"All along the watchtower, princes kept the view

While all the women came and went, barefoot servants, too.

Outside in the distance a wildcat did growl

Two riders were approaching, the wind began to howl."

Bob Dylan, All Along the Watchtower

As many articles like this will certainly remind us that this year, 2013, commemorates two decades since the signing of the Oslo Declaration of Principles between Israel and the PLO. The endurance of what was supposed to be a five-year interim agreement is likely to be the subject of growing scrutiny from policy-makers, academics, international organizations, donors and Palestinians more generally. While such a retrospective is predictable if nothing else out of nostalgia for the euphoria of peacemaking in the 1990s and as material for today’s media mill, some of the central pillars of the Oslo framework are increasingly challenged on the ground.

True, Israeli-Palestinian security cooperation appears comparatively solid and unassailable—having been the sub-rosa of the Oslo arrangements from an Israeli perspective and for this reason Israel has made it work. Nevertheless, it is frequently tested at flashpoints with a restless population and the continued assertion of the Israeli security-first logic. But the “interim self-government arrangements” and the political system that Oslo created seem to have lost much of their credibility for a largely passive, if discontented, Palestinian public weary of unfulfilled promises of liberation and statehood. Meanwhile, a break-away “self-governing” political system has taken hold in the Gaza Strip and instead of one Palestinian Government, we now have two.

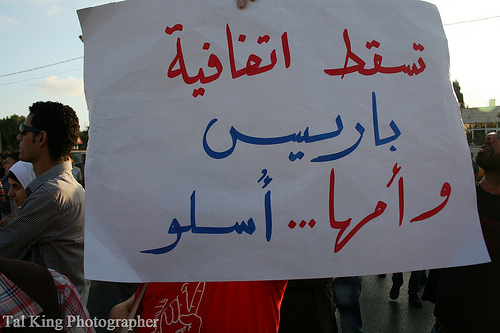

The other key premise - and promise - of Oslo was the potential of Israeli-Palestinian-Arab-international economic cooperation, which would in turn deliver prosperity to the Palestinian people. The September 2012 popular protests throughout the West Bank rudely repudiated these assumptions, perhaps always naïve and only recently subject to critical political assessment. Among the targets of popular ire was the Paris Protocol on Economic Relations, annexed to the Oslo agreements. Many demonstrators identified the Protocol as a key instrument in the Israeli system of colonial control, occupation, and denial of sovereignty. The calls for its abrogation were explicit, and to make the point its effigy was burnt in some protests.

[Image of a protest in Ramallah calling for the ending of the Paris Economic Protocol. Image by Tal King.]

However, the broader popular contestation did not focus so much on the Protocol or Oslo frameworks per se as on those politicians managing them. In response, Prime Minister Fayyad reminded his critics that he was not responsible for negotiating the Protocol and that his government faced a sub-optimal situation in implementing it, even while insisting on its continued suitability as a framework for the Palestinian economy. But popular mobilization was unable, beyond newspaper headlines and op-eds, to prompt a serious public or policy debate on the pros and cons of the Protocol and its continued application. While a growing critical chorus (not only Palestinian) has emerged over the years, the only party on record that is still unwilling to reconsider or re-negotiate the Protocol is Israel.

From the manner in which popular concern about the Protocol has receded from the political agenda, it would appear that expert and popular discontent with the Israeli-Palestinian economic relations has yet to go beyond scratching the surface of this issue. Over twenty years, that relationship and future options have been repeatedly debated, if rarely challenged, with little change in the status-quo, indeed with a major degradation in economic conditions as compared to the “golden era” of cooperation in the flush of the post-Oslo euphoria. Furthermore, it is likely that the balance of economic and political power and experts wedded to the concept of the two-state solution (on both sides of the equation) cannot countenance “opening” the Paris Protocol, which is an Annex to the broader Oslo framework, without putting the whole package into question. The more tangible issue of the PA fiscal and public sector salary crisis has recently revived expert comment and public mobilization. The debate is currently focused on the twin deficit created by shortfalls in donor aid and, more systematically, by PA public revenue dependence on the goodwill of the occupation authorities, as if these could be treated in isolation from a re-examination of the Protocol or Oslo.

