[”A Profile from the Archives“ is a series published by Jadaliyya in both Arabic and English in cooperation with the Lebanese newspaper, Assafir. These profiles will feature iconic figures who left indelible marks in the politics and culture of the Middle East and North Africa. This profile was originally published in Arabic and was translated by Mazen Hakeem.]

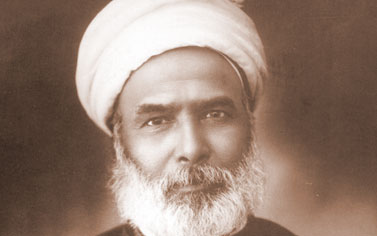

Name: Muhammad Abduh son of Hussein Khair-Allah

Date of Birth: 1849

Place of Birth: Born to a prominent rural family in the village of Mahellet Nasr, Beheira Governorate, in the Nile Delta region of Upper Egypt, during a time when farmers suffered from heavy taxes and unjust laws imposed upon them by the government.

Profession: A pioneer of the Islamic renaissance and the school of reform and renewal.

Muhammad Abduh

- Muhammad Abduh`s renewal tendencies began to emerge at an early stage in his educational career. He left Al-Ahmadi Mosque in Tanta one year after joining it despite the fact that this mosque was a reputable institution in religious education following Al-Azhar. Abduh refused the existing teaching method at the mosque which relied heavily on memorizing more than thinking. However, due to pressure from his uncle, who was of great influence on him, he went back to Al-Ahmadi Mosque.

- Started his study at Al-Azhar in 1866 and spent three years there. During that time, there were two parties at Al-Azhar--the doctrinally conservative and the Sufi. He showed a tendency towards Sheikh Darwish Khidr, his father’s uncle, a Sufi affiliated with the Senussi movement in Tripoli, Libya.

- In 1872, he met Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani whom he accompanied and later on became his best and closest student. He used to publish in his name, Amali al-Afghani, and present the lessons that he attended at al-Afghani’s house to audiences in Al-Azhar. This companionship had the biggest effect on Abduh’s political and religious views. It caused Abduh, along with the political and religious effects from al-Afghani, many problems in his career:

- After being appointed as a history teacher in Dar al-`ulum (House of Science) School in 1879, he was discharged and confined to living in his village in the same year that al-Afghani was banished from Egypt.

- In 1880, Riadh Pasha (the head principal) managed to get him a pardon. He sent for Abduh and appointed him as editor in Al-waqai’ al-masriah (Egyptian Facts), an official state newspaper. He later became editor-in-chief and was responsible for monitoring publications.

- Kept away from teaching and worked in journalism and politics. His writings became a platform for his views on religious renewal and political opinions during all stages of the `Urabi Revolution against British occupation. He was arrested, imprisoned, and sentenced for exile for three years. He left for Beirut in 1882.

- Lived in Beirut for one year. Then, he followed his teacher al-Afghani to Paris in late 1883. Together, they issued Al-`orwah al-wuthqa (The Most Trustworthy Handhold).

- After the cessation of Al-‘orwah al-wuthqa, he went back to Beirut and taught at schools there for three years. He returned to Egypt in 1888 after the Khedive gave him permission to settle there. He was appointed as a judge in religious courts.

- In 1895, he convinced the Khedive to establish an administrative council for Al-Azhar. He remained one of its most prominent members for ten years and was able to achieve some reforms through it.

- In 1899, he was appointed Mufti for Egypt (i.e. the highest religious authority in the country). He managed to reform religious courts and endowments. His fatwas (religious legal opinions) aided him in interpreting Sharia in accordance with modern needs.

- Died in 1905.

Methodology and Ideas

- Muhammad Abduh rejected the traditional method that dominated in religious studies. He declared his resentment for traditional Muslim scholars and was amazed by the ignorance of those whom he described as “transcribers” and how they forbid dealing in sciences which he called “true sciences,” referring to other modern and contemporary sciences. Abduh expressed this rejection in his book Letter of the Conceivables (risalet al-waredat) published in 1874. He also published an article entitled Islam and Christianity Between Science and Civility (al-islam wal nusraniya bain al-`ilm wa al-madaniah), in which he explained his conviction that Islam encourages modern scientific methods.

- His mentor, Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, was the man with who had the greatest effect on his life. As an obeisance and an homage to the relationship he had with al-Afghani, he described him in Letter of the Conceivables as the perfect wise man and the true right. It is said that al-Afghani transferred Abduh from hermitage Sufism to philosophical Sufism and opened him up to journalism, religious reform, and politics. He joined him in the political organizations that he formed. In fact, he went to work in journalism as a result of al-Afghani’s encouragement long before he completed his studies at Al-Azhar.

- Enveloped by an elite cadre of intellectuals who represented the Egyptian, Arab, and Islamic schools of thought, most saw liberalization and development as the fruit of education and enlightenment. This school holds hope in the selected intellectual elite rather than public movements and popular trends.

- Befriended and corresponded with many orientalists and foreigners including: Gustave Le Bon, Herbert Spencer, Leon Tolstoy, and Alfred Blunt.

- Rashid Rida took it upon himself to present and publish Abduh`s ideas and writings in his magazine Al-Manar. This occurred during the late years of Abduh`s life and continued after his death. Rashid Rida`s readings of Abduh are the primary source and reference for academic and non-academic studies of Muhammad Abduh as one of the great pioneers of the Islamic reform movement.

- Many researchers of Abduh`s history and ideas have drawn attention to the care that should be taken to avoid fully depending on Rashid Rida’s reading of Muhammad Abduh. They suggest the adoption of a modern strategic reading which takes into consideration the circumstances in which these reference were framed.

- Muhammad Abduh and his mentor al-Afghani drew the attention of many intellectuals. His complete works were published in Beirut by The Arab Institution (al-mo’asasah al-a’rabiah) in the early seventies and were verified by Dr. Muhammed A’marah.

- Mohammed Haddad presented another reading of Abduh in his book Muhammad Abduh: A Modern Reading in the Religious Reform Narrative (qira’a fi khitab al-islah al-deeni), published by Dar Al-Tali’ah in Beirut, 2003.

![[Public intellectual Muhammad Abduh]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/abduh_shot.jpg)