Route 181: Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel. Directed by Michel Khleifi & Eyal Sivan. Belgium/France/Germany/UK, 2003

Today Palestinians commemorate the nakba, or day of catastrophe. At the same time, the state of Israel seeks to criminalize this expression of an autonomous Palestinian national consciousness, which threatens to fragment and disrupt Israel’s historical self-narrative. This year, the nakba finds itself in the shadow cast by the Israeli Knesset law, approved on 23 March 2011, which denies state funding to any organization that “undermines the foundations of the state and contradicts its values.” The new law, referred to in popular discourse as the “Nakba Law,” is aimed at dissociating Israel’s Independence Day from the Palestinian day of mourning. In the discourse of both politics and cinema, this day that is forever inscribed with the trauma of past, present, and future begs for recognition. It seems appropriate, then, on the occasion of this year’s nakba, to revisit Route 181: Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel, a film that faced significant roadblocks to its release and one that deserves an important place in Jadaliyya’s ongoing “Essential Viewing” series.

Palestinian filmmaker Michel Khleifi (Wedding in Galilee, Zindeeq) and Israeli filmmaker Eyal Sivan (The Specialist, Citizens K.) began conceptualizing Route 181 in 2001 – before September 11 – shot the film in the summer of 2002 and released it a year later. The film oscillates between a road trip movie and a documentary that traces the route of the 1947 UN Partition Plan, which would have separated Palestine into two states: one Jewish, one Arab. During the shooting and release of Route 181, the idea of a so-called two-state solution was particularly prominent in American discourse, given George W. Bush’s “Roadmap for Peace,” which called for an independent Palestinian state. As it navigates the spaces marked by these historical events, the film is acutely aware of the ways in which both 1947 and 2002 are woven into its texture.

Looking back at Route 181 today, our reception of the film is haunted by the parallel nature of the invisibility of the life that once flourished in the now disappeared Palestinian villages and the difficulty of publicly naming the nakba. The state of Israel is invested in constructing a national vision that is premised on ignoring what it has erased from the territory of Palestine-Israel. The now illegal status of the nakba removes funding for any state organization (including schools, community arts organizations, research institutes, etc) that dares to represent the day of catastrophe. Israeli state discourse reconstitutes mourning the loss of Palestine as tantamount to denying Israel’s right to existence, thereby making it a crime against the state. Embedded in the commemoration of the nakba is the acknowledgement that moral and legal justice is owed to Palestinians. By asserting itself as a historical truth, the nakba unequivocally demands the Palestinian right of return. It also holds a mirror to the system of ethnic segregation and economic domination under which Palestinians have paid for Israel’s national vision. In this climate of contested and competing visions of history, Route 181 returns to our screens newly relevant to the events of not just 1947 and 2002, but 2011.

Cinematic Vision

The film is split into three parts: South, Center, and North. As Khleifi and Sivan travel from Gaza toward the border with Lebanon, the film foregrounds the many disappeared Palestinian villages that have been replaced by Israeli communities. In the way that it deals with the act of filmmaking, Route 181 lies somewhere between cinéma vérité and a reflexive mode of documentary. Khleifi and Sivan conduct a number of interviews with Palestinians and Israelis from all walks of life, while also allowing the camera to observe developments that occur during their journey. In their interactions with their subjects, the presence of the filmmakers is most often felt when individuals display ire or are provoked by the presence of the camera, an apparatus whose legacy in Palestine-Israel is all too familiar, too troubled. Khleifi and Sivan respect their viewers enough, however, to acknowledge the very specific ways in which the cinema articulates its mode of expression. The filmmakers draw constant attention to the film’s enunciation – how it speaks about itself. For instance, they are often present via the inclusion of a sliver of the car door frame, in the left or right corner of the shot, captured as the camera attempts to move across the area of the windshield.

