the most powerful in the Lebanese state.

[This article was written by Abir Saksouk-Sasso, based on research by Abir Saksouk, Monica Basbous, and Tala Alaeddine. It was translated into English by Claudine Farah, and originally published in Arabic by Legal Agenda.]

[1] In 1931, Archbishop Arida became Patriarch and before his death, he bequeathed his shares in the company to the Maronite Patriarchate. Reference: Boulos Sfeir, “A Brief History Based on References and Preliminary Documents: Bkerki Throughout its Historical Events 1703-1990,” Publications of the Institute of History at the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, 1990.

[2] Massoud Daher, Lebanon: Independence, Formula, and Charter, 3rd ed. (Beirut: Dar Al-Farabi, 2016) 69.

[3] According to a number of articles, for example, “Cement, Asbestos and Chemical Industries in Northern Lebanon” (Jawad Adra) & “Towards a Master Plan for Regulating the Coastal Industrial Zones” (Habib Debs), published in “The Lebanese Seashore-What's its Fate: Documents of the Symposium of the National Assembly for the Protection of the Seashore,” Order of Engineers and Architects, 16 March 1996.

[4] For more information on the subject, read the article by Obaida Hanna, “Death in Chekka... By Eternit,” Al Modon, 28 March 2017.

[5] Information on the political context was based on interviews we conducted during November and December 2018 with Koura residents, particularly with engineer Fares Nasif. It should be noted that there was a conflict between the Marada Movement and the Kataeb Party concerning cement revenues, according to the book by Abdullah Haj Hassan, The History of Resilient Lebanon in One Hundred Years 1900-2000 (Dar al-Walaa for Printing, Publishing, and Distribution, 2008).

[6] Decree 8803\2002 specified areas for the establishment of quarries.

[7] The agricultural plain between the towns of Amioun, Bishmizzine, and Kfarhazir.

[8] Wheat, barley, and cereals were intensively cultivated in Badbhoun, until the late 1960s.

[9] Jawad Adra, “Cement, Asbestos and Chemical Industries in Northern Lebanon,” in The Lebanese Seashore-What's its Fate: Documents of the Symposium of the National Assembly for the Protection of the Seashore (Order of Engineers and Architects, 16 March 1996).

[10] The second and smallest owner is Davico Real Estate, which owns 7.3 percent of the properties, bought between 1985 and 1992.

[11] The company was registered in 1973 and is owned with equal shares by Ghassan Hajjar, Ibrahim Abdel Nour, and Rebeka Ibrahim Abdel Nour.

[12] The company was registered in 1997 and the majority shareholder is another company under the name Cimed Holding SAL which in turn is owned by shareholders Kamil Nicolas, Natalie El-Khoury, Nadine El-Khoury, Hasib Eid, Charbel El-Khoury, Alexander Boury (majority shareholder), and Colette Abi Rached, based on the Commercial Register at the Ministry of Justice.

[13] Five times the area of ABC Verdun.

[14] In English, the Arab Cement Company.

[15] Interview with George Inati, November 2018.

[16] Protected Zone L: All permits within this zone are subject to prior approval by the Higher Council for Urban Planning.

[17] In principle, the decisions of the Higher Council for Urban Planning become ineffective after three years as of their issue date, unless they are issued by a decree within that legal period. But in practice—and this is indeed the position of the concerned public administration—they remain effective even after the expiry of the three-year period, in order to avoid legislative vacuum when the region is not already planned. For more information on this subject, read the article by Public Works Studio: “The Directorate General of Urban Planning: Arbitrary Practice Between the National Master Plan, General Master Plans, Exceptions, and Decisions,” The Legal Agenda, 26 February 2018.