Arna’s Children. Directed by Juliano Mer Khamis and Danniel Danniel. Israel-Palestine, 2004.

It has now been two months since the murder of Juliano Mer Khamis. I have not yet found the words to follow that statement. For me, as for many, the horror of this assasination has compelled a revisiting of Arna’s Children, the masterpiece Juliano made with Danniel Danniel in 2004.

I will not follow standard practice here and provide a plot summary. If you have not yet watched this film, stop reading now and watch it. (And once you have watched it, buy a copy of the DVD to help support The Freedom Theater.)

I first wrote about Arna’s Children as part of a review essay for Arab Studies Journal in 2005. I find that many of the same thoughts still apply to the film as I watch it today. What still strikes me the most is how unsparing a vision Juliano presents to us. This is perhaps best marked by a moment midway through the film, when Arna, a figure we might expect to be treated with the reverence given to a saint, suddenly begins talking about her role in the Palmach as a young woman in 1948. Most of the exploits she recounts, like driving a jeep barefoot along the sidewalk while people jumped out of the way, she attributes to the “wildness” of youth and to the fact that “at that age, everything seems beautiful.” Is there anything she is ashamed of? Nothing, she says without hesitation. Then: “No. I helped to drive out the Bedouin. That is something I regret. Yes, I did that,” she concludes, staring straight into the camera. The rest, she repeats, was wild youth: “I was adventurous, that’s all. I did no harm.”

The viewer cannot but be overcome by the frankness of this confession, and by Arna’s otherwise adamant refusal to take part in the easy rituals of apology to which we have become so accustomed. This shock marks the extent to which we have become programmed to expect, or perhaps demand, certain forms of sentimentality and easy pieties in our preferred narratives about Palestine. What the sterotypical script would call for at this point would be Arna’s tearful mea culpa, the renunciation of her role in the Zionist violence of 1948, and the concomitant assurance that her work with Palestinian children in Jenin is an attempt to atone for the sins of the past. This is a narrative of guilt and atonement with which we have become all too familiar. Instead, we get the exact opposite: the strong sense that for Arna, the wildness of her days in the Palmach and the wildness with which she attacks the Occupation are of a piece. It is this same wildness, as we see throughout her work in Jenin, that she exhorts upon her young charges as she encourages them to fight against the injustice in their lives, the same wildness that Juliano will encourage in his theater students and that stil marks the fearless aesthetic experiments espoused by The Freedom Theater today.

But Arna’s Children never lets us forget the powerful forces of death arrayed against this wild revolt. From the first moments of the film, in which Arna, left bald from chemotherapy and sporting her ever-present kafiya, leads a vocal protest against a checkpoint outside Jenin camp (exhorting the drivers in Arabic, at the top of her weakened lungs, to simply drive past the IDF soldiers, and to lean on their horns as they do so), death is always in the foreground. The viewer is immediately aware that the film will take as its point of departure a historical event as inexorable as Arna’s approaching death: the 2002 Israeli invasion of Jenin camp, one of the foremost atrocities of the Occupation, which left behind a wake of death, crippled bodies, destroyed houses and dreams. Early in the film, the camera flashes back to a performance of the Jenin children’s theater in 1994; after the applause, an interviewer asks Arna how much longer she will be able to continue her work. “Listen. Either the project finishes me or I die before it is finished,” she barks. Arna’s Children returns to Jenin to witness, in the aftermath of the ever-increasing brutality of the Israeli Occupation following the second intifada, what has become of “the project.”