The economic problems that have evoked popular contestation (taxation, inflation, employment, salaries, wages, poverty, and public utility provision, to name but a few) have been amenable only to stopgap remedies. There is no sustainable solution at hand. And the intrinsic link between current economic woes and the Protocol will understandably continue to assert itself and demand serious attention, prompting-- if nothing else-- an effort to rehabilitate the Protocol in practice, if not in perception. So it should come as no surprise that Palestinian and international policy circles are again posing questions as to whether and how the Protocol can be modified, amended, enhanced, or otherwise “reconsidered” as the appropriate framework for Israeli-Palestinian economic relations, indeed for the future development of the Palestinian economy and of an independent state of Palestine.

[Image of a protest in Ramallah calling for the end of the Paris Economic Protocol on 1 October 2012. Image by Tal King.]

As two observers and practitioners who have followed the (mis)fortunes of the Protocol since its infancy, we would like to offer our own candid contribution to exposing it for what it is today.

We recognize that amidst the current conventional wisdom about the collapse of Oslo or the PA, renewing the arguments in favor of scrapping the Protocol might seem like flogging a dead horse.

But efforts to rehabilitate the Protocol (or save Oslo) should be expected from different quarters. These efforts may be motivated for example by the good intentions of some European or Israeli liberal think-tanks in the belief that the two-state solution can be salvaged by prolonging economic peace and repackaging the Protocol. Israeli colonial planners might also be interested in a new version of Paris since its original elaboration has withstood Palestinian resistance, which continues to be ineffective, even if vocal. International organizations and major donors with a stake in the ultimate predominance of the neoliberal experiment that Oslo/Paris constitutes will also see more virtue in sticking with the Protocol. PA policy makers and business interests might also entertain reforming the Protocol, still believing, despite all evidence to the contrary, that it offers the optimal political and economic framework for Palestinian development. While political stalemate might discourage the PA from actively pursuing a re-negotiated, improved version of the Protocol, any resumption of a political process would demand a parallel economic process, especially given the pending, September 2012 PA request to Israel to “re-open” the Protocol.

We offer here our own selection of Frequently Asked Questions and answers about “fixing” the Protocol, to which we suspect that many concerned parties are today urgently searching for answers. We would like to save some time and effort of those who seek to breathe new life into the moribund Protocol. Even better, maybe this foray can prompt those concerned to ask the right questions about how to secure Palestinian economic security and development aspirations, instead of trying to optimize a dysfunctional and inherently imbalanced Israeli-Palestinian “economic relation.”

FAQ 1. Are the gaps and shortfalls of the Protocol itself and in its implementation really insurmountable?

Yes. Fiscal leakage is widely recognized by all international organizations, and has long been the subject of Palestinian complaints, as the biggest weakness in the Protocol’s fabric. This is due to a cumbersome, costly, and opaque “clearance” mechanism that leaves all the information and levers in the hands of the Israeli Ministries of Finance and Defense. A forthcoming UNCTAD study confirms over 200 million US dollars worth of documented annual leakage because of weak customs control, antiquated clearance arrangements, and tax avoidance that the Protocol has made possible. This implies a cumulative amount since 2005 that is equivalent to the fiscal deficit the PA has run up since 2001. The latter has reached around 1.5 billion US dollars. While Palestinian-Israeli “technical” discussions in 2012 reportedly addressed new procedures to capture leaking fiscal revenue, Israeli sources have never admitted more than seventy million US dollars annual lost PA revenue. Thus any attempt to secure foregone revenue would most likely be a Sisyphean task.

On a conceptual and economic policy level, the absence of a national currency (and hence, lack of resort to macroeconomic and exchange rate policy) is one of the Protocol’s most enduring weaknesses. Trade diversion to Israel (instead of creating new trade with other partners) is another chronic burden on the prospect for building a strong Palestinian economy. Most significantly, the tariff structure of Israel is one appropriate for an advanced, industrialized, and increasingly outward looking economy. But the tariff structure required to rebuild the Palestinian economy and allow it to stand on its feet so it can "compete" implies a very different stance towards external trade than that which suits Israel. The existing quasi- “Customs Union” (CU) between the Palestinian and Israeli economies does not allow such differentiation. It remains, as it has always been the least attractive option from a Palestinian developmental angle. It remains, as it has always been, the optimal arrangement from the occupiers’ point of view as it allows for maximum capture of markets, revenue, and security interest of the colonial power.

