[Part one of this series can be found here.]

[Part two of this series can be found here.]

Those who constituted the Occupy Gezi movement comprised an eclectic array of constituencies, each bearing its own list of grievances and demands. So while they came together for various social, cultural, political, and environmental reasons, it was largely their shared contempt for Erdoğan that brought them together initially. Offering witty commentary on these strange bedfellows, one digital image, emulating a cellphone commercial, shows two hands reaching for each other with a caption reading: “Tayyip, Connecting People.”

So who were these Gezi Park protesters? They were urban planners, environmentalists, soccer fans, artists, musicians, feminists, gays and lesbians; they were Kemalists, nationalists, communists, anarchists, members of workers’ parties, and anti-capitalists; they were Kurds, Armenians, and Alevis; they were animal-lovers and vegans; they were secular and religious; they were children and retirees. Paying tribute to this consortium, banners of political groups crowded the façade of the Ataturk Cultural Center as if it was a Facebook home page; posters of multiple demands were produced and hung all around the park; a “Wishing Tree” made of metal scraps was covered with post-it petitions; and a banner on the makeshift “Museum of the Revolution” in Gezi Park bluntly declared “Here there is every color.”

[Left: Atatürk Cultural Center, Taksim Square, 7 June. Right: Posters listing the demands of the

Taksim Solidary Group, Gezi Park, 9 June. Photos: Christiane Gruber)

[Left: Wishing Tree, Taksim Square, 10 June. Right: “Here there is every color,” Museum

of the Revolution, Gezi Park, 10 June. Photos: Christiane Gruber)

Although it is often reiterated that the Occupy Gezi movement is larger than a park, environmentalists remained at the forefront and constituted a core block in the protests. Within Gezi Park, the greens taped signs to the trees, urging passers-by to “Listen to your conscience, don’t kill me.” Other environmentally conscious activists created their own tailor-made messages, equating uprooted trees with other deracinated freedoms in Turkey. For example, one actor-artist warned: “Don’t touch my stage, my art, my Inci, and my tree.”

[Left: “Listen to your conscience, don’t kill me,” Gezi Park, 2 June. Right: “Don’t touch my stage,

my art, my Inci, and my tree,” Gezi Park, 10 June. Photos: Christiane Gruber.]

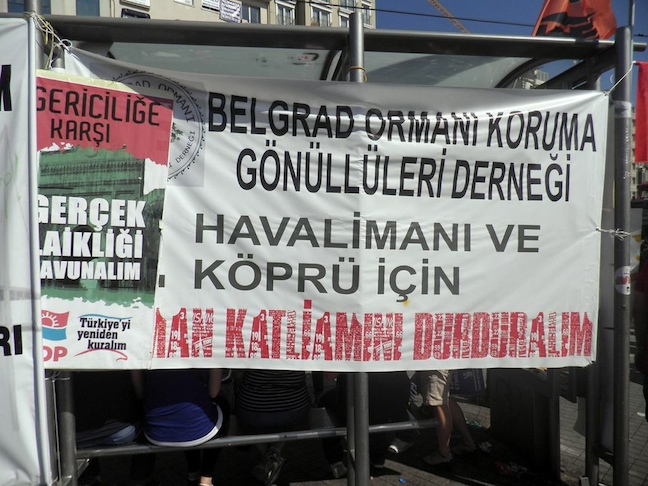

Saving Gezi Park from destruction was certainly not a one-off effort; on the contrary, it forms part of a wider desire to protect nature and the environment in the wake of unbridled growth and urbanization, especially in and around Istanbul. Other green spaces are equally at risk, especially the northern (Belgrade) forests bordering the Black Sea, out of which an estimated one million trees will be cut in order to make way for an enormous new airport and the third Bosphorus bridge. In Gezi Park, such state-imposed violence against nature was analogized to the government’s steady eradication of citizens’ rights, wherein activists declared that “one tree died, one people awoke” and warned that “the tree lives, the government dies.” Graffiti spray-painted in the park even threatened Erdoğan with a vengeful quid pro quo: “You destroy our park, we burn your palace.”

