When I first accepted the challenge of drawing the Kafr Qasem massacre, I wanted to represent its events as though I were a camera on site. Documentary drawings, I thought, could recreate what photography might have given us if done on a historical basis. I would learn all I could and present the specific individuals and the documented events. I worked on the project in three major periods, each occupying most of a year or several years. I began work in 1999 and continued into 2000. In 2006, on the occasion of the fiftieth memorial of the massacre, I created both a web page and an exhibition of the drawings. In 2012, I returned to the project with the intention of finalizing it by making large-scale drawings and developing a book.

The story of the Kafr Qasem massacre is compelling. At first hidden from the world, it was members of the Communist Party who broke the military and information blockade in order to call attention to the horrific massacre; a detailed press release was finally published by party member Tawfiq Toubi twenty-six days after the massacre on 23 November, 1956 in Arabic, English, and Hebrew. His comrade, the distinguished Palestinian writer, Emile Habibi covered the massacre in issues of the CP organ, Al Ittihad, and in 1976 published a booklet on the subject. In one chapter, Habibi recounted the events and provided a structure whereby the chronology of events were numbered and termed “waves” of killing.

Israel’s military campaign against Egypt and the Suez started at 3pm on 29 October, 1956. One and a half hours later, at 4:30pm, the mukhtar (mayor) of Kafr Qasem was informed of an imminent curfew to begin at 5pm. Twenty-five minutes after this sudden warning, at 4:55, soldiers of the Israeli Border Police began killing anyone they found outside their home—be they man or woman, child or elder. Many were workers unaware of the curfew, as they were just then returning home. At the end of the night, forty-nine civilians lay dead on the roadways. Although each event of the massacre was nightmarish, the last one seemed to shock the villagers most of all, as fourteen women who had been olive picking were forced off a truck and shot at continuously from close range until they all fell dead over each other. The sole survivor of this wave of killing was a fifteen-year-old girl, who, when heavily wounded, lost consciousness, and lay under the corpses of the other women for most of the night. To add terror to brutal injury, the Israelis buried their bodies while their relatives were imprisoned in their homes on pain of death through the use of a twenty-four hour curfew.

A massacre is like a hammer blow that shatters a hard mass to smithereens. At first the pieces, the individuals who suffer this blow, do not all see who wields the hammer nor are they able to attack it. Anger and blame are bottled up. Painful energy flies in all directions. The town receiving the blow is shattered, broken to pieces, and as the pieces settle, loss, recrimination, shock, disbelief, and desperation emerge. Added to all this, as in the case of the Kafr Qasem massacre, is the poverty and depression resulting from a brutal military occupation.

What does a father tell his wife when he returns home alive but their eight-year old child whom she sent to warn him dies in the massacre? Why is a small girl unable to tell her mother that her father lies dead or wounded in the street except to say that dinner need not be prepared for him? Why do men and women, unable to believe their own experience, return to the scenes of the massacre to confirm its reality with those who shared it only to find death instead of fellowship? Why was the only survivor of one of the events of the massacre insensitively asked why she was the only one to survive? Why does a wounded man who had escaped, return on seeing the Israeli soldiers killing fourteen women only to be shot dead himself? Why did some whisper that the pregnant woman in her final month dropped the baby in the agony of her death?

When I first met Aishy Amer of Kafr Qasem, the beautiful scent of revolution permeated her words and manners. We had met through the internet and from her first visit to my loft she began to persuade me that, as an artist, I must do drawings of the massacre. Aishy and I eventually visited Kafr Qasem together, where she introduced me to her large family and friends and opened the way for me into a tightly knit village society made up of only five extended families. Following this first visit, she would assign her friends to help me. After interviewing some individuals several times over a period of thirteen years, they came to trust me as a friend. In fact in 2012, during my last visit to attend the annual memorial march, I found myself receiving extended interviews while members of the press were disregarded.

