Deep in thought while in transit at Amman’s international airport in 1979, I missed my flight to Beirut. Fortunately a competing airline had a plane thirty minutes later. My waiting friends met me in frenzy; it was revolutionary Beirut and although they had cause to worry their anxiety soon turned to glee when they informed me that our car was entering the liberated zone. Fresh from the laziness and loneliness of the Midwestern United States, in Lebanon’s capital I found a people flying high with activity, and a venturesome, optimistic, and selfless sense of commitment. Every activist was glittering and the variety of their personalities made the individualists of America seem like rubber stamps of each other. It was in this amazing ambiance that I first met Mustafa al-Hallaj as he shone brightly during his highest moments. In those days of Beirut, when evening came people were on the move, visiting or attending events, exchanging ideas, arguing, smoking, eating, and welcoming. With distinguished sculptor and arts activist Mona Saudi, who was then head of the Plastic Arts Section of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), I made the circuits and visited fellow artists. We ran into Mustafa one afternoon on Hamra Street, and he invited us to drop in later that evening to his tiny, humble abode. After several artists had arrived, Mustafa went out to bring food, alcohol, and cigarettes; as he was the exquisite master of ceremonies, the salon began when he returned.

My impressions from our brief visit are confirmed by artist Samir Salameh, who lived and worked in Beirut from 1972 through 1979. He describes Mustafa’s Hamra Street studio as an open salon where artists congregated, and where food, drink, and conversation were enjoyed. Salameh remembers that “All the artists felt tied to the cause . . . We talked about sincerity in art and a commitment to our subject matter . . . If an artist was concerned with politics and did poor work we would help him improve . . . Many of us liked Picasso and felt he was the master of modern art. We always talked about Diego Rivera and the Mexicans . . . We loved the Futurists and the Cubists.”[1] Throughout the revolutionary artistic and intellectual flowering in Beirut of the 1970s, Palestinian liberation artists engaged in a spirited dialogue on aesthetics; and Mustafa was at its inspired center.

My second exchange with Mustafa was in 1981 in Oslo. Most of the artists who were active in the Liberation movement had gathered there for an exhibition at the Kunstnernes Hus, which was sponsored in cooperation with the PLO. We were all glad to see each other and felt like a group of long lost friends who joyfully found themselves in the welcoming arms of the Norwegian artists. While we were not used to acceptance by a mainstream museum of contemporary art, our Norwegian counterparts explained that as artists they had a powerful say in the programming of the Kunstnernes Hus; their proximity to the then Soviet Union made such sensitivity to artists possible. What the Norwegian artists found through the exhibition was that in conditions of revolution the arts are both stimulated and liberated regardless of the difficulties of struggle.

The meetings and exhibitions in Oslo were a habitat that was seemingly natural to Mustafa. He was the enthusiastic intellectual who courted conversation and discussion. He made sure to visit all the Norwegian artists‘ studios and his enthusiasm carried us everywhere. It was then that I first came to know him as an optimistic catalyst. I did not see him again until the mid 1990s but kept in touch with his news. Living in Damascus at that point he was extremely depressed but slowly recovering. I visited him often in Syria after his period of depression during the late 1990s and the early 2000s. Many of those meetings were formal as I conducted lengthy interviews with him in which he discussed his artistic practice.

Our last meeting was in December 2002, when I brought the director and curators of the Station Museum in Houston, Texas to his studio as they sought artists for the “Made in Palestine” exhibition. His conversational depth, language difficulties notwithstanding, combined with his genuine hospitality, enchanted the curators. Mustafa and James Harithas, the Station Museum’s founder and director, became immediate friends. Mustafa could shine like the master that he truly was on so many levels.

