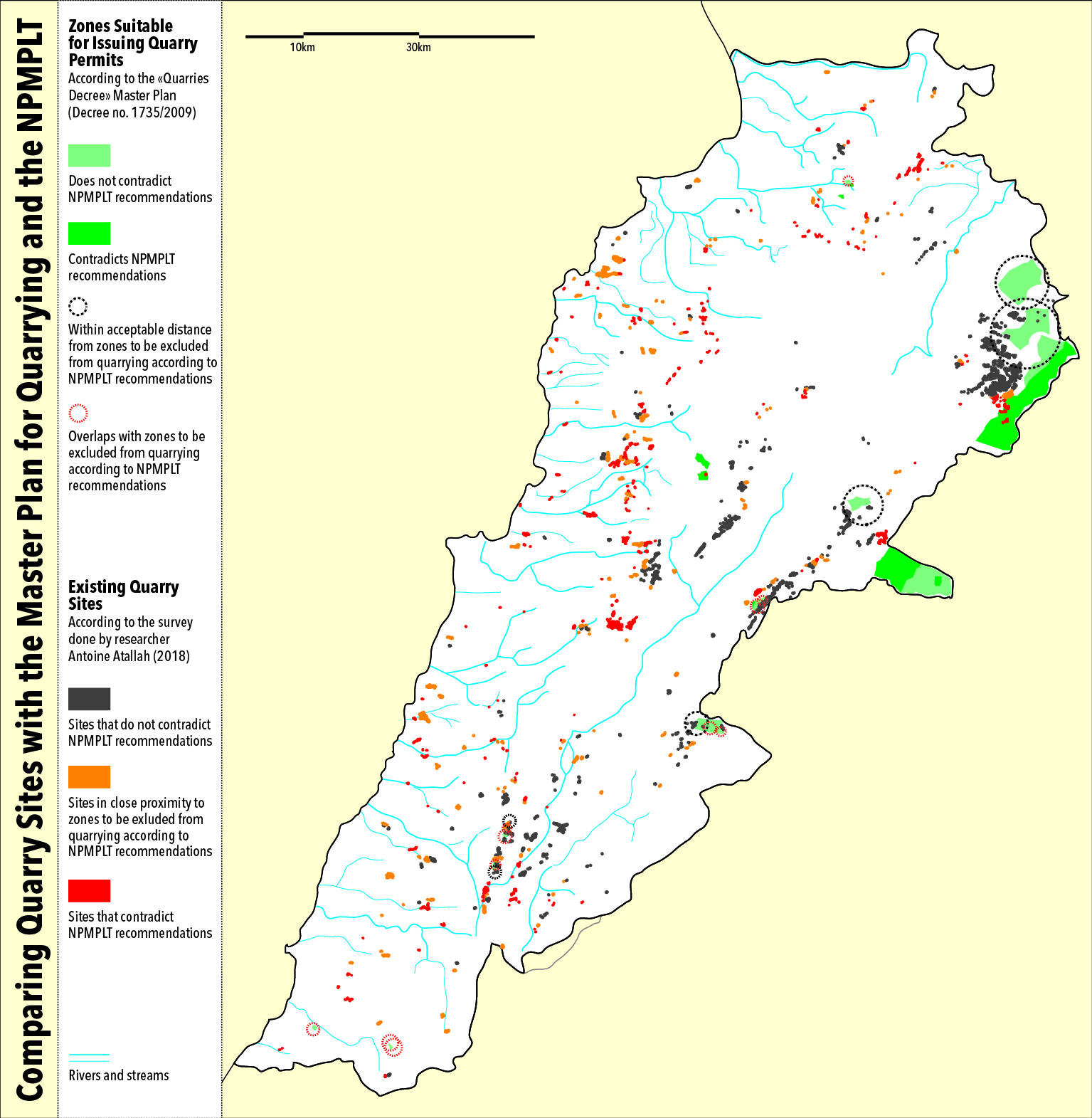

According to a 2008 study, between 1996 and 2005 the number of quarries in Lebanon rose from 711 to 1278. In 2005, 21.5 percent were in forests and fertile lands, 32.4 percent were concentrated in scrubland and grassland, and 3.2 percent were located in urban areas. This is a clear violation of resources, natural landscapes, and people’s health despite the legal guidelines and conditions that regulate the licensing of quarries. And yet, most existing quarries are located on sites that conflict with both the National Master Plan for Quarries and Stone Crushing Sites and with the recommendations of the National Physical Master Plan of the Lebanese Territory (NPMPLT).