Along with my interviews, I conducted extensive research for historical materials and found a gold mine in the locally published magazine, Al-Shorok, each October issue of which is dedicated to the massacre. In it are countless long interviews conducted by Majd Sarsour, editor and principal of one of the town’s high schools. In general, the outside press did not match this valuable source of detailed information. It was rare to find newspaper articles that contained more than small bits of quoted information. Yet Al-Shorok allowed each individual to fully tell his or her story. Al-Shorok also insisted on detailing not only the names of victims and their ages, but also those of their children, the gender of the children, and their ages at the time of the parents’ death. In one particular article, the magazine detailed the ages of over four thousand offspring of the victims who had already given birth. An intense need to replenish the village overtook the survivors.

I came to truly respect the village, now grown into a town, regardless of its various types and admire the combination of earthy nobility, innocence, and wisdom they possessed. I learnt of the depth of pain they experienced, causing many to be unwilling to tell their stories. I learnt to value their trust and grew to understand that documentation should respectfully memorialize, avoiding sensation and spectacle.

I began drawing immediately after the first visit and continued to do so in separate periods of intense focus. As I worked and my knowledge grew, many of my initial aesthetic decisions matured. I determined that I would avoid simply showing piles of dead bodies. I would show people in their dignity at the last moments of their life. There would be no blood. I determined that the individual victims should face out towards the viewer, be in control of the aesthetic situation if not the original situation, which brought their violent end.

I began drawing in an illusionist way in the traditions of Renaissance art, but as the project progressed, I often questioned whether I perhaps should use an expressionist method. I admired Diego Rivera and thought that working in that manner, which many of the Palestinian artists of the Intifada were influenced by, might be a more modern path. However, after a lot of thought, I decided that the expressionism and semi-cubist style of Rivera did not suite the ambition of presenting people as specific individuals in documented events.

There is a paucity of visual information on the massacre, leaving written material as the basic source. Transforming verbal description and researched information into visual images presented serious problems. Words can focus on one subject and describe it accurately but not wholly. Pictures describe a scene wholly (from one point of view) but cannot show what happened just before or after. Pictures lack the specificity of time while words lack the specificity of space.

Truthful witness statements can hold up in a court of law but they lack the type of information pictures need regarding the appearance of a whole scene, information about color, light, background, relative positions of parts, and a host of other scenic details. This forced me into a certain amount of invention, which seriously conditioned my ambition to be a camera.

One of my initial inquiries was how to represent the killers, the soldiers of the Israeli Border Police who had executed the massacre. Based on things that I have seen in Palestine combined with my loathing, I made several horrifying renditions. In the end, I decided that the story was not about them and eliminated them from the drawings. However, in the final set done in 2012, I included fragments of them in outlined silhouette although I rendered their weapons carefully. By then I had researched the weapons and noted that they were semi-automatic weapons and that some of them were British made, reminding me of the part British colonialism had in arming and organizing the Zionist terrorists.

I asked for a great deal of criticism from residents of Kafr Qasem and from friends, and their opinions helped me greatly. I was not on a research mission to discover new formal languages but rather on a mission to tell a piece of Palestinian history in comprehensible visual form. I received a rating of seventy over one hundred on my drawing of the sixth wave of killing. I was flattered to have such a high grade for the man grading me, Omar Ahmad Hamdan Amer, known as Abu Naser, was the town’s historian, a man who lived his entire life immersed in the history of the massacre.

Did I meet my own challenge? An inner voice says: do it all over again and do it better. But another voice says: another way to fail is to disregard time. For now, I will be happy when my planned publication of drawings on the subject of the massacre is complete. The book will be called “Drawing the Kafr Qasem Massacre.” It will include a detailed history, a timeline, numerous witness statements, the drawings with my commentary, a roster of victims, and essays by scholars.

Below is a selection of drawings from the series with the artist`s captions:

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, Killing Inside the Village, the Easa Family (1999).]

