I write this not as the human rights defender I have become known as, but rather as the daughter of Bahraini parents who painted an ideal image of Bahrain for us since we were children growing up in exile in Denmark. This reflection was prompted following my recent attempt at traveling to Bahrain when British Airways prevented me from boarding my flight at the orders of the Bahraini government. The realization that I am no longer in self-imposed exile triggered images of the Bahrain that my parents described while in exile, in comparison to the images I have of Bahrain now.

Born in Syria to activist parents who were forced to leave Bahrain, and then living in Denmark, I did not know the Bahrain my parents reminisced about until we moved there when I was fourteen years old. The Bahraini community in Denmark was rather small, comprised of twenty-one families. Our parents did everything they could to make sure we were raised in an environment that preserved our Bahraini identity. Once a week we gathered at the Bahraini-Danish Society, where they organized programs for us about Bahraini culture and society. We memorized and sang songs about loving Bahrain; we put on plays from old Bahraini series, and we celebrated religious and national events.

[Image of the author dressed as a fisherman during a play. Image provided by author.]

[Image of author with younger sister dressed in Bahrain traditional clothes. Image provided by author.]

Bahrain in our minds was a paradise—the land of a million palm trees, of natural freshwater springs like Ain Athari, and a burning sun. My parents recall making what was once the long journeys (now a ten minute drive) to Athari to swim in the natural spring, and sit under palm trees to seek shade from the sun. My grandfather had a fishing equipment store at a time when the fishing industry thrived and had not yet been monopolized by the ruling family. Bahrain was an image of pearl divers and Bahraini men in their local attire catching fish. Naturally, we also learned of Al Khalifa’s repression in Bahrain. My uncle was a political prisoner, like thousands of others during the 1990s. Torture was systemic and systematic, and human rights violations were rampant. People were tortured to death, and we grew up hearing stories of how many individuals and families were forced into exile, their citizenships revoked. We knew Ian Henderson then as the British man who set up “modern” and more efficient torture methods that the regime used, and Adel Fulaifel as his right hand man.

Throughout our childhood, my father, Abdul-Hadi Al-Khawaja, spent all of his time fighting for the rights of political prisoners through the Bahrain Human Rights Organization, which was based in Copenhagen. He traveled often and spent much time writing reports and statements detailing the situation of political prisoners in Bahrain. At an early age, he and my mother taught us that having a conscience is what makes you human, and that the greatest achievement in life is helping others. My mother, Khadija Al-Mousawi, taught us Arabic, and made sure we watched Arabic cartoons. I have a distinct memory of her sitting on a prayer mat, with tears rolling down her cheeks after speaking to family members she had not seen in years. Both my mother’s parents passed away while she was in exile. My grandmother’s last wish had been to see her youngest daughter. When my paternal grandfather died in 1996, it was the first time I saw my father cry. He packed his bags the next day and left for Bahrain despite the imminent risk of arrest and torture. For approximately a week he was held at the airport, and we waited for news of whether he would be placed under arrest, or sent back to Denmark. He was eventually sent back.

[Image of the author`s parents. Image provided by author.]

Several years later, in 1999, the old Emir died and his son, Hamad Al Khalifa, took over the reins of power. He started talking about change, and a real constitutional monarchy. Central to that promise was allowing people in exile to return home, and reinstating their citizenships. He allowed the release of political prisoners and the return of those in exile, but the rest were nothing but empty promises. He unilaterally changed the constitution in 2002, creating an absolute monarchy, announcing himself as King, and giving impunity to those who had been involved in crimes of torture and extrajudicial killings. He also reappointed his uncle as prime minister. The latter had held that position since 1971 and is known as being one of the extreme hardliners in the ruling family.

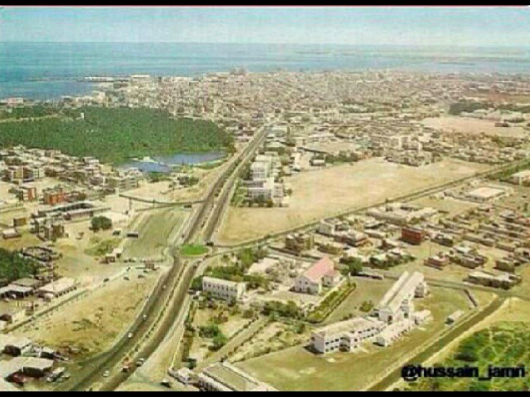

When we moved to Bahrain in 2001, my parents drove us around and showed us the places they grew up in. I could see the look of love in their eyes, but also of disappointment in how everything had changed. The regime had gotten rid of most of the palm trees, and many of the natural freshwater springs had dried up. I remember hearing my father say that if the opposition in Bahrain did not move quickly to preserve Bahraini heritage sites, there would not be much left to save in fifteen to twenty years. I did not quite understand what he meant at the time.

In the ten years I lived in Bahrain, I came to understand the meaning of my father’s alarm. Land reclamation was rampant, and Bab Al Bahrain [Gate of Bahrain] was no longer an entry point to the island. Instead of investing in the underdeveloped parts of Bahrain, the ruling family busied itself in moving landmass from certain areas of the main island and dumping it into the sea to create more land space. The prime minister is known for buying the financial harbor built on reclaimed land for a symbolic amount of one dinar. Other land reclamation was turned into housing developments that only the very rich could afford, mainly involving the crown prince. The process killed much of the marine life. I spoke to an employee at a Bahraini ministry who told me he was part of a group responsible for breeding different types of fish. Their goal was to release the fish into the sea to make up for the ones that had died due to land reclamation. However, they all died within a week of living in these waters. The employee told me the ministry was not allowed to report this in its official records.