Quarry Planning and Regulation Across Lebanese Territory

Until 2002, the regulation of the quarry sector lacked any geographical dimension. Instead, it was simply regulated through a series of conditions, which the administration rarely worked to enforce.

The first map that identified areas designated for the establishment of quarries was issued by decree 8803\2002. According to a source from the Ministry of Environment (MOE), the Council of Ministers set this National Master Plan for Quarries based on a study carried out by the consulting firm Dar al-Handasah in the 1990s at the request of the Directorate General of Urban Planning (DGUP), which identified twenty areas suitable for quarrying. The Council of Ministers selected four of these areas for the master plan, without consulting the MOE, and without any clear criteria or justification for how the sites were chosen. However, when we examine this map, we find that the sites have the following characteristics in common: they are all located in the largest district of Lebanon (Baalbek), where the population density is low; they are close to the Lebanese-Syrian border; and they are far from major cities.

Then, in 2004 and 2005, the MOE conducted a study to identify eleven additional areas for the decree’s master plan. This was done without consulting the concerned municipalities and in the absence of the NPMPLT recommendations, since the Quarries Master Plan was amended in 2009 (i.e., two months before the NPMPLT was issued by Decree No. 2366/2009). To determine these additional areas, the ministry adopted its own set of criteria: distance from urban areas, stormwater drains, natural reserves, schools, places of worship, seashores, and environmentally sensitive areas. Although the two studies were conducted in the same time period (presupposes that field data did not change radically between the two studies) and although their criteria are similar, the resulting maps present many contradictions.

In view of Decree 8803/2002 and its amendments, it seems that the public administration's approach to the territory is an abstract cartographic gaze that disregards details and daily life, ignoring complexities such as the existence of rural dwellings, agricultural plots, and forests within parts of the plan—most notably the towns of Tufail, Ain El Jawza, Ain Bourday, Arsal, Ras Baalbek, and Qaa in the Baalbek District; the town of Ain Ebel in the Bint Jbeil District; the towns of Aita al-Foukhar and Yanta in the Rashaya District; Deir El Ghazal and Qousaya in the Zahle District; the town of Kfour al-Arabi in the Batroun District; and all the natural and agricultural areas within these towns. The chronic scandals of the quarries operating in Koura have time and time again revealed the state's collusion with quarry operators. As cement companies evade legal requirements, and in the absence of control on production, there are no guarantees that quarries, even if established within legislated areas, will not expand and completely wipe out neighboring villages and mountains.

In addition, when the NPMPLT was issued in 2009, about half of the already-legislated areas for quarrying were in conflict with its recommendations. The provisions of the NPMPLT include it superseding all previous legal texts. Yet the National Master Plan for Quarries (issued two months prior to the NPMPLT) wrongly remains the reference for quarry regulation to this day. In some areas, quarries are a clear waste of the resources and potential of towns and villages, as the National Master Plan for Quarries allows their establishment near areas the NPMPLT considers to be of national importance and thus requiring protection. Most notable in this respect are the adjacent agricultural Bekaa Valley, areas that offer unique landscapes such as the Anti-Lebanon Mountains, uninterrupted valleys, and ecosystems such as the Bekaa Valley stretching between Mount Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon.

Furthermore, the unrevised National Master Plan for quarries completely ignores and avoids non-compliant and unlicensed quarries, as well as those outside the legislated areas. Effectively, the National Master Plan for Quarries relied on a simplified map which did not include existing quarries, as though their absence were sufficient to organize the sector anew. As a result, it did not propose any measures to address pre-existing sites, reduce their impact, or absorb them into new arrangements. This simplification demonstrates superficial and illusory legislative work that lacks any real intention to offer effective regulation or sustainable guidance.

