Christiane Gruber and Sune Haugbolle, editors, Visual Culture in the Modern Middle East: Rhetoric of the Image. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Jadaliyya (J): What made you put together this collection?

Christiane Gruber and Sune Haugbolle (CG & SH): When we first met at a memory studies workshop in 2007, we talked about the need to bring visual culture as an emergent discipline into communication with media studies of the Middle East. In our discussions, we agreed that it would be fruitful to exchange ideas and materials in a workshop format, so we organized a conference on “Visual Culture in Political Islam,” which was held in Copenhagen in 2009. At first, we were not certain that our call for papers would yield results. However, when we received over ninety paper proposals, we realized that many colleagues in cognate fields were pursuing research on a variety of topics based on visual evidence. This enthusiastic response made it clear to us that there was a strong need to work collaboratively in order to establish a framework of inquiry for the visual presence and production of modern Middle Eastern societies.

This edited volume is a result of the 2009 conference. It took four years to reach publication, and the articles were all written before the Middle East uprisings that began in 2011. Before the uprisings, we each had our feelings about the shortcomings of contemporary media studies. Working on the conference and the book has allowed us to fill in what we perceive as gaps in scholarship, in particular carving out an analytically sound, ethnographically rich, and geographically varied approach to modes of visual expression in Middle Eastern contexts. Our different backgrounds in modern Middle Eastern studies and Islamic visual culture meant that we came to the topic with several sets of theoretical and comparative literatures, and the volume’s contributors greatly enhanced our own fields of expertise and bodies of knowledge.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

CG & SH: The conference was initially framed as addressing “Islamic Visual Culture.” As it turned out, many of the papers did not address specifically Islamic topics, and we felt uncomfortable speaking about visual cultures that were somehow “Islamic.” The appellation “Islamic” struck us as essentialist and flawed. In the end, a major theme in the book addressed the constructed nature and inherent fluidity of Islamic and secular ideologies in public culture. The volume’s title, Visual Culture in the Modern Middle East, aims to reflect our collective refusal to define a set of visual materials as inherently “Islamic.” Instead, we preferred to explore the notions of intersection, combination, manipulation, and negation through a series of tightly focused case studies.

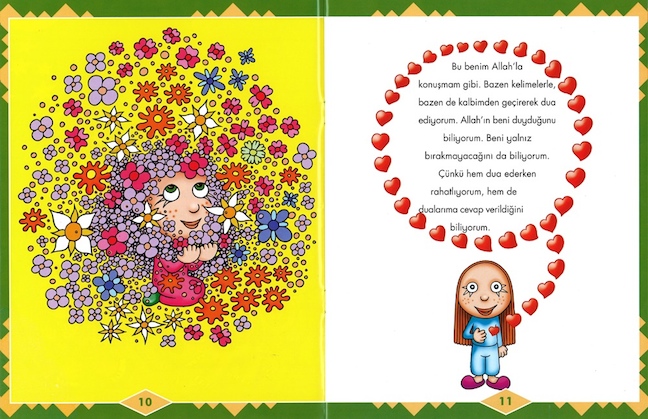

[Dua Etmeyi Biliyorum, written by Çiğdem Özmen, illustrated by Ahmet Keskin, 2008.]

[Ramiz Gökçe (1900–1953), The Turkish Alphabet leaves the Arabic Alphabet in the dust, Cumhuriyet, November 30, 1928, Atatürk Kitaplığı, Istanbul.]

The volume includes chapters on Palestine, Syria, Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Lebanon. The articles are divided into four thematic sections: 1) Moving Images; 2) Islamist Iconographies; 3) Satirical Contestations; and 4) Authenticity and Reality in Trans-National Broadcasting.

The first section tackles the multiple dimensions of “moving” images in order to highlight the fact that the meanings of artworks and visual materials are constructed and pliant; that images, including televisual ones, are not bound or localized but increasingly attain their multiple meanings through globalized aesthetics; and that their adaptations and interpretations are conditioned by culturally encoded modes of viewing.

The second section explores modern iconographies in a variety of Islamicizing contexts. In particular, it investigates how mass mediation has changed the use of visual materials, including those harnessed by Islamist groups. It also explores the overlaps and cross-references between religious and secular ontologies through the deployment of symbols, logos, and pictures.

