Louise Cainkar, “Global Arab World Migrations and Diasporas.” Arab Studies Journal Vol. XXI No. 1 (Spring 2013).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this article?

Louise Cainkar (LC): This article was developed from a keynote speech I delivered at the Conference on Arab World Migrations and Diasporas, organized by Georgetown University’s Center for Contemporary Arab Studies. When contemplating the keynote, I considered deeply what my particular contribution would be to a room full of multi-disciplinary scholars of Arab migrations and diasporas. I decided to focus on constructing a global context within which all of us—historians, sociologists, anthropologists, scholars of comparative literature, cultural studies, diasporas, and others—could situate our work. Such a context would allow us to converse across disciplines and theoretical frameworks, as well as begin speaking in comparative ways, which I consider useful and important. We know that there are variations and commonalities in the experiences of Arab world migrants and among Arab world diasporas; we should begin to talk about what matters and why it matters.

I also think that irrespective of disciplines, our shared concern for human dignity—which faces incredible challenges and motivates considerable action in migratory and diasporic experiences—establishes the foundation for these cross-disciplinary conversations.

J: What does the article address?

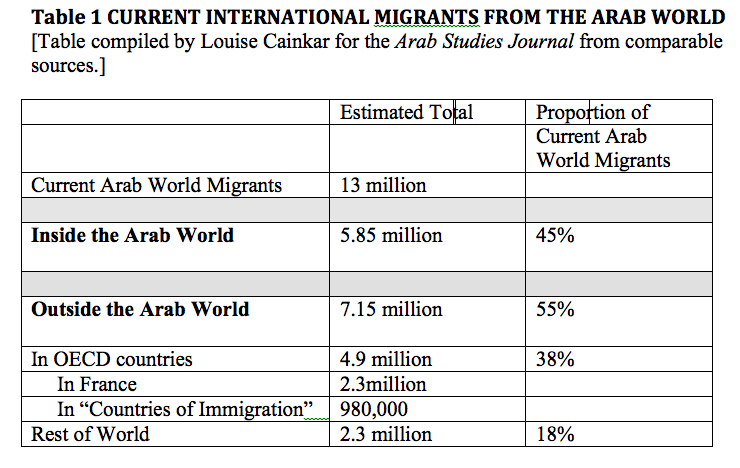

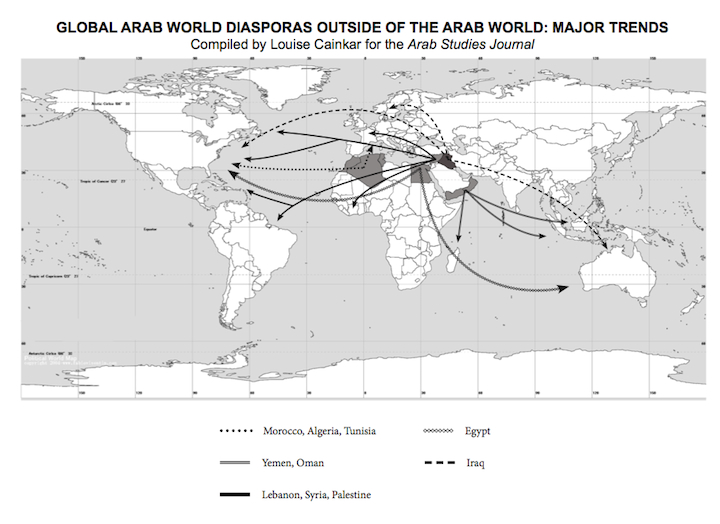

LC: The article takes on the challenge of constructing an overarching global context of Arab world migrations and diasporas from both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. While one can find a plethora of numbers on Arab world migrants, the real challenge lies in finding numbers that count the same things, allowing for comparisons. After speaking to the caveats that exist around the social processes of counting and numbers, I provide comparable data on current major Arab world migrations that offer readers a sense of the proportion and range of current migratory movement. I then examine some of the major quantifiable differences across these migrations. For example, I attempt to answer the question, “How are Arab world migrants to major destinations in Europe demographically similar to and different from Arab world migrants in the US, Canada, and Australia?” Once we have established these differences and then examined the varying socio-political contexts within which they live (for example, naturalization policies), we begin to grasp the complexities that interact to produce meaningful differences in their experiences. I also present a quantitative overview of the broad reach of global Arab World diasporas, which include not just current migrants but generations going back, in some cases, for centuries. While accuracy in those numbers was quite elusive, I laid out the groundwork for other scholars to revise, recognizing that one must investigate matters of definition and measurement in each place.

I also sought to provide a qualitative overview of our collective body of work, which proved to be a more daunting task than the quantitative challenge! One thing I discovered was that the English language scholarly literature varied significantly in content and focus, depending on whether the persons being studied were living inside or outside of the Arab World, even though quantitatively the differences are not massive. We do not ask the same questions of, or have the same curiosities about, these two groups of people. I decided to focus my qualitative commentary on this phenomenon, and on how we might equally humanize these two groups.