Based on a survey conducted by architect Antoine Atallah[1] in 2018, Public Works Studio produced a map that shows the contradictions between the NPMPLT and the National Master Plan for Quarries. It illustrates the overwhelming number of existing and abandoned quarries in Lebanon that violate both the provisions of the quarries decree and the recommendations of the NPMPLT. Few of these quarries have permanent “temporary permits,” and when a quarry does have a permit, it is often issued by authorities that have no jurisdiction over the sector according to the current decree (e.g., the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities). Evidently, they are obtained through political or economic clout, without going through the steps specified by Decree 8803/2002 and without complying to its conditions. Therefore, it is safe to say that this sector operates outside any recognizable law.

Why Are Quarries Located Outside the Legislated Areas?

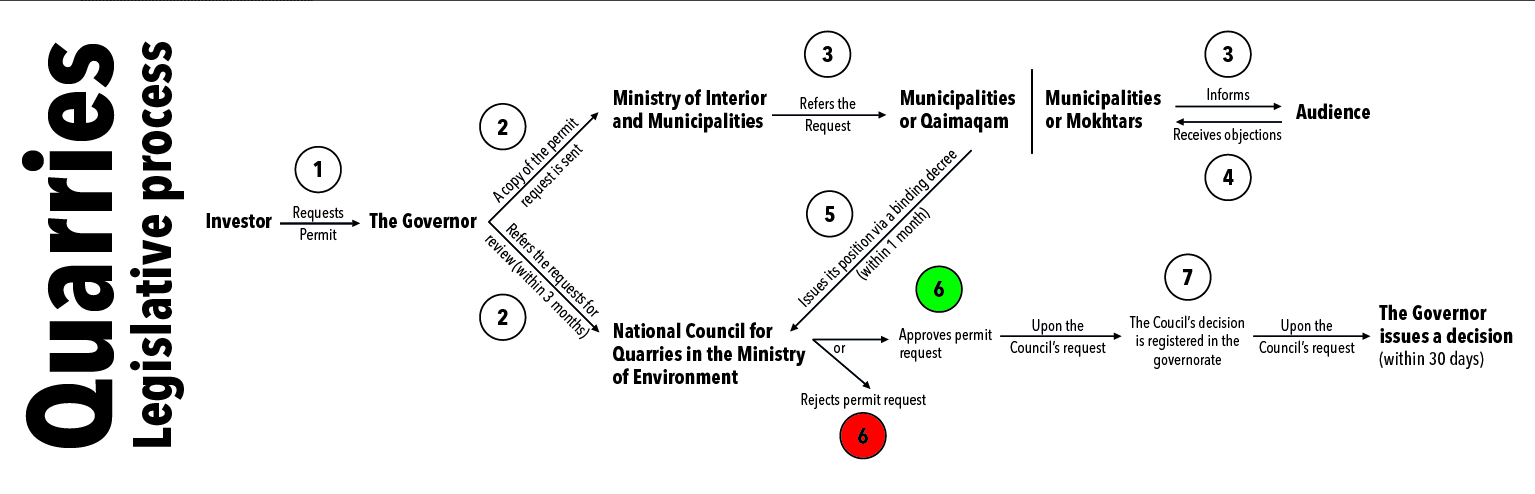

Between 2002 and 2009, only four applications for quarry permits were submitted within the designated areas. Three of them received approval, while the fourth was rejected after the municipality of Aita al-Foukhar (Rashaya District) declined it (see diagram “Quarries: Legislative Process”). According to a former MOE employee, there are two overarching reasons for the minimal number of permit applications in the areas allowed by the National Master Plan for Quarries: first, the geographic distance of these areas from the coast, which increases the cost of transport and export compared to illegitimate quarries; second, the lax implementation of the law on quarries located outside allowed areas, particularly those closest to the coast. Both these factors converge to produce an imbalanced and unfair competitive relationship in favor of the infringing enterprises—at least as long as violations remain ignored.

