Simon Jackson, “Diaspora Politics and Developmental Empire: The Syro-Lebanese at the League of Nations.” Arab Studies Journal Vol. XXI No. 1 (Spring 2013).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this article?

Simon Jackson (SJ): The article draws on my current book project, provisionally titled Mandatory Development: The Global Politics of Economic Development in the Colonial Middle East. The book is about the socioeconomic development regime in French Mandate Syria-Lebanon between the world wars, considered at a variety of scales, from the local to the imperial, international, and global. This particular article concentrates on the role of the Syro-Lebanese diaspora in the political economy of the Mandate, from the end of World War I into the 1930s. I show how members of the diaspora, notably in the Americas, organized, petitioned, campaigned, and volunteered to change the emerging political economy of Lebanon and Syria. I explain how diverse the diaspora was politically, but also how important to shaping events in and perceptions of the French Mandate. Whether from Rio de Janeiro, Detroit, or elsewhere, distance was no barrier to diaspora participation in Syrian and Lebanese socioeconomic development, a conclusion with implications for methodological nationalists, but also for scholars for whom colonial empire has become the privileged unit of analysis.

Like many younger researchers, I got interested in this topic in the middle of what Sally Howell, in her work on Arab Detroit after 9/11, calls the “terror decade.” This period of course saw the United States and its allies occupy and radically transform Iraq and Afghanistan. But it also saw the fullest unfurling of post-Cold War US hegemony, with its accompanying global political economy and sprawling ideological agenda. The co-constitutive entanglement of politics at local and global levels was a striking aspect of the period, as was the aggressive promulgation of economic narratives as a rhetorical and practical justification for political action in the wake of a global conflict like the Cold War.

The politics of those years accompanied my archival research, and stoked my interest in how narratives of the economic past and dreams of future development interleave with international politics and the political economy of colonial occupation. Add in the inspiration provided by scholars of inter-war Syria and Lebanon such as Elizabeth F. Thompson, and you get a sense of some of the spurs for this project.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the article address?

SJ: The big argument of the article and of my wider project is the need to understand the French Mandate period in Lebanon and Syria in terms of its political economy: the practices, institutions, and debates in which the social relations of production bleed into political struggle. While there is some terrific new research on Lebanese sectarianism, for example, or on counter-insurgency and the production of space during the Syrian Revolt, few scholars have yet to respond to Fawwaz Traboulsi’s call for more research on political economy.

Hence, while the protagonists in my account include clerics—such as the Maronite Patriarch—they are discussed in their capacity as lobbyists for hydroelectricity or shareholders in “national” cement companies, rather than as theologians or politicians. Likewise, while Syrian insurgents and the French colonial military both figure importantly, the former are shown fundraising in the United States, and the latter is shown organizing and participating in trade fairs in Beirut, and building roads. The advantage of such an approach, recently deployed in the case of British Palestine by Jacob Norris, is that it complements conventional political or social histories by showing that postwar socioeconomic development—as a practice and as a debate—crossed party and class lines as well as national and imperial frontiers. Development provided a conceptual repertoire to groups—such as colonial officials, nationalist insurgents, Beirut (and Trieste or Marseille) businessmen, and Detroit Arab-American factory workers—that historians often cast purely in opposition to one another, or else fail to consider simultaneously. Moreover, a focus on the ideology and practices of economic development reveals important continuities between the 1920s and 1930s and the post-World War II era more usually understood as the “development age.”

French colonial history, meanwhile, remains powerfully focused on the major sites of settler colonialism in North Africa, on the dynamics and legacies of slavery in the French Atlantic system, or on the paradoxes and antinomies of Republican Empire from the 1870s to the post-independence era. Rarely considered within this field, due to its small size and the brevity of formal French control, the League of Nations Mandate in Syria and Lebanon nevertheless opens up new perspectives for French colonial historians. It does so partly because of its explicit embedding in the Wilsonian legal-political international order after World War I: the “colonial situation” acquired a new level of complexity and a new exposure to international public opinion through the League of Nations in Geneva. But the Mandate in Syria-Lebanon also challenged the “civilizing” and racializing categories through which the French colonial empire produced social hierarchy, individual subjectivity, and political spaces. I show how Syrians and Lebanese worked successfully to co-opt systems of racial and colonial classification in ways that cannot be grasped by condemnations of imperial republicanism. For instance, my archival work uncovered Lebanese petitioners to the League of Nations in the 1920s who pointedly compared Lebanon to Czechoslovakia or Hungary: a post-imperial country in need of technical assistance from and membership in the “international community.” Such sources, connecting Beirut and Damascus with Budapest and Prague, help me to blur still-strict disciplinary and methodological barriers between “Europe” and the “Middle East.”