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, Killing Inside the Village, the Easa Family (1999).]

During less than two hours on 29 October, 1956, Israeli Border Police killed forty-nine people in the Palestinian village of Kafr Qasem. They were mostly workers and children returning home in the evening. Most were killed on the western entrance, while inside the village it began when eight-year-old Talal Easa went out to retrieve a goat after the suddenly announced curfew. Talal’s father, Shaker, heard the shots and dashed out to his son. He was also shot. Talal’s mother, Rasmiyya, and, right after, Talal’s teenage sister, Noor, ran to their bleeding family and suffered the same fate. They remained where they fell, bleeding until morning when they were hauled off by truck to a hospital. Talal died. The grandfather, Abdallah Isaa, then ninety years old, was left alone and saw the massacre of his family. The following morning, Abdallah was found dead.

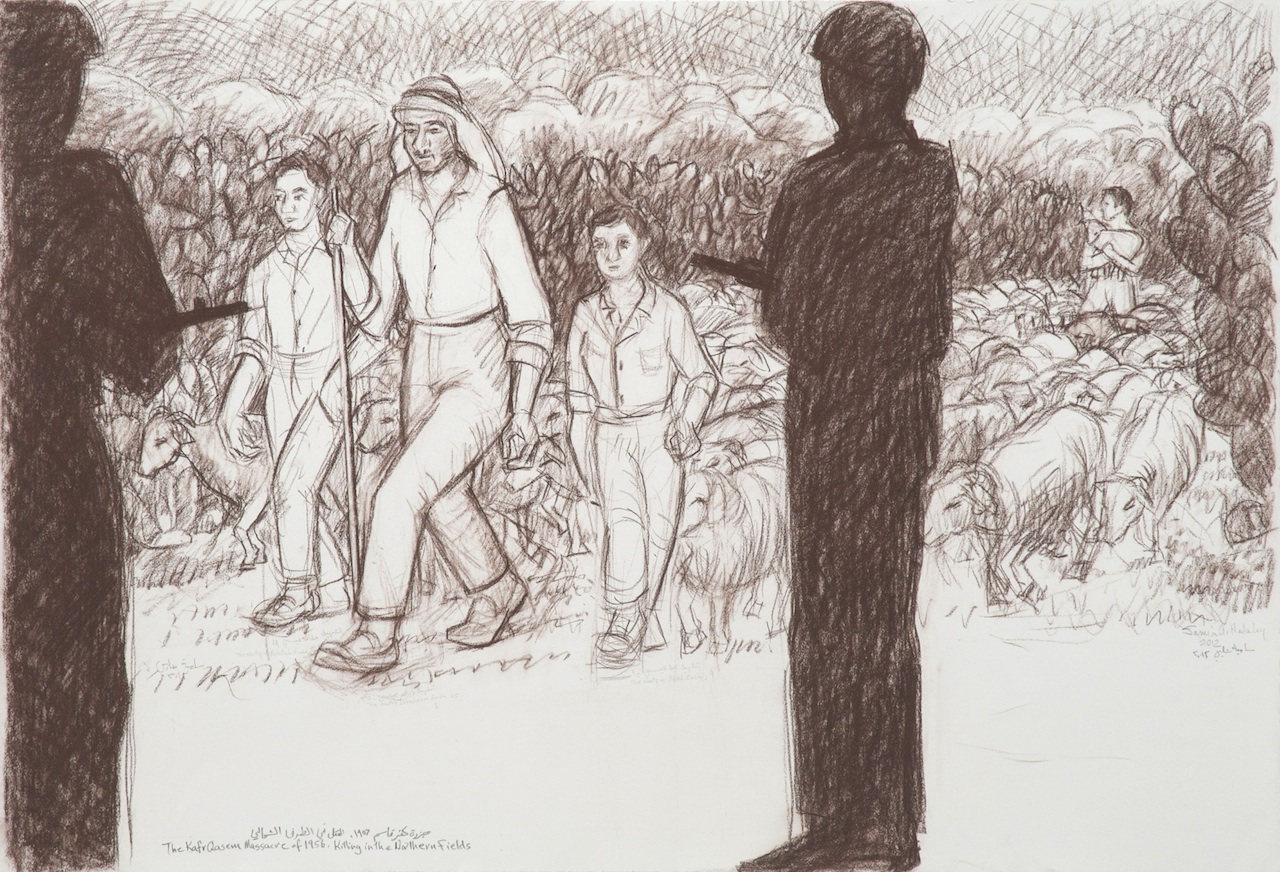

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, Killing in the Northern Fields (2012).]

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, Killing in the Northern Fields (2012).]

In the northern fields of the village, three shepherd boys were out watering the family’s flock of sheep not knowing that Israel had launched a surprise attack on Egypt just hours before, nor did they know of the curfew imposed on their village. The oldest boy, Abdallah Easa was sixteen and the youngest, Abed Easa, was nine years old. Ibraheem Easa, their uncle who was thirty-five years of age, had learnt of the curfew and left the safety of his home to bring them back. They returned immediately with Ibraheem leading. Abed and Abdallah were just behind him while the third boy, Sami Mustafa, was watching the rear of the herd. The boys were met by Israeli soldiers of the Border Police, who immediately shot and killed Ibraheem, Abed, and Abdallah. Sami saw them being shot and fell to the ground, played dead and survived.