[Sign in support of the protection of the Belgrade Forest and against the new airport and third

Bosphorus bridge, Taksim Square, 9 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber]

[“One tree died, one people awoke,” Gezi Park, 5 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“The tree lives, the government dies,” Gezi Park, 2 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

Along with the environmentalists came a host of other groups. Among them were left-leaning secularists; many were politically unaffiliated, while others were staunch Kemalists or self-described warriors of Atatürk. The image of the founder of the secular Turkish Republic was thus ubiquitous in the Occupy Gezi movement. The legacy of Atatürk was redeployed by some as an antidote to the AKP’s vision. As a result, his image appeared on t-shirts, banners, pins, and stickers, asking protesters to not “bow their necks” to “AKP fascism.” Atatürk also was reclaimed through the sculpture and architecture of Taksim Square, in particular the 1928 Republic Sculpture and the Atatürk Cultural Center, itself a prime example of Turkish modern architecture.

[Left: Atatürk and Che Guevara, Taksim Square, 4 June. Right: Republic Sculpture, Taksim Square, 1 June. Photos: Christiane Gruber.]

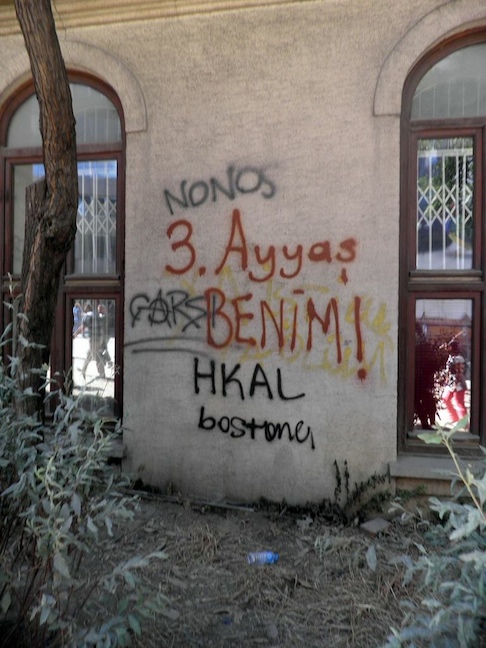

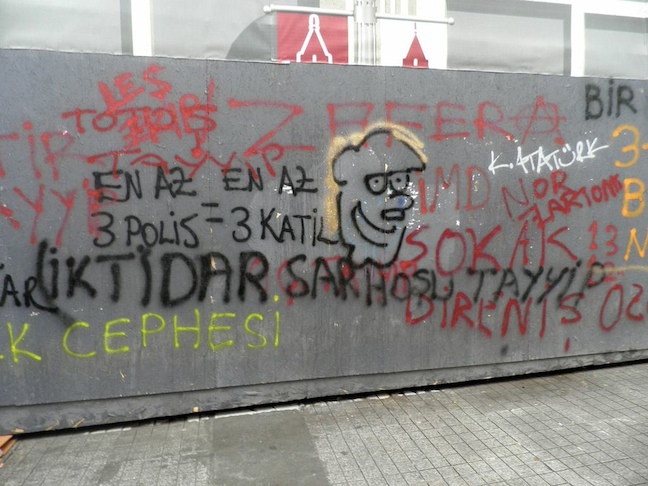

In one of his recent speeches defending the newly passed ban on alcohol commercials and sales in shops from ten pm to six am, Erdoğan rhetorically asked why one should follow the customs of “two drunkards” (iki ayyaş) rather than the prescriptions of religion. Opponents were incensed by Erdoğan’s reference to Atatürk and Inönü as alcoholics; thus republicanism and the consumption of alcohol became entangled, yielding new slogans and images. In a number of graffiti, demonstrators warn Erdoğan that he has banned his last beer while proudly declaring: “I am the third drunkard.” Like the noun “bum” (çapulcu), the pejorative term for “drunkard” (ayyaş) was adopted as a mockingly self-censorious honorific title. It was deployed in double support of secular law and personal freedom. For these reasons, protesters dedicated the demonstrations to Erdoğan’s “honor,” while delivering a buffoonish caricature that resembles the maladroit Homer Simpson. Demonstrators also turned charges of drunkenness against the accuser himself, labeling Erdoğan as “intoxicated with power.”