J: How does this article depart from and/or connect to your earlier research?

LC: Most of my work is highly qualitative, although there is almost always a quantitative dimension to it. This piece is evenly balanced, I think, between quantitative and qualitative. Also, most of my recent work has been focused on migrants and their children in the United States, so taking the global perspective was a nice shift.

J: Who do you hope will read this article, and what impact do you want it to have?

LC: I hope scholars and students of Arab World migrations and diasporas from all disciplinary perspectives will read this article so we can enhance cross-disciplinary conversations and comparative analyses. I think most scholars of Arab World migrations and diasporas are keenly aware that multiplicities of realities, identities, and places have individual and group meaning for migrants and diasporic communities. I think all of us need to move a bit out of our boxes and categories and think relationally.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

LC: I am analyzing data I collected in Palestine, Jordan, and Yemen on the transnational experiences of Arab American, mostly Muslim, teenagers whose parents took them “back home” for high school. I conducted ninety-three interviews with such youth on a range of topics, including migration histories, identities, understandings of race, religious upbringing, and diasporic imaginations. Although I have always been interested in this phenomenon, I think understanding its dimensions and impacts takes on added meaning in the context of repeated allegations that “going back” creates conflicts of loyalty for American Muslim youth. We have little research with which to challenge these charges. While I am at the beginning stage of analysis, my overall impression is that these youth see themselves as emerging from these experiences with more dignity, as more globally grounded, and with a greater appreciation of their multi-faceted selves, despite pressures they face to choose one identity.

Excerpts from “Global Arab World Migrations and Diasporas”

In the process of searching for comparable quantitative data, I discovered that categories of quantification have a reifying tendency that has infected our qualitative research as well. These categories direct our gaze in specific ways that cause us to highlight certain matters while overlooking others, creating an overall imbalanced body of scholarly literature on Arab world migrations and diasporas. This imbalance is particularly notable when one compares the English-language scholarly literature on Arab world migrants living within the Arab world to that on Arab world migrants living outside of it. In the case of the former, the dominant focus is on state policies, occupations, labor conditions, and remittances while the latter tends to emphasize social, cultural, and political struggles, adaptations, constructed memories, and hybridities. This pattern of scholarship might make sense if we believe that official categories of migrants should drive our intellectual curiosities, but my argument is that when we do so, we miss a lot.

