Beirut usually conjures up images of conflict, tension, and warfare. While it is certainly not immune to these dynamics, media reports tend to overemphasize these aspects, just as their obsession with the city’s famous nightlife and glitzy shopping districts pays disproportionate attention to the lifestyles of rich tourists and the elite. This threatens to obscure a day-to-day process that has, in my opinion, a far greater impact on people’s lives and the livability of the city: the continuing large-scale construction boom affecting area after area, tearing down building after building, and replacing them with high-rise structures affordable only to upper middle-class and expatriate Lebanese. Surely, political tensions have abated construction activity somewhat, but after every crisis it has picked up with even more vigor, and indeed many developers used the lull in sales as a speculation tool, buying when the land is cheap and selling when the market picks up again (Ross & Jamil, 2011). Hence, the current slump in investment should not distract from the major changes occurring in the city’s built environment. Indeed, even though the market has currently stagnated, major projects are going ahead as planned.

[Beirut. Image courtesy of Wissarb at the Skyscrapercity forum.]

I will argue that this process is driven largely by a so-called “rent gap” (Smith, 1987), where the low value of existing buildings contrasts sharply with the high value and exploitability of the land, and by large amounts of so-called diaspora capital invested by expatriate Lebanese into the real estate market, with a role for Gulf capital as well. This article will focus on explaining and illustrating these two features and will situate them in the larger framework of the Lebanese political economy.

The AYA-tower in Mar Mikhael

Let us take a look at an example of real estate development in Beirut. The thirty million US dollars AYA-tower, developed by HAR Properties, is located in Mar Mikhael, an area with a distinctly Armenian character that is subject to increasing gentrification, housing an abundance of hip cafes, art galleries and restaurants. One of the founders and major shareholders in HAR Properties is Fahed Hariri, the son of late former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri. Forbes estimated his inherited fortune at 1.4 billion US dollars in 2010. He heads Oger Dubai, established in 2005, an offshoot of his late father’s construction company Saudi Oger, and is head of the latter’s property portfolio and a major shareholder (according to the Zawya database record on the company, retrieved 23 December 2011 from www.zawya.com). Currently living in Dubai, Hariri studied architecture in Paris and says he wants to be an “aware” developer:

In the Arab world, social life is really about public performance. The way you are, the way you dress, the way you walk into a room. Architecture and urban design should enhance the people and that is how you should commercialise space.

Public spaces around buildings are as important as the building itself: “Moments in architectural space and urban living are as important as the absolute notion of shape." He hopes to “participate in the definition of modernity.” As we will see shortly, the promised public space was hardly realized, and the modernity that Hariri wants to help define is mostly reserved for those who can afford to stay in the area.

The neighborhood is marketed as an authentic place, “a haven of peace where life is pleasant and easy”, where you can bump into total strangers “just like on a platform, maybe because the area used to host the former railway station,” where

the Man’kouche salesman from the Nile will become your friend and introduce you to his own fellows, Egyptians just like him. They are the main providers of black gold to all the cars that pass by. Suddenly, you became the next door grocer’s best confident. He’s telling you everything about his sciatica, or about the last twists and plots in his son’s life, and your new friend won’t forget to show you the pictures of his two other kids, that he’s so proud of. Then, you stop by the hairdresser, where you play tawlat zahr (backgammon) with his friends. In the meantime you start to love Turkish coffe [sic] and narguile, and you also understand basics [sic] of Armenian language. At the bend in the path you stop by the EM Chill to have a drink and watch the boiling underground arts scene. … Let’s try this life surroundings full of surprises and oddness (from HAR Properties website, accessed 30 December 2012).

[The Mar Mikhael neighborhood. Image by author.]

