Signs of the Times: The Popular Literature of Tahrir: Protest Signs, Graffiti & Street Art. Curated by Rayya El Zein and Alex Ortiz. Special Issue of Shahadat, April 2011. Full issue available here.

In the heady days that followed the January 25 demonstrations in Egypt, the air seemed to crackle with images from the myriad protests and demonstrations and strikes and uprisings all across the country. For those of us following events from outside, it became part of the daily routine: together with watching the latest reports from al-Jazeera and reading the latest online news, we took in the images being posted (sometimes within minutes of being taken) on Facebook and gathered into albums on Flickr and Y-Frog, not to mention on innumerable other blogs and sites. All this constituted a sort of free-floating archive, albeit one that grew (thrillingly) by the second and thus became harder and harder to negotiate (and this archive, of course, continues to grow as the political struggles in Egypt continue).

One of the great strengths of the current special issue of the online journal Shahadat, published by ArteEast, is that it simultaneously evokes the sense of those days, in all their joy and uncertainty and grief and wonder, while also working to provide an analytic framework for thinking through the remarkable cultural output that arose from, and helped to constitute, the Egyptian Revolution. Signs of the Times manages to create a particular archive that represents several important aspects of the enormous mass of online images from the Revolution, an archive intentionally focused on and limited to a particular place and time — Midan Tahrir between January 25 and February 11, the day of Mubarak’s forced resignation. The issue includes images that have been curated from the online galleries of seven photographers — Kodak Agfa (a name used by Zeinab El-Gindy), Jehan Agha, Sarah Carr, Jano Charbel, Hossam el-Hamalawy, Gilad Lotan, and Ramy Raoof — many of whose Flickr streams and blogs will already be familiar to readers and viewers who follow events in Egypt.

The subtitle of Signs of the Times gives a sense of its multi-dimensional approach: “The Popular Literature of Tahrir: Protest Signs, Graffiti & Street Art.” By considering these signs of the times as both forms of visual culture and as popular literature, the curators of the issue, Rayya El Zein and Alex Ortiz, provide a number of suggestive openings for further cultural and political analysis.

Rather than working chronologically or trying to provide a single overarching framework, the curators arrange the images into seven separate categories. The first, “Mass Production,” focuses on the sheer size of the archive, which relates in turn to the staggering numbers of people gathered in Tahrir, and the equally staggering profusion of signs, graffiti, and art, including words and images displayed directly on the bodies of protesters.

["Free people." Image by Hossam el-Hamalawy. From Signs of the Times.]

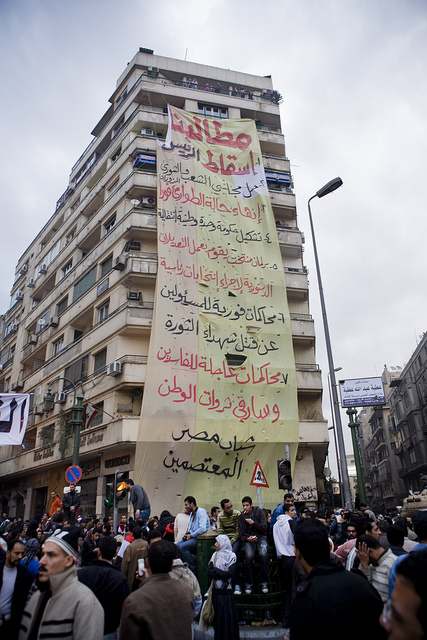

In the section entitled “Changing the Narrative,” El Zein and Ortiz focus on the ways that, as the protests continued and intensified, demonstrators used various means to express the demands of a coalescing movement, whether enumerated in individual signs held by protesters or on the celebrated multi-story banner listing the demands of the April 6 Movement that was suspended from a building.

[Left: "No to state security, emergency law, violence" and "We want dignity, not the sustaining of torture." Image by Ramy Raoof. Right: The demands of the April 6 Youth Movement. Image by Hossam el-Hamalawy. Both from Signs of the Times.]

In “Might of the Mundane,” the curators note the ways that protesters increasingly incorporated humor and forms of visual and verbal creativity which, in their words, “buoyed participants facing the simple act of endurance needed to maintain Tahrir Square.” So the all-present demand “Leave” became, in smaller individual signs: “Leave, I miss my wife”; “Leave, my hand hurts” (or my favorite, which doesn’t make it into this particular archive: a sign with “Leave” written in a form of pseudo-hieroglyphics, with the statement underneath: “So you can understand, O Pharaoh!”). Just as important as this deployment of humor and creativity, El Zein and Ortiz suggest, was the sense in which the sheer fact of endurance, and the need to incorporate elements of everyday life into the protests, led to a larger breaking down of public and private that gave the space of Tahrir its particular quality.

[Image by Hossam el-Hamalawy. From Signs of the Times.]

