Budrus. Directed by Julia Bacha. 2009.

Budrus, an award-winning film directed by Julia Bacha and produced by Ronit Avni, documents the struggle of a small West Bank Palestinian village of the same name to prevent Israeli security forces from building the separation wall through its property. Through its struggle, Budrus achieved notoriety as a successful protest movement based almost entirely on non-violence by Palestinians, as well as an early example of cooperation between Palestinian and Israeli anti-occupation activists. The film is a remarkable document of the ongoing struggle for Palestinian rights in the West Bank and succeeds in bringing the audience directly into the middle of demonstrations and clashes, allowing viewers to witness the beatings, tear gas, rubber bullets, and live ammunition used by Israeli security forces. Similarly, comments by Palestinians, Israeli soldiers and border police, Israeli activists, and others are valuable in presenting varying and conflicting perspectives on the events in the village. Nonetheless, Budrus is less successful in providing a historical context of the struggle, and for this reason misses an opportunity to more fully explain the nature of the occupation and accompanying dispossession as well as the Palestinian resistance to it.

The documentary begins in 2003 as Israeli military authorities distribute notices to the locals that describe the path of the wall through the middle of the village’s land, including the village cemetery, and running within meters of a village school. Ayed Morrar, long-time Fatah activist and main protagonist in the film, calls a meeting to argue that resistance is a realistic choice for the people of Budrus. The very next day, a large number of villagers go out to the demolition/construction site to demonstrate against the soldiers and the bulldozers. On this day, the Israeli occupation forces are set back on their heels by the popular resistance. The next day, however, they return and destroy some eighty olive trees. This dynamic of action and response, which continued in Budrus for a full ten months, provides the narrative backbone for much of the documentary. As the film continues, it chronicles many of the twists and turns of the conflict over the village’s land while touching on a number of themes and weaving in commentary by protagonists on both sides.

One of the themes that has been highlighted in some of the previews as well as commentaries on the film is the role of women in the protests. Fairly early on in the struggle, Morrar’s daughter Iltezam appeals to him to let women join the demonstrations. He agrees, and from then on Palestinian women are directly involved in every march. The filmmakers have captured some striking footage of women in action. On one occasion, Iltezam climbs into a hole close to the blade of an excavator to prevent further digging and is followed by several other women. On another occasion, women are filmed blocking a military jeep and then pushing against it when the driver guns the motor. At the beginning, it appears that Israeli soldiers and border police are reluctant to use beatings and tear gas on them, but that soon changes, as the film shows several incidents when women were beaten and tear-gassed along with the men.

It is a credit to the film that it tells the story of the role played by the women of Budrus in the demonstrations, but it leaves the viewer with the impression that the participation of women in Budrus was something unique. Although this might have been accurate for the village itself, it is far from true elsewhere in Palestine, where women have often and for a long time been involved in protests as well as other political activities. Given Western conceptions of Muslim and Arab women, a viewer with limited knowledge of Palestine is likely come away from the film marveling at how bold the women of Budrus were. Unfortunately, the film does not give its audience the context to come to a more nuanced conclusion by saying something about the political action of Palestinian women historically. Yes, the women of Budrus played important roles in the protests, but these roles are more accurately characterized as fitting into the continuity of Palestinian experience instead of marking a departure from it.

Another prominent theme is the role of Israeli anti-occupation activists. At one point in the struggle, Morrar invites interested Israelis to participate, and their presence puts the Israeli army in an awkward position. As Doron Spielman, the army’s public affairs officer in the area, states, “we could not harm them because they were Israelis.” The viewer sees this several times in the film, as soldiers are commanded only to shoot tear gas where there are no Israelis, or not to harm Israelis. Israeli activists are often threatened with arrest, however. Here again, the film shines in showing its subjects in action during protests and in meetings with Palestinian activists. It does not, however, delve into issues surrounding Morrar’s decision to invite them. We do not hear if there was a debate among Palestinians in Budrus about the advisability of having Israelis join their demonstrations, which would have been normal given that, at the time of Budrus, only a couple of years had passed since the outbreak of the second intifada and the harsh repression that accompanied Israel’s reoccupation of major West Bank cities.