The developer bought several lots in September 2009, containing three buildings and a modernist-style abandoned cinema, and merged them in the same month (as evidenced by a Cadastral record obtained by MK on 15 December 2011.) Construction started in Spring 2010 and involved the demolition of the old cinema plus the buildings. According to one of the partners in HAR Properties, the intention was to preserve the existing structures. This is confirmed in an interview with founder Fahed Hariri, where he says he wanted to renovate the cinema into a public performance space with residential units around it. In the end, they decided against it because the cost was too high and the structure would not allow the required twenty-five parking spaces. Financial incentives overtook concerns for public space and heritage. “The old buildings are nice on the picture but not as nice in reality” (interview with HAR Properties representative, December 13 2011). Although the developer proposes a solution to preserve heritage on his own website, the project itself has merely preserved a building façade, and that only because the Minister of Culture ordered them to do so: “The Ministry of Culture asked us to keep these old buildings, we didn’t get anything in exchange but we accepted” (interview, 13 December 2011.) Indeed, in the original renders of the project, no such preservation can be seen.

[Left: the old render for AYA-tower (accessed 13 December 2011), showing no preservation.

Right: the new render with preserved façade. © HAR Properties]

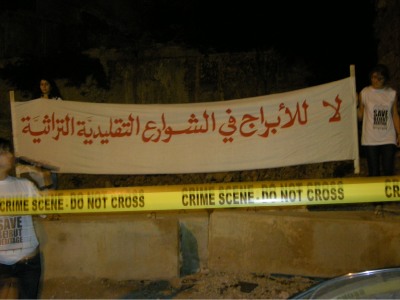

Activists of the local Save Beirut Heritage group have accused Hariri of using political pressure to obtain permits for the demolitions, something that is vehemently denied by HAR Properties. According to one of the main partners in the project, “Hariri is not political, but because of his name you will be criticized.… There is not only Hariri, there are other investors. We are associates in HAR, he is the major shareholder, and I am shareholder” (interview, 13 December 2011). The demolition was not without controversy, and Save Beirut Heritage organized a protest march in May 2011.

HAR Properties decided to “create a thin tall building that cannot be seen from anywhere, it’s where the street turns, so you won’t see it.….The idea was to not have a big impact” (interview, 13 December 2011.)

[In yellow: the lots merged by HAR Properties in order to build AYA Tower. Most structures visible have been demolished, except the façades on the northern side of 633, which were ordered to be preserved and consequently incorporated into the adjusted design. In the satellite picture, dated 23 February 2011, the red roofs of the old buildings to be demolished are still visible, while the cinema has been demolished already. Image composite of Cadastral map and Google Earth photo, by author]

[Protest organized by citizens` group Save Beirut Heritage, May 2011. Image by author.]

According to the record taken from the Land Registry, the buildings on lots 633 and 1159 contained eight shops, a bakery, two mini-markets, and fourteen one-bedroom apartments before their eviction. Eight tenants remained and were paid a total of nine hundred thousands US dollars to leave. HAR Properties says that “[t]he building we bought belongs to eight brothers and sisters, they don’t get the rent, it’s the old system” (interview, 13 December 2011). Ironically, the AYA-project takes part in destroying the marketed authenticity of Mar Mikhael, by evicting the locals that prospective buyers were supposed to interact with. The company’s earlier reference to the “boiling underground arts scene” that future buyers would enjoy watching is another ironic sales pitch, as precisely those “underground” artists and creative entrepreneurs that settled in Mar Mikhael initially are driven out of the area by the increase in real estate prices that projects such as the AYA-tower set in motion.

The project is marketed on HAR Properties’ website as high-quality housing in a once-forgotten neighborhood full of architectural charm and potential. In an interview (published in Ekranua Luxury Real Estate Magazine, 15 September 2010), Vice President Tabet explains: “Our target at Har Properties is towards places that have a future potential to grow. Besides, this kind of regions [sic] would allow us to offer more affordable prices for customers, as prices are not as elevated as other neighborhoods of the capital.” About seventy percent of the planned apartments have been sold at the time of writing. According to HAR Properties, prices start at three thousand US dollars and rise to about 4200 US dollars for higher floors, allowing people to buy a property from half-a-million US dollars to around 1.2 million US dollars (interview, 13 December 2011). This is hardly affordable housing in a country where the minimum wage is set at around five hundred US dollars a month. Facilities include a gym and a swimming pool. The developer is adamant that he does not sell to speculators: clients are “one hundred percentLebanese, but about half of them are living abroad, in Europe, Dubai, Qatar…” The smaller apartments go to people actually living in Lebanon. Arguably, it is hard to see how a developer would identify a speculator, especially since most clients live abroad and might as well have bought the apartment as an investment.