Even the World Bank agreed with the Palestinian position when, under the pressure of the Intifada and Israeli separation measures, both were emboldened in 2002 to call for abandoning the CU with Israel and opting for a separate trade regime. But the PA has in recent years reaffirmed its commitment to the Protocol. It has also renewed Panglossian arguments which were fashionable in the 1990s that the CU is the best possible option, effectively bucking all the expert wisdom. Since then, the Bank too has reformulated its position and reverted to supporting the counter arguments of Israel and a small minority of Palestinians that an autonomous trade regime was the least appropriate option. The shift in positions is a function of different assumptions; however, the facts on the grounds continue to prove the inoperability of the CU for the Palestinians and the impracticality of a FTA under occupation and colonisation.

FAQ 2: Are there any lessons that can be learnt from amendments made to the Protocol since it was first agreed in 1994?

Not much. No mutually agreed amendments have ever been made to the Protocol, even though certain items were added and quotas were raised on lists of goods that the Protocol allowed import from Arab and Islamic countries. This did not require amendments as such and the Protocol remains on paper very much as conceived twenty years ago. The PA never pursued the areas where it could have been amended. The one exception was at Camp David in 2000 when the chief Palestinian economic negotiator and former Minister of Economy, Maher Masri, succeeded in obtaining an agreement in principle with the Israeli Finance Minister on abandoning the CU in favour of a Free Trade Area (FTA). This would not have meant an amendment to the Protocol but rather its abrogation. But the key benefit to Palestine of an FTA (not to mention a CU), namely free labor movement, was not something Israel was willing to agree to then (and hardly today). This rendered the idea of an FTA unattractive from the Palestinian viewpoint and if nothing else, should rule out a continued CU.

By 2002 and in the face of the Israeli separation policy, Minister Masri and the PA were actively reassessing the costs and benefits of Palestinian separation from the Israeli economy. For a few years the PA sought actively to build new trade channels to the Arab east and move towards a Most Favoured Nation relation with Israel. This is also known as non-discriminatory treatment (i.e. no negotiated bilateral trade/economic agreement with Israel with any greater preference than accorded other trade partners). But as the intifada ground to a halt and Israeli control was reasserted, Palestinian hopes for breaking out of the CU stranglehold receded. Thus, a discussion today about an “enhanced” CU lives up to that old definition of insanity: doing the same thing again and again and expecting different results.

FAQ 3: The Protocol established a Joint Economic Committee (JEC) as a mechanism for supervising and arbitration, while other mechanisms discussed other trade and economic issues: can’t that serve as a conduit for resolving differences?

No. The JEC was not designed or used as a mechanism for trade arbitration, since it was predicated on a five-year interim self-government period that was treated by both parties as one best spent managing the new quasi-CU arrangements, however imperfect, rather than building a correctly functioning CU. [Read more…] Essentially, Israel used the JEC as a forum where the PA could raise implementation hiccups and, depending on how urgent they were or how accommodative Israel was at any moment, some “treatment” would be decided. Follow-up usually entailed the establishment of a “new” JEC sub-committee at the technical level that met for months before agreeing or not on any given step, incrementally, in a piecemeal and discretionary manner responding to commercial demands as they arose, not as part of any strategic economic cooperation process. By the end of the 1990s, the JEC was still meeting. After the Wye River Accords of 1998, its image was slightly revived with approval of some extensions to lists A and B that the PA had demanded for several years. But increasingly the JEC became dominated by the PA Civil Affairs Ministry and its concerns and interests rather than Minister of Economy and Trade (or Finance), which should have directed PA interaction with the JEC.