Nonetheless, once Israeli activists started to participate in the protests, facing Israeli soldiers and border police, tear gas, and possible arrest, there seems to be a fairly strong consensus among the Palestinians that this was far and away a positive development. Ahmad Awwas, the senior Hamas leader in Budrus, thanked the Israelis publicly for “standing with us…as we defended our land.” In an interview with the filmmakers, Awwas remarked how surprising it was to see Israeli Jews standing with them in opposition to the Israeli occupation.

Towards the end of the film, the confrontation enters a new phase. Israeli security officials tell the Palestinians that they are no longer going to allow the demonstrations to impede the construction of the wall and will take tougher measures if resistance continues. This is exactly what happens. Israeli soldiers and border police occupy the village and impose a curfew, which is resisted by youths throwing stones. Israeli forces fire tear gas and rubber bullets as well as a large amount of live ammunition, to suppress the stone throwers. Demonstrations in the following days are suppressed more harshly than before. In one clash caught on film, security forces beat many Palestinians and shoot and seriously injure at least one person.

At the end, the film’s narration informs the viewer that after several months of protests, Israeli authorities decided to move the path of the wall to the west so it would not encroach on the village’s land. It is a rare victory for Palestinians in their struggle to keep their land. The viewer does not hear, however, what happened in the intervening months.

Non-violence and Successful Protest

At the very beginning of the film, Morrar — speaking in Hebrew — says that the villagers “don’t have time for war and want to raise their children in peace and hope.” Their strategy to bring this about is to use non-violent popular resistance. This statement is an appeal to Israel to “give us hope that we can achieve peace this way.” This view is echoed by Ahmad Awwas, the Hamas leader, later in the film, who states that peaceful resistance has been beneficial, in part because it has given Palestinians international support and in part because if the Palestinians were to use violence, the Israeli army “would use all of their weapons as if they were fighting an army.” As in other historical cases, the decision to use non-violence was calculated and strategic, although there was a moral dimension as well. In his appeal to Israelis to give the Palestinians hope so they could “achieve peace this way,” Ayed Morrar is expressing a preference for peaceful means over violence as well as his hope that Israelis and Palestinians could find a way to live together in peace.

The case of Budrus has been celebrated, especially in the West, because of the villagers’ employment of non-violent protests and other actions. The film shows both men and women obstructing bulldozers and army vehicles, resisting arrest, and tearing down a section of fence. Expressing this view on non-violence, Washington Post columnist Richard Cohen writes: “Those of us who have watched Israel trying to control the West Bank have always wondered why the Palestinians have not tried passive resistance.”

This view, unfortunately, is completely divorced from the reality of a four-decade-long coercive occupation of the West Bank, during which Palestinians have often used what Cohen calls “passive resistance.” In the first intifada, marches and strikes were met by beatings and bone breakings along with tear gas, rubber bullets, and live fire, as well as curfews, long-term school and university closures, and any number of other repressive responses. Israeli occupation forces killed hundreds of Palestinians and severely injured thousands. We see much of the same happening now in other West Bank villages in response to Palestinian non-violence, because this non-violence is a threat to the occupation. It divides Israelis, puts the Palestinians in a good light internationally, and undermines the claim that Israel has no partners for peace.

In the end, the film does not explain or show how the protests in Budrus led the Israeli government to alter the path of the wall. What seems clear is that the continuing protests forced the Israeli military to reassess the situation. Ayed Morrar referred to a “battle of wills” for the ten months of the protests. Faced with the total commitment of the village, along with Israeli and international activist support, the occupation forces apparently decided it would be easier to reroute the wall than to continue the confrontation.

In a clear attempt to downplay the Budrus success, Spielman, the Israeli military spokesperson, claimed that the decision to re-route the wall was a “legal, political decision taken by the Israeli government,” implying that the Palestinian protests had nothing to do with it. Israeli activist Kobi Snitz, on the other hand, more realistically pointed out that the continuing protests actually created a different political reality that the Israeli military had to respond to. The steadfastness of the Palestinians was recognized by Yasmine Levy, an Israeli border policewoman, who credited the Budrus women with a willingness to do anything to protect their land, whether it was being shot with rubber bullets, getting beaten, or being tear-gassed.

