Beau Beausoleil and Deema Shehabi, editors. Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here: Poets and Writers Respond to the March 5, 2007 Bombing of Baghdad`s "Street of Booksellers." Oakland: PM Press, 2012

You can bomb a bookstore or ban a book,

but it will not die

You cannot kill a poem like you can a man.

Al-Mutanabbi Street will rise again.

(Sam Hamill, To Salah al-Hamdani, November 2008)

At the heart of a new anthology is the idea that the written word is invincible. The sentiment may not be altogether new, but that does not mean it has been exhausted. Far from it, as shown in the new collection, Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here: Poets and Writers Respond to the March 5, 2007, Bombing of Baghdad’s “Street of the Booksellers,” edited by Beau Beausoleil, poet and owner of the Great Overland Book Company, along with Palestinian-American poet and editor Deema Shehabi. Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here features a diversity of voices unified in their commitment to a shared project of literary activism, a shared assertion that books—and literature and knowledge—must triumph in the face of blind ignorance and fundamentalism.

To appreciate this anthology’s value, we need to remind ourselves of a disturbing fact: there is nothing inherently liberatory about literary culture. In the service of state power, literature has often been little more than a tool of propaganda. Not so long ago, writers and intellectuals from across the Arab world were conscripted—and duly rewarded—for singing the praises of the Iraqi regime, hailing Saddam Hussein as a hero. Saddam himself was heavily interested in the power of literature, penning numerous novels during his time as ruler. Nor should we forget the annual Mirbid Poetry Festival, where poets and critics, including major figures of the Arab literary left, were awarded the dubious “Saddam Hussein Medal for the Arts.” In this way, the official celebration of literature in Iraq rested on a system where writers and journalists were commissioned to produce novels, poems, and films about the dictator’s life story, the bravery of Iraqi soldiers, and more.