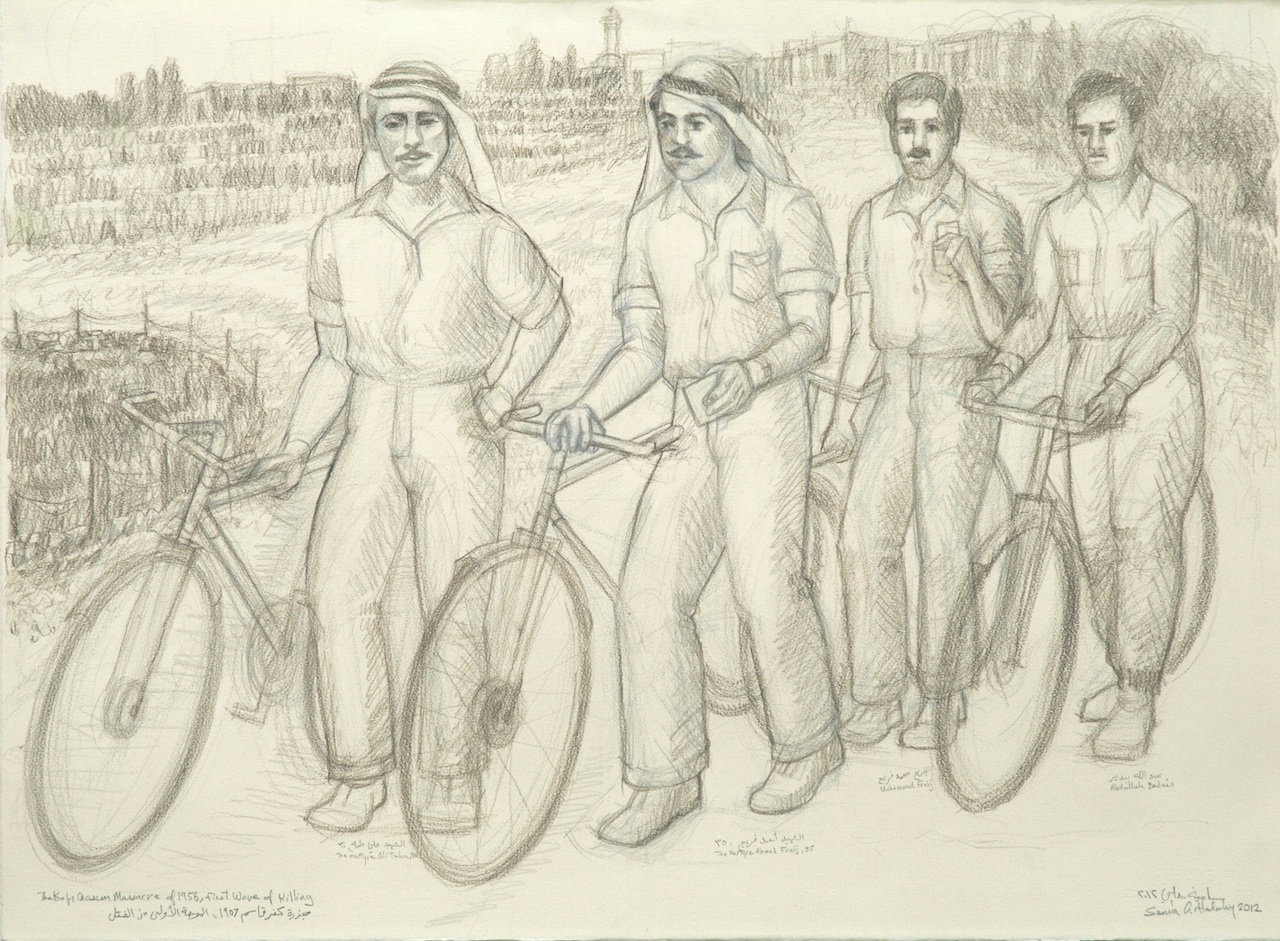

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre, the First Wave of Killing (2012).]

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre, the First Wave of Killing (2012).]

Five minutes before the curfew, and unaware of it, four quarry workers were returning home to Kafr Qasem on bicycles. When confronted by Israeli soldiers, with whose harassment they were familiar, they reached for their identity cards. Instead, an order to "harvest them" was given. Two, Ahmad Freij, age thirty-five, and Ali Tah, age thirty, died. Both were fathers of young children. Two others, Mahmoud Freij and Abdallah Badair, managed to escape. Mahmoud was wounded in the thigh and managed to crawl to an olive tree and hide until morning.