We see iterations of this reflexivity at many levels, but it is most legible in the leitmotif of the journey. The road from south to north is experienced and filmed from the point of view of the filmmakers in their car. Near the end of each section, as the car pulls away and heads to the highway, the camera, positioned in the passenger seat, pans slightly to the right in order to capture both the road ahead, through the windshield, and what has been left behind, in the side-view mirror. The camera then pans left to the center of the car, in order to include another look to the future (windshield) and the past (rearview mirror). Here, Khleifi and Sivan acknowledge the cinema’s educational role: it teaches all of its participants (creators, subjects, spectators) that the only way to barrel through the journey is to gaze constantly at the history of the route.

[From the title sequence of Route 181]

The magisterial title sequence of Route 181 functions as a microcosm of the film’s central concerns. At this early stage, the film takes great care to code its namesake, UN Proposition 181, onto the entire filmic project, suggesting that this early two-state vision and its refutation and failure has literally painted the landscape of the debate.

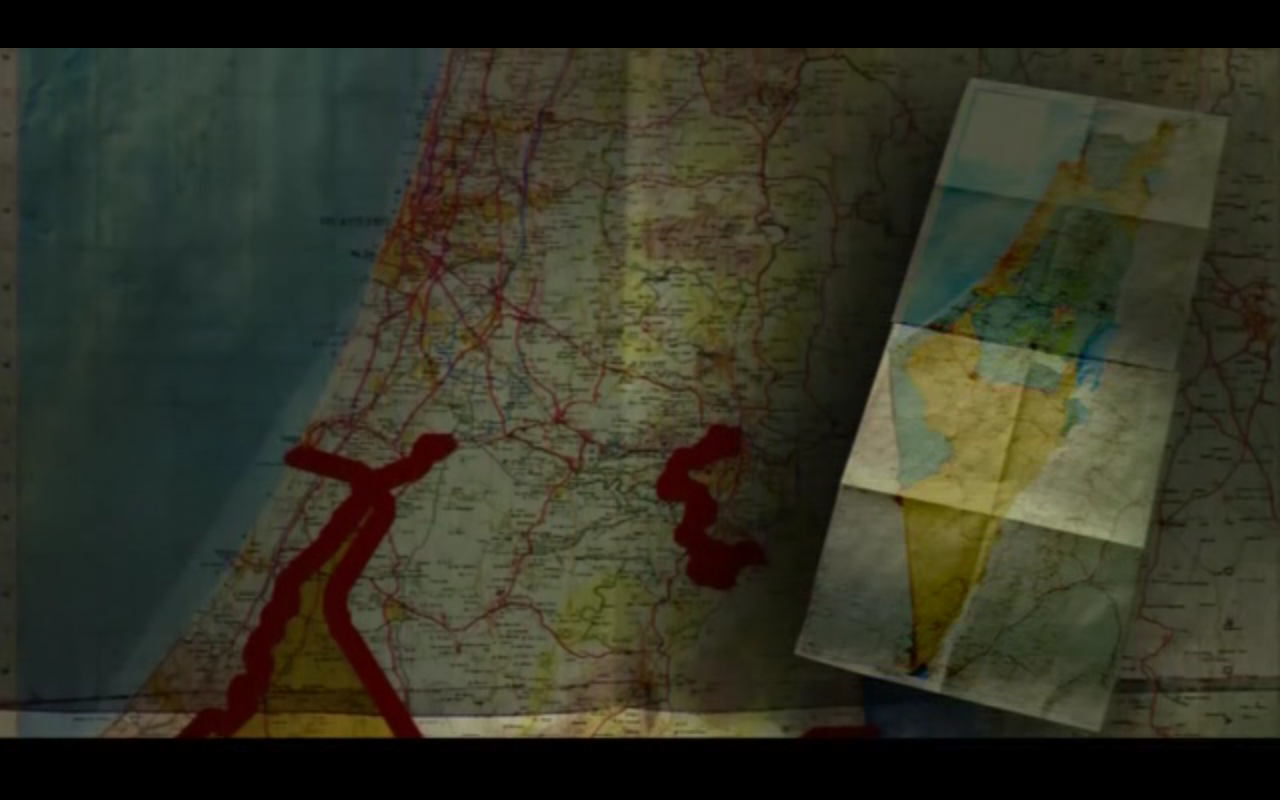

The sequence begins with a rapid montage consisting of three shots of the filmmakers, who are sitting on a bench with their backs to the camera, overlooking a landscape. The next shot marks the time with yellow graphics that read “Summer 2002” in both Arabic and Hebrew, imposed on the same golden landscape. As red graphics in Arabic and Hebrew roll above the date and narrate the conditions of the film’s production, the landscape slowly dissolves onto a shot of a