Eliane Raheb, director. Sleepless Nights [Layali Bala Noom]. Itar Productions, 2012.

Jadaliyya (J): What made you create this film?

Eliane Raheb (ER): The idea of executing the Sleepless Nights documentary came gradually. I first read the apology and the confessions of Assaad Shaftari back in 2002, when a local newspaper published them in a three-part series. He answered several questions I had after the end of the civil war. I read his testimony, but I wanted to know more about him and his experience through the Lebanese civil war, how a normal human being turns to a fighter, a war planner…and then, as soon as peace is announced, he returns to the starting point, a normal citizen. I wanted to know the size of the damage he caused himself and others, and the responsibility he holds. I wanted to know why the war started. Who ruled the “Eastern part” and why we were scared of them? What was the reason for the fear my parents lived? Why? Why? Why? Then the war ended, the peace and silence spread…and the questions remained hanging.

I met Assaad Shaftari back in 2004-2005 in a totally different context from the idea for the film. Back then, he approached the association where I worked, asking for help in producing an educational film that would teach Lebanese youth about all the religions. At that time, I took a chance and told him we would answer his request, but it was obvious that the challenging film would be about him. He didn’t take my words seriously.

The events of 7 May 2008 made me feel an urgent need to proceed with this film. One of the young students who worked with me turned into a fighter overnight. He took up arms and started fighting; his sectarianism motivated his march into battle. The previous question presented itself once again: how can a university student transform into a “monster”?

I called Assaad Shaftari. I started developing the film’s idea with the Palestinian director and producer Nizar Hassan. Nizar and I share an artistic vision. He produced my previous film, This is Lebanon. Afterwards, Nizar wrote the Sleepless Nights scenario and edited the film.

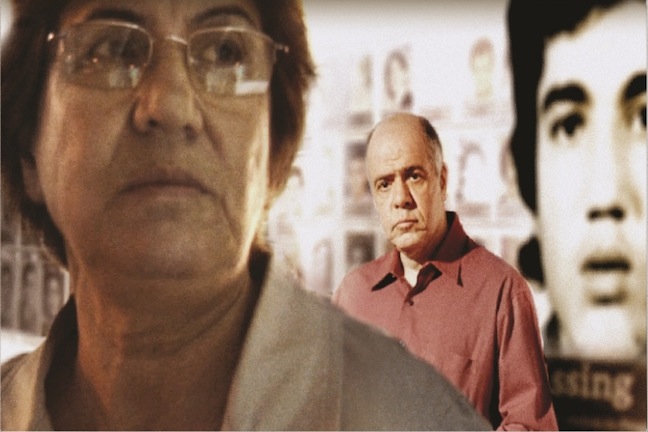

[Still images from Sleepless Nights.]

We started to research the character and his motivations extensively. It led to us to understand Assaad’s own background and role during that time. It helped us analyze where his responsibility lay, and why he made his public apology and confessions. Later on, when I investigated Assaad’s present life, I learned that he is helping some of the parents of the missing persons to reveal the fate of their disappeared children as part of his actions to build civil peace. Among them is Maryam Saiidi, a woman who is still searching for her missing son, Maher. Maher was a fighter for the Communist Party at the Faculty of Sciences battle in the year 1982. It came to my attention that Shaftari passed information to Maryam. Maryam then became a second protagonist in the film. The vision expanded from confronting Assaad with his past alone, to confronting him with Maryam’s story.

Remarkably, Maryam is living her life suspended in the exact moment of the loss—as if the battle happened yesterday. However, she did not surrender and was willing to question anyone who could provide her with information regarding her missing son, and confront anyone who is an obstacle in her quest. Her confrontational and dynamic attitude created a dialectic line to Assaad’s character, and their encounter in the film brought new meanings and explorations of the difficult “truth” and “reconciliation” process in today’s Lebanon.

J: What particular topics and issues does the film address?

ER: In the film, we did not want to present a typical historical work. Instead, we wished to read the past starting from the present, reflecting the effect of the lack of national debate between enemies of the past, and between the people who still carry wounds from the civil war.

