While working as a Project Manager at the Fenway Community Development Corporation (CDC) in Boston and as a Consultant to Phipps Houses in New York City, I experienced firsthand how nonprofit developers can contribute to preserving housing affordability in central locations. Fenway CDC builds and preserves housing and champions local projects that engage the entire Fenway community in protecting the neighborhood’s economic and racial diversity. It has operated since 1973 and has developed nearly six hundred homes, housing approximately 1,500 low and moderate-income[1] residents, including those with special needs. In addition, Fenway CDC has supported residents through offering job placement and career advancement services, building playgrounds, running after-school programs for teens and operating a center for seniors. Similarly, Phipps Houses develops, owns and manages housing in New York City. Since its founding in 1905, it has developed more than six thousand apartments for low- and moderate-income families, valued at over one billion US dollars. Phipps Houses manages a housing portfolio of nearly ten thousand apartments throughout New York City. In addition, it serves over eleven thousand children, teens, and adults annually through educational, work readiness, and family support programs.

Now that I am working in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as an affordable housing consultant for several public and private entities, I often wonder: Could private nonprofit housing developers, like the Fenway CDC and Phipps Houses, make an impactful contribution to bridging the supply and demand gap in affordable housing in the GCC for both citizens and non-citizens? Could the experience of other countries with nonprofit housing developers be distilled and adapted to the GCC states?

To answer these questions, I will first discuss the main attributes of nonprofit housing developers, followed by a discussion on the shortage of affordable housing for citizens and non-citizens in the GCC and the resulting need for nonprofit housing developers. I will then recommend strategies to enable the growth of nonprofit housing developers and end with a few concluding remarks.

Nonprofits Housing Developers as Mission Entrepreneurial Entities

In its 2010 landmark study Mission Entrepreneurial Entities: Essential Actors in Affordable Housing Delivery, the Affordable Housing Institute (AHI) defined Mission Entrepreneurial Entities (MEEs) as "private nongovernment entities that are in the business of making housing ecosystemic change by doing actual transactions valuable in themselves that also serve as pilots and proof of concept.” MEEs could be Non-Governmental Organizations, Community Development Corporations, or Housing Associations, labels that have sometimes been used interchangeably. The study profiles twenty-three MEEs in the United Kingdom and the United States, where, in both countries, there has been a steady migration from entirely publicly managed and operated systems to hybrid public-private models, with MEEs as key delivery mechanisms.

According to the study, the three main attributes of MEEs are: (1) being mission oriented, since their goal is impact, not just profits; (2) entrepreneurship, taking risks and persuading established institutions, including governments, to approve proposals, provide capital, etc.; and (3) self-containment, because sustainable MEEs must make profits and maintain a positive cash flow. However, generated profits are used to further the purposes of the organizations instead of being distributed to managers and shareholders.

MEEs also share the following strengths:

- Willingness to serve populations that the private for-profit sector cannot or will not serve, including the hardest-to-house residents;

- Commitment to providing affordable housing to lower income people for the long term;

- Building strong connections with residents and the communities they serve;

- Commitment to providing various social services that lower income or special needs residents may require;

- Potential for accessing affordable land, buildings and funding through governments and philanthropic entities or individuals;

- Commitment to seeing projects through both during their early and post-delivery phases.

Given the potential of MEEs to serve populations that are not served by private or public housing provision, this essay discusses the potential relevance of this model to the GCC countries. This interrogation is critical at a time during when many GCC countries are facing a shortage of housing for low- and moderate income households. It is also a time in which we are witnessing the emergence of institutionalized charitable giving that could be in part harnessed to help with housing provision. These conditions are creating a ripe environment for the growth of nonprofit housing developers, with the much needed support of the public and private sectors.

Although the types of nonprofit housing developers that may develop in GCC countries will likely be quite different from the ones operating in the United States and the United Kingdom and will depend on the judicial, governmental, economic, cultural, and social stock of each country, the challenges faced by nonprofit housing developers, wherever they are, are likely to be similar: how they act as entrepreneurs, how they activate resources, how they stimulate change, and how they struggle for viability, successful business models, and a solid organizational grip.

The Shortage of Housing for Citizens

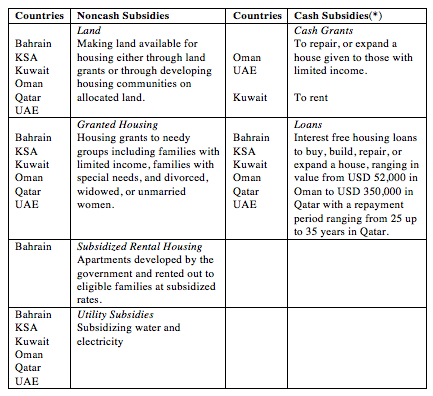

All GCC governments dominate the delivery of housing for citizens through a combination of non-cash (land, completed housing units, and utility subsidies) and cash housing subsidies (grants and interest-free loans), as outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Government Cash and Non-cash Tools to Support Housing for Citizens

[Source: Government Housing Authorities (2014)]

(*)GCC governments probably give cash subsidies to citizens with limited income to repair or expand a house.