map unrolling in two directions. Already, we are informed of the documentary’s status as a political art project. The filmmakers make no claim to mimesis, per se, but strive to reveal the machinations beneath constructing various truths about the history of Palestine alongside the proliferation of the Israeli national project.

A pair of hands then enters the shot to accelerate the unrolling, now situating the map as an object held by a human. Before we can get too accustomed to this, the directors bring us back to an extreme close up of the map. The unscrolling of the two maps ends with a shot that features a hard object tearing a hole into the map and opening a space into the “real” world of the film. We are reminded of something that is easy to forget in the act of spectatorship/citizenship: the filmic world is this portal, and every vantage point in the “real” world is similarly only experienced via a portal, or fragment. Route 181 insists that vision is always compromised.

[From the title sequence of Route 181]

Khleifi and Sivan’s film is less interesting in the way that it manages to fully represent a spectrum of views held by both Palestinians and Israelis than in the way it comments on its own abilities as a filmic text. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the title sequence, which offers the viewer a nuanced understanding of the dubious portals through which the journey – and the situation – can be understood. The many different understandings of the “fragment” are employed here. We only see slivers of the topographic-cum-road map, its interaction with the human, its transition into a political map and its position on the dashboard. The map guides the journey, while also troubling it through palimpsestic warnings.