The third section examines the use of satirical images in modern public culture by focusing on how cartoons and graphic arts can test the limits of accepted narratives on Islam. More specifically, it explores the various degrees of acceptable subversion and the ways in which they clash and compete in an increasingly global and fractious mediascape.

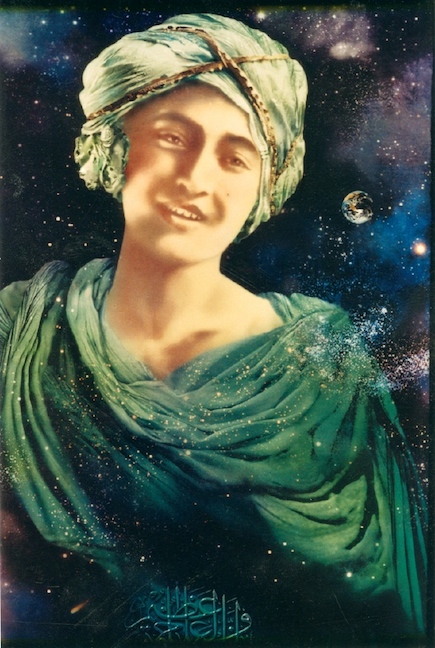

[Left: Murat Süyür (Turkish, born 1984), Darkness, 19 February 2009. Right: Muhammad as a young boy among the stars and planets, postcard purchased in a supermarket, Tehran, Iran, 2004.]

Finally, the last section looks at what visual tools and strategies contribute to the definitions of what is considered authentic and real in mass-mediated and staged representations of Islamic subjectivities in trans-national broadcasting. The papers included in the volume’s section explore the extent to which Islamist ideologies have become dominant in Arab satellite television through drama series and reality programs.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous research?

SH: I have always been curious about the way societies negotiate norms and values through public culture. For a long time, beginning in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the public sphere was the dominant theoretical framework for these debates. I—and I am probably not the only one—have grown wary of the blandness of public sphere theory. It does not capture the emotions and energies, the immediate potential for political transformation, at play in public culture. I think this publication takes important steps towards viewing mass media not just as the realm where collective ideas are negotiated, but also where aesthetic and emotional registers are worked out, and where a politics of everyday life connects individual and collective norms.

[Mural of Muhammad’s ascension, located at the intersection of Modarres and Motahhari Avenues, Tehran, Iran, 2008.]

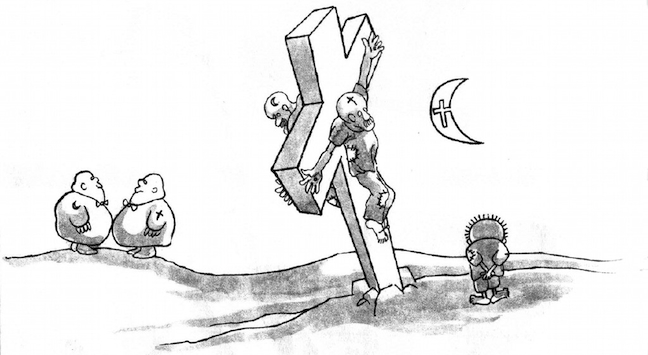

[Poor Christians and Muslims united in suffering during the Lebanese Civil War, while rich Christians and Muslims are united in ignoring them, and Handhala observes. Unpublished drawing, 1978.]

Theoretically, this is a step back in time from liberal public sphere theory to the work of Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, and others who in the 1960s and 1970s, an ideologically charged age not unlike today, thought about the relation between ideology and public culture. Raymond Williams in particular had a lot to say about what we call sensibilities and subjectivities today. Their work needs updating, and new social theory addresses ideology in ways that make sense in our time of uprisings. I really think the moment is right for a return to ideology, both in Middle East studies and in media studies.

In my recent work, and as head of a new research group at Roskilde University called Secular Ideology in the Middle East, I try to pursue this line. I see this book as an attempt to think through not just the role of visual culture, but also the formation of secular and Islamist registers in public culture.

CG: As a historian of Islamic art, my training focused on pre-modern materials, in particular illustrated manuscripts. While researching in the Middle East over the past decade, I became increasingly interested in modern and contemporary practices of image making from Cairo to Istanbul and Tehran. I wanted to find out more about all aspects of visual expression, above and beyond the rarified world of the “fine arts” and art galleries. I am especially interested in the intersections between politics, religion, and the power of visual production in crafting both everyday worlds and ideological programs in public arenas.