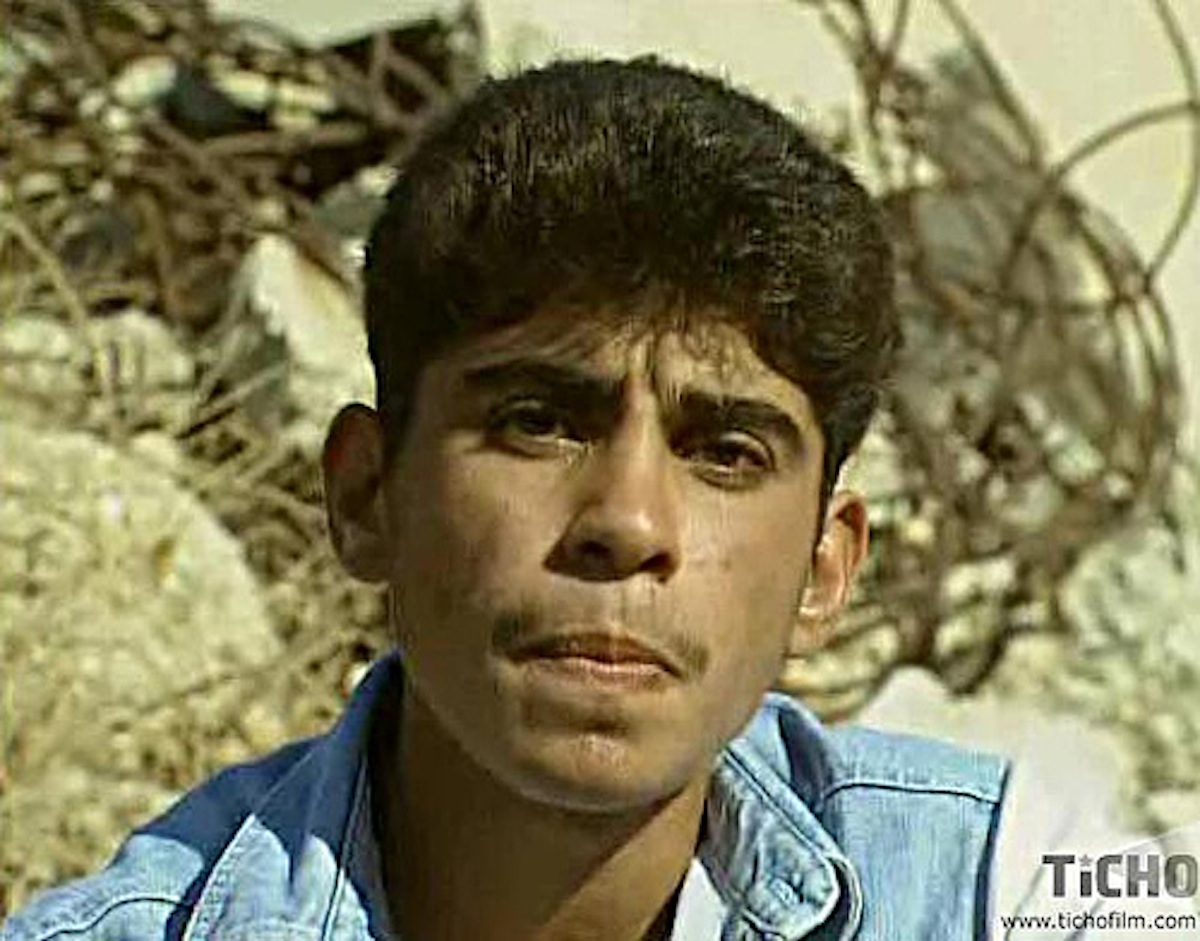

The film does not constitute a simple, straightforward narration, nor does it wring its hands over the “lost” moment of Oslo, as so many narratives of its time tended to do. Much of the first half of the film consists of footage shot during theater rehearsals and performances in Jenin from 1989 to 1996. Even though the camera in these scenes rarely leaves the theater, it is nevertheless obvious that the constitutive fact of these children’s lives is the relentless violence of the Occupation. The most recurring and haunting image of the film is a shot of ‘Ala’ sitting atop the ruins of what had once been his house, after Israeli Occupation forces demolished it. The haunted eyes of the eight-year-old ‘Ala’ are immediately recognizable when we meet him again in 2002, soon after the invasion, as one of the local commanders of the Al-Aqsa Brigades and a veteran of the battle of Jenin and of subsequent resistance efforts against Israeli Occupation forces.

This is the film’s central focus: what became of the children who were members of Arna’s theater project? While it is that single image of ‘Ala’ that is the most iconic, it is the presence of Youssef in the past, and his absence in the present, that inspires the film’s sharpest juxtapositions of before and after. In an interview shot when they were all young teenagers, Juliano asks Ashraf, Nidal, Youssef, and several others about their first encounters with Arna and himself. The boys cheerfully admit that at first they assumed that Arna and Juliano were spies (hardly paranoia, for anyone who knows anything about the efforts of Israeli intelligence forces in the West Bank). It is Youssef who gives the most thoughtful explanation for this assumption: describing his doubts about why Israeli Jews would come and set up a theater troupe and other educational programs for children in Jenin, he declares, to Juliano and to the camera: “I asked myself, why isn’t there an Arab who would do this for us?” “Don’t be angry,” he adds, turning directly to Juliano, “I love Arna like my own mother” (and adds “even a little more”). The camera makes a direct jump cut from this statement to a shot of Youssef, now grown, in full military attire, addressing a different camera in the video he made just before carrying out his suicide operation. The cut is marked on the soundtrack with the sound of an automatic weapon being loaded, the audible click as the cartridge locks into place.