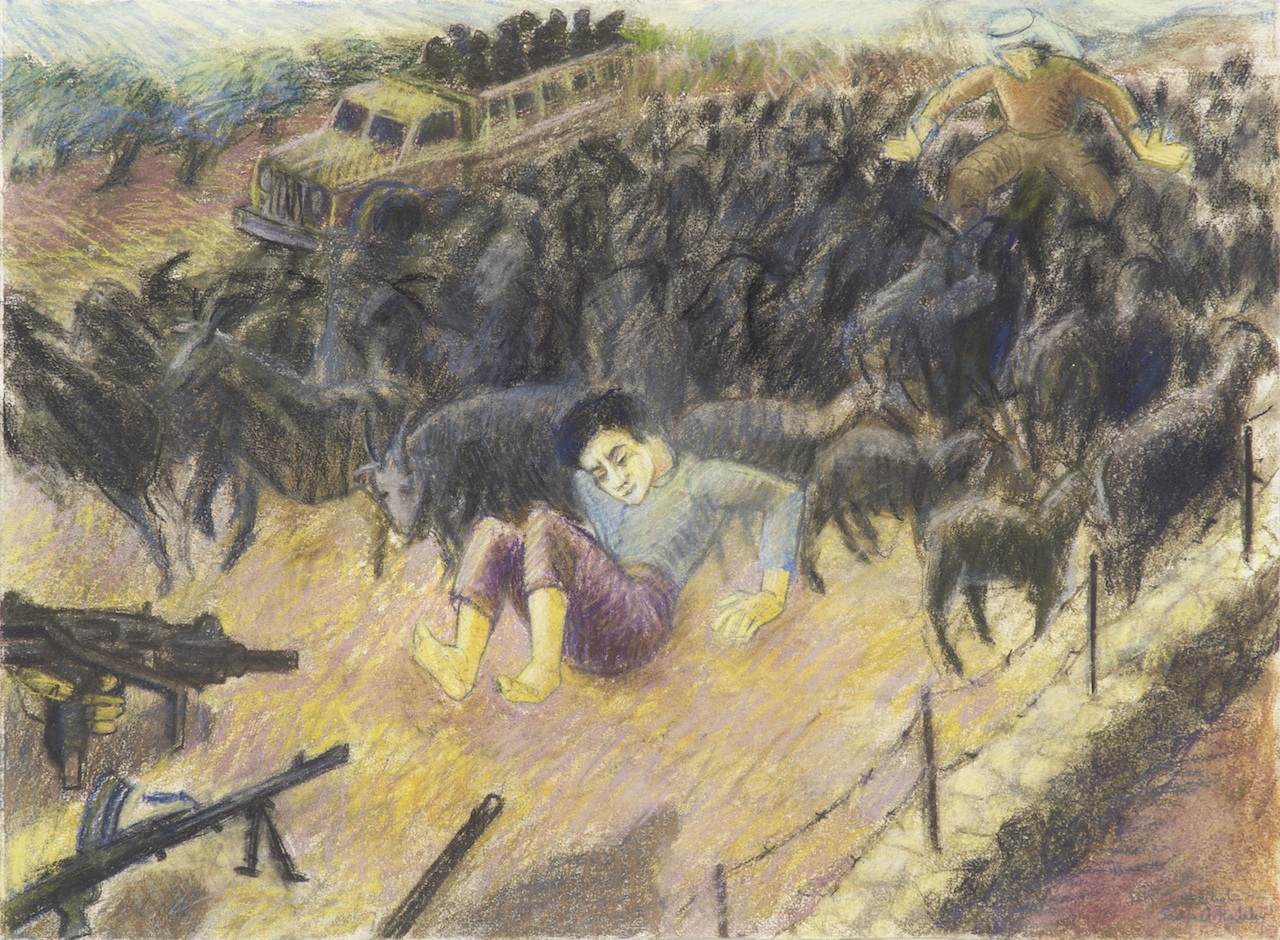

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, the Third Wave of Killing, Child Fathi (2012).]

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, the Third Wave of Killing, Child Fathi (2012).]

The twelve-year-old shepherd boy, Fathi Easa, was leading his family’s herd of black goats home after pasture. His father was driving the herd from the rear having heard of the curfew and had come to hurry his son home. There were three weapons in the hands of the Israeli Border Police all aimed at the boy, an Uzi, a Bren, and a rifle. All were fired, and the boy collapsed and died.