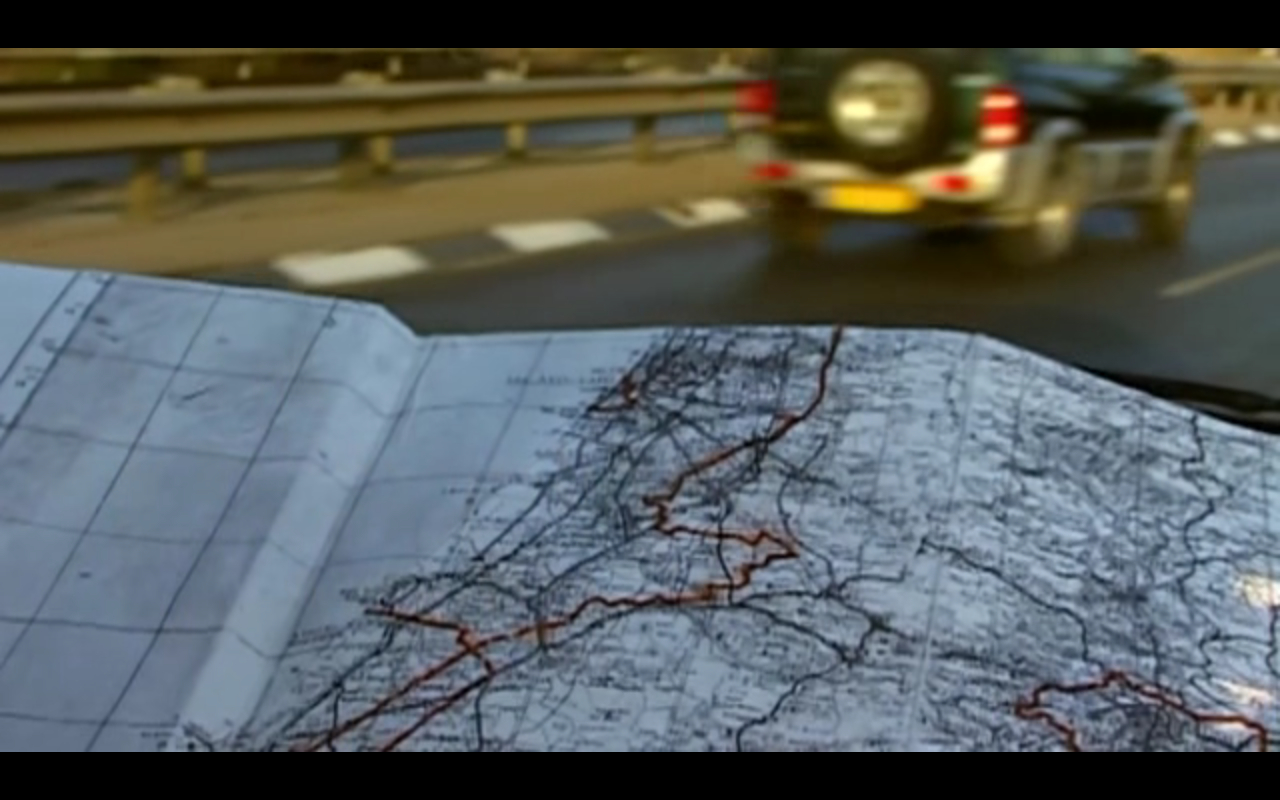

True to its hybrid form of both documentary and road movie, Route 181 employs the motif of mapping beyond the title sequence of the film. As the car belonging to the filmmakers travels down a highway or along a dirt path searching for a “lost” village, the viewer is constantly reminded that the directors’ point of view is painted by the cartographic legacy of the Zionist colonial project. The camera offers a medium shot of the approaching landscape while a folded map of Palestine-Israel lies on the dashboard in the bottom of the frame. The map comes before the physical territory; everything we see in the dirt, rubble and beauty before us is figured – and perhaps overdetermined – by the map, which is reflected in the windshield, thereby leaving its own trace on the world outside the car.

[From the title sequence of Route 181]

[From the title sequence of Route 181]

Living Together

What does “living together” mean? This is the one of the central questions provoked by the film and voiced by one of the interviewed Israelis. In interviews, the subjects reflect on both “living” and “together.” The film asks about the condition of life in contemporary Palestine-Israel and the realities of that thing called “community.”

It is striking that many of the older Palestinians interviewed in the film recall a harmonious time of “living together.” In one such moment, an older Palestinian woman living in Masmiye, in a house that has been in her family for “80-90 years,” remembers that “life was beautiful” when Arabs and Jews (Ashkenazi, Moroccan, Yemeni) lived together. The loss of an actually lived and livable “multi-cultural” reality is thus also mourned on the day of catastrophe. By commanding Palestinians to abstain from this memory, the regime secures its own position as the enabler of community, development, and industry. In short, by attempting to erase the memory of Palestine’s harmonious past, Israel congeals for its citizens the notion that it is the first nation on this territory. Many Israeli Jews interviewed in Route 181 reiterate this national vision.

In the “South” section, the filmmakers (in this case Sivan, since the following interview is conducted in Hebrew) enter a café called “Varda,” which advertises itself as kosher and offers special rates for soldiers. From her position behind the counter, Varda – the proprietor – gazes at a wall she has adorned with framed photographs of Israeli fighter jets, soldiers, and newspaper clips of Israel’s successes in the realm of war. “I feel safe when I look at them,” she tells Sivan. The camera alternates between close ups on Varda’s face and medium shots of the area exterior to the café. During the latter, we see across a divided highway the razed landscape of what was formerly an Arab village, Masmiye. The tenor of the interview with Varda reveals a simultaneous denial and cognizance of the role of the colonial project. This duality is jarring for its frequent occurrence in the interviews with Israelis.