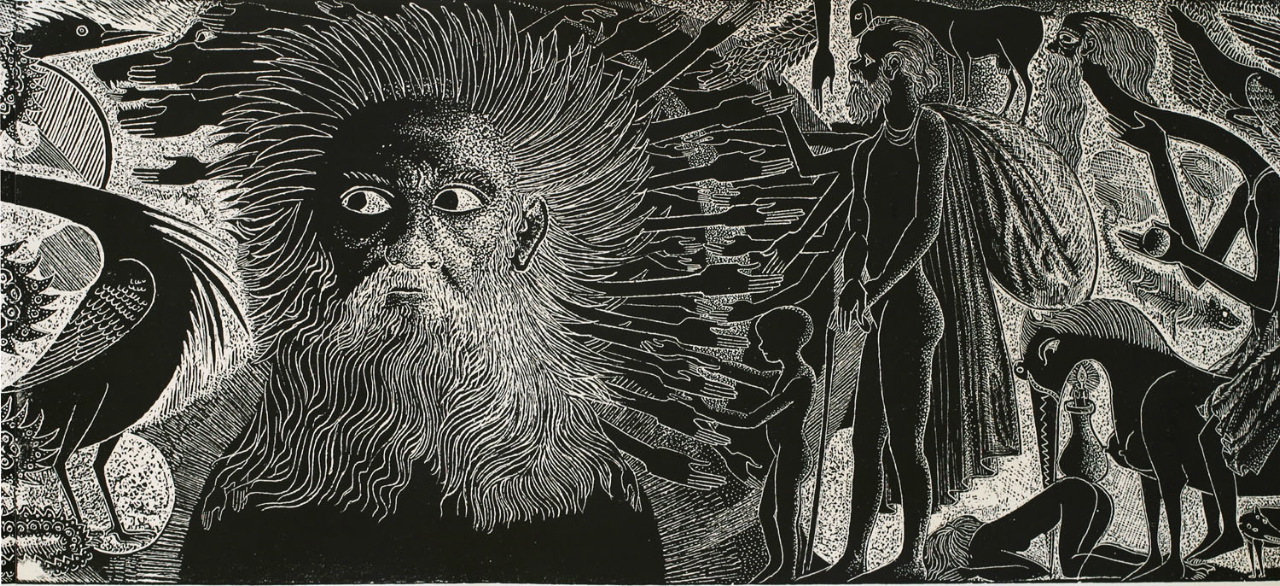

[Installation view of a selection of Mustafa al-Hallaj`s masonite print "Self Portrait as Man, God, and the Devil" (1996-2002) as part of the Made in Palestine exhibition at the Station Museum of Contemporary Art, Houston, Texas. Image courtesy of the author.]

[Installation view of a selection of Mustafa al-Hallaj`s masonite print "Self Portrait as Man, God, and the Devil" (1996-2002) as part of the Made in Palestine exhibition at the Station Museum of Contemporary Art, Houston, Texas. Image courtesy of the author.]

He was very excited at the prospect of coming to the United States to be in the show. The second US war against Iraq was about to begin and most artists were angry and not particularly excited to be connected to “America.” My presence with the curators persuaded most; but some even insisted that they loan their artwork to me and not the museum. Mustafa, on the other hand, could see through international propaganda; he understood the political and class levels within all states. Sadly, on 16 December 2003, the day we left Syria, Mustafa received a phone call misinforming him about who would represent his artwork for the US exhibition. His wife, Ibtisam Husein Zubaidy, later told me that after receiving the call he became very angry. As he paced back and forth across the floor of his studio, he accidentally kicked a space heater that spilled fuel throughout the room and quickly caught fire. Ibtisam urged him to run out but he insisted on saving his early work. When the firemen arrived at the front door, they could not reach him until they finally paid attention to his wife’s urging and went to the back door where they found him unconscious. He was taken to a hospital where he died the following day.

His life

Mustafa al-Hallaj was born in Salama, a small village in the district of Jaffa, in 1938. His father worked in the fruit groves surrounding the famous port city. This humble origin gave him a powerful materialist outlook and deep memories of the landscape of Palestine. His childhood, however, came to an end at a young age. “I was ten at the time of the Nakba in 1948" he once said, "and we escaped first to al-Lydd, then to Ramallah, then Damascus, then Beirut, then Egypt, all in one year.”[2] Mustafa studied sculpture at the College of Fine Arts in Cairo. Following this initial artistic training, he received an appointment to the Luxor Studios, a special distinction, where he focused on the history of ancient Egyptian, Canaanite, and Phoenician art.