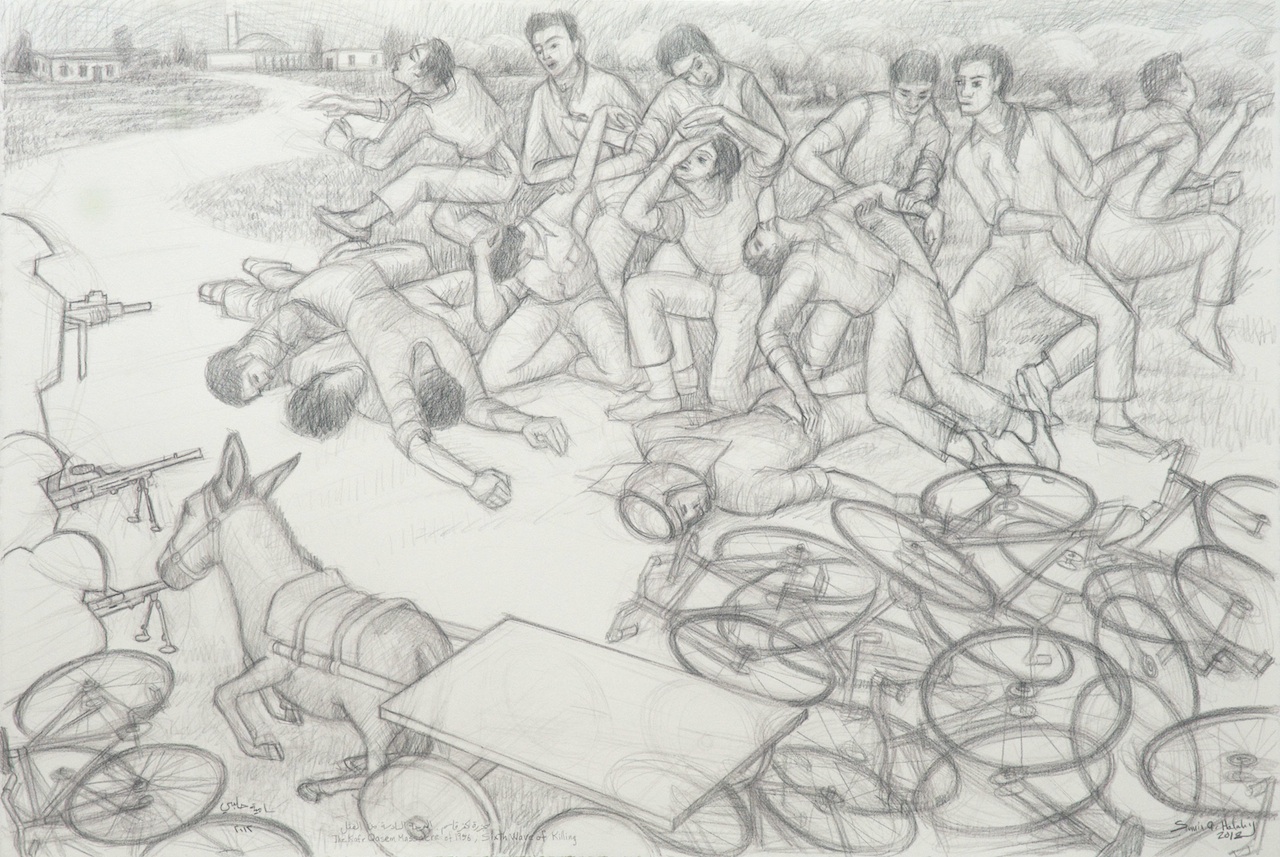

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, the Sixth Wave of Killing (2012).]

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, the Sixth Wave of Killing (2012).]

Evening was darkening as the Israeli Border Police ordered thirteen or more workers to lineup on one side of the road. They had arrived on bicycles and a mule wagon. One of the workers, seventeen-year old Saleh Easa, had arrived with his two cousins. They had heard about the curfew and only feared a beating. When the execution style shooting began six fell dead. Saleh, wounded, playing dead, was dragged to the pile of bodies. He remained quiet, gritting his teeth in spite of extreme pain. He witnessed the rest of the massacre and later crawled to safety.