[Scene from Varda’s café]

Khleifi and Sivan strive to capture the dissonance between the history of the Israeli occupation and the narrative presented by those who have benefited from it. We hear Varda’s voiceover describe the area’s two remaining Arab families as “squatters” while the camera roams the walls of her café, which serve as an unofficial archive of Israel’s systemic violence. The camera returns to her and she becomes bashful, stating that she knows Sivan, “like all the media,” sides with the Arabs. Captured on film is Varda’s vision of what it takes to live together, something she thinks is impossible — hence her stated desire to pay Arabs, “even the Israeli ones,” to leave. At the end of this scene, Sivan’s voice comes in from offscreen, asking her, “So, there’ll never be peace?” Varda responds with a chilling clarity whose poignancy seems to escape her, “Never. Not as long as we’re here.”

[The proprietor, Varda, serving one of her customers, an Israeli soldier]

In the second section, “Center,” the “we” shifts to signify a group of elderly Palestinian men gathered in a barbershop. Almost as though in response to the “we” of Varda’s formulation, this sequence seems to want to say, “The catastrophe will never be forgotten. Not as long as we are here.” The men remember the events of 1948 as they played out in the town of Lod. They recall the expulsion of 50,000 Palestinians who became refugees in Jordan. The barber sets his memory – and that of his friends and relatives – against officially accepted narratives. What he remembers of 1948, when he was nineteen years old, is violence and forced migration. “Yigal Allon’s book is nothing but a collection of lies,” he says, in reference to the Israeli general who was instrumental in several key operations in 1948. His recollection of the events contests what Israel needs its citizens to believe: that the Palestinians left willingly.

[Palestinian barber in his shop]

[Giving a haircut while recounting the violence of the nakba]

While the barber begins telling Khleifi what he witnessed in 1948 when the Israeli Defense Forces entered Lod, the camera focuses on his face, as he moves around the man’s head, reaches for a comb, and performs other gestures. We never see the customer’s face, nor do we have access to the barber’s friends who are sitting in the same room and who had, up until this point, also been involved in asserting that they remember Lod and 1948 in the same way that he does. We hear the whir of a cheap fan, the only source of comfort in the room other than the ability to retell this story to the camera. Khleifi and Sivan are careful to draw attention to the fan. Its spinning is made prominent on the sound track and there are several close up shots on the device. It is also the last shot of the barbershop, a grim reminder of the ersatz nature of a life of poverty under occupation. As the Palestinian barber cuts his customer’s hair, the fan occasionally sweeps his own hair off his face. He is telling a story about being forced to watch six Israeli soldiers rape a young mother. He is slow and deliberate in the way he narrates. The camera leaves him, finally, and rests on the face of his friend and the man who led Khleifi and Sivan to the salon. He is silent as he remembers the nakba, while witnessing the barber remember it and while witnessing Khleifi and Sivan learn about it. In the still below, the wind from the fan threatens to disrupt the image, but the face of the man in the act of remembering allows it to only leave a trace.

[Remembering the nakba]

Route 181 employs all possibilities of the route - marked, fragmented, nonexistent – in exploring the non-linear mode of memory, truth, and knowledge operative in personal and collective ways of dealing with Zionism. The places where the road does not physically exist – or a town does not physically exist – and where the new residents nevertheless remember the towns’ original names – attest to the audacity of pushing one truth about Israel (a celebration of its “independence”) while attempting to deny its role in the nakba, in catastrophe.

Roadmap for Peace?

It is perhaps unsurprising, given the film’s questioning of the legitimacy of Israeli settlements and the way it acknowledges the history of violence that enabled them, that Route 181 faced significant roadblocks to its own dissemination. In 2004, the organizers of Le Festival du Cinéma du Réel, held annually at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, cancelled one of the film’s two scheduled screenings, arguing that what they deem the film’s “underlying hostility to the existence of Israel” could provoke the proliferation of anti-Semitic sentiments and actions in France. The French Ministry of Culture supported the decision, citing the screening of the film as a potential risk to “public order.” The filmmakers responded immediately with a letter that named this an act of censorship and demanded a retraction. They later circulated a petition of support from over 100 prominent intellectuals and filmmakers.