[“I am the third drunkard,” Gümüşsuyu, 9 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“To your honor, Tayyip,” Istiklal Avenue, 1 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“Tayyip, intoxicated with power,” Istiklal Avenue, 2 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

Besides enraging the secular youth, the AKP government has marginalized members of the LGBT community. One of the goals in redeveloping Taksim may have been to “tame” or even eradicate the LGBT presence in the area. Taksim is home to the gay and transsexual community, along with the adjoining neighborhood of Tarlabaşı, also undergoing massive redevelopment. LGBT members have been at the forefront of the Gezi Park resistance, with the rainbow-peace flag becoming a key visual symbol of the movement. Within the park, they carved out a “block,” within which they requested legal protections as well as a halt to the “massacre of law.” Moreover, as a retort to the state’s position on homosexuality, they also pinned up signs declaring: “Trans-identities are not an illness.” They also produced a variety of “lollipop” signs stating simply that “gays exist” and “lesbians exist.” Turning a homophobic curse on its head, other lollipops asked the cavalier question “So what that we’re fags?” These signs joined many others (also produced in Kurdish, Arabic, and Armenian) carried by about twenty thousand individuals who took part in the LGBT March on 30 June. With Gezi occupiers and other supporters in tow, participants in the march chanted, “This is only the beginning, the struggle goes on,” while holding signs declaring “We’re resisting” and “We’re everywhere, get used to it.”

[Left: LGBT Block, Gezi Park, 6 June. Right: Sign asking for a halt to the massacre of law, Gezi Park, 6 June. Photos: Christiane Gruber.]

[Left: “Trans-identities are not an illness,” Gezi Park, 10 June. Right: “Lesbians exist,” Gezi Park, 2 June. Photos: Christiane Gruber.]

[Left: “So what that we’re fags?” Gezi Park, 2 June. Right: LGBT March, Taksim Square, 30 June. Photos: Christiane Gruber.]

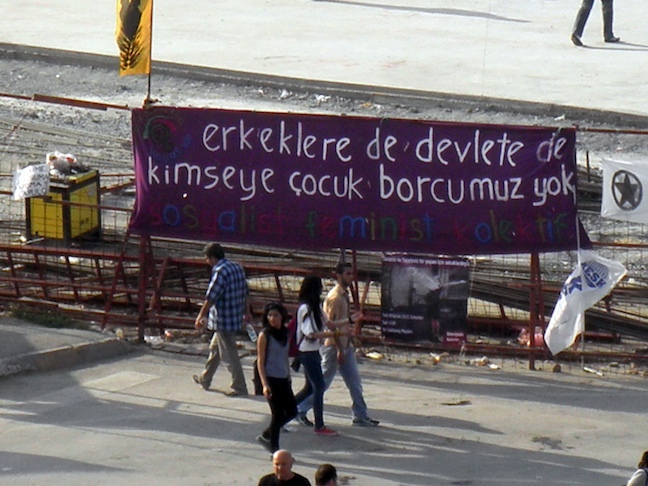

In recent years, Erdoğan has assaulted women’s rights from every possible angle. It is therefore not surprising that women took to the streets, making up fifty-one percent of the protesters and calling for a “Revolution Girl Style Now!” Within Gezi Park, feminists erected a booth, issued an official statement, and produced brochures and paraphernalia in support of women’s rights. In their banners, feminists exclaimed that “we do not owe children to men, the government, or anybody,” while in the streets they marched “for a Tayyip-free and harassment-free life” (a reversal of the government’s campaign for a smoke-free environment).

[“Revolution Girl Style Now!” Istiklal Avenue, 12 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“We do not owe children to men, the government, or anybody,” Taksim Square, 7 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“We are in the streets for a Tayyip-free and harassment-free life,” Galatasaray Square, 8 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