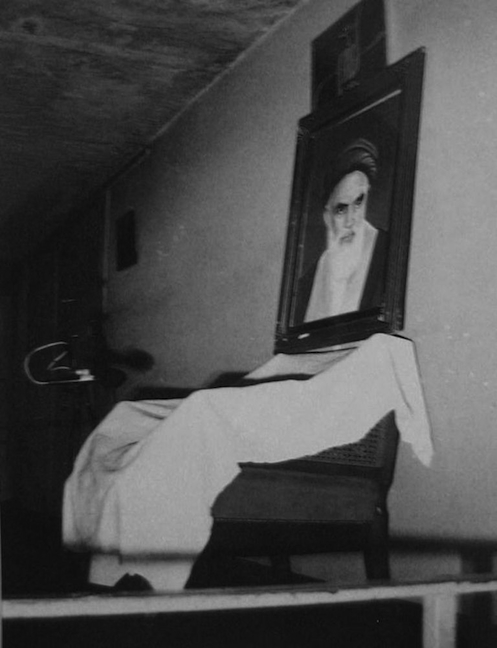

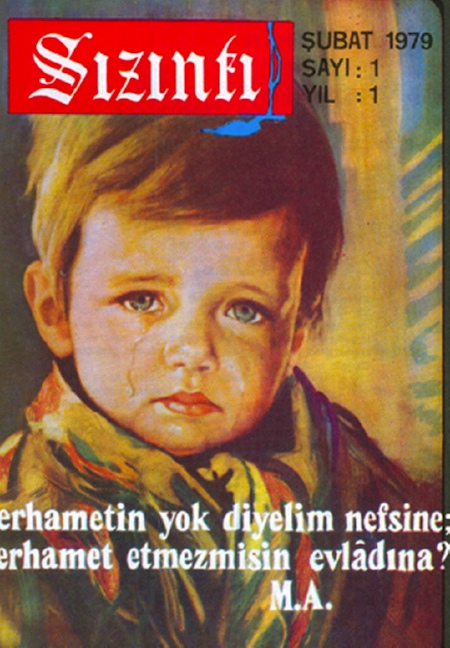

[Left: Khomeini`s chair, Jamaran, Tehran. Image courtesy of the Organization for Cultural Heritage (Miras-e Farhangi), Tehran, Iran.Right: Crying boy on the cover of Sızıntı, February 1979.]

While a number of scholars (such as Wijdan Ali, Lentz Lowry, and others) have written about modern Islamic art, especially painting and sculpture, I wished to further understand how a variety of visual expression and communication function and acquire meaning in everyday settings. This meant that I had to explore new materials and disciplines while simultaneously drawing upon my training in art history, whose tools and methods prove especially useful in understanding contemporary modes of visual expression that purposefully seek to be viewed as “traditional” in their visual language, contents, and ideological position.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

CG & SH: We hope that anyone interested in modern Middle Eastern cultures will find this volume of articles engaging and useful. We see the volume as an invitation into further visual inquiry by scholars wishing to explore the construction of Islamic subjectivities, the politics of power, and the formation of identity and belonging in a variety of cultural contexts. We also hope that readers will enjoy reading a comparative study of the Middle East that actually includes Turkey, Iran, and a number of Arab countries.

[Three of four busts depicting Saddam Hussein with the Dome of the Rock as a helmet, Baghdad, October 20, 2005.]

[Twenty-five-pound Syrian banknote, 1978, first issued 1977.]

J: What other projects are you each working on now?

CG: Currently, I am organizing a symposium and curating an exhibition on “The Arts of the Middle East Uprisings,” which will be held at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor and the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn in fall 2013. My hope is that this project will yield a publication dedicated to the role played by the expressive arts in the recent and ongoing uprisings in the Arab world, in particular in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria, Yemen, and Bahrain. I also am working on the Gezi Resistance in Turkey. A preliminary photo-essay on the visual emergence of the movement appeared on Jadaliyya in early July, and my hope is to begin a book-length project on the topic as soon as I finish writing my book The Praiseworthy One: The Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Texts and Images sometime in early 2014. In general, my plan is to continue to pursue research in both pre-modern Islamic book arts and contemporary visual culture over the coming years.