Thus, Israel succeeded in manipulating the JEC as another of the "bilateral" instruments for prolonged occupation, drawing PA officials into a collaborative logic instead of a state-building process. Since the 2000 intifada, the JEC at the Ministerial level has been defunct, except for one brief, abortive meeting in 2009. Some of its sub-mechanisms persist to manage daily affairs, but largely as implementation mechanisms for Israel to inform the PA of its due tax clearance revenues, changes in Israeli tariffs or laws, and other one-way "coordination." Simply put, the JEC is clinically dead. There is no need for life support, much less resurrection, through wishful thinking.

FAQ 4. Given the impact on the Palestinian economy and on trade and clearance revenue of the Israeli disengagement from Gaza, and with the possibility of opening the borders with Egypt, could the reestablishment of PA presence at Rafah be a step towards a Protocol Version 2?

No. If anything, the new circumstances in Gaza spell the de facto, if not de jure, termination of the Protocol in that part of Palestine. As part of its broader colonial strategy of dividing the Palestinian people and ruling each under the appropriate regime, the Gaza disengagement provided a suitable way for Israel to shed itself of the economic "burden" of having to support the "hostile entity" that Gaza was designated. Within a few years of disengaging from direct occupation, Israel also deleted the Gaza code from its customs book, symbolizing its capacity to unilaterally cut economic links to such an “enemy territory.” The PA-Hamas divide since 2007 deepened that cut and played into Israel’s strategy. The two territories became separately fiscally and commercially dependent on Israel or on donors and humanitarian relief, each through different channels and on different terms that Israel mediated and decided. This has had a devastating impact on the prospects for realizing the principle of Oslo that the West Bank and Gaza Strip are an integral economy and geographic entity, not to mention rendering the economic viability of statehood a chimera.

FAQ5: Could bringing East Jerusalem (EJ) into the equation make Israeli-Palestinian economic relations more attractive to the Palestinians?

No. Such a prospect borders on the realm of the hallucinatory. As a forthcoming UNCTAD report demonstrates, the East Jerusalem economy finds itself in a world quite apart from the Palestinian and Israeli, economies to which it is linked. It is integrated into neither. At the same time, it is structurally dependent on the West Bank economy to sustain its production and trade of goods and services and for employment. It is forcibly dependent on Israeli markets whose regulations and systems it must conform to and which serves as a source of employment, trade, and tourism.

These paradoxical relations have left the East Jerusalem economy to fend for itself in a developmental limbo, severed from PA jurisdiction and subordinated to the Jewish population imperatives and settlement strategies of Israeli municipal and state authorities. Just as the economic growth pattern and overall direction of the Gaza Strip in recent years has veered in a distinct and separate direction from the West Bank, so has East Jerusalem’s economic trajectory diverged from that of the West Bank. These trends render the notion, enshrined in United Nations resolutions and the Oslo Accords, that the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, constitute a single territorial and legal entity null and void. Integrating East Jerusalem in a proven dysfunctional economic agreement would only further fragment its fragile economy and alienate its Palestinian population.

FAQ 6. Can the building of modern border terminals, bonded warehouses, and other facilities improve the flow of trade?

No. If the Israeli authorities have their way, soon all trade with the PA areas A and B of the West Bank will pass through sixteen “border crossings” that Israel is unilaterally establishing along the Separation Barrier. Israel intends to gradually develop these crossings into full fledged commercial trade terminals, in some cases linked to inland “bonded warehouses”. These arrangements are not sanctioned by the Protocol. They run against the very spirit of a CU. They constitute new realities following the security-first logic of the Barrier, which Israel justifies as de facto realities. They hark back to previous Israeli schemes, packaged in a more attractive form and rationalized by the need to trace “actual trade.” The PA may well be pressured to accept this proposition under the slogan of trade facilitation and capturing leakage. But in fact this would mean acquiescing to something that was resisted since the 1990s whenever Israeli authorities proposed inland "customs stations" which would not necessarily be on 1967 lines but dictated by Israeli settlement/roads/security lines in the West Bank. Beitunieh commercial terminal outside Ramallah was the first of such “stations.”

While more information should be revealed on recent Palestinian Israeli discussions on this complex issue, it should not be considered as an existing implementation mechanism of the Protocol. This rather implies a separate, new arrangement that would impose other changes that would effectively take matters well beyond the Protocol in terms of the effective trade regime in place. In case the Barrier borders, customs stations, and bonded warehouses are not going to be established along the 1967 borders, then it is incumbent upon the Palestinian side to examine whether continuation of the CU is reasonable.