After twenty-five years in Egypt, Mustafa traveled to Beirut at age thirty-five to take part in the revolution. “I was in Luxor thinking – sitting, in fact, in the lap of Amenhotep III -- when I heard the song of the West Bank on a radio and I felt suddenly that my umbilical was tied to the Sidr tree in Salama,” he recalled in an interview. This tree occupied the central square of his village and appears in his pictures. This was the moment that he decided to join the movement and so he left Egypt for Damascus, and in 1974 moved to Beirut to the epicenter of artistic and revolutionary activity. Mustafa spent eight years in Beirut, yet the city became untenable for Palestinian artists with the defeat and dispersal of the movement in Lebanon in 1982. Thus he returned to the more welcoming metropolis of Damascus, mother of the Levant, where he established himself at the Naji al-Ali gallery. Mustafa lost the major content of his studio when leaving Beirut under severe bombing. Although his original woodcuts and masonite engravings were fortunately saved, 25,000 prints were lost. After an acute period of devastation, he finally returned to his former social role and became the patriarch of Palestinian artists in Damascus, who recognized his historic importance. There, Palestinian artists often exhibited together and received official Syrian recognition for their work. He remained in Damascus until his death.

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, "Self Portrait" from the masonite print "Self Portrait as Man, God, and the Devil" (1996-2002). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, "Self Portrait" from the masonite print "Self Portrait as Man, God, and the Devil" (1996-2002). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

Mustafa as arts activist

As an artist, writer and journalist, Mustafa was active and outgoing. His fellowship with poets, writers, and journalists was equal to that with artists. He exhibited internationally and received recognition. He organized art shows, talks, and festivals. If he was not organizing an event or an exhibition, he was attending or contributing to one. On the third anniversary of Mustafa’s passing, his fellow journalist Qasi Saleh also noted that he organized festivals of theatre and film.[3] The widely known Palestinian painter Ismail Shammout, father of the Liberation movement, wrote an obituary on the occasion of Mustafa’s death in which he gives a glimpse of the dimensions of Mustafa’s participation in political and intellectual events:

I met him for the first time in 1968 in Sofia. He was a member of the Palestinian delegation to the International Festival of Students and Youth, which met in Sofia that year. He brought with him two wooden panels on which he had carved and burned the stories of Palestinian tragedy and exhibited them in one of the squares of Sofia.[4]

Another glimpse into his activism and the positively charged atmosphere of the revolutionary movement is given to us by his own description of the “Karameh” exhibition in Amman in 1969, as he related that the exhibition was clearly intended as a celebration of the expanding revolution. It served not only as an artistic event but also as a propaganda and information show. It contained children’s drawings, photographs, paintings, sculptures, maps, prints, books, stamps, clothes, recordings of songs of the revolution, and other related material. Artists from across the Arab world and from outside the region joined in. The exhibition opened in the Hall of the Union of Engineers in the Amman neighborhood of Shmeisani and after its initial proceedings its dynamic energy was carried on according to Mustafa who recalled, “We strung twelve tents together in Wihdat refugee camp [near Amman] for the people to see and the show later traveled to Damascus, Kuwait, and Morocco.”[5] While initially living in Damascus for a brief period after leaving Egypt, and later residing in Beirut, he could travel easily between the two cities and Jordan’s capital, crossing the national borders between them. In collaboration with artist Abdul Rahman al-Mozayen and others, Mustafa personally transported work to and from exhibitions, essentially building the artistic movement.

Mustafa only briefly practiced as a sculptor, abandoning it to explore the art of pictures in its variety of media. Focusing on printmaking, he experimented with different techniques and eventually concentrated on the formal range of the woodcut. He first began to use masonite and plastic sheeting as plates, often using a variety of uncouth tools such as nails to scratch into them.[6] In the end, he settled on using a jeweler’s drill to engrave masonite plates, which is the technique that I witnessed him use on his final major work during my repeated visits to his studio in Damascus.

During the 1980s, in addition to his prints, he began using tinted plasters to create paintings on board. The plasters were based on the medieval craft of ceiling decoration using colored gesso, a craft that is still alive in Damascus. These old formulas generally used animal glues to hold the various powders together and are unlike modern plastic gesso. On one particular research trip, I went about the Old City of Damascus inquiring about this method and began to learn of its required materials through the knowledge of local craftsmen who delighted in conversation in their small shops.