Finally, the article and the wider project contribute to the burgeoning literatures on the Arab Americas and the League of Nations. Two decades on from Albert Hourani and Nadim Shehadi’s landmark collection on the Lebanese diaspora, written in the context of the Lebanese civil war, historians like Camila Pastor and Stacy Farenthold are doing wonderful new work on diaspora politics and society, examining the complexities of the diaspora world and the simultaneous political commitments maintained by diaspora members in a transnational social field. As the military auxiliaries, arms shippers, and alarmed humanitarians described in the article attest, it ought henceforth to be difficult to write the modern history of Syria and Lebanon without granting a major role—proportionate to the part they played—to Syrians and Lebanese who were also Brazilian, French, or Mexican.

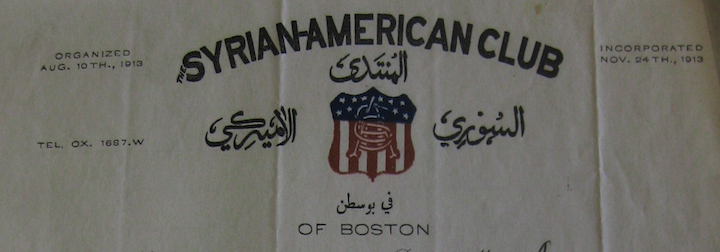

[Detail from a Jun 1917 letter from Faris Malouf, president of the Boston Syrian-American Club, to the local representative of the

wartime US Liberty Loan drive. Photo by Simon Jackson, published by permission of the Arab American National Museum.]

Likewise, the League of Nations, recently resurrected as a topic of inquiry by international historians like Susan Pedersen, Patricia Clavin, and Clifford Rosenberg, is increasingly seen in a continuum with the United Nations era after 1944. Continuities of technical, economic, and legal norms and categories between the two eras are far more significant than historians previously realized, a fact with consequences for global narratives of the history of economic development, as well as for environmental and economic histories of the Eastern Mediterranean. Moreover, as the article shows, the League provided the Syrian and Lebanese diaspora with an amplifier for its varied demands, and with a political threshing floor, on which varied groups fought to rise to representative status.

J: Who do you hope will read this article, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

SJ: The article will be of interest to scholars working on the modern history of Lebanon and Syria, and especially on the Mandate period. It should also be of interest to historians of French colonial empire, especially those working on political economy, and to international historians interested in the intersection of empire, economic development, and international organizations. The article is also explicitly in conversation with historians of diaspora, notably the Syro-Lebanese diaspora.

I would also like the article to find a wider readership among those interested in the current crisis in Syria, which massively exceeds that country’s territorial frontiers. Emigration and refugees, diaspora politics and funding of revolt, predictions of renewed prosperity or catastrophe, and the influence of great powers, refracted through international institutions, are all critical to the region right now. My treatment of the same issues in an earlier era can help us to understand the present. Moreover, political economy does not get nearly enough time in the current discourse on Syria, which is dominated by sectarian questions: I hope the article makes a good case for a political economy lens.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

SJ: I’m working on several new questions. One article project is on the history of Fords and Fordism between Beirut and Detroit, while another is an environmental history of Moroccan phosphates from the French Protectorate to the Green Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s. I’m also part of an ongoing interdisciplinary collective research project on law and property in Lebanon, in which my contribution revolves around cadastral surveying and mortgage debt in the 1920s. Finally, I am co-editing a collection of articles on the theme “Transformative Occupation in the Twentieth Century Middle East.”

J: What methodologies did you use in your research for this article?

SJ: The research took me to archives in Lebanon, France, Switzerland, the UK, and the US. Theoretically, I draw on the insights of historical sociology and cultural political economy to treat economic life not in terms of quantitative positivism, but by paying attention to the entanglement of economic ideology and practice with historical and cultural narratives and categories. In terms of scale, I wanted to write a history that would avoid cantonizing the question of economic development within a national or imperial unit by moving from local neighborhoods and associational life to international and even global webs of connection.