The Larger Picture

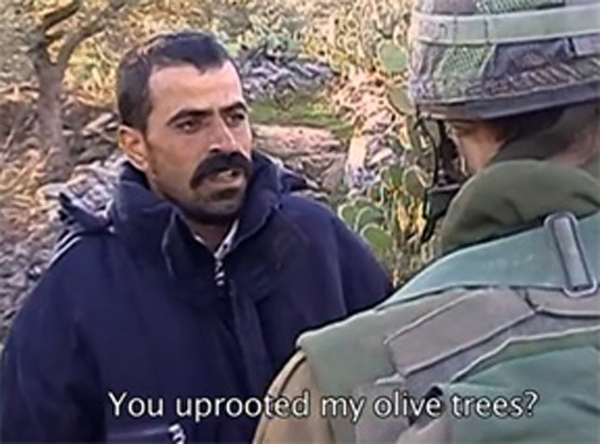

Beyond its on-the-ground coverage of demonstrations and clashes, Budrus gives the viewer insights into what life is like in a small Palestinian village. The audience sees people going about their daily activities, whether it be caring for children or tending their fields. As in small farming communities everywhere, the importance of the land and its fruits is paramount. In this village, like many other Palestinian villages, livelihoods depend on olive trees and other crops, even to the extent, Morrar relates, that the people give the trees the names of their mothers. The shock and pain expressed on the face of one farmer when sixty of his trees were uprooted is intense; it is as if he had lost a son or daughter.

[Palestinian farmer in shock after losing several dozen olive trees to Israeli bulldozers. Still image from Budrus.]

Even though the Israeli security forces understand — in a detached analytical way — the importance of the land for the Palestinians, it does not affect their decisions. Levy recognizes that for the Palestinians “the land was their life” and Spielman admits that the wall is “very unfortunate for the Palestinians.” But it is symptomatic of the great inequality in power and Israel’s obsession with its security that Palestinian needs receive short shrift and Palestinian rights in their own land are essentially non-existent. Security forces break up peaceful marches and demonstrations with clubs and tear gas on the justification, freely given by Spielman, that his primary concern is that Israeli families “sleep at night.” This is a telling comment. Spielman essentially concedes, apparently unwittingly, that occupation means the denial of Palestinian rights, which, together with the continuing dispossession, creates conditions that cannot but drive people to resist.

For Western audiences, who overwhelmingly hear only the “Israel has a right to be secure” narrative, to see the reality and consequences of this drastic imbalance of power between occupied and occupier is perhaps the chief value of the film. The confiscation of land faced by the villagers is an ongoing reality for a large number of Palestinian villages and towns, although it is also the case that issues surrounding the dispossession of land — and the accompanying repression — are significantly more acute in other areas of the West Bank where village land is seized for settlement building and road construction for Israeli settlers.

Budrus provides important insights into the ongoing Palestinian struggle to save their land from Israeli encroachment. But it fails to fully explain why Budrus succeeded. There is a significant temporal gap between the effective end of the film’s coverage of the protests and the actual decision of the Israeli government to move the path of the wall. We don’t know what happened in those intervening months. How many people were arrested? (Early on in the film, we are told that Ayed Morrar was arrested near the beginning of the protests, but we don’t get a sense of how that may have affected matters or how long he was held.) What sorts of actions were undertaken by the Palestinians after the main narrative of the film stops? During the clashes between Palestinian youths throwing stones and Israeli troops using live bullets and tear gas, Morrar is heard telling them — without success — to stop throwing stones. It is clear that at this point, he has lost control over Palestinian action. How long did this situation last? Perhaps it was this more violent action by the Palestinians that forced the Israelis to reconsider. Perhaps the Israelis decided that after the reinvasion of Palestinian cities, it was easier to move the wall instead of continuing the clashes, which had the potential to spread. The film does not say.