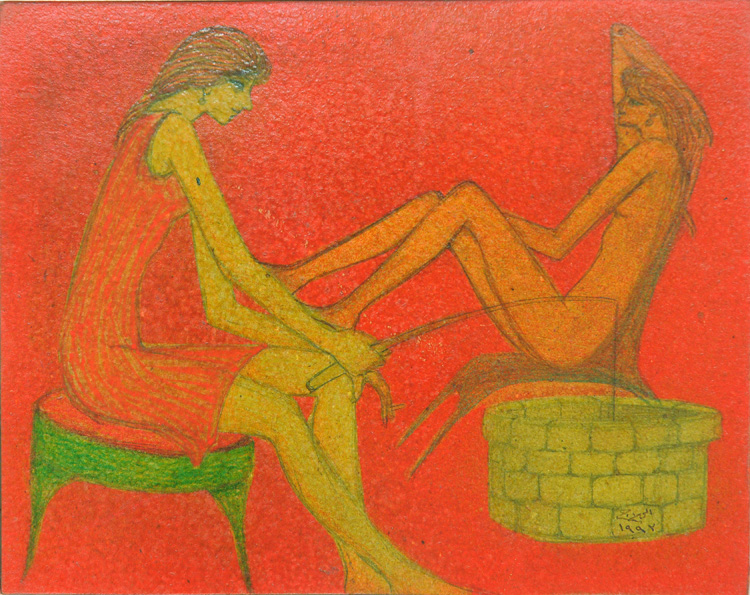

Like most of Mustafa’s work, the flavor of his brightly colored paintings is reminiscent of the fables of ancient wisdom, such as the stories of Kalila wa Dimna of early medieval Indian, Persian, and Arab tradition. His form in color is no less masterful than in the stark contrast of black and white prints. A good example is a small, untitled painting of two women against a bright red background, one sits on a stool fishing in a well while another is nude lazing in an easy chair. He explained that such imagery is about types, those who focus on work and those who focus on pleasure.

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, untitled (1992). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, untitled (1992). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