The section “Words and Images” is where the curators make their strongest case for seeing the signs and graffiti and public art of Tahrir as a form of popular literature — or, as they put it, a kind of “short-form literature.” Their argument here is different from those who, like Elliot Colla, spell out the specifically poetic nature of the protests: not poetry as a metaphor, as Colla puts it, but “the actual poetry that has played a prominent role in the outset of the events,” including the couplets and phrases chanted in the streets and informing the graffiti and signs. El Zein and Ortiz, by contrast, seem more interested in placing the images they present in a larger inter-disciplinary exchange between words and images that they see as a defining aspect of “our contemporary moment.” This is a point that needs to be fleshed out a bit more for my satisfaction, but the images they present in this section are certainly eloquent examples of the powerful conjunction between word and image in Tahrir Square, even in the fleeting forms of graffiti and street art, such as the remarkable cartoon on the side of an abandoned vehicle that includes Mubarak declaring “Oh brothers, hitting with shoes is a sin” and “Goddamn your house to hell, Ahmed Ezz!”; a fortune teller reading Mubarak’s future (“I see a long journey to Germany in your future”); and the Egyptian people declaring to Mubarak: “We’ll do you like Bush!”

[Image by Jano Charbel. From Signs of the Times.]

In “Translating the Revolution,” the curators note the ways in which the protesters imagined themselves, from the beginning of the demonstrations and increasingly so as they continued, as addressing an international audience, as well as their ingenious use, not just of various languages, but also of strategically chosen images, such as re-imaginings of Barack Obama’s iconic campaign poster.

[Image by Gilad Lotan. From Signs of the Times.]

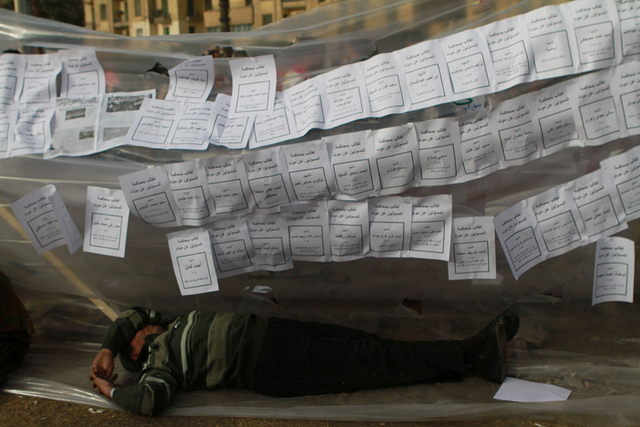

The section on “Productive Memory” provides an especially important context for viewers, especially in light of the remarkable use of humor in many of the images from Tahrir and the general celebratory tone that runs through this archive. Here they remind us of the violence aimed at protesters by state forces, the bravery of protesters in combating this violence and the sacrifices this resistance entailed, and the efforts made, within the continuing demonstrations themselves, to memorialize the martyrs of the ongoing Revolution. Indeed, as they note, insofar as a major inspiration for the January 25 protests was provided by groups mobilized around the murder of Khaled Said by the police in June 2010, this element of mourning and memorializing was a central part of the movement from its inception. Especially striking here is Sarah Carr’s photograph of a protester sleeping under a series of signs with the names of those killed, each one reading: “We demand the prosecution of those responsible for the deaths of these martyrs” (it should be noted that this photograph was taken on February 25, two weeks after Mubarak’s resignation, and thus gestures towards the still-ongoing demand for bringing those responsible to justice).

[Image by Sarah Carr. From Signs of the Times.]

In the final section, “Evolution of a Revolution,” El Zein and Ortiz focus on the future, both in terms of the ongoing political struggles in Egypt since Mubarak’s resignation as well as the “channeling, splintering, and transmogrification of political energy” in the wake of the Egyptian Revolution. Visually, this is one of the weaker sections of the collection; the ongoing influence of the Egyptian Revolution in the region is represented by two photos of graffiti from Libya. But the curators have nevertheless provided an interesting framework for going further with these questions of channeling, changing, and transmogrifying energies, which is an advance on those who speak more simply of a sort of revolutionary “contagion” or some sort of automatic domino effect to explain the ongoing popular uprisings throughout the region. Indeed, they end with what they see as the central question for future analyses: “how the protesters of Egypt’s Revolution came to encourage others, and how that cultural production continues to affect the type of energy seen on the streets of Cairo and around the world.”

In a less explicit but still very real sense, Signs of the Times also presents us with a particular question: to what extent do we now “see” and read the images from Tahrir as refracted through the successful (although still contested) outcome of the Egyptian Revolution? How do we, by contrast, “see’"and read the equally stirring images from, say, Bahrain, of equally brave, creative, resourceful, and resolute protesters, whose popular revolt was nevertheless violently repressed, at least for the moment? What sort of a cultural politics of memory and of the image do we need to evolve in order to do justice to the cultural productions of both the “winners” and the (for the moment at least) victims of the ongoing popular struggles?

[Bahraini protester in Manama. Image by Hasan Jamali.]