To its credit, however, Arna’s Children never simplifies this relationship between past and present: that is to say, it has no illusions about the jump we see here being some sort of move from “peace” to “war.” One of the most moving aspects of Arna’s project is that it views art, theater, and other forms of cultural and educational work as forms of resistance. Far from being a simple and depoliticized form of “self-expression,” the artistic efforts of young people, as represented by this film, are actually part of a larger effort to imagine new ways of living, new communities, new futures. When ‘Ala’ comes to the community school the day after his house was demolished, Arna insists that he and Ashraf (who lived next door, and whose house was also partially destroyed by Israeli forces) talk about what had happened. “What do you want to do to the soldiers?” she asks Ashraf. “Kill them,” he replies. Arna then offers up her body for them to push and punch, asking them to pretend that she is one of the soldiers. In the face of the Occupation, “be angry,” she insists. The theater exercises presided over by Juliano have the same nature: not an attempt to therapize or by-pass anger, but to precisely find that anger and bring it into the performance. It is clear that part of the reason why these young people embrace the theater is that it allows them to insist on their existence even in the face of an Occupation determined to deny them this existence by every means possible. Ashraf, describing why he had continued working with the theater when he was a teenager, tells Juliano that it gave him “things I could use for the future.”

When the camera returns to the camp to find the theater, like most of the buildings, utterly destroyed by Israeli tanks and bulldozers, it is clear that what the Occupation has attempted to destroy in Jenin are precisely the forms of resistance that Arna’s project represented. In the face of the pure violence of the Occupation, a violence that has destroyed all other avenues with which to express even the right to exist, the only possible response that appears to these young men in Jenin is violence, even suicidal violence against overwhelming odds (the film ends with the death of ‘Ala’ at the hands of Israeli Occupation forces). In showing what happens when it is removed from the scene entirely, Arna’s Children thus makes a strong and moving case for the necessity of art in any form of resistance that wants to imagine and bring into existence a different future.

Watching Arna’s Children today, it is the beauty and humor of this film that becomes most apparent. The scenes of the children’s performances and rehearsals are extraordinary, and the contrast between past and present made all the more devastating as a result. At one point, the camera cagily captures an Israeli interviewer who comes to do a television news piece about the children’s theater: as the interview proceeds, the kids find ways of using their theatrical talents to play with the interviewer’s stereotypical expectations (especially Youssef, who uses his quite good Hebrew to confuse the interviewer, for example by referring to himself as “Yossi”). The relationship between violence and humor, and of humor as a form of resistance, hovers throughout: at one point, several boys put on a skit parodying their English teacher, which consists largely of the boy playing the teacher beating the others for showing insufficient respect. “OK, that’s enough,” Juliano shouts, and his young actor yells back, “Wait, I’m not finished,” before administering a few more blows to his pupils. Like much of the film, the effect is quite funny, even though what is being represented — the saturation of these children’s lives with violence — is also quite horrifying.

When I first wrote about the film six years ago, several readers, whose reactions I trust a great deal, told me that they completely disagreed with my suggestion that there was anything funny about that scene. I accordingly cut this from my review. A year or so later, I attended a screening of the film, and found myself laughing along with the rest of the audience while watching the scene. I say this not to vindicate my original reading, but rather to highlight the difficult set of feelings that the film leaves us with. The scene is both horrifying and funny, and all the more horrifying, I would argue, for its humor. Once again, the refusal of sentimentality makes itself known both aesthetically and politically: we expect to be given this insight into violence in the tragic mode, and when it comes to us in a form that leads to laughter, we are shocked, taken aback, literally made to think again in a way that the accustomed sentimental mode actually works to soften. “We laugh,” as Nadine Gordimer once wrote about the work of the great Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, “and then catch our breath in horror.”