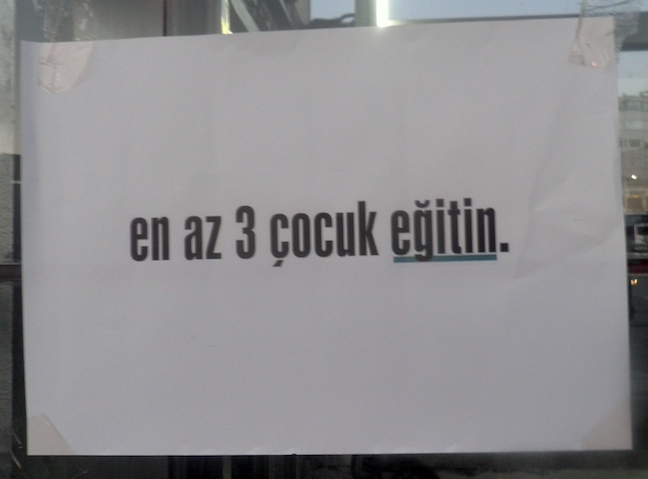

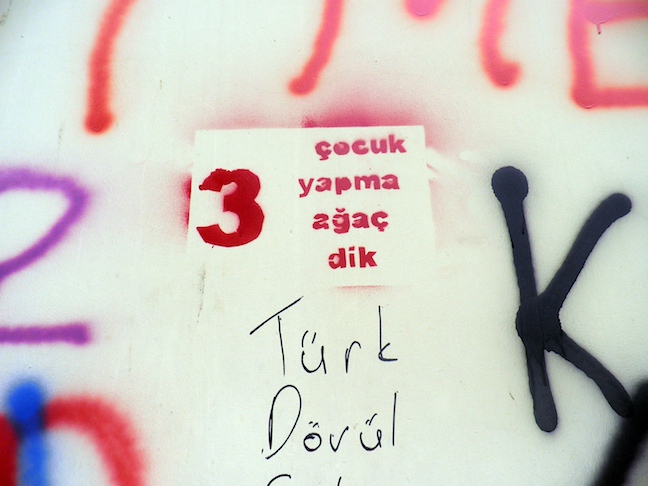

Erdoğan’s request that women have “at least three children” (en az üç çocuk) was also turned against him: in both graffiti and t-shirts, demonstrators facetiously asked the prime minister: “Do you really want three more children like me?” In others, the expression “at least three” was creolized with other socio-political issues, yielding graffiti reading “at least three beers” (alcohol ban), “at least three cats” (animal protection), and, commenting upon Turkey’s controversial school reforms, “educate at least three children.” Finally, stressing the need for population control and environmental protection, other graffiti offered the imperative: “Don’t make three children, plant three trees.”

[White t-shirt: “Do you really want three more children like me?” Gezi Park, 6 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“Educate at least three children,” Taksim Square, 20 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“Don’t make three children, plant three trees,” Taksim Square area, 12 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

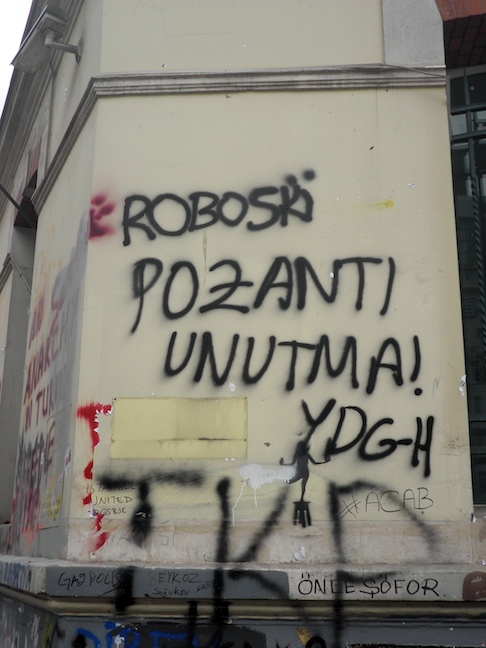

Taking a cue from one of Erdoğan’s more obscene analogies, feminist issues also cross-referenced Kurdish grievances. The feminists in Gezi Park and those who marched on Istiklal Avenue produced signs that read: “Abortion is a right, Uludere is a massacre.” These signs provided a retort to Erdoğan’s proclamation that “every abortion is an Uludere,” a statement widely seen as a tactic to divert attention from the 2011 Roboski (Uludere) massacre, when thirty-four civilians, most of them Kurds, were killed by Turkish F16 jets. With a general silence looming large, Kurdish participants in the Gezi protests pleaded with the general public through their graffiti, asking them to not forget the injustice and trauma of Roboski and the Pozantı prison revelations, in which Turkish police are accused of having viciously tortured and raped young Kurds.

[Left: “AKP, take your hands off my body” and “Abortion is a right, Uludere is a massacre,” Galatasaray Square, 8 June.

Right: “Don’t forget Roboski and Pozantı,” Taksim Square, 12 June. Photos: Christiane Gruber.]