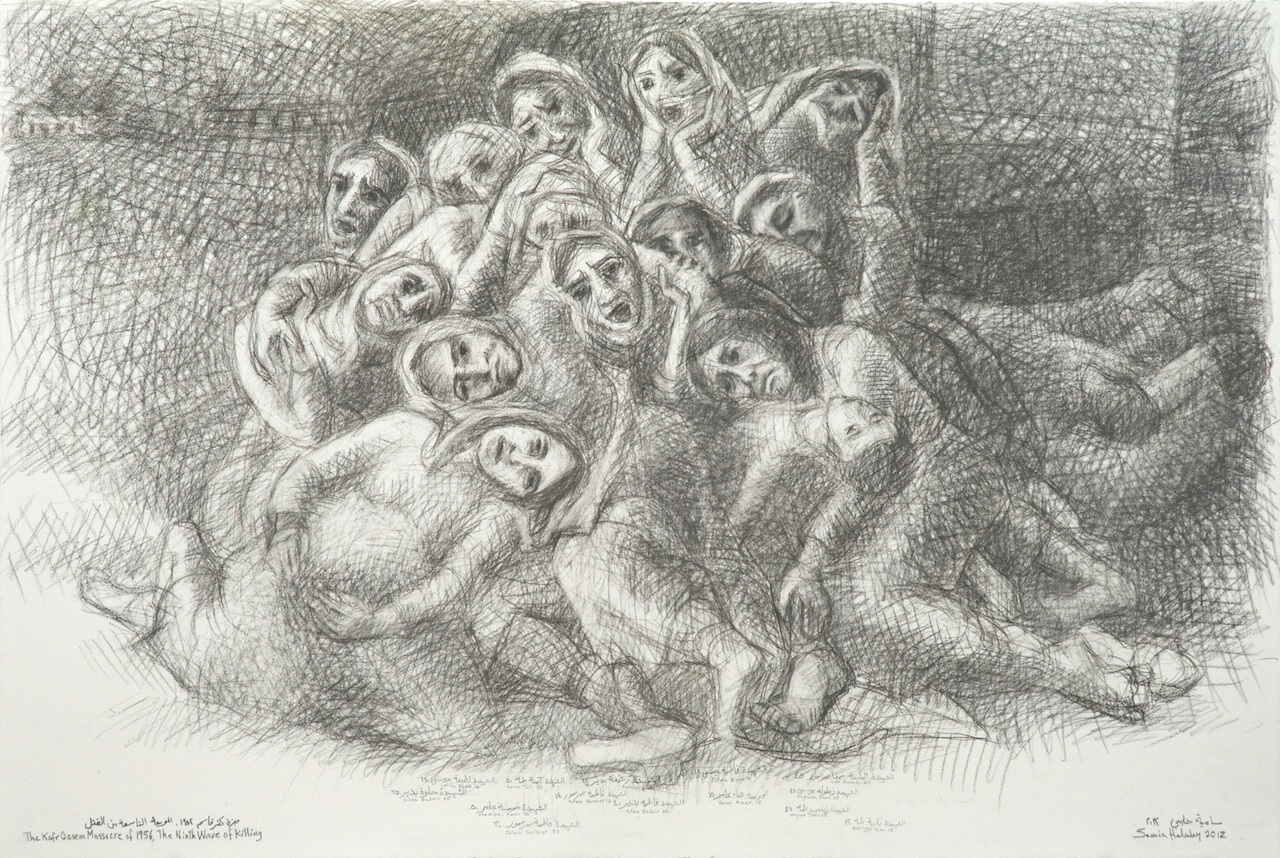

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, the Ninth Wave of Killing, Implosion (2012).]

[The Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956, the Ninth Wave of Killing, Implosion (2012).]

Night had fallen when the truck arrived at the location of the massacre. Among the victims of the ninth wave were two men in the cab of the truck and fourteen women with two boys in the back. The driver, seeing the scattered dead, tried to escape at high speed. This interrupted the singing women, who unwittingly began to scream, thus alerting the recumbent soldiers resting at the school’s well. The soldiers ran after the truck, shot its tires and gas tank, and stopped it. Safa Sarsour, having just seen her sixteen-year-old son, Jum’a, dead on the side of the road, now witnessed her second son, fourteen-year-old Abdallah, being killed with the men. The women, some pregnant, elders and girls, pleaded for their lives. The only survivor was Hana’ Amer, fifteen years of age, who said that the women clung to each other for protection, even the two girls who had managed to escape returned to the circle. As they were being shot, they turned in a big group and one by one they fell. The soldiers continued shooting into their heads to insure their death. How does it measure western civilization when soldiers of the Israeli border police line up defenseless women—some pregnant, tired, returning home from work—and kill them with cold deliberation?

*All images copyright the artist.