[…]

One way of thinking about human dignity and its relationship to migrations and diasporas within and outside of the Arab world is to cast off analytic, conceptual, and technical categories of migrations and diasporas and think instead of migration and the popular revolutions that have occurred across the Arab world (often referred to as “the Arab Spring”) as two sides of the same coin. Migration and revolution are acts of human agency that demand more. Both emerge from discontent with authoritarianism, corruption, blocked aspirations, obstructed possibilities, and social inequalities, and the loss of a sense of agency that accompanies these conditions. Neither migration nor revolution is principally a response to poverty, even though high levels of it may be present. Indeed, research shows that it is not the poorest members of any society that are likely to lead revolutions or to migrate, in part because of the greater damage done to their agency. Only at poignant, some call them epic, historic moments do sweeping waves of popular rebellions such as “the Arab Spring” occur. Migration, on the other hand, is a type of unremitting human rebellion. It is the perennial and persistent, indeed unstoppable, human quest for dignity and autonomy. While the place in which the migrant lands, the way in which s/he arrives, and the paperwork s/he carries may determine his or her category as a migrant, the quest of all migrants is the same.

[...]

Of the estimated thirteen million current Arab world international migrants, fifty-five percent (7.15 million) live outside of the Arab world. They are significantly concentrated in the western European and North American countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The remaining forty-five percent (5.85 million) live in the Arab world. Nearly seventy percent of migrants from the Arab Maghrib live in Europe, although some one million of them live in other Arab countries. On the other hand, nearly seventy percent of migrants from the Arab Mashriq (which the IOM defines as Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Syria, and Yemen) live in the Arab world, mostly in GCC countries.

[…]

Striking differences in socio-political context and socioeconomic characteristics emerge when the dominant trends for Arab world migrants living in Europe are compared to those living in the OECD “countries of immigration”—the United States, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. These differences include migration history, state ideology, immigration policies, place of origin, human capital, employment, proportionate share of the population, and naturalization rates. These dissimilarities must certainly matter to the qualitative experiences of these migrants, but we have not done sufficient comparative work to specify precisely how they matter. At the same time, there are some overarching similarities across these countries that have increased in momentum over the past decade. I provide broad outlines of these differences and similarities below in an effort to encourage more comparative thinking among scholars of Arab world migrations and diasporas.

[…]

In some places that Arab world migrants go, however, return is both the norm and the mandate. In these places, social and political membership are not even remote possibilities for migrants, who are informed a priori that there is no room to aspire for more than that what their visa or paperless status will allow. Here, human beings on the same quest for dignity, agency, and autonomy as all others are called labor migrants, contractual employees, or illegals. The state and host citizenry treat them as persons whose needs are limited to a paycheck and whose capabilities can be justifiably circumscribed, when the main way in which they are actually different from other migrants is in their lesser set of civil, social, political, cultural, and economic rights. Here we turn to Arab world migrations and diasporas within the Arab world. I suggest that instead of speaking of “labor migrants” or “contract workers,” as is the common pattern, we should more accurately speak of labor migrant and contract worker states, for it is the state that defines the difference and not the migrant.

[...]

As scholars, we could advance the study of Arab world diasporas by refining our understandings of how ideologies, policies, cultures, and interpretations intersect to produce different outcomes in different places. Why does the Arab world diaspora in much of Latin American and the Caribbean look qualitatively different in terms of social and political integration than it does in the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Europe, and West Africa? For example, when compared to their social positions in other diasporic locations outside of the Arab world, the Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian communities in the Caribbean and Central and South America appear to be the most socially and politically integrated, to have the highest rates of intermarriage with the local population, and to have achieved the highest levels of political office, although a comparison with, for example, Yemenis in Southeast Asia may reveal similar patterns. Do we really understand the ways in which Arab world diasporas in Malaysia and Indonesia are similar to and different from those in other locations? Scholars seeking answers to questions not only of “what” but “why,” who want to understand process and causality with regard to racialization, language and culture retention, identities, and social and political integration, need information on the ways in which local and global context shape social behavior. Developing this understanding requires attending to policies and patterns historically and comparing them across time and place. Considerable research lies ahead for scholars in the exploration and comparison of the contours of similarity and difference situated in place, and their implications for social life across the wide-ranging global Arab world diaspora.

[Excerpted from “Global Arab World Migrations and Diasporas,” by Louise Cainkar, by permission of the author. © 2013 The Arab Studies Journal. For more information, or to purchase this issue or subscribe to the journal, click here.]