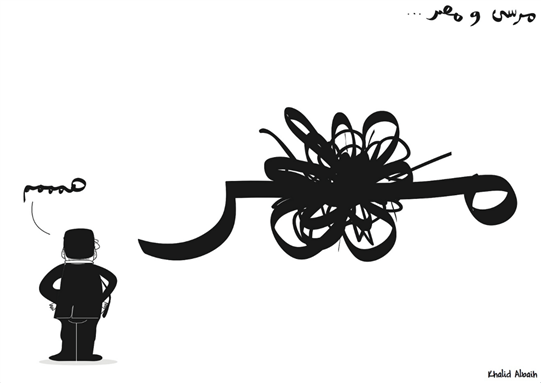

The regime produced by last year’s SCAF-Muslim Brotherhood handoff never had a chance. It was dead at birth, crushed by the many burdens it inherited and smothered under the crises of the Mubarak state and its bloated, impotent institutions. The new regime was born to face everything Mubarak left unfinished, including a deepening social crisis and a political instability that could not be checked. Despite state intimidation and repression and a succession of referendums and elections, Egypt’s political waters continued to surge.

The day after the new Constitution was ratified Mohamed Morsi officially declared an end to the transitional period. Now, supposedly, the country had a permanent Constitution, an elected president, and a Parliament to carry out legislation. The truth be told, there was no actual Parliament. Rather, Morsi’s document allowed for a transfer of full legislative powers to the Shura Council until that time when parliamentary elections could be conducted.

So is the transitional phase really over? Perhaps the revolution has been aborted, leading to a transfer of power to a broad alliance consisting of the army, intelligence services, police, and a new political class dominated by the Brotherhood. This alliance is devoted to the same repressive policies of the old July regime—the denial of civil liberties, trade union rights, freedom of information and expression, the right to assemble, and the independence of civil society. Instead, this regime favors the rituals of procedural democracy where every few years citizens make a mass pilgrimage to the voting booth. Perhaps it is more accurate to call this an authoritarian electoral system rather than a democracy.

The Brotherhood’s current problems do not stem from the organization’s authoritarianism as some have argued. Nor do they come from their zigzag dance with the revolution as others have said. The truth is much simpler: the Brotherhood joined the counter-revolution some time ago, and their departure was confirmed in the Ghariani-Shahin Constitution itself. [1]

The November 2012 Constitutional Declaration arrived in the midst of a deep political crisis and ignited the most violent period in the country’s modern history. The Ghariani Constitution was itself an amendment to the 1971 Constitution, which preserves the pillars of the authoritarian state while also denying society its basic social and economic rights and liberties. The Constitution is dedicated to centralizing and empowering the office of the president along two distinct axes: vertically, it preserves state power at the expense of the local government; horizontally, it situates the presidency above the legislative and judicial branches of government. Additionally, this constitution lays a foundation for an independent military empire by guaranteeing the autonomy of the military, and protecting it from the emergent political arena.

The Muslim Brotherhood believed that it could get through, God willing, without doing anything about the military trials and without clamping down on torture and administrative detention. The Muslim Brotherhood succeeded in passing a constitution that would allow it to establish a governing alliance with itself in the driver’s seat—and with the military, intelligence services, police, and other security branches riding shotgun. Riding in the coalition’s backseat were Al-Azhar and Salafis along with some of the marginal parties the Brotherhood picked up along the way.

This alliance proved to be fragile, balanced precariously across unresolved tensions. This was made clear during the January 2013 strike on the part of police who grumbled at having to repress others on behalf of the Muslim Brotherhood. We have also seen the tensions continue between the military and the Brotherhood presidency, along with all the talk of whether or not there might be a coup d’état.

Furthermore, there was also the tension between the Brotherhood and the General Intelligence.

Add to this the fact that the Brotherhood was never able to fully integrate state authorities into this alliance. While it managed to work with the military, intelligence services, and the police, it failed to bring the judiciary in. And this branch engaged in multiple conflicts with the executive and legislative branches which were dominated by the Brotherhood. All this, despite the fact that the judiciary, in its entirety, stood in the way of efforts to bring legal justice for the January Revolution. First under Abdel Meguid Mahmoud, then under the Muslim Brotherhood’s Attorney General, the courts managed to squash the prosecution of a whole range of cases, from the killings of demonstrators to civil society restrictions, labor strikes, and so on. These tensions crept into the nascent relationship between the Brotherhood and Al-Azhar during debates over the issue of Islamic bonds, and again during the outbreaks of food poisoning in the Al-Azhar dormitories. This same tension spread across a range of state agencies, each of which has hyper-local ways of conducting its business. The entire state bureaucracy resisted the organization as it attempted to “brotherize” office after office, and managed to preemptively stop the Morsi government as it took on the administrative apparatuses of the state.

The Brotherhood did not just inherit the Mubarak or July 1952 regime. It did not just inherit the old system’s authoritarian relationship to society, or the same old composition of the former ruling coalition. What it inherited was also failure. What I mean by this is the state’s inability to represent public interest, its inability to use the legal mechanisms of coercion to manage the affairs of society. Without that legal power, there is nothing that distinguishes the state from other social institutions. A state’s authority emanates from this power, and nowhere else.