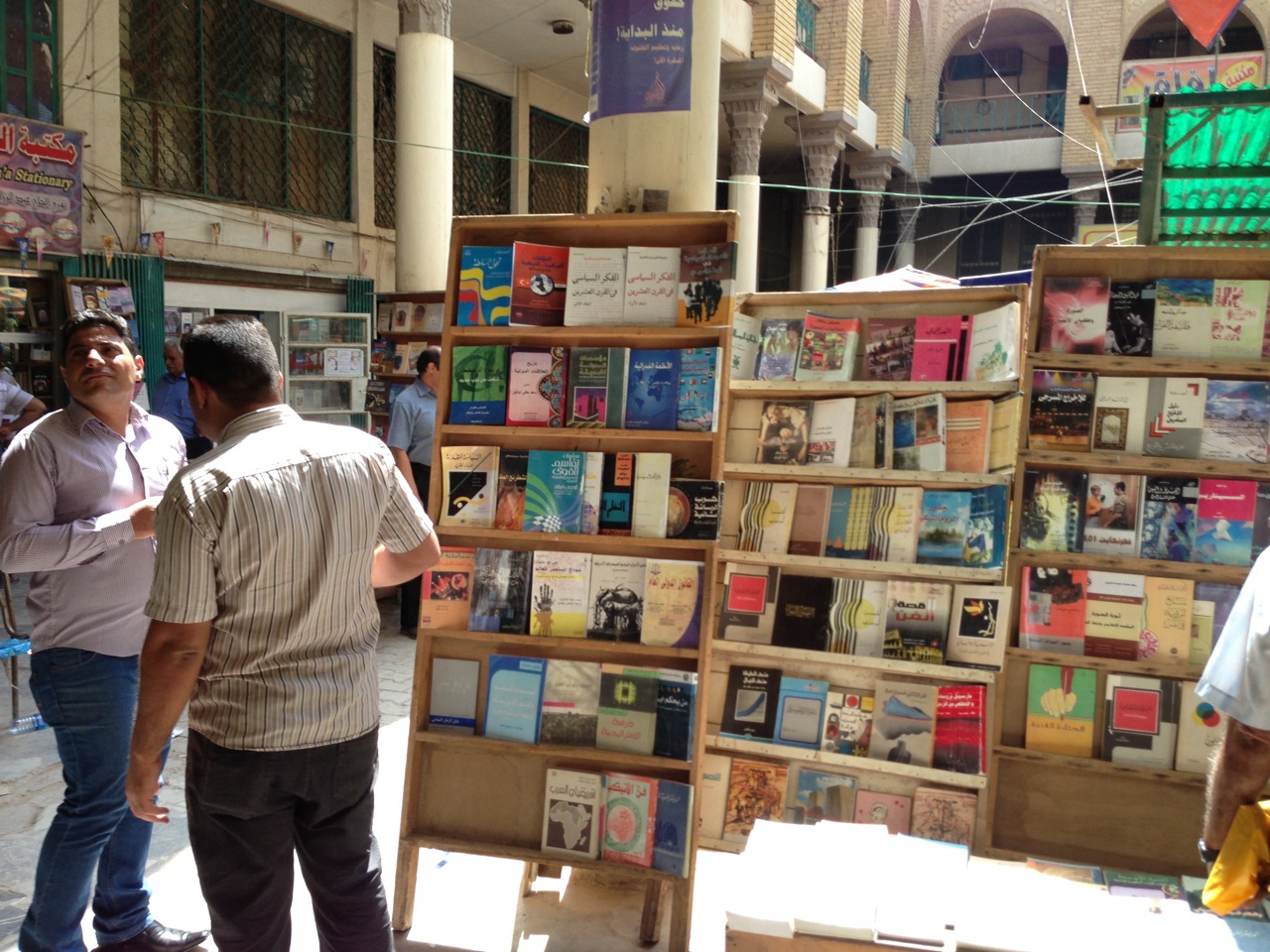

But alongside the official literary culture of Baathist Iraq, there were other literary cultures, some independent, some dissident, some radical. And this is one of the central meanings of Mutanabbi Street as an actual place. For besides being the greatest book market in the entire Arab world, Mutanabbi Street was (and is) a place for independent readers, poets, critics and activists to meet and argue. Its existence was proof of Iraq’s lively public sphere in spite of the wars, the sanctions, and the occupation.

[A bookstall on Al-Mutanabbi street today. Photograph by Elliott Colla, May 2013.]

[A bookstall on Al-Mutanabbi street today. Photograph by Elliott Colla, May 2013.]

The history of Mutanabbi Street shows how fragile the public sphere can be. Indeed, the bloody attack on the space was, in so many ways, an attack on the very proposition that Iraqis deserve a public forum, a place where people can meet to debate ideas. And thus, we arrive at the enduring necessity for the motivating force behind this collection: if writers believe that literature can play a liberatory role they must not only assert and reassert that proposition in words, they must sustain it by actions as well. Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here comes from precisely this understanding, it is a book of deeds as much as of words. Here is a group of writers engaged in a political cause, responding to an event that has touched them deeply and, in some cases, personally. Some of the contributors had a direct relationship with the famed cultural street, and so their pieces either tell a personal account of their experience with the street or are dedicated to one of its victims. The others that have never been to Baghdad are able to relate to Al-Mutanabbi Street nonetheless. They do so by drawing parallels between the attack on Al-Mutanabbi Street and other acts of violence targeting places that may stand for culture, freedom of expression or exchange of ideas.

The variety in the choice of the anthology’s contributors is also telling. By including voices from countries outside the Middle East, the anthology not only becomes richer and more diverse, but it also communicates accurately the sense of solidarity over a cause that is able to pull in people from different backgrounds, and reiterates the main theme of the project, namely that Al-Mutanabbi Street is in places other than Baghdad. It is in every place where people can pick up a book and read, exchange ideas or learn. It is in the black market of books in Pansodan, Burma and even in Alexandria’s Al-Nabi Danial Street, which was ransacked last year by the Egyptian authorities but has also risen again just like Al-Mutanabbi Street.

The same diversity in the contributors’ backgrounds means that the fight is closer to home for some writers than others. While it is easier for those writing from the comfort of a context where there are less life-threatening constraints on freedom of expression, this is not the case for others living under oppressive regimes, and risking their very lives to simply write what they feel or think. Nonetheless, both types of contributors come together in this anthology to join forces in speaking out against a common enemy for all. Knowing that there are others around the world – who have no direct gain – are sharing the concern and making their voices heard is a meaningful and much needed token of solidarity with the cultural community in Iraq.

The anthology is divided into three sections: The River Turned Black with Ink, Knowledge is Light, and Gathering the Silences, all titles that refer to the importance of writing and books. The project itself, much like the stories told within the anthology, bear testimony to how much value is attached to books and artistic culture. This global project has transformed the geographical location of Al-Mutanabbi Street, even for those who have never been there or heard of it, into a metaphor for freedom of expression. It has been able to unite voices from across the universe, to show people that even though violence is loud, literature has means of confronting it. As a counterpoint to arms, the anthology offers the arts.

The street in question is named after the famous tenth century Iraqi poet, and so it seems fit for Sinan Antoon to address Al-Mutanabbi in his contribution “Letter to Al-Mutanabbi.” In the poem, Antoon complains to the famed poet that people have yet to find a future world where they do not devour one another. Although Antoon is admittedly not very optimistic, his awareness of the power of words almost trumps his pessimism when he says that he dreams to “weave an ocean out of ink / for our myths / and out of words a sail / or a shroud / vast enough for us all.”