[Demolition of buildings on AYA-site. Images by author, taken in April 2010 and April 2011.]

The AYA-tower is representative of the large-scale ongoing real estate activity in Beirut, the results of which are visible throughout the city: high-rises punctuate the skies at irregular and ever closer intervals, trapping fresh sea winds, collecting dust from construction taking place elsewhere, and adding traffic to a city already bursting at its seams during rush hours. Existing residents are either bribed or bullied into leaving or see their neighborhood change beyond recognition. When evicted, especially if they were on a rent-controlled contract, compensation is rarely sufficient to find alternative, comparable housing. Beirutis looking for a starter home are a victim as well, since new apartments have become unaffordable even to most middle class Lebanese. Increasing numbers of local residents are only able to afford to live in the city with the help of remittances from relatives abroad. Otherwise, they give up on trying to stay in Beirut and move out to its suburbs, which are becoming subject to increasing land prices as well. This process exacerbates the dire traffic situation in the city, which has no efficient public transportation system; most people relying on their private cars therefore find themselves commuting to work for hours every day. Last but not least, the architectural heritage of the city is disappearing at a steady rate [1], [2], [3] with the continuing demolition of older buildings and the inability –and probably unwillingness– of the administration to protect them.

Here we have seen the factors at play in Lebanon’s real estate boom: a large rent gap ensures that the developer can buy the existing buildings from the landlords, who were not getting returns on them, and evict the tenants by paying them higher compensations than they would obtain in court. Existing building codes allow the developer to construct an extremely high building and thus exploit the land intensively. The absence of heritage protection allows for the demolition of the older buildings. The role of Gulf and diaspora capital is evident in the vast expatriate demand–seventy percent of apartments were sold at the time of writing–and in the capital of HAR Properties’ shareholders, based mostly in the Gulf and Europe. The rest of the article will explore these factors in more detail.

The Rent Gap

According to the rent-gap theory (Smith, 1987) value (capital) becomes “trapped” in obsolete buildings occupying land that has a much higher potential value. A building’s value decreases over time while the value of the land increases. There are several reasons for this: increased demands on available housing as a result of city growth and advances in construction technology which make new buildings cheaper and more efficient while rendering older buildings less so, especially in combination with rent controls which keep existing rents low.

In Beirut, the disinvestment and reinvestment dynamic is partly a result of government regulations, including strict rent controls for contracts signed before July 1992 and high exploitation ratios (i.e. how much a developer is allowed to construct on a given piece of land) allocated to land occupied by low-rise buildings. Tenants on rent-controlled contracts can pay as little as one hundred and twenty US dollars a year for an apartment, while a zoning system in place since the 1950s provides the highest exploitation ratios in the central areas of Beirut – precisely the most densely built-up parts of the city, where most of its older buildings are located. The high value of land is another factor: prices have skyrocketed during the past two decades due to high rates of capital investment in the built environment, coupled with a consistent demand. Because of these two factors (existing laws and high land prices), the buildings’ perceived obsoleteness can lead landlords to neglect maintenance, demand increases in rents and do all they can to convince sitting tenants to leave in order to cash in on the value of their land. They are therefore usually more than willing to sell their building to real estate developers, who pay the tenants to leave, tear down the building, and construct a high-rise in its place. The resulting scarcity of available land only serves to strengthen the dynamic, as developers scramble to snatch up the last available patches in coveted neighborhoods such as Hamra and Achrafieh.