Subject and symbolism

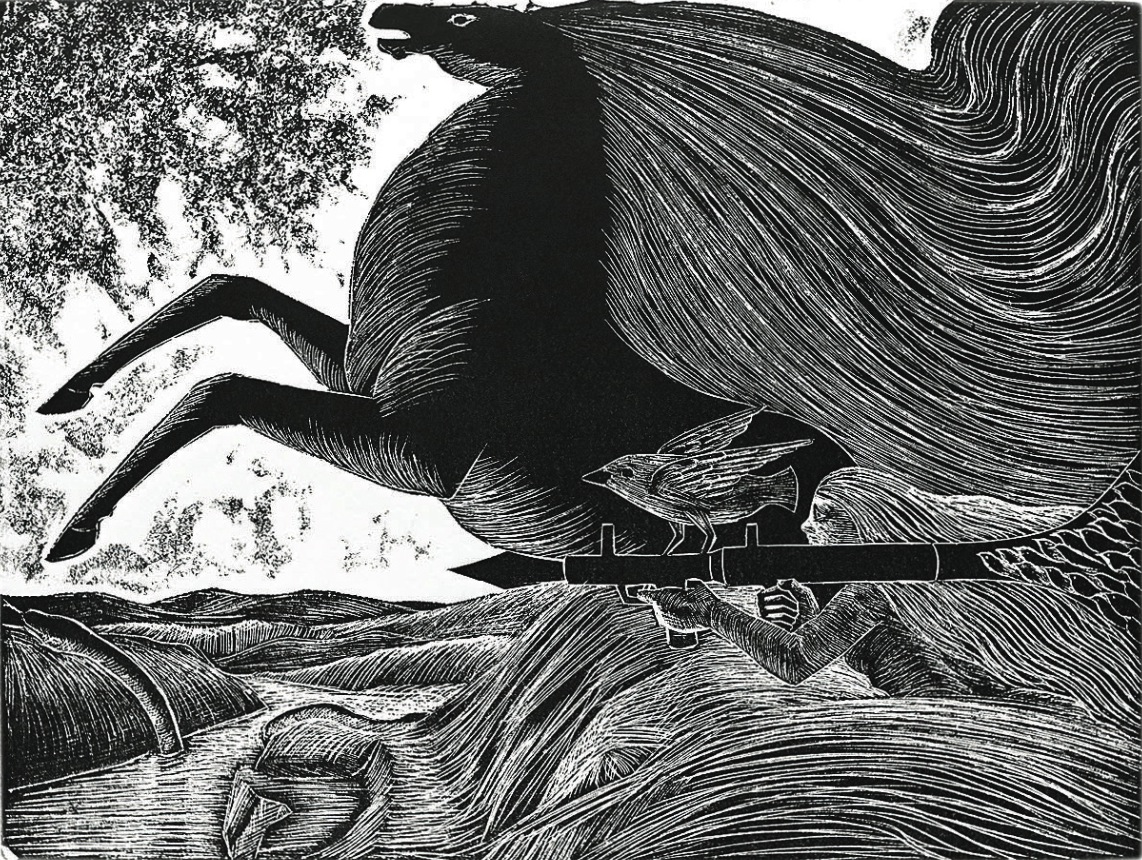

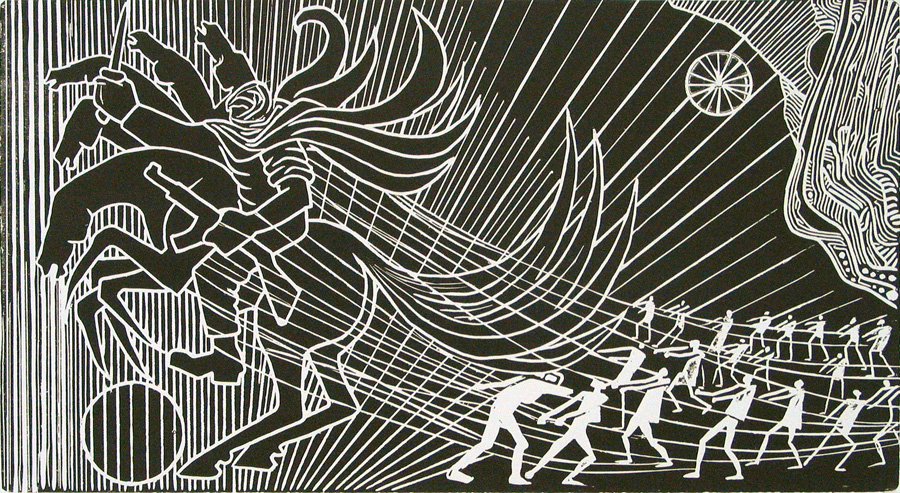

The subject matter of the Liberation artists was the revolution. They were proud to possess a cause and focused their attention thereon. Content was communicated through symbolic images combined formally in ways that Cubism and the Mexican Muralist movement established. Often the symbolic images were connected simply by being in the same space or seemingly collaged together. First and foremost in the minds of artists was the importance of connecting to the population with symbols known to them. Their paintings provide a visual lexicon of these symbols often unclear to the outsider. The foremost symbol represented the liberation struggle. Nostalgic memories of the horse in battle, and an admiration of its power in motion, earned it the status of the symbol of revolutionary motion. Moreover, the majesty of the Arabian horse symbolizes the dignity of revolutionary fighters. The horse first appeared in the work of Mustafa al-Hallaj after the 1968 victory at Al Karameh. The print “Battle of al-Karameh” (1969) shows a fighter–a woman on the ground with a heavy weapon--with a monumental horse thrusting through the sky. The long mane of the horse meanders in rhythm with the landscape below. To symbolize that the intention of struggle is to attain peace, the artist placed a dove, also thrusting forward, on the barrel of the gun, ready to take flight. Another work dating from 1990 using the horse as a symbol demonstrates his understanding of class struggle. He described the horse riders as revolutionaries and the rows of little people pulling the long strings that are attached to the shoulders of these towering figures as those who wish to stop the revolution.

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, "Battle of Karameh" (1969). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, "Battle of Karameh" (1969). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, untitled (1990). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, untitled (1990). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

Mustafa combined the new symbols of the revolution with those of ancient art and popular folklore, carefully sequencing them to contain his narratives:

I get my symbols from literature. I made a reading plan for myself in 1952 and I am still on schedule. I read everything but I concentrate on literature and folklore of the world, with the guideline that one of the mind’s eyes is a telescope and the other a microscope.[7]

Hallaj described with great absorption and celebrated the moments when ordinary objects concretize in memory and become socially useful symbols. From them he wove compelling verbal fables, which he delighted in telling as much as he delighted in his artworks.