We tried to address the fact that the personal story between Assaad and Maryam—and their relationship with the war—represents only a fraction of the other stories about memory, war, self-destruction, loss, and the quest for truth and reconciliation during this period of amnesty.

[Director Eliane Raheb with Maryam Saiidi and Assaad Shaftari. Image via the author.]

The film could be a metaphor for other similar stories, in Lebanon and in the world. It mainly asks: How can human beings create traps for themselves from which it is difficult to be released? How do they find their own ways of salvation when there is no national plan to rid themselves of their wounds? It was built on personal testimony rather than historical documents. This approach allows us to say that the truth is not absolute. The only truth that our film conveys is our own cinematic interpretation of the characters: Shaftari, Maryam, and the other people who move around them.

J: How does this film connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

My previous film, This is Lebanon, is a satire about families and elections in Lebanon, where I also confront my Christian family. I am interested in exploring the political identity of the Christians in Lebanon, and Sleepless Nights has a part that deals with this issue too. Stylistically, This is Lebanon looks more like a classical documentary. In contrast, Sleepless Nights—like fictional films—is composed of strong characters, storyline, suspense, psychological and social layers of story, and a script. Nizar Hassan and I used the elements of feature films and applied them to a documentary story with true characters.

J: Who do you hope will view this film, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

Everybody is invited to watch Sleepless Nights and be a "responsible viewer." We offer the experimental material in the film to provoke the viewer to dive in and take “responsibility”: responsibility for collecting more narratives about this war, and dislodging the general amnesty and resulting culture of impunity in which there has been no prosecution—and arguably little accountability—for acts committed during the war.

Through several screenings, I have gotten the sense that the film stirs a sharp debate between viewers; it opens the unhealed wounds caused by the civil war. Often, the discussion was sentimental, which made sense to me, as we are not used to having a collective debate about the war. One of the positive results of the 13 April viewing, on the anniversary of the start of Civil War, is that the families of missing persons and "The Legal Agenda” used the film as evidence of the existence of two mass cemeteries in the courts. As a result, there are now legal proceedings to dig up those cemeteries.

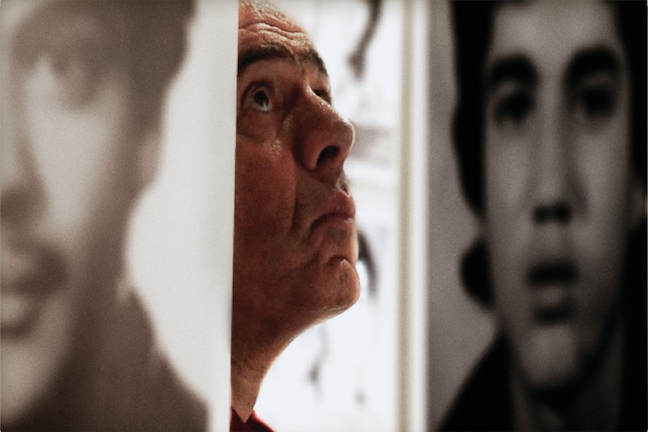

[Still images from Sleepless Nights.]

We also screened the film at the Lebanese University-Faculty of Sciences, where the aforementioned battle took place back in 1982. The students were shocked to discover this history of the very university campus where they study and spend most of their time. A majority of those students were completely ignorant of those events.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

ER: I am not yet done with this film! I guess I need time to rest from this exhausting experience that took four years of my life.

J: What is it like to have the film released at a time in which many fear Lebanon is sliding toward conflict?

ER: I guess since 2005, we have lived in political crisis (this is one of the motives behind the film), and it seems that it is still ongoing. This is why whenever the film is released people will say "why now?" So my answer is "Why not?" Maybe this film can be a mirror for this society in crisis, urging us to look at ourselves clearly and then fully wake up.

J: What are the “truths” reflected in the film?

ER: Through the film “Sleepless Nights,” we offer material with its own internal logic about the truth of our characters and story line. Nevertheless, it remains a collection of personal stories among many more stories that together comprise the civil war. In order for the “Lebanese War Story” to be completed, it should approached by many filmmakers.

Trailer for Sleepless Nights [Layali Bala Noom]