The Role of Gulf and Diaspora Capital

As a virtual rentier state with a large role for tertiary services, Lebanon’s economic growth is largely a consequence of foreign capital investment. Most of this is channeled into real estate projects. As a result of immense liquidity in the Gulf States and the huge Lebanese diaspora, there is ample cash looking for a “spatial fix” (a solution to capitalism’s periodic crises of over-accumulation through investment in the built environment and infrastructure, see Harvey 2001). This fix is to be found in the country’s advanced real estate industry and supply of older buildings that are deemed obsolete. After the 11 September 2001 attacks in the United States, Gulf capital was less welcome in the West and thus investments in Lebanon increased. Projects by Gulf developers are usually multi-million-dollar, luxurious large-scale residential and commercial developments clustered mainly, but not exclusively, in Downtown Beirut, an area that was completely redeveloped by private company Solidere after the end of the civil war. A brainchild of late Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri, himself a billionaire who made his fortune in the construction business in Saudi Arabia, Solidere benefited from his contacts to attract investors. The 150 US dollars million DAMAC tower is an example. Built by a developer from Dubai, the tower rises twenty-eight stories high and is currently under construction. Versace provides the towers’ interior design. Apartment prices start at seven hundred thousand US dollars while units in the middle of the tower sell for twelve to twenty thousand US dollars per square meter (comparable to Manhattan). Gulf investments are not limited to Beirut, however, as the new gated village Beit Misk shows, located in Mount Lebanon.

[The interior of an apartment in the DAMAC Tower. © DAMAC Properties (source)]

Lebanese expatriates have traditionally invested large amounts of capital in their home country’s real estate market as well, whether as investors or as buyers, and thus keep fuelling not only the supply-side, but the demand-side of the market too. The current uprising in Syria and related unrest in Lebanon has decreased cash flows from the Gulf and Lebanese expatriates somewhat, but many real estate projects are still due to be completed on schedule.

The Rent Gap and Gulf/Diaspora Capital in Lebanon’s Political Economy

As mentioned earlier, the Lebanese state plays a role in the rent gap and the large amount of foreign capital invested in the country. Besides the previously mentioned rent controls, zoning system and the absence of any real protection for built heritage, the state has consistently stepped in to facilitate investors. The Lebanese investment climate has always been friendly, but a program of neoliberal restructuring after the end of the civil war in 1990 saw the introduction of reforms in tax, construction and building laws that facilitated foreign acquisition of properties and land (Krijnen & Fawaz, 2010). A new Building Law in 2004 significantly increased existing exploitation ratios and height limits. This is not surprising, as Lebanese politicians have always had an interest in real estate, often being developers and investors themselves. Besides Rafiq Hariri, the most famous example of a politician involved in real estate is former Minister Michel el-Murr, whose large-scale residential project Cap-sur-Ville situated just outside Beirut violated building regulations. According to several interviews conducted with real estate developers and agents, he used his position as minister to temporarily suspend the law and obtain his construction permit. Less outrageous, but much more embedded in daily business, are the shares of politicians in several real estate development companies and banks. Lebanese lawmakers and politicians, in short, cannot be viewed as separate from vested interests in real estate development.

Conclusion

I have hoped to show that current real estate activity in Beirut can be explained by a large rent-gap due to low returns from older buildings and a very high potential exploitability of land, combined with large amounts of foreign capital pouring into Lebanon via Gulf investors and Lebanese expatriates. Both processes are facilitated by the Lebanese state, whose lawmakers and politicians have vested interests in the booming real estate market. Consequences for the city’s residents are dire. While HAR Properties portrayed the AYA-tower as relatively affordable housing that attempts to bring a notion of public space and uses the area’s supposed charm and authenticity as a sales mechanism, in fact it is part of the profound transformation Beirut has been undergoing since the last two decades that is doing everything to ensure that public space and affordable housing are the last things people can find in the city.

[The author would like to thank Hiba Bou Akar for insightful comments and Eric Verdeil for useful feedback on this article]

References

Harvey, D. Spaces of Capital: Towards a Critical Geography. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2001.

Krijnen, M., & Fawaz, M. “Exception as the Rule: High-End Developments in Neoliberal Beirut.” Built Environment 36(2) (2010), 245–259.

Ross, R., & Jamil, L. “Waiting for War (and Other Strategies to Gentrification): The Case of Ras Beirut.” Human Geography 4(3) (2011), 14–32.

Smith, N. “Gentrification and the Rent Gap.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 77(3) (1987), 462–465.

![[Left: the old render for AYA-tower (accessed December 13, 2011), showing no preservation. Right: the new render with preserved façade. © HAR Properties]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Krijnen_figure3-300x400.jpg)