One of the impediments to agreeing a FTA with Israel at Camp David in 2000 was how to control complex “rules of origin,” something that required border controls and customs capacity that the PA did not have then. If such border crossings/terminals (which are actually best termed “customs stations,” since they are not all on the borders) are now being planned, the PA will need sophisticated customs capacity to control and inspect, something that it could deploy fairly rapidly given the modernization and experience of PA Customs in the past decade. In such an eventuality, PA institutional capacity would be better applied to moving to an FTA with Israel, which would minimize the disadvantages of the Israeli-imposed trade infrastructure, while conferring benefits from new trade with other partners. Even Professor Ephraim Kleiman, the Israeli economist godfather of the “Palestinian “customs envelope,” believes today that this would allow greater Palestinian policy discretion in managing its trade with the rest of the world and eventually decrease Israeli domination of the Palestinian external trade sector.

FAQ 7. Can the UN resolution granting Palestine a non-member state status be a basis for strengthening Palestinian economic bargaining position with Israel?

Hmmmmm. Using rosy-tinted glasses to peer into the future, the only way that there could be any translation on the ground of the UN resolution and the subsequent transformation of the PA into the "State of Palestine" would be through political and economic reunification of the West Bank and Gaza. [Read more…] In such an eventuality, with a "State of Palestine" national government based in Gaza, it could apply a range of trade, fiscal, and even monetary instruments appropriate to governing the under the new circumstances. Israel unilaterally removed Gaza from the CU envelope and the area has demonstrated huge potential for trade with/through Egypt. A new growth trajectory, and a new narrative of Palestinian development under adversity, has emerged there that demonstrate other Palestinian options than the PA’s choice of a neoliberal economic model.

A move to establish an autonomous Palestinian trade regime in Gaza could be envisaged even while maintaining the PA self-government arrangements in the West Bank more or less in cooperation with Israel and without prejudice to the ultimate disposition of the rest of the occupied territory. In Gaza, a Palestinian currency could be introduced, providing a range of hitherto inaccessible macroeconomic policy instruments to generate growth and public revenues. Indeed, the longstanding Palestinian argument that the occupied territory constitutes a “separate customs territory” that renders Palestine eligible for membership in the World Trade Organization would receive a credible boost in such a circumstance. If economic policy duality is the price to be paid for political unity, then the Palestinian institutional capacities needed for such a complex strategic orientation would have to be mobilized within a new framework of “economic nationalism” that sheds the Oslo legacy of Israeli control and Palestinian subservience.

FAQ 8. Aren’t there any future options to renegotiate the Protocol, expand its coverage to Arab countries and involve international third parties?

No. Further trade or economic negotiations should not be pursued bilaterally with Israel, nor should they be focused on optimizing the Israeli-Palestinian economic relation. At best, in the context of WTO-sponsored negotiations, a future trade relation with Israel and all other countries could be discussed multilaterally as part of constructing a new Palestinian trade regime that protects its developmental interests and puts an end to Israeli trade and economic sanctions, which are manifestly illegal under international trade law. To the extent that it can, the "State of Palestine" should begin to act unilaterally to move beyond the Protocol (even while not explicitly having to repudiate it or Oslo) in any part of Palestinian territory that it can do so.

The only "improvement" that could be sought for current trade flows to the West Bank is full monitoring and capture of PA revenue leakage through new clearance mechanisms that do not entail in return any acceptance of the change in the legal and political status quo. Beyond that, any changes that the occupying power intends to impose (barriers, terminals, warehouses) that imply any "amendment" to the Protocol or other negotiated agreement should be avoided. Instead, all public and private sector efforts should be focused on breaking free of the Israeli stranglehold on trade, through for example, establishing a trade corridor to Jordan through Allenby, supporting viable import substitution efforts, and designing a new trade regime that responds to national economic security in all parts of the occupied “State of Palestine.”

[The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the PLO Negotiations Affairs Department or the United Nations secretariat.]