It is this presentation of humor, this refusal to move into a mode that is too easily tragic, that makes Arna’s Children distinct from most films about Occupied Palestine and that in part accounts for the extraordinary effect this film continues to work upon its viewers. Theodor Adorno, in his great essay “Commitment,” warned against works of art, even well-meaning ones, that “turn suffering into images” and thereby cannot help but also turn this suffering into a form of enjoyment for an audience to consume at its leisure. In these “tragic” works, the victims of suffering, Adorno writes, “are used to create something, works of art, that are then thrown to the consumption of a world which destroyed them. The so-called artistic representation of the sheer physical pain of people beaten to the ground by rifle-butts contains, however remotely, the power to elicit enjoyment out of it.” The common denominator of most of the works that fall into this trap, Adorno concludes, is the simplistic insistence “that even in so-called extreme situations, indeed in them most of all, humanity flourishes . . . the distinction between executioners and victims becomes blurred; both, after all, are equally suspended above the possibility of nothingness, which of course is generally not quite so uncomfortable for the executioners.” [1]

A few minutes after arriving in Jenin camp, just days after the Israeli invasion — it is the first time he has set foot there in several years — Juliano encounters several women who have just returned from Ashraf’s funeral. In the midst of their conversation, as the women fondly remember Arna and her work in the camp, one of them begins to laugh. Juliano starts to walk away, then turns to her. “How can you still laugh?” he asks, genuinely baffled, looking around at the ruin and destruction that surrounds them. “We are strong. We will survive,” she responds. It has become by now a commonplace to note that Palestinians living under the Occupation continue to laugh, and this is often used to mark their continuing “humanity” — as if it needed to be continually stated and re-stated that those living under occupation are, in fact, human beings. This is, apparently, meant to be viewed in and of itself as a victory, of the “life-goes-on” sort described by Adorno. But the fact that laughter itself needs to be made conscious and thrown back in the face of the occupier, that it needs to be extolled and held up as an example of survival, that it needs to be heard and cited in order to have one’s very existence acknowledged, is the most tragic thing imaginable. Arna’s Children succeeds in representing this tragic laughter, as a marker of the absolute dehumanization that is the essence of occupation.

For the biggest danger for a complicit audience (and in the case of a film about Palestine, this sense of complicity applies not just to an Israeli audience but also takes in, very directly, the American audience whose government underwrites and manages the suffering being portrayed) is that the sheer fact of viewing the film can come to seem like an act that somehow addresses the suffering that has been represented. One goes to view suffering, one cries one’s share of tears at the “tragedy,” one goes home feeling cleansed and somehow superior to those too hardened or too unaware to view the latest representation of suffering in Palestine, or in any of the many other sites of injustice on the earth. The absurd, tragic laughter found in Arna’s Children interrupts this too-easy tragic narrative, and disturbs the viewer’s desire for simple pathos, for a catharsis that allows one to return home feeling chastened but clean, ready to resume life as usual. In place of any comfort, even the comfort afforded by the simple, purging tears of tragedy, the film leaves us shattered. It also presents us with an ethical choice: while it is as far from the didacticism of propaganda as can be imagined, it nevertheless demands from us some response, if only as a way to come to terms with the desolation of its effect. It’s status as a masterpiece, as Yitzhak Laor commented at the time of its release, comes from the fact that “it was made with a trembling hand, with the stammer of someone who does not know whom to mourn most: his mother, the boys from the Jenin camp or the trampled hopes of people yearning to be free."

This is also why the film inspired such resistance among viewers anxious not to have their sense of equilibrium regarding the “conflict” disturbed. Typical of such a reaction was Manohla Dargis’s suggestion, in her review of Arna’s Children in the New York Times in 2004, that “a subject as complex as this demands greater rigor, deeper intelligence and a sense of dialectics. Only someone blind to suffering or blindly partisan could deny that the tragedy of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict plays out on both sides of the divide.” We are back to Adorno: “the distinction between executioners and victims becomes blurred.” We want to be assured that there are victims on both sides; more than that, we want to be assured that there are in fact “sides” in the first place, rather than face the reality of a situation created and sustained by a project of settler colonialism, which has resulted in a single, apartheid state. The demand for “dialectics” here is no more nor less than a demand for comforting obfuscation; Arna’s Children responds with unsparing clarity. Indeed, one wonders, given the fact that the film takes as its focal point an Israeli Jew who spends her life working to cross between the worlds of colonizer and colonized and to highlight its destructive effect on both “sides,” exactly which point of view would need to be represented in order to achieve the “dialectical” approach that Dargis demands.

Viewed today, Arna’s Children also provides a sharp rejoinder to the idiotic suggestions now being made that in the past few months, Palestinians have suddenly “discovered” non-violence as a form of resistance. In fact, what the film helps to document is the fact that for decades, all attempts by Palestinians to resist the violence of the Occupation — even, as in this case, when such resistance takes the form of artistic practice — have been met by increasing levels of violence from Israel. And today, as has also been true for decades, those who make the most noise about the need for “Palestinian Gandhis” remain deafeningly silent when Israeli forces slaughter unarmed Palestinian protesters. The film stands as both document and indictment: anyone who did not speak up when a children’s theater in Jenin was destroyed by bombs and bulldozers has forfeited any moral ground from which to issue exhortations about the preferred form and nature of Palestinian resistance.