Land reclamation, with its devastating environmental consequences, was never intended to help the Bahraini economy. Instead, members of the ruling family who owned the land pocketed all the profits. In 2009, I left Bahrain for a year on a Fulbright Teaching Assistant program in the United States. Upon returning, I visited one of my favorite areas in Bahrain, the beach near the Al Fateh Highway, which until 2009, had been untouched. Within a year, the water was no longer visible. Dumped sand covered the site of the new reclamation project. Um al-Subban, one of Bahrain’s islands that was renamed “Mohammadiya Island” after the prime minister’s brother Mohamed Bin Salman claimed ownership of it, is a perfect example of what Bahrain could look like.

[Image of Om AlSubban Island. Image provided by author.]

In the past two years, the ruling family also demolished a number of mosques. Some of them had existed in Bahrain longer than the AlKhalifa’s have. This was a form of persecution against the Shia majority in Bahrain and part of a wider sectarian crackdown aimed at punishing those demanding civil rights. Similar to the land reclamation measures, the demolition of these mosques and the pearl monument was political and served the goal of limiting dissent in public spaces. This process was two-fold: in addition to the politicized nature of demolishing public spaces, the linguistic and physical replacement of these landmarks and historic sites targeted and marginalized the Shia population. For example, after demolishing the Pearl monument, the regime renamed it Al Farouq Junction, which upholds a sectarian narrative of Islamic history. Similarly, after demolishing one of the historic Shia mosques, the regime announced that it would be turned into a public park, which neutralizes the space and erases Shia history in Bahrain.

Changes to the make-up of the population and their impact on the living conditions of both locals and migrants are also telling. The historic souq in Manama, for instance, has become home to thousands of migrant workers. Locals call it the Bahraini Mumbai. Underpaid and overworked, migrant workers brought in mainly by members of the ruling family began to overpopulate Manama, tilting the demographics of the small state. Bahraini citizens are only allowed to inhabit three of the thirty-three islands that comprise Bahrain. The central of these three islands is usually shown as the map of Bahrain. Therein, access to only the upper half is allowed for Bahraini citizens. The ruling family privately owns the rest, some of which it has given away as gifts to other ruling monarchies in the Gulf. The majority of the main island’s coastline is also privately owned, making Bahrain the only island in the world where ninety-seven percent of its shoreline is privately owned. The remaining three percent open to the public is undeveloped, and usually very dirty.

Poverty and unemployment are visible in oil rich Bahrain, with people living in rundown homes that are at threat of collapsing. Unpaved roads are prevalent in those residential areas, where the absence of a sewage system left those areas flooded when it rained. Instead of investing in basic infrastructural work there, the regime built bridge after bridge to overpass overpopulated roads and neighborhoods. Although the rulers stripped many of the island’s original inhabitants of their lands, some continued to work their land despite not owning it anymore. This and other forms of corruption are widespread in Bahrain and is a topic of discussion, and satire, at many private gatherings. A recurring joke is that many projects are often granted millions of dinars and yet are delayed halfway through the process because by the time they were passed on to the contractors, the majority of the money was gone.

[Image of a village in Bahrain. Image provided by author.]

Bahrain’s rulers treat the country they took over approximately 230 years ago as a typical business model. To protect their investments from the people of Bahrain, they have brought in tens of thousands of Sunni mercenaries from countries such as Pakistan, Jordan, Syria, and Yemen to maintain their authoritarian hold on power. This also serves a purpose of changing the demographics of Bahrain from a Shia majority into a Sunni majority, as the regime only allows for the political naturalization of Sunnis. Through their membership in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Bahrain’s rulers have forged alliances with other Gulf monarchies, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Such alliances have shielded Bahrain from international scrutiny and accountability. Bahrainis often complain that Bahrain is not Al Khalifa’s country and Bahrainis are not their people. They accuse the rulers of treating the country they conquered by force as a privately owned money hub and do not care about the consequences of their irreversible and damaging actions.

While natural and cultural resources are quickly dwindling, Bahrain still has the necessary human and financial capital to map out a more equitable and sustainable trajectory for all its citizens. This is despite the great injustices and suffering many Bahrainis have experienced at the hands of the regime and its security forces. Since the 1920s, Bahrain has witnessed several uprisings demanding civil rights and basic freedoms. As my father warned two decades ago, given the current state of affairs, soon there will be little left to fight for. Yet the Bahraini people have persevered. Bahrain’s Tamarrod [Rebellion] has announced a campaign of widespread protests on 14 August 2013, which marks Bahrain’s independence from British colonization. This is also part and parcel of the ongoing uprising that started on 14 February 2011 to demand the basic right to self-determination. If Bahrainis do not unite against political, cultural, and economic exploitation, what little hope is left for the political, economic, and environmental landscape will soon disappear. All that will remain is the beautiful mirage of my parents’ memories of a Bahrain that once was.

[Image of what Bahrain used to look like. Image by @s_aljaresh.]