His formal language

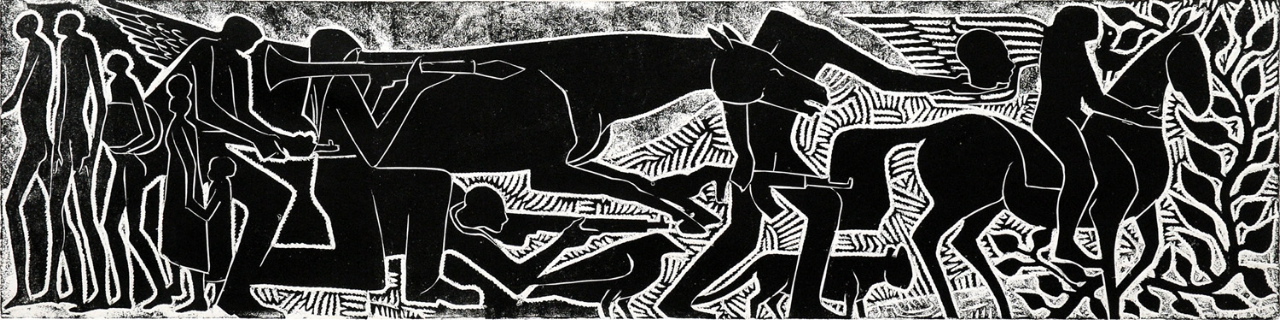

One first notices Mustafa’s capacity to draw. Each figure, hybrid or real, possesses magnificent proportion and grace although intentional distortions in scale and juxtaposition of images abound. In his prints, images of people, animals, and objects are flattened, their contours simplified, and their details removed; then they are arranged in rows in order to relate a visual story. Throughout his work, the background shapes between images, which establish negative space, are just as carefully crafted as the foreground ones that create positive space. In this, the influences of ancient Egyptian bas-relief and of Arabic calligraphy are clearly apparent given that both possess this attribute. The impact of both in Mustafa’s work dates back to his time in Luxor. An excellent example of these elements is a 1980 print that shows a row of people of all ages, weapons, and symbolic animals moving forward. It is not a group of modular soldiers of some national army but rather a social group surging forth in revolutionary struggle.

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, untitled (1980). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

[Mustafa al-Hallaj, untitled (1980). Image copyright the artist`s estate. Courtesy of the author.]

The final major work

Mustafa al-Hallaj’s major work clearly owes a great debt to Pharaonic art. The sequencing of figures and backgrounds in one image extending over ninety-seven meters actually outdoes any of the ancient arts of narration, be they Egyptian or Assyrian. This great work was begun in the mid 1990s. Engraved on masonite modules, each measuring sixty by eighty centimeters, it is a continuous horizontal image, measuring over ninety-seven meters. Mustafa had planned to continue this outpouring until the end of his life; but sadly, his life ended prematurely. He was excited that his friends were intending to submit it to the Guinness Book of Records. When I asked him for a title to the work, he mentioned that it was a “self portrait as a man, a god, and a devil” then showed me his three self-portraits in the work. “As one peruses the print, each part is called forth by the previous image,"[8] he affirmed. In one section is a figure bent at right angles from the waist, holding up a graveyard on his back. A bird that the artist called a “Hodhod,” the Afro-Eurasian Hoopoe or “Stink bird,” precedes the man. Because the bird has a smelly bump on its head, according to Mustafa, in folktales it is said that it carries its dead mother buried in its head. About the man in this particular section of his frieze he revealed:

Our friends when they die are buried in us . . . Their bodies go to the graveyard but their personalities stay with us. We Palestinian artists are an orchestra. We are one choir… We have many friends and many died. We are a walking graveyard of these personalities who left.[9]

Mustafa was honoring lost comrades in struggle as he poured decades of his experiences into this work.

[1] Interview with Samir Salameh, 26 June 2000.

[2] Interview with Mustafa al-Hallaj, 13 July 2000.

[3] Qasi Saleh, "Mustafa al-Hallaj: Artist of Legends and Happenings," Al-Thawra, 22 November 2005.

[4] Excerpted from an email exchange with Zahed Haresh on the occassion of Mustafa al-Hallaj`s death, 16 December 2002.

[5] Qasi Saleh, 22 November 2005.

[6] Interview with Mustafa al-Hallaj, 13 July 2000.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.