The origin of the controversy in France is rooted in a scathing critique made on public radio by the philosopher Alain Finkielkraut, who argued that the film was an “incitement to hatred.” For Finkielkraut, Sivan’s role as filmmaker amounted to an act of “Jewish anti-Semitism,” particularly for the film’s alleged comparison of the nakba to the Holocaust. Central to the latter criticism was the claim that Khleifi and Sivan had plagiarized Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 Holocaust documentary, Shoah. At question was the scene featuring the Palestinian barber’s testimony of the massacre at Lod, which offended Finkielkraut (and others) because of its citation of a famous scene from Shoah, in which a Jewish barber recounts his experience at the Treblinka camp, where he was forced to cut Jews’ hair before they were sent into the gas chambers. The accusations resulted in Sivan filing a libel suit against Finkielkraut which went to trial in 2006.

Route 181 fared no better in the United States, where it was the subject of negative reviews likening it to propagandistic film making. This was, however, only two years after the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences rejected Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention as Palestine’s official entry in the foreign film category, arguing that by UN standards, Palestine is not “considered” a country.

The film’s implicit understanding that once it is released it becomes one part of the media discourse on Palestine-Israel is evidenced by its heightened and consistent awareness of itself as a text. My reading of the film situates this awareness in an attempt, on the part of the filmmakers, to demonstrate the ways in which historical knowledge can be elided through calculated narrative reconstructions. Almost every Israeli interviewed in the film demonstrates, in his or her answers, how the narrative of Israel’s right to expansion rests heavily on a willful amnesia concerning the existence of Palestine and Palestinians. The approval of the so-called “Nakba Law” by the Knesset is certainly influenced by and constitutive of this Israeli national consciousness captured by Khleifi and Sivan’s camera.

Although the word “nakba” does not actually appear in the wording of the new law, the bill is clearly aimed at dismantling the idea that the nakba is a historical truth. Before getting amended in the Knesset, the original version of the bill aimed to enforce a prison sentence for anyone who treated the Israeli Independence Day as a day of mourning or held memorial events related to the nakba. The adopted law is more ambiguous, and pernicious, in its exclusion of the word “nakba” and subsequent emphasis on the way Israel’s Independence Day is marked. Yet there is nothing, even in official discourse, which attempts to maintain the pretense that this is about anything but the threat of Palestinian collective memory. Alex Miller, the member of the Knesset who sponsored the new law, said in an interview with Haaretz on 24 March 2011, “I view Independence Day as a state symbol, but from an early age, some citizens of Israel are taught to view this day as a day of mourning! So either we want education for coexistence and peace, or we want pupils to be brainwashed and incited against [other] citizens of their state from an early age."

Despite the Knesset’s attempts to shift the focus from the nakba, the law has become known in popular discourse as the “Nakba Law,” thereby marking the significance of the word for the grounds of the debate over the law. The impossibility and irony of the “Nakba Law” is lost on Israel’s legislators. Daily catastrophe continues to be the law of the land in Israel, and by simply invoking the name “nakba” as counter to official discourse, their attempt to make memory disappear only works to underscore the potency of “catastrophe.” It is the myriad, daily occurrences of “catastrophe,” to which the film plays witness, which make the signifier relevant.

It should not go unmentioned that the passing of the “Nakba Law” coincided with the Admissions Committee Law, which allows Jewish communities in Negev and Galilee to vet potential residents via an admissions committee. The law applies to communities with fewer than 400 families and gives the admissions committee the power to reject potential residents who do not fit in with the community’s “social or cultural way of life.” Here, on the terrains of contested space, the state of Israel yet again demonstrates its own desire to control difference at an affective or emotional level.

The importance of revisiting Route 181 today and deeming it a forgotten classic of Palestinian and Israeli cinema is contained in the film itself. As a text, Route 181 forces its viewers to sift through the disparate truths and historical conditions of existence for both Palestinians and Israelis. It dares us to perform a deceptively simple task by asking how we can move forward without full vision of the road that led to our point of departure.

Route 181: Fragments of a Journey in Palestine-Israel is available on DVD from Sindibad Films.