The countries listed here have a more formal and publicized method of doing so.

However, most housing authorities in the GCC states are unable to meet the increased demand for housing services associated with local population growth due to a combination of the following challenges:

- Lack of coordination between different government entities;

- Lack of clear housing eligibility and priority rules;

- Budget constraints;

- Limited supply because authorities are largely acting as the sole developers;

- High cost of projects because value engineering tends to be absent from many government project reviews;

- Limited legal action against defaulters, which increases the effective subsidy cost of housing.

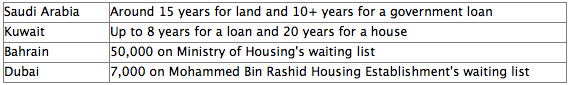

This has resulted in extensive waiting lists for government housing services, as shown in Table 2. Naturally, low- to moderate-incomes families have been the most impacted by the delays.

Table 2: Waiting Period/Lists for Government Housing Services

[Source: Government Housing Authorities (2014)]

Most GCC governments are actively seeking to address the shortage in housing for citizens through a number of measures, including:

- Setting up new champions of housing, such as the recently established Ministry of Housing in Saudi Arabia and the Abu Dhabi Housing Authority;

- Reforming existing policies;

- Increasing governments’ production of housing`

- Exploring Public Private Partnership (PPPs).

The Shortage of Housing for Noncitizens

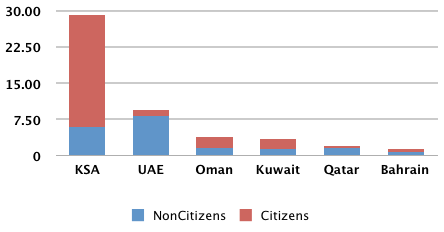

Unlike institutionalized efforts to improve housing for GCC citizens, housing for noncitizens is largely left to the private sector. Although further research is needed to accurately quantify and specify the shortage of housing for low- and moderate-income[2] noncitizens, newspapers and periodical reports by property consultants provide anecdotal evidence that suggest that there is a shortage in housing for low- and moderate- income noncitizens across all major GCC cities. Naturally, the scale of the shortage of housing for low- and moderate- income noncitizens varies according to the percentage of noncitizens in each GCC country, with bigger shortages in countries with more noncitizens, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Citizens and Noncitizens in GCC Countries (2013, in millions)

[Source: The World Population Review (2013)]

Private developers have not been supplying enough housing for low- and moderate- income noncitizens in many cities including the GCC region for many reasons outlined by Jones Land LaSalle in Why Affordable Housing Matters, including:

- Lack of access to affordable land;

- High cost of infrastructure required for housing expansion;

- High cost of providing public transport networks to housing in remote locations where land is typically cheaper;

- Immature mortgage markets which limit access to housing finance;

- Regulatory barriers to new building techniques, therefore restricting economies of scale;

- Low financial returns on affordable housing development compared to the profits investors could reap from developing upmarket residential units.

However, the economic growth of GCC countries is dependent on the sustainable influx of moderate- and low- income noncitizens, whose quality of life and productivity is, in turn, dependent on the availability of affordable housing.

The UAE government may be the most active in the GCC region in addressing the shortage of housing for noncitizens, although further research is needed to assess the impact of its initiatives. Since 2011, Dubai`s Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA) has been regularly producing and updating a Rental Index to achieve transparency, ensure that rents in various Dubai areas are in line with the rental index, and cap rental increases based on the index. In Abu Dhabi[3], the Urban Planning Council (UPC) adopted in 2010 the Middle Income Rental Housing Policy, which requires twenty percent of the residential gross floor area (GFA) in multi-unit residential buildings within developer-led planned housing developments to be developed and managed as middle income rental housing. Furthermore, since Dubai`s real estate sector rebounded in 2013, authorities have introduced a string of measures to cool down the market. For example, the Dubai government doubled transaction fees on real estate sales, while the federal government imposed lending caps for banks, both aimed at putting a halt to "flipping," or the quick resale of a property.

The Need for Nonprofit Housing Developers in the GCC

While the above-mentioned initiatives are important, encouraging nonprofit developers would introduce new key players to the housing market. Nonprofit housing developers could contribute to bridging the supply demand gap, particularly for the lowest income groups, whose need for good quality affordable housing is unlikely to be adequately met by private developers even with government incentives, given their profit considerations.

Some charity organizations already provide housing related services to citizens of various GCC countries with funding from sole benefactors, government sources, zakat collections, donations and returns on investments as detailed in Table 3. Although further research is needed to obtain accurate data, most of the government officials that the Affordable Housing Institute has spoken to agree that the role of charitable organizations in developing and operating housing remains very limited.

Table 3: Examples of Providers of Charitable Housing for GCC Citizens.jpg)

[Source: Affordable Housing Institute (2014)]

Public and private entities could encourage existing charitable organizations offering housing services to do more, while supporting the growth of new and sustainable ones. Such growth would expand consumer choice both for citizens and noncitizens, reduce housing authorities` waiting lists by redirecting the lowest income and special needs households to nonprofit housing developers.

