[All photos by Mohammad al-Azza.]

“We were joking,” said Mohammad al-Azza from his hospital bed, “but I couldn’t take the joke.” My husband and I had called and woken up our friend, a photographer and documentary maker, recovering after an Israeli soldier shot him in the face—and these were his first drowsy words after accepting our well wishes.

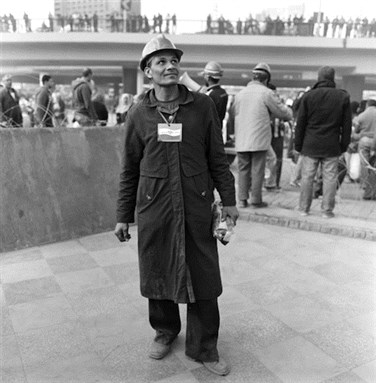

A day earlier, on 8 April, Mohammad was injured while photographing an Israeli raid into his community of Aida Refugee Camp—located on the outskirts of Bethlehem in the West Bank. The separation wall circles around two sides of the camp, and a military base is embedded in the wall at Rachel’s Tomb. Looking out Mohammad’s home window, one can see the wall perhaps a hundred meters away in each direction. From a community organization called Lajee Center, the eight-meter cement wall is even closer. As both a photojournalist and the director of the media unit at Lajee, one could say Mohammad was well positioned for his work. So when, on a calm afternoon, the soldiers left their base on foot to enter the camp, he simply stood up from his desk and began taking pictures from a second-floor balcony.

A soldier told Mohammad to stop shooting, but he told him he would not stop. “You’re shooting bullets. I’m just taking pictures.” But he retreated behind the door of the balcony, keeping it open just enough to continue to photograph. Youth gathered to protest the soldiers’ presence on their streets, and the soldiers began shooting tear gas and rubber-coated bullets. Mohammad continued to take pictures of the street below him from the balcony. About ten minutes had passed when he took one of a soldier pointing an M-16 rifle outfitted to fire rubber-coated metal bullets. A moment later this soldier looked through the scope on his rifle and shot Mohammad in the face from about ten meters away. The bullet shattered his cheekbone. As a friend helped Mohammad exit the building, the soldiers continued to fire at the door of the community center. In a lucky moment, they were able to escape to find a car to take Mohammad to the hospital.

There were two kinds of exchange between Mohammad and the soldiers. In the first one, soldier and photographer each used words. In the second, each used the instrument he had at hand. Perhaps for each it felt utterly natural. Certainly, Mohammad has taken many photographs of soldiers. Perhaps the soldier has shot many Palestinians. Surely he has been trained—militarily and in other regards—to shoot Palestinians.

I have known Mohammad, who is twenty-three years old, for ten years—as a family friend and later as a colleague in media production. Before he became known as a talented and intrepid photographer, he was known for his humor: for dead-on imitations of anyone and everyone; for eyebrows that laughed along with his smile. He brings his humor into his media work. Drawing on both the zeitgeist of cats on the Internet and the real life profusion of cats in the streets of Aida Refugee Camp, Mohammad produced a podcast about a cat wanting to take a walk beyond the wall. It features Mohammad’s convincing meows as well as his drumming to mark the cat’s stroll. The image accompanying the post shows a giant tabby positioned in front of the wall with a look of consternation. It is the kind of unexpected goofiness that feels like a gift in grim times, and it is quintessentially Mohammad.

Sometimes his humor is harder to detect. On 20 February, the Israeli army arrested his brother, Saed al-Azza, in a nighttime raid that left their house in shambles. After about a month, Saed finally had a court date. Mohammad and his mother were eager to see him. The evening after the court date, I chatted with Mohammad on the computer to ask how is brother was. He had not seen him, he said. Why not? He responded that the prison officials had forgotten to bring Saed! Of course my initial response was of outrage—how could such a thing happen? But reading again what he had written, I recognized that although what he was telling me was true, he had already turned this into a joke, a one-line political commentary on how military occupation works. According to a military courts’ annual report obtained by Haaretz in 2011, 99.74% of cases heard by the military courts end in a conviction. The actual defendant is so inconsequential to the legal proceedings that it was perfectly apt that he had been forgotten.