We can talk about the failure of the new-old regime vis-à-vis four issues: chronic economic crisis; persistent social strife; second-generation protest movements; an unmanageable state. These are the same issues that drove the country to revolt against Mubarak in January 2011.

First, there was the regime’s inability to manage the chronic economic crisis. This was passed on to the Brotherhood from Mubarak who, in his last years, oversaw massive fiscal deficits. These increased as a result of the state’s inability to reduce expenditures. This crisis manifested itself in an exorbitant political cost due to the reduction of subsidies and liberalizing fuel and food prices on the urban poor and middle class. Further exacerbating this situation was the state’s inability to increase tax revenues. This was due to the weak administrative state and inability (or lack of will) to impose taxes on large capitalist interests. Add to these the problems associated with the transition itself, including the severe mismanagement of the economy first by SCAF, then by the Morsi government. These months were also marked by diminishing growth rates. Rates on both domestic and foreign investments declined seriously. What was more alarming was the depletion of the country’s foreign reserves. These reached a dangerous low in December 2012, when the Central Bank was no long able to supply the state with what it needed to pay for essential food and fuel imports. Similarly, it withdrew supports for the Egyptian Pound.

Second, the Morsi regime was unable to grapple with the country’s ongoing social and economic protests—the strikes, the sit-ins, and demonstrations for better living conditions and real wages. When the state security collapsed in January 2011, the rate of monthly protests rose from one hundred seventy-six in 2010 to two hundred eleven per month in 2012, and then dramatically increased to nine hundred twenty-seven in 2013.

Third, the regime similarly failed to handle the political protests that began under Mubarak in 2004. Following the March 2011 referendum, the Brotherhood—in negotiation with SCAF—created a political system that was based on an extremely narrow concept of democracy. The focus was entirely on electoral procedures, and did not speak at all to political considerations of rights and civil liberties. It was mute on issues of freedom of speech and expression, and silent about the right to association, whether in civil groups or union.

Since the November 2012 Constitutional Declaration, protests, small and large, have filled the scene. We can attribute them to a broad spectrum of political coalitions, youth, and revolutionary groups which cannot find a fixed place in the new political sphere following the overthrow of Mubarak. At the same time, these groups rightfully expected that the new political system would create a sphere for the rights and freedoms they fought for. What they got instead was a new authoritarian ruler who claimed, on the basis of elections, to be more legitimate than his predecessor. The same protest movements that struggled against Mubarak would then turn to confront the Muslim Brotherhood. This is a key feature in the crisis of the Brotherhood’s regime, it succeeded in creating a wide range of political actors from the new political domain. These actors have been betting that, if they invested enough in maintaining the level of crisis and political turmoil, the system might collapse by itself, or that the army to return to power, or they might even succeed in staging a popular uprising against the new regime.

The fourth and final element is the Brotherhood’s inability to manage the authoritarian ruling coalition. In my opinion, the Brotherhood has not been oscillating between the revolutionary and counter-revolutionary camp, for the simple reason that the revolution was abandoned despite continued pressure from the bottom, and this has meant that activists lack the power to change the situation. The Brotherhood’s challenge now has to with its inability to manage the counter-revolutionary camp and their failure to form a political-administrative class to run the country. Even though Brotherhood supporters have confidence in their governing abilities, their members usually lack sufficient expertise. And there is nothing the Office of Divine Guidance can do about that, even when its members are loyal.

Experienced people within the political class and the state system are not part of the Brotherhood. At present, these experienced, talented people have been relegated to marginal roles in the governance of the country. Add to this, the fact that the Brotherhood lacked political imagination and, in the end, was tied to the old regime through the security services, the military bureaucracy, and sectors of big business. These deals tied the Brotherhood to a failed and corrupt state bureaucracy that was not just unwilling to implement reform, but was disloyal too boot.

All this exposed them to criticism from revolutionary forces that—pointing to the Brotherhood’s weak performance and ever deteriorating living conditions in the country—still maintain the ability to press effectively against their rule.

At the core of this dilemma was the Brotherhood’s lack of will to gamble by restoring the old July state in its authoritarian guise and the Mubarak state with its neoliberal predilections. This was rooted, no doubt, in the fact that the Brotherhood was nothing more than a religious cult clinging to the idea it possessed the last word in matters of interpretation, as the late Hosam Tamam once put it. To do so would have meant the new rulers would have been up against the same forces that took on Mubarak in his last years, whether directly (as in the case of the youth protest movements), or indirectly (as in the case of the labor and civic protests). And they would have had to do it with fewer financial resources than Mubarak, and less reliance on a loyal set of repressive forces (in the police, army and intelligence). In that sense, the Brotherhood was always more like the final chapters of the last book than the first chapters of a new one.

[This article was published in Arabic on Jadaliyya on 19 June 2013. It was translated by Jared Markland and edited by Elliott Colla. It is part of a two-part series. Click here to read the second part. Click here to read the Arabic version.]

.jpg)