Indeed, the film powerfully calls into question the very line between “violent” and “non-violent” resistance, since it reminds us that in a fundamental sense, it is the nature of the violence of the oppressor that determines the forms of resistance enacted by those who must resist this violence. “Non-violence is a piece of theatre,” Arundhati Roy recently told an interviewer, echoing the film’s explicit link between resistance and performance. “You need an audience. What can you do when you have no audience? People have the right to resist annihilation." By the same token, the film also shows that there may be more of a continuum than a contrast between forms of “non-violent” and “violent” resistance. As Elias Khoury suggests in his appreciation of the film, it is too simple to suggest that Arna’s children somehow “abandon” a form of non-violence when they take up arms against the Israeli invasion of Jenin Camp; rather, as Khoury puts it, these young men “found that the meaning they learned in Arna’s theater leads them in their early youth to create the epic of Jenin Refugee Camp, through its heroic resistance in 2002.” As Arna’s wild youth and her equally wild old age are of a piece, so too her children’s theatrical resistance and their armed resistance are of a piece; trying to separate them does nothing but impose a false but smugly comforting distinction between “violence” and “non-violence.”

In the penultimate scene of the film, we are informed of the death of ‘Ala’ only two weeks after the birth of his son, and the camera lingers on an image of father and son. If the film had ended here, we would have been left with what might be seen as a potentially “satisfying” tragic ending. But it ends on a very different note. The camera frames a scene of devastation and rubble, one of many such scenes we have been shown in Jenin Camp. A young boy enters the corner of the frame, followed by others (they are perhaps a few years younger than the children who performed in Arna’s now-ruined theater), a few carrying sticks. They begin to chant, a chant taken up by others, as the camera stands still, watching and listening:

Answer the call from the Aqsa mosque.

Call out against those who oppress us.

For your sake, my steadfast people

Together we will fight and struggle.

Raise your voice and say:

God is great, God is great.

Every mother’s tear and every drop of blood takes its toll.

For every martyr that falls a new one will rise.

For your sake, my steadfast people

Together we will fight and struggle.

Raise your voice and say:

God is great, God is great.

By the time the scene (and the film) ends, the chant has started to fade out of its own accord, and the children have begun to leave the frame, before we go to black.

As with so much in the film, the ending is completely ambiguous, and it is the ambiguity that so effectively disturbs, leaving us without the comfort of meaning. The scene almost seems designed to act as a Rorschach test: those who hold to the racist “Palestinians raise their children to be terrorists” line may think they have found evidence; those who like to cheer on Palestinian resistance from a safe distance may indeed cheer; but neither of these simplistic reactions can take in the full idiosyncracy of the scene. Nor can it be seen as a representation of children mindlessly repeating political slogans at the prodding of their elders. The scene is clearly a scene of children being, among other things, children: there is a good amount of good natured shoving, and attempts to remember the words and keep in time (see in particular the performance of the young bespectacled child in the pink sweatshirt). In other words, the only thing we can say for sure is that we have watched another performance by the young people of Jenin Camp. It raises questions that are left unanswered: for example, was this performance staged? (Intentionally or not, it echoes a scene in Godard’s Ici et ailleurs that features a young girl theatricaly reciting a poem by Mahmoud Darwish in front of the ruins of the city of Karameh, another famous site of Israeli invasion and Palestinian resistance). And then beyond that: is anything that happens in front of a camera, especially a camera being held in the hands of one who has come from outside, not staged in some way? (We recall the scene of Arna’s children slyly playing their roles before the camera of their Israeli interviewers.) No answers are to be found at the end of Arna’s Children, no lessons, and thus no comfort.

Now, however, nearly a decade after that scene was shot, we can say a few things for certain. The film ends with the next generation of Jenin Camp: the son of ‘Ala’, the chanting children. This is the generation that has brought The Freedom Theater to life, that is now acting in its productions and making films of their own. This is also the generation that is now taking part in the new acts of resistance that help to kindle the hope that the Arab Spring may finally encompass a true liberation in Palestine.

And Juliano is gone. That fact remains, and the fact that he has left us this magnificent legacy — not just this film, but the continuing miracle of The Freedom Theater — should leave us absolutely unconsoled. I do not want this review to be an act of consolation, any more than Arna’s Children is an act of consolation. I want to leave you unappeased.