Although Kurds were not among the most vocal demonstrators, they were present in Taksim nevertheless. In an 8 June march up Istiklal, members of the Kurdish Peace and Democracy Party (BDP) carried banners of imprisoned Kurdish leader Abdallah Öcalan; they also carried a large banner, telling Erdoğan to take the name of his bridge and get lost. Besides rebuffing the prime minister’s infamously boorish expression “Take your mom and get lost,” the BDP banner extends the Kurdish platform to criticize the third Bosphorus bridge and its name.

[“Kurds” (Kürtler), graffiti in progress, Taksim Square, 2 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[Banners of Abdallah Öcalan, Galatasaray Square, 8 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“Take the name of your bridge and get lost,” Galatasaray Square, 8 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

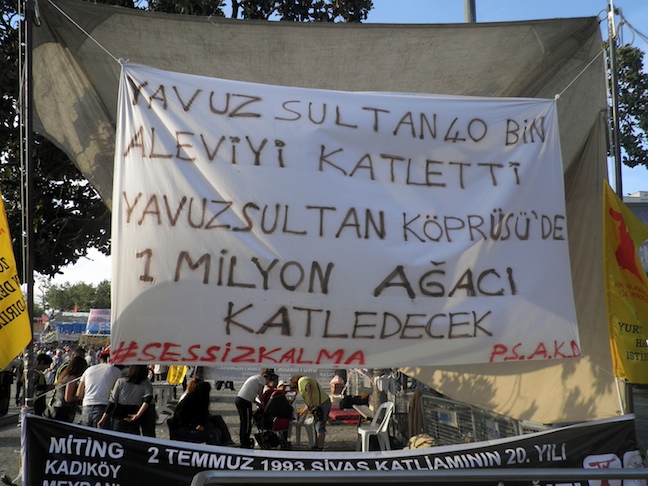

While the greens consider the third bridge an impending environmental disaster for Istanbul, its naming after Yavuz Sultan Selim is opposed by members of the Alevi community. Like other groups, the Alevis joined the Gezi movement with a ready list of grievances in hand. A group of Alevis from Sivas marched up Istiklal on 9 June, holding a large-scale banner citing a wise saying on honor and righteousness uttered by Imam ‘Ali. Other Alevi banners in Taksim depicting Imam ‘Ali opposed the name of the third bridge while also supporting both environmental protection and a pluralistic democracy. One banner, for example, exclaimed that the “Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge is a bridge of massacre,” while another drew an even more precise comparison by stating that: “Yavuz Sultan killed 40,000 Alevis. The Yavuz Sultan Bridge will kill one million trees.”

[Left: Banner depicting Imam ‘Ali, Istiklal Avenue, 9 June. Right: Banner showing Alevi opposition to the naming of the third bridge

and supporting both environmental protection and pluralistic democracy, Taksim Square, 9 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[Left: “Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge is a bridge of massacre,” Taksim Square, 10 June. Right: “Yavuz Sultan killed 40,000 Alevis.

The Yavuz Sultan Bridge will kill one million trees,” Taksim Square, 8 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

Other religious groups were also present on the Gezi scene. By 2 June, a banner in Gezi Park announced the arrival of the Anti-Capitalist Muslims with a Qur’anic verse (42:39) inviting the righteous to defend themselves against tyranny. The banner’s logo—a large “No” (La) written in Arabic script—could be found scrawled on walls within the park, alongside other caveats to not forget Reyhanlı, where a car bomb that killed civilians served as a response to Turkish embroilments in Syria. Besides recalling Bahia Shehab’s “No” series studding the streets of post-2011 Cairo, the multiplied “Las” positioned the Anti-Capitalist Muslims against the AKP.

[Left: Banner of the Anti-Capitalist Muslims, entrance to Gezi Park, 2 June. Right: Two large “No`s” (La) written in

Arabic script and graffiti imploring “Do not forget Reyhanlı,” Gezi Park, 2 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