What does it mean that Mohammad called his own shooting a joke, hours after it happened? It is not funny at all for a man to aim a gun at another man who holds only a camera and shoot him in the face—perhaps killing him, perhaps taking his eye, almost certainly disfiguring him. So what was Mohammad getting at from his hospital bed?

Perhaps it was a joke about how Israeli soldiers talk. Palestinians may speak to them in words, but too often Israeli soldiers respond with bullets. Perhaps it felt like a joke that he, a Palestinian photographer, had tried to communicate with a soldier, even to make a pun about various kinds of “shooting” by telling the soldier he was just taking pictures. The usual rules of communication are not in operation in front of these guns, behind these walls. Perhaps from his hospital bed, Mohammad felt it was a joke that he should try to photograph the soldiers at all, and that this could make a difference, sixty-five years after the dispossession of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians including Mohammad’s family, and forty-six years after military rule began in the West Bank and Gaza. It is not only that Israeli attacks threaten Palestinians’ rights to speak, as they have on many occasions. It is also that the conditions of Israeli occupation are such that it often seems it does not matter at all to Israelis what Palestinians say.

After the shooting, I contacted Reporters Without Borders / Reporters sans frontières (RSF) and the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) to inform them about the incident. While all journalists reporting on conflict in the occupied territories face risks, Palestinian journalists face increased risks of being injured and killed by the Israeli army. RSF called for the Israeli military to punish the soldier who they said had “deliberately shot a Palestinian photographer in the face.” The next day, the CPJ staff member told me his report would be out soon. He was waiting for an Israeli military response to his inquiry about the incident. I know from my reading of past CPJ reports that this is procedure, and I also know that the Israeli military rarely responds to inquiries about injured Palestinian journalists. Sure enough, CPJ published its report a day later, noting the lack of Israeli response. In decades of occupation, how many Palestinian lives have been destroyed, in part or in full, by Israeli army violence, and how often have soldiers been held accountable for their actions? Will RSF or CPJ’s report help to hold these soldiers accountable? Will Mohammad’s own photographs?

But whether or not the photographs Mohammad takes have an impact on Israeli society, Mohammad’s work does make a difference. In the past several months, the residents of Aida Refugee Camp and surrounding communities have revived popular protest against the wall erected around their community and against the intense militarization it has brought. Mohammad is documenting this bold uprising with creativity, skill, and bravery. His coverage is especially crucial because the uprising in Aida has not been supported by a widespread national movement. Histories and representations of Palestinian popular uprising are somewhat hard to come by. Mohammad’s photographs and video also express to a large and growing community of supporters around the world the urgency of what is happening.

The next time I spoke to Mohammad, he said he is doing ok, but in pain. He has an extended recovery ahead of him, starting with several operations. He wants to go home. Protests continue in the camp, he reminded me, and he wants to document them. I was silent for a moment. I want him to know that as much as his immediate community and his audiences abroad appreciate his coverage of protests, his other media work matters too. His documentary of the water crisis in Aida Refugee Camp, Everyday Nakba, has started to mobilize international action for safer water and environmental justice in Palestinian refugee camps. His video Just a Child documents both the injustice of military law and the agony of arrests as experienced within a Palestinian family. It will screen next week at the Chicago Palestine Film Festival. On a different note, his photography of Lajee Center’s dabka popular dance troupe brings his community joy and makes us proud. Some of this other photography, published in the book The Power of Culture, reflects on the politics of Palestinian representation itself. He also teaches photography and documentary production to youth, giving them the opportunity to express themselves.

As I think about Mohammad’s warmth and humor, I also want to remind him that his political contributions to his community go well beyond his media work. In moments of political crisis, he is one of the people who has sustained me and given me perspective on resistance and steadfastness, even though he is my junior. I know he has done the same for others. This is a long struggle, and being resolutely kind is in itself an important political act. So is our insistence on the idea that what we say matters, even if those with the most power (and the most guns) are not listening.

For Mohammad al-Azza, with warmest wishes for a smooth recovery.

[Mohammad al-Azza’s Facebook photography page, shows highlights of his work. He was also recently published on Jadaliyya.]

![[Israeli soldiers approaching Aida Refugee Camp. Image by Mohammad al-Azza]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/ApproachingAidaCamp_AlAzza_small.jpg)