SH: Right now I am preparing a conference on “Global Secularism,” which will bring together political philosophers with area studies researchers to take stock of current debates about the secular. I am very interested in the permutations of categories like secular, liberal, and Islamist, in the Arab uprisings and on a global level. We obviously need labels, but somehow I think these labels confuse us more than they instruct, and they are always prone to political manipulation. Concerted theoretical, ethnographic, and historical work is the only antidote. I am also editing special issues on Arab leftism and one on bio-icons, the outcome of conferences I have co-organized over the last two years.

[Left: Mural of Hosein Fahmide. Tehran, Enqelab Avenue, old version, 2004.

Right: Mural of Hosein Fahmide. Tehran, Enqelab Avenue, new version, 2009.]

These two projects sum up my research interests at the moment and the project I am pursuing with my colleagues at Secular Ideology in the Middle East. We are interested in what it means to be a secular leftist today, and how the history of secular leftism in the region and in the world impacts the ideological transformations that we are seeing. This interest also takes us into the historiography of communists, socialists, and other assorted leftists in the Middle East. So much of this history just hasn’t been done yet. It is daunting and encouraging. Our main focus is Syria and Lebanon, but the topic obviously crosses borders like nothing else, and it is exciting to see new research fields develop.

J: Could you say a bit about some of the key terms that provide the book with its framework—in particular, how you understand the notion of "visual culture," and how you define the "Middle East" or "Islamic world" as a way of framing your analysis of visual culture?

CG & SH: To our minds, the term "visual culture" describes the mechanisms that produce and recycle visual material in our public cultures. Moreover, since the late 1980s, it has come to designate a new interdisciplinary field of study, departing from the traditional methods of art historical inquiry to incorporate theoretical insights from literature, anthropology, sociology, cultural theory, gender studies, film, and media studies in order to examine a wider range of visual materials. Largely a disciplinary offshoot of cultural studies, which gained prominence in England from the 1950s onward, the more narrowly defined field of visual culture has not been without its problems and critics. Debates continue to unfold, calling into question, for instance, whether visual culture is indeed an academic discipline with specific methodologies and objects of study, or, conversely, an interdisciplinary movement whose course may be more short-lived than expected. Anchored within such discourses, this volume takes the position that visual culture indeed functions as a productive field of inquiry and is most useful as an interface between the many disciplines that treat visuality—largely, though not exclusively—in modern and contemporary cultures.

[Wall with posters of Muqtada Al-Sadr and Imam Husayn. Photograph by Ibrahim Marashi, Basra, Iraq, 2004.]

[Surrealistic Mural. Tehran, Jomhuri Avenue, Courtyard of the Najmiye Hospital, 2008.]

The title of the volume, Visual Culture in the Modern Middle East, signals that we are not willing to confine visual culture in the Middle East to a fruitless search for some vaguely defined culturally "Muslim" mode of visual production and reception. Whether laudable or not, defining the term "Islamic" has been critical in the search for an overarching boundedness of expression across the Muslim world. However, we believe that the search for unity cannot be the research agenda for studying modern visual culture. Rather, we are interested in how the variable image speaks in contexts where Islam is part of the life-worlds that imbue cultural spaces with meaning. However, because viewing and producing images are determined by cultural context, Islamic subjectivities naturally play a large role in Muslim-majority societies with ascendant Islamic movements and new media that generate particular kinds of public spheres, where both secular and religious expression are often mutually constitutive.

Excerpt from Visual Culture in the Modern Middle East: Rhetoric of the Image

From “Toward a New Rhetoric”

Visual culture as lived practice creates subjective positionings through image relations, in which the viewing subject exists in and contributes to a society marked by practices of looking and various visual industries that cater to an ever-expanding viewing public. To better comprehend the study of visual production and reception, along with vision and visuality, visual cultures must be studied in localized contexts rather than through totalizing or universalizing discourses. For these reasons, this volume`s aim consists in situating and studying the image, its multiple functionalities, and its sociocultural dimensions within a variety of modern Middle Eastern contexts.