Excerpt from “Diaspora Politics and Developmental Empire: The Syro-Lebanese at the League of Nations”

Syro-Lebanese clubs and organizations in the diaspora communicated with one another in part through newspapers, where they published their critiques of the mandate.[1] Through correspondence and by reprinting each other’s articles, these institutions fostered social spaces in which discrete communities across the world debated ideas and evolved politically. Clubs organized existing commercial, cultural, and familial connections, and newspapers encouraged collective adherence to political agendas. For example, Assalam, a newspaper based in Buenos Aires, printed increasingly anti-mandate articles during the early 1920s.[2] The paper took a pro-Hashemite line in 1919 and strongly criticized the French arrest of the Conseil du Liban, an Ottoman-era representative organization that had tried to rally to Faysal in Damascus. Assalam regarded such actions as colonialist and compared them to French aggression in the protectorate of Tunisia, its colonial departments in Algeria, and in the colony of Madagascar. In correspondence with reproving French consular officials in Buenos Aires, the editor of Assalam, Alejandro Shamun, pointed out that he was not dogmatically anti-French, but that he retained the right to criticize French policies and to practice the ideals of liberty that French power only superficially supported.[3] La Patrie, a French-language, pro-Faysal, Syro-Lebanese newspaper in Santiago, Chile, went on to reprint Assalam’s articles.

Indeed, as the reproaches of the French consul in Buenos Aires suggest, influenced by their interlocutors in the Lebanese diaspora the French continued to envisage the Syro-Lebanese diaspora as potential investors in the French-managed “regeneration” of Syria after 1918. What made this notion of regenerative investment viable, without risking any loss of French power, was precisely the idea of the diaspora as wealthy and politically distant. Colonial authorities imagined that the diaspora could therefore act not only as commercial agents to French businesses and ideas, but also as silent—and silenced—partners in the Mandate’s political economy. For instance, the French Information Bureau wrote in 1927 that:

Many Syro-Lebanese make their fortune [once they emigrated] and possess resources that could almost independently finance the economic development of their country of origin, by sending the requisite capital there. If a tenth of them, say 100,000 people, could invest a few thousand francs in each of the industrial and agricultural businesses that will regenerate Syria, imagine what prosperity they could guarantee the country.[4]

The diaspora responded to this wishful thinking in multiple ways after World War I. Certainly, it had collectively remitted capital to Syria-Lebanon, thereby supporting the economy there. During the war, the diaspora engaged in numerous relief efforts, such as the Union of Syrian Ladies sending aid parcels from Alexandria or Maronite intellectual Charles Corm organizing food distribution efforts in Beirut in 1919. It is not surprising, then, that some groups bought into the French vision for a Mandate in Syria and Lebanon. In October 1918, the French consul in New York City met with two predominantly Maronite, pro-French, Syro-Lebanese organizations and the editors of five community newspapers to record those groups’ enthusiastic support for a French Mandate. We should note again the privileged access Christian Lebanese enjoyed to French power. As Fawwaz Traboulsi states, in Syria-Lebanon itself, immediately after the war the American Crane-King mission—sent by the Paris Peace Conference to assess the political preferences of the Syrian population but whose conclusions the great powers then ignored—received 1,863 petitions and delegations from thirty-six cities and 1,520 villages. But while “fully 80 percent of the respondents voted for a united Syria, 74 percent supported independence and 60 percent chose a ‘democratic and decentralized constitutional monarchy’ […] in the event of the imposition of a foreign mandate on Syria, sixty percent opted for an American mandate, a much smaller number for a British mandate, and only 14 percent, mainly Lebanese Maronites, requested a French Mandate.”[5] The support offered to the French Consul in New York represented only one (minority) perspective on the French Mandate and its economic development plans for Syria and Lebanon.