In addition to this lapse in the narrative, which potentially weakens the claim about the effectiveness of non-violence, Budrus fails to provide a historical and political context for a discussion of Palestinian non-violence. At the very end, the filmmakers opine that “Budrus has inspired villages across the West Bank to adopt non-violent resistance to save their lands.” No doubt, Budrus did inspire other villages, and at the end we see Ayed Morrar preparing to go to Ni’ilin with some Israeli activists for a demonstration. But the implication is that non-violence is something new and created in Budrus. As stated above, non-violence is a well-known and often-used tactic in Palestine. Budrus did not teach anyone about it. It did, however, provide a model of an apparently successful resistance to the occupation in solidarity with Israeli and international activists that inspired other villages in the bleak days after the harsh military suppression of the second intifada. That model, however, drew from the already-existing Palestinian repertoire of demonstrations and other non-violent methods.

Budrus and Popular Protests in the West Bank

Beyond the revitalization of broad-based protests using non-violent methods — which had mostly disappeared after the first several weeks of the second intifada — the support of internationals and, especially, Israeli activists, was significant in that it marked the beginning of a new phase in the anti-occupation struggle. Since Israeli soldiers were faced with the difficult challenge of having to face fellow Israelis demonstrating with Palestinians — sometimes protecting Palestinians, and sometimes being protected by Palestinians from arrest — they were often unable to act forcefully. In addition, and perhaps even more important, the presence of Israelis alongside Palestinians as witnesses made it more difficult for the Israeli army to brutally suppress the demonstrations.

After Budrus, Israeli activists, such as the group Anarchists Against the Wall, have participated regularly in demonstrations in several Palestinian villages facing circumstances similar to those of Budrus. These joint actions, in turn, have revitalized an activist, anti-occupation Israeli left and started to create bonds of solidarity across the Israel-Palestine divide, as described in a recent article by Joseph Dana and Noam Sheizaf in The Nation.

Another key point that the film succeeds in making about the Budrus case is that there was complete unity among Palestinian factions. The audience sees clips from a village demonstration jointly held by Fatah, Hamas, and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. This unity of purpose and action was seen by all sides as a key to being able to sustain the protests. In his interview on camera, Ahmad Awwas, the Hamas leader, conveyed a deep sense of satisfaction over the coordination they achieved and said they hoped to spread that unity all over Palestine.

Despite the fact that the Budrus example has inspired protests in other Palestinian villages, the chances of success — in the short-term at least — appear to be minimal. Weekly marches and frequent clashes have been taking place for several years now in villages such as Bi’ilin, Nabi Saleh, and Ni’ilin. Israeli repression in these villages has been much greater than in Budrus, with a significant loss of life. In addition, Israeli occupation forces have raided villages — often in the middle of the night — to arrest protest leaders and sometimes their children in order to exert pressure on them and to force the end of the demonstrations. It is quite apparent that from the point of view of Israel’s security establishment and political elite, these non-violent protests, backed and witnessed by Israeli and international activists, constitute a significant challenge to the occupation regime’s absolute control. Therefore, given the harsh repression meted out to the Palestinians, it is abundantly clear that the occupiers have decided that there will be “no more Budruses.” As Ayed Morrar wrote in a recent article: “Israel is sending a clear message — even unarmed resistance by ordinary civilians demanding basic rights will be crushed.”

Nonetheless, it is evident that the combination of broad-based demonstrations employing non-violent tactics, combined with the global campaign of boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) — not mentioned in the film — constitute the Palestinian people’s most effective strategy for building international support against the occupation. Non-violence by itself cannot end the Israeli occupation. But the use of non-violent tactics makes it difficult for the Israeli occupation forces to escalate the confrontation to the point where they can then use maximum force to completely suppress Palestinian anti-occupation actions, as they did during the second intifada. By not responding in kind to Israeli violence, Palestinians have found a way to sustain their protests for an extended period, and in so doing lay the foundation for more widespread actions such as those that have occurred throughout the Arab world in the past few months. Were this to occur in Palestine, it would pose a significant challenge to the Israeli occupation.

Budrus is available from the Arab Film Distribution website.

![[Image from the poster for the film \"Budrus\"]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/budrus.jpg)