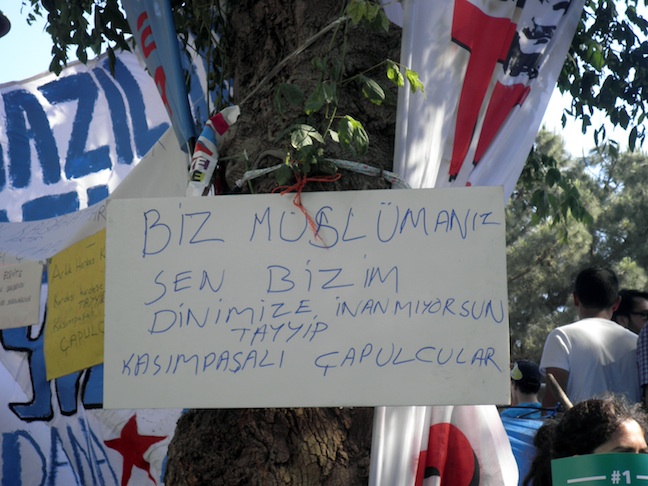

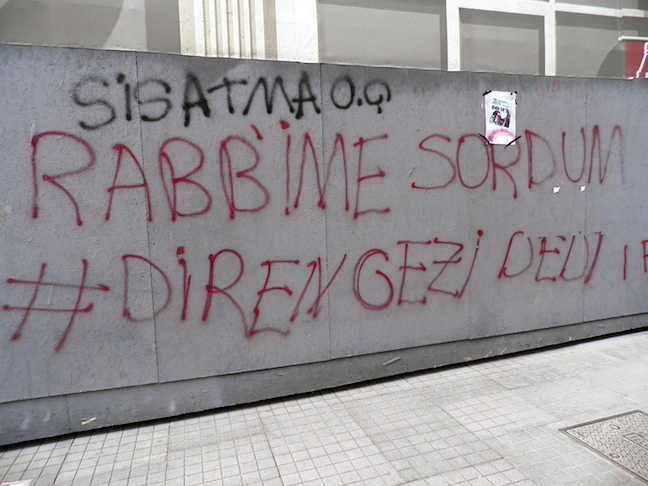

Within a week’s time, the Anti-Capitalist Muslims became a key presence at Gezi Park, where they led prayers, celebrated miraç kandili, and provided a prayer space in a tent-mosque erected at the very entrance of the park. While the Anti-Capitalist Muslims were the most visible religious-political group in the movement, many other unaffiliated Muslims were also present: some were “Muslim bums” from Kasımpaşa, Erdoğan’s childhood quarter close to Taksim, who blasted the prime minister for not “believing in our religion.” Yet another demonstrator sprayed graffiti on Istiklal Avenue confiding to passers-by that: “I asked my Lord, and He said #direngezi,” invoking the Twitter hash-tag for the Gezi Resistance.

[Tent-mosque of the Anti-Capitalist Muslims, entrance to Gezi Park, 10 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“We are Muslims. You do not believe in our religion, Tayyip. From the bums of Kasımpaşa,” Gezi Park, 9 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

[“I asked my Lord, and He said #direngezi,” Istiklal Avenue, 4 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

Many other groups and individuals contributed to Occupy Gezi efforts. A variety of political parties, universities, unions, and soccer fans added new dimensions to the movement’s politico-social crystallization and its visual emergence. Whether such a multiplicity of voices and mobilization of creative energy can be consolidated into a cohesive opposition remains to be seen. What can be said at present, however, is that the Gezi resistance has offered an alternative vision, generated in no small part thanks to an explosion of oppositional slogans and images.

This vision seeks to ensure a ground-up democratic process, rejecting the current majoritarian-cum-authoritarian top-down system of rule. Taksim Square and Gezi Park were the most important staging grounds for this politico-cultural occurrence to take shape. Here, in the bustling heart of Istanbul, a new semi-autonomous community thrived during the first two weeks in June, christening itself the “Taksim Commune” and “Democracy’s Atelier.”

[Left: “This way to Taksim Commune,” Gümüşsuyu, 9 June. Right: “Democracy’s Atelier,” Gezi Park, 6 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]

Even after the police raid of Gezi Park on 15 June, people`s assemblies did not come to an end: they have continued and multiplied as direct democracy forums within public parks in cities across Turkey. Demonstrators have not vanished either: they have found new ways of continuing their protests by marching, standing still, and placing empty shoes in public squares to commemorate those who lost their lives in the protests. Gezi Park may be empty right now, but protesters will continue to occupy public space until they are offered a real forum for democratic debate.

[Left: Shoes commemorating the four men who died during the Occupy Gezi protests (1-20 June), Taksim Square,

20 June. Right: “Occupy Public Space,” Taksim Square, 10 June. Photo: Christiane Gruber.]