Unsurprisingly then, as early as 1920, after the French deposed the Hashemite monarchy in Damascus, a group called the New York City Party for the Liberation of Syria published a pamphlet arguing that the French had come to Syria unwanted and uninvited. It added that even in 1919, only a few Lebanese had been pleased with the new mandate and that they had since “repented.” Cataloguing what it described as the “crimes of the regime,” the pamphlet focused on the political economy of Syria and Lebanon. It noted that national companies, such as the railways, had already been allocated to French interests, thus “depriving the indigènes.” The pamphlet argued: “the concessions of the country are an easy target for the colonizers, and they farm out such businesses like a feudal privilege to those indigènes with whom they’re most pleased.”[6] The rhetorical violence of this position drew on the language of French colonialism and the highly charged term of indigène, a legal category describing a condition of legal-political subservience, to signal a distance between the diaspora in New York City and Syro-Lebanese in the Levant. And even as it did so, it spoke on the behalf of the latter, using the US diaspora’s greater freedom from censorship to influence French policy in the Mandate. Second, and more directly, the pamphlet declared diaspora contempt for the wealthy Syro-Lebanese whose collaboration with the “regime” had earned them access to concessionary opportunities. This shows how diaspora communities’ freedom from censorship afforded them opportunities to offer condemnations or solutions that those in the Mandate territories could not.

Another example of this type of “long-distance criticism” appears during the years of the Great Revolt in Syria (1925–1927), when the French Foreign Ministry received numerous letters from Christian Syro-Lebanese diaspora communities seeking to leverage their strong connections to the French authorities. Scholars like Michael Provence have shown how complex the Revolt’s dynamics were, operating as much along class and rural-urban divides as through sectarian divisions.[7] However, Syro-Lebanese Christian diaspora petitioners in the United States certainly engaged in sectarian advocacy. More extreme voices among these emigrants requested the extermination of “Druze rebels,” the Druze community in the Levant, or even “Muslims” in all of Syria. One example is a letter to the New York Times in November 1925. In it, Naoum A Mokarzel, editor of Al-Hoda newspaper and the president of the Lebanese League of Progress, stated that French protection of Lebanese Christians through the Mandate was the only barrier between them and an unholy alliance of American missionaries, foreign powers, and “the ruthless fanaticism of the Mohammedan element.” As the New York Times summarized Mokarzel’s intervention: “A Western Power’s Protection is Declared Essential until Islam learns to be Tolerant—Situation unchanged since the Crusades.”[8] Mokarzel’s position attracted further letters to the editor from other Lebanese Christians in the diaspora who took exception to his opinions. Indeed, it is difficult to say how representative Mokarzel’s views were. Further research should seek to quantify diaspora responses in the press to establish the prevalence of the different reactions to the Revolt and the weight and social position of the respective readerships. However, Mokarzel’s anti-Muslim and pro-French line emerged from an influential tradition of Franco-Lebanese Christian thought.[9]

NOTES

[1] Clavin, “Defining Transnationalism,” 428.

[2] The Argentinean Syro-Lebanese community numbered 110,000 and was highly involved in textile trading.

[3] CADN, Fonds Buenos Aires, Légation puis Ambassade, Série 1887-1925, Carton 99, doss. 1530, Syrian commerce in Argentina and attitudes to events in Levant by Syro-Lebanese press in Buenos Aires, Assalam October–December 1920.

[4] CADN, Fonds Beyrouth, Premier Versement-Cabinet Politique, Dossiers de Principe 1920-1941, Carton 419, Colonies Syro-Libanais à l’étranger, Notes on the representation of Syrians and Lebanese abroad. Prepared by the Services des renseignements du Levant, 15 November, 1927.

[5] Fawwaz Traboulsi, A History of Modern Lebanon (London: Pluto, 2007), 78.

[6] CADN, Fonds Beyrouth, Premier Versement-Cabinet Politique, Dossiers de Principe 1920-1941, Carton 419, Colonies Syro-Libanais à l’étranger, Pamphlet dated August 1920, transmitted by French Consul at New York to MAE.

[7] Provence, The Great Syrian Revolt.

[8] Naoum A. Mokarzel, “Syria a Religious Problem; A Western Power’s Protection Is Declared Essential Until Islam Learns to Be Tolerant—Situation Unchanged Since the Crusades,” New York Times (29 November 1925).

[9] Asher Kaufman, “Henri Lammens and Syrian Nationalism,” The Origins of Syrian Nationhood ed. Adel Beshara (Routledge, 2011).

[Excerpted from “Diaspora Politics and Developmental Empire: The Syro-Lebanese at the League of Nations,” by Simon Jackson, by permission of the author. © 2013 The Arab Studies Journal. For more information, or to purchase this issue or subscribe to the journal, click here.]