The day of Juliano’s death, I wrote what I thought of as a piece that was part obituary, part tribute. It may be that I was able to write something because I didn’t know him personally; those who knew him best were I think too shattered to speak in those first days, as his friend Udi Aloni later movingly described. Many people responded to the article with great kindness, but I was struck by two criticisms leveled at it. The first complained that I did not specify the details of Juliano’s death, or speculate on who committed the murder. The strong implication was that this was a way of avoiding addressing the fact that Juliano’s killer was very likely Palestinian; had he been shot by the IDF, this criticism went, my piece would have been full of outrage (I thus stood accused of belonging to the uncritical “amen coner”). The second criticism also upbraided me for a lack of outrage, albeit of a different kind: I had originally begun the article with the sentence, “Jadaliyya is tremendously saddened to report the death of Juliano Mer Khamis earlier today,” and this reader demanded to know why I had not used the word “murder” instead of “death.”

I acknowledge that there is something behind both of these criticisms. But I feel, I must admit, a very deep sense of repulsion at what I think lies behind each. The first criticism is more actively objectionable, because I detect in it a rather large dose of schadenfreude. There is something very similar in the tone of a truly awful piece in the Guardian, which opened by suggesting that Juliano “wanted to create an ‘art revolution’ to help liberate the Palestinian people, but only managed to alienate those he most wanted to inspire.” Udi Aloni does a fine job of responding to this disgusting sense of schadenfreude expressed by those who have no real feeling either for Palestinians or for Juliano’s work:

I have great contempt for those journalists who were in such a hurry to rejoice about the fact that he was probably murdered by a Palestinian. Their mantra was “here is this wonderful man, come to help the natives, and they murdered him.” Strange, I do not remember those same journalists rejoicing when a Jew murdered Yitzchak Rabin in the name of the ideology which today rules our country. An ideology served by those same journalists.

But the second complaint, the one demanding that I show the proper sense of outrage at Juliano’s murder rather than simply mourning his death, also leaves me with a disturbing feeling. I don’t like the fervor of it; I don’t trust this sense of outrage. It is the outrage of those who, I suspect, have by now moved on, in order to react to other stories that will give them another reason to vent righteously. I’m increasingly suspicious of outrage; I think we leftists indulge ourselves too often in this feeling, and that it does too little work for us.

Indeed, I think there is something in common between this sense of outrage and the cleansing feeling of enjoyable sorrow that Adorno tried to warn us away from, and that Arna’s Children refuses to indulge. Being outraged makes one feel active, involved, engaged. It’s a false feeling, an easy form of moralizing. It is I think akin to the “spiritual phenomena” that Adorno accuses critics of paying attention to when they should instead be addressing the presence of “despair and measureless misery.” By insisting on this form of spiritual moralizing, Adorno maintains, we are too easily “tempted to forget the unutterable, instead or striving, however impotently, so that humanity may be spared.” [2]

In a very fundamental way, I want to try to attend to the unutterable. What was obvious to me, and remains so, is that Juliano was killed for being a true artist, which means, if one can achieve it, telling no one what they want to hear, and thus making enemies all around. Very few artists achieve the relevance and signifcance needed for this, and it is a tribute to Juliano that working there in Jenin, the site of generations of crimes, he managed to make himself seem dangerous to so many, by helping to reveal the criminals from all sides. “What kind of resistance [to occupation] is the play Animal Farm…?” the Guardian quotes one of his attackers as asking. An entirely appropriate one, we must respond, one that reveals the ease with which solidarity can be traded away for power and a place at the (bargaining) table.

Juliano’s revolution was not the “art revolution” referred to with ill-disguised contempt by hack journalists. It is a revolution, political and aesthetic, against all forms of authoritarianism. In that sense, it has everything in common with the revolutions breaking out throughout the region today. Arna’s Children, the masterpiece with which Juliano honored the wildness of Arna and the children of Jenin Camp, is itself a fitting tribute to Juliano’s own wild revolution. It demands more from its viewers than we have yet been able to summon from ourselves; in its unsparing way, Juliano’s film demands that we find ways of moving beyond tears and sentimentaity, beyond pious outrage, beyond tongue-clicking or cheering, in order to begin to create forms of active solidarity.

[1] Theodor Adorno, “Commitment,” in Aesthetics and Politics (New York: Verso, 1998), p. 189.

[2] Theodor Adorno, “Cultural Criticism and Society,” in Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), p. 19.