In “The River Turned Black with Ink,” Iraqi filmmaker Maysoon Pachachi recounts her trip back to Baghdad in 2004 after a long absence. Her visit to Al-Mutanabbi Street to shoot her documentary reveals the importance the street held in the hearts and lives of Baghdad’s population, describing books as “food of life” for Iraqis and saying that Al-Mutanabbi Street was where they went for nourishment. Three years later, when the bombing took place, she is comforted by the idea that Iraqi history follows a plotline of classical Arabic poetry where “the opening lines … are a lament over ruins. Once the lament is over, however, the poem gets on with the rest of its work.”

San Francisco-based author Lewis Buzbee tells the story of how Al-Mutanabbi Street gradually evolved from a place where travelling booksellers often passed to Baghdad’s cultural hub. In “Crossroads,” Buzbee describes what had happened the day of the bombing, “the sky rained pages and the ashes of pages. Fragments of words fell quietly to the earth…. The market had a black hole in it, where the booksellers had been; the city had a black hole, the world had a black hole.” But Buzbee is quick to note that despite the great loss, the legacy of the street and of the books themselves was far too great to be overcome by the bombers. Booksellers came back to the street and so did readers, “and the readers came to believe that their reading might be the only way to heal the black hole in the world’s heart.”

Some of the entries do not refer to the victims of Al-Mutanabbi Street alone, but also hail lesser-known soldiers of culture and knowledge in the bereaved country as heroes and heroines. For example, ‘Hearing of Alia Mohamed Baker’s Stroke’ by Philip Metres tells of a brave Basra librarian who saves the contents of a library – more than thirty thousand books – by sneaking them out in her car bit by bit, against the threat of being discovered by the occupation forces. Another poem “311 and Counting” by Lamees al-Ethari introduces the reader to some of the Iraqi academics who disappeared or were killed since the US invasion of Iraq. The official count is at 311, but she believes the real number to be even greater. In her three short stanzas numbered with the number of the victims, who remain nameless, she provides a brief description of what they did for the field of knowledge and what happened to them:

No. 313

A desk piled with last week’s essays.

19th century British Poetry.

Dark rimmed glasses silently folded

Kidnapped and still missing.

The anthology is only one installment of the larger project Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here. While most were rendered speechless and stood helpless by the scale of destruction, the loss of life, and the elusiveness of the enemy of the street of culture, and of freedom of expression and exchange of ideas in general, Beau Beausoleil spearheaded the effort Al-Mutanabbi Starts Here. It started with a project of 130 letterpress broadsides by 130 individual printers, which ultimately made their way into the collection of the Iraqi National Library and Archives in April 2013. In another attempt to bring the broadsides to the region, an exhibition will be held at the American University in Cairo in Spring 2014. The broadsides contain artwork and/or short prose or poems that somehow respond to the attack. The project members simultaneously worked on a parallel product for the project: an anthology containing the responses of scores of poets and writers to the same bombing of 2007. Even years after Al-Mutanabbi Street has officially been reopened, and after the broadside project and the anthology have been completed, the indefatigable project members continue to muster support and ideas to keep the memory of Al-Mutanabbi Street legacy alive. In a new attempt to honor Al-Mutanabbi Street and its victims, the project has a launched a call for book artists, whereby 260 artists would create three books over the course of one year as “an inventory of Al-Mutanabbi street.”

Of course this artistic project, large and far-reaching as it is, has not stopped the bombings and killings in Iraq: over 700 people lost their lives there last April, making it the deadliest month over the last five years.The contributors, whether publishers, writers or book artists, have all expressed their unequivocal support and solidarity with the Iraqi community. Their words and images are powerful, moving and have gone from one place to the next to be heard and seen, and although they cannot stop the bullets and bombs, they can do a lot more, according to contributor Fred Norman whose bio describes him as hoping “that he might someday write the words that will make the human beast humane.” Norman dedicates his entry to the famed Iraqi poet Nazik al-Malaika who died a few months after the bombing in 2007. His poem contains a clear reference to her important status as the first Arab poet to use free verse. It laments that destruction, bids Malaika to come back to Baghdad, which she left for Egypt, and laments the status of female writers in Iraq after extremism gained a stronghold in the aftermath of the US-led invasion. But it also reveals his belief that she can, through her poetry, “teach al-Mutanabbi’s cruel destroyer to play the oud, to love both night and day, both sun and moonlight, peace, to love a woman’s world.”

Until the destroyer of Al-Mutanabbi learns to play the oud, and to love peace and a woman’s world, writers and intellectuals from across the world will continue to unite and make themselves heard in every way possible. As Beausoleil says about the Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here project, “What is happening in Iraq hasn’t stopped, and so this shouldn’t either.”

![[Cropped image of Al-Mutanabbi Street Starts Here cover.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/al-mutanabbi_street039.jpg)