Pivoting from the center of visual culture is the omnipresent, centrifugal image, embedded in journals and books, projected onto television screens, painted onto canvases and cement walls, and implanted into the nooks and crannies of virtual space. In these many real and virtual zones the image does not merely exist qua image, however. Much more importantly, the image serves as a powerful carrier of meaning as well as a sign that hails viewers by "speaking" to them through the symbolic language of form, a kind of interpellation that in turn requires of them a number of active, interactive, and interpretative acts. In order to understand visual messages, the viewing audience thus must possess a particular kind of literacy acquired through a process of cultural training, itself a form of apprenticeship achieved by the learning and naturalizing of pictorial codes. Within expressive cultures, these processes of learning to see in culturally contingent ways are often entwined with culturally contingent ways of hearing and speaking.

The complementary notion that images speak and viewers retort, thereby engendering a colorful and sometimes volatile enmeshment of discursive dealings, is one that has been explored by Roland Barthes, to whom both the contents and the title of this volume pay tribute. In his "Rhetoric of the Image," Barthes informs us that all systems of ideology are formed through rhetorical tools, and that rhetoric itself is built through a set of connotators. The image—like other modes of expression and representation, linguistic or otherwise—includes a wide array of connotators that certainly can "speak" to us, but whose intelligibility is nonetheless always bound by culturally encoded practices of looking, not to mention spectatorial preparedness and consciousness as well. Thus, in the rebounding to-and-fro between the image and its viewer, a visual manifestation frequently turns into a two-way conversation.

But dialogue can quickly turn to debate, as cultural orders are very rarely uncontested or monologic. Instead, cultural formation and differentiation occur through the coexistence of hegemonic and counter-hegemonic discourses—that Gramscian "moving equilibrium"—to which images contribute but one of many grammatical and sensorial systems of signification that can be variously encoded and decoded. For these reasons, interpretative stances on visual signs exist in multiples, and, as Stuart Hall notes, the interpretation of such signs can either fall within the purview of dominant paradigms or be adaptive or even oppositional in character. At times they can be both simultaneously, complicating facile binaries and stressing the fact that the practice of visual exegesis emerges from complex circuits of creating and receiving visual messages within modern systems of multidirectional communication.

Beyond these two dichotomizing categories, a third possibility can also be proposed: namely, as Pinar Batur and John VanderLippe suggest in their contribution to this volume, that images operate in a tertiary space that is carved out from the divide between the visual construction of a given order and its contestation through counter-images. This third space heralds a "nexus of contention," a term proposed by VanderLippe and Batur to describe an interstitial and tense zone existing between the myth of consensus and its questioning. Certainly, one concern that emerges again and again in the various studies in this volume is that of a split between dominant and subversive narratives, between secular and religious articulations, between Islamic and non-Islamic spheres. While admitting to such divides, and their huge appeal across the world, this volume nevertheless aims to provide a constructive abrogation of simple binaries in order to generate a third space of discourse that engages with both sides of the debate.

In brief, we wish this volume to stress a series of negativities in order to prompt new discussions of visual materials within and beyond the Middle East. Such negativities include, for instance, the image`s heterogeneity, illocality, impurity, and instability; that is, its lack of a fixed and single mode of operation both at an iconographic level and within practices of looking within various scopic regimes. Scholars of visual culture, including Mieke Bal, indeed have argued that the visual is impure and culture is shifting, thereby creating fruitful tensions that are worthy of scholarly analysis. These interstices have been theorized by scholars of globalization, and they also have been the focus of scholars of visual culture, itself a discipline whose object domains have largely been restricted to modern Euro-American realms of cultural production.

Image discourses and debates in cultural practices have emerged and matured in the Middle East during the modern period as well and so today are positively ripe for exploration. By delving into the varied rhetoric of the image within and beyond Muslim contexts, we hope that this volume will contribute to a new rhetoric about the image that moves past culturalistic and historicist frameworks. The studies in this volume initiate such a dialogue by adopting a localized and ethnographic approach and by placing the visual image at center stage. In doing so, they aim to shed new light on how visual systems function as discursive tools, how images serve as vehicles for meaningful exchange, and how practices of looking provide channels for cultural contestations within a complex system of communicative exchanges within and beyond the Middle East.

[Excerpted from Visual Culture in the Modern Middle East: Rhetoric of the Image, edited by Christiane Gruber and Sune Haugbolle, by permission of the editors. © 2013 by Indiana University Press. For more information, or to purchase this book, click here.]