Nothing changed after adding another eleven areas in 2009, when only a small number of new permit applications were submitted. At times, municipalities themselves were behind the rejection of the application. For example, the municipality of Yanta (Rashaya District) does not grant any quarry permits even though there is an area designated by the decree within its jurisdiction. The same goes for the municipalities of Majdal Zoun (Tyre District) as well as Tayri and Ain Ebel (Bint Jbeil District). The municipality of Qousaya-Deir al-Ghazal (Zahle District) requested the removal of the entire area designated by the decree, but this requires the Master Plan for Quarries to be amended by the Council of Ministers. These examples demonstrate the importance of involving local authorities in regulatory processes at the national level, especially for projects and facilities that consume finite resources and affect public health and safety, the environment and the sustainability of natural resources.

The decree “Strategic Environmental Assessment for Public Sector Policies, Plans and Programs” (8213/2012) was an opportunity to regulate the sector, including its informalities, but the decree had no retroactive effect on existing quarries.

Key Factors in the Sector’s Unruly Expansion

The authorities’ failure to control production, enforce conditions, and impose penalties on violations in accordance with Decree 8803\2009 is only one element in the broader dynamic. The motives undergirding the lack of effective oversight of the quarries sector becomes evident when we look at national economic policies and their local repercussions.

In 1993, the government decided to ban the import of cement. This had two important effects. On the one hand, it led to a market monopoly by three cement companies in Lebanon (Cimenterie Nationale–al-Sabeh Cement; Lebanese Cement Company–Holcim Liban; and Ciment de Sibline sal). On the other hand, it encouraged the sector to spread to meet the needs of the country and the region in (re)construction. Domestic activity in the construction sector, including land reclamation projects, has been a key factor in the sector’s inflation.

Even today, in the absence of any policies that support the agricultural sector and protect natural resources, we are witnessing the depletion of rural resources by quarries which are destroying agricultural economies, disfiguring landscapes, harming inhabitants, and threatening to wipe out entire villages.[ii] The declaration that Lebanon would be a major partner in the reconstruction of Syria has intensified the stakes. This can be clearly seen in the Kfarhazir and Badbhoun quarries in Koura, where historic local economies such as olive cultivation have already been weakened by allowing and facilitating the importation of olive oil since the late 1990s.[iii]

Furthermore, there has been no study to reconcile the master plan and terms of the quarry decree with the NPMPLT. According to a source at the Ministry of Environment, the Council of Ministers (headed by then Prime Minister Najib Miqati) issued Decision No. 50 (of 7 March 2012) to form a ministerial committee tasked with reviewing the national plan for quarries. The committee met, studied the situation, and submitted its proposal. But it remained “in the drawer.” In 2014, the Council of Ministers (headed by then Prime Minister Tammam Salam) issued Decision No. 33 (of 9 May 2014) to form a ministerial committee to draw up a new plan. This committee never held any meetings. More recently, the Council of Ministers issued Decision No. 102 (of 4 May 2017) to form a governmental committee to follow up on the study of quarries and stone crushers. To date, this committee has met only once. On top of all of this, and despite Decree 8803/2009 and the MOE’s Decision No. 48/1 (25/06/2009) setting clear conditions for rehabilitation within both running and abandoned quarries, the sight of eroded mountains and landscapes are witnesses to the administration’s failure to enforce these conditions.

The absence of a unified legal-regulatory framework; failure to enforce legal conditions, regulations, and penalties; the non-regulation of existing quarries; and economic policies that encourage quarrying and eliminate alternative economies—these are some of the factors that have shaped the plagued landscape that characterizes Lebanon today. Investing in the quarry sector appears to be lucrative in the short term, and devoid of any repercussions for practices that create harmful and destructive effects on public health, the common good, and shared resources on the long term.

[Written by Monica Basbous. Research team: Abir Saksouk, Monica Basbous, Tala Alaeddine. Article translated by Claudine Farah, originally published in Arabic on the Legal Agenda]

[i] Antoine Attalah is an architect and designer, active member of civil society in Lebanon, and advocate for public transport, heritage, and public spaces.

[ii] This is the case of Badbhoun in Koura, where the quarry takes up more than a quarter of the village area.

[iii] In 1998, the Agreement to Facilitate and Develop Trade Among Arab States, which Lebanon joined in 1985, was implemented. The agreement frees trade between Arab countries from various fees and restrictions, which allowed the import of olive oil from Tunisia and Syria to the local market.