There are other questions still remaining to be answered as one reaches the end of Signs of the Times. For example, the characterization of the cultural products that came out of the protests as a form of “popular literature” is very suggestive, especially given the fact that the more “traditional” oppositional intellectual forces from Egyptian cultural life played a largely supporting role (or, in a few shameful cases, an actively reactionary role) in the uprising, but the exact nature of such a popular literature remains unclear. Similarly, the focus on Tahrir, while understandable from the point of view of assembling a visual archive, threatens to further the larger trend towards forgetting the fact that the protests, demonstrations, uprisings, strikes, and other actions that led to Mubarak’s departure occurred throughout the country, and indeed that many of the most decisive actions occurred far from Cairo, in favor of a sort of cultural memory that centers solely around Cairo and, more specifically, around Tahrir.

There is also the question of whether the still image itself is really the most representative form of visual culture with which to think through the cultural politics of the Egyptian Revolution. Certainly the images that the curators include in this issue, like the thousands of other photographs that make up the larger archive from which they drew, circulated widely and helped determine the way people outside Egypt saw and understood the popular uprising. But I would argue that another of the things that helped define the global viewing of the Egyptian Revolution was the almost instantaneous circulation of videos, beginning with the videos circulated by the organizers of the January 25 demonstrations, and continuing and intensifying as the protests themselves intensified. In the past, even after the dawning of the internet, what were often most remembered were iconic images from global events: the lone protester standing before a tank in Tiananmen Square is perhaps the paradigmatic instance. The word “iconic” here is the right one, insofar as such an image comes to stand in for the larger reality being represented. But in the case of the Egyptian Revolution, those outside who were following the events first “saw” many of the images from Egypt not in the form of still photographs, but in the form of video, and not just through media broadcasts but just as often through amateur videos posted online. The famous and much-circulated video (captured by Al-Masry Al-Youm, among others) of protesters magnificently fighting their way through security forces to cross the Qasr al-Nil bridge on the “Day of Anger” on January 29 has become, for many, one of the defining “images” of the Egyptian uprising.

In terms of understanding the mass nature of the protests, and the staggering dynamism of the movement, it may be that no still image can compete with, say, the sense of awe engendered by watching wave upon wave of protesters marching through the streets of Alexandria (even in the face of massive state violence) in amateur video footage captured on February 9.

Furthermore, the capacity of amateur videoists to incorporate montage, music, and other cinematic elements into videos that can be quickly uploaded has made this form of spectatorship central to the experience of the Egyptian Revolution in a way that, I would argue, is quite different from global events of the past. Take, for example, this video montage, labeled by one of its posters on YouTube as “The most AMAZING video on the internet,” first uploaded on January 27 and viewed more than 2 million times.

To their great credit, the curators are aware of all these points. Regarding the question of still images, for example, they write in their conclusion: “while a photograph may capture a moment, political and aesthetic energies don’t stand still.” Indeed, what is most noteworthy about Signs of the Times is that, in an online journal issue of less than 40 pages, they have covered such an impressively large amount of ground. Rather than being paralyzed by the sheer size of the visual archive of the Egyptian Revolution, they have provided their own carefully curated version of a particular slice of that reality. They have also provided an interesting and provocative framework that subsequent viewers and analysts will be able to use, adapt, and contest in productive ways.

Most important, I would suggest, they have eschewed any sort of pretense towards objectivity or scholarly “neutrality,” producing in the process an exemplary form of politically-informed aesthetic criticism of a sort that is badly needed right now. “Critics…will already have noted that in pretending to critically understand the romance with Egypt’s Revolution, this exercise nevertheless recreates it,” the curators write at the end of the issue. I don’t think any such apology is needed. Signs of the Times is a fine example of cultural work that is directly informed by its political desires. This to me is less a romanticization of the Egyptian Revolution than it is an attempt to do justice to the revolutionaries’ own astonishing blend of the political and the aesthetic in the ongoing struggle, a blend that we can observe in the popular uprisings throughout the region that have come to be called “The Arab Spring.”

It’s inevitable, of course, that following upon such a massively significant set of events as those that comprise the ongoing Egyptian Revolution, there will be attempts to contain the meanings of the event within already-existing paradigms of understanding. The mainstream media has certainly done all it can to provide ways for readers and viewers to “understand” these events; the New York Times’ “Reading List for the Egypt Crisis” provides a particularly good (meaning bad) example of such an attempt, bringing the reader back to the familiar discourse of Western “experts” and CIA analysts and focused almost obsessively on political Islamist movements (a fine critique and alternative can be found here).

Against this tendency have been the crucial analyses, many of them produced by those who themselves participated in the demonstrations and protests, that have begun to emerge and become available to English-language readers: Mona El-Ghobashy’s painstaking and astonishing analysis of the praxis of the revolution; Hossam el-Hamalawy’s important refutation of the simplistic understanding of the revolution as “non-violent” and the reminder that it involved the need to actively fight back against and overcome the overwhelming violence deployed by the state; Noha Radwan’s chilling first-hand account of the use of gendered and sexual violence by the state apparatus, a form of state violence that long predated the protests. Signs of the Times is an important contribution to this ongoing intellectual work. Hopefully it will give rise to further conversations and analyses of the sort that could lead to the kind of revolutionary cultural politics necessary to do justice to the revolutions of our contemporary moment.