Strategies to Enable the Growth of Private Nonprofit Developers in the GCC countries

While each GCC country has its specific set of challenges and opportunities, below are some overarching suggestions for creating an enabling environment for the growth of new nonprofit housing developers targeting low- and moderate- income citizens and noncitizens. These recommendations also aim to encourage more charitable organizations to go into housing provision as a platform to improve the well being of families, a pursuit which aligns with their missions, objectives, and/or religious obligations.

Provide financing to nonprofit developers: Since current loan and subsidy markets in the GCC states do not have products that cater to the needs of nonprofit developers, governments or philanthropic entities could provide partial development loans, grants or investments to nonprofit housing developers in exchange for long-term affordability. Developers could be required to seek the remainder in the form of loans from private banks, or to fund these costs themselves using donations or reserves.

Concurrently, the goal of nonprofit housing developers must be to become operationally self-sustaining, that is, to be able to meet year-on-year operating needs through earned income alone instead of contributions and grants, whether public or private, the amount of which may change from year to year. This could be achieved through relying on three primary sources: (1) rental income from properties owned or under management, (2) fees from property management responsibilities, and (3) developer fees from an ongoing pipeline of projects. For long-term sustainability, rental income and property management fees are probably more important than developer fees in that they are recurring income streams.

Guide philanthropy: Philanthropy is deeply rooted in the GCC culture, possibly inspired by the religion of Islam, in which all Muslims are responsible for helping the disadvantaged members of society through different forms of giving including zakat, sadaqa, and waqf [4]. Indeed, according to The Global Islamic Finance Report 2012, the GCC region contributed approximately fifteen to twenty billion US dollars every year to the philanthropic sector, which is about 1.5 to 2 percent of GDP.

As charity becomes more institutionalized with a growing number of companies engaged in corporate philanthropy, or corporate charity (zakat), through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives, governments could guide corporations toward high priority sectors, including housing (as is common in Brunei[5]) and incentivize corporations to engage with nonprofit housing developers. This will ensure precious funds are used wisely and properly, aligning the development strategies of the public, private and philanthropic sectors.

Moreover, governments could leverage the religious endowment (waqf) institution, through which land and property are donated, to increase the supply of housing for low- and moderate income households and provide a sustainable property management structure. But both Islamic law and Western experience in land trusts and land leases show that good stewardship can be tailored to waqf type legal and financial structures.

Target noncitizens: As shown in Table 3 above, existing charitable institutions provide housing to GCC citizens only. However, given the crucial economic role of non-citizens, governments could encourage/require nonprofit housing developers to provide housing for low- to moderate-income noncitizens with the financial support of governments and local or international philanthropists.

Regulate nonprofit developers: Housing authorities have to ensure that the stock of rental housing for low- and moderate-income tenants is maintained in a physically and financially sound manner, is administered in a way that best serves the needs of the low-income households, and remains available to lower-income tenants.

Connect nonprofit and for profit developers: Housing authorities could connect private developers and nonprofit developers who may purchase units from private developers and rent them to the lower income households. Such an approach would encourage mixed income communities and create "hybrid value chains"[6] by forging new connections between the public, private and the nonprofit sectors.

Encourage civil society: In nearly all of the GCC countries, civil society legislation restricts the full participation of citizens and residents in the development of their communities, in addition to the prevalent dependence of citizens on the governments to meet their needs. Thus, a more favorable environment is needed to build a strong and influential civil society from which nonprofit housing developers will grow.

Conclusion

Nonprofit housing developers are the missing link between residents, governments and private developers. However, growing successful nonprofit housing developers takes time and involves many trials and errors both on the policy and organizational levels. Much of the information included in this article is based on research done by AHI on nonprofit housing developers in the United States and the United Kingdom. Naturally, more research needs to be done to understand the work of the existing charity organizations that provide housing and opportunities in various GCC cities. Nevertheless, AHI believes that the emergence of a few nonprofit housing developers is a watershed event for any nation`s affordable housing ecosystem. Until they emerge, policy makers and private sector actors will have difficulty meeting the housing needs of the most deserving households.

------------------------------------------------

[1] Both Fenway CDC and Phipps Houses determine income eligibility using specific government procedures.

[2] To my knowledge, GCC countries do not have official definitions of "moderate and low income households". Therefore, I am following the US Census Bureau in defining moderate income as earning eighty percent of the median family income for a given metropolitan area, and low income as earning fifty percent of that figure.

[3] In Abu Dhabi, rental caps were removed in Q4 2013. A property rental index may be launched later this year.

[4] Zakat is obligatory charitable giving by Muslims calculated as a percentage of wealth above a certain point. Sadaqa is voluntary charity by Muslims. Waqf is an Islamic endowment of property to be held in a trust and used for charitable or religious purpose.

[5] The Brunei Islamic Religious Council collects obligatory zakat funds and redistributes them the poor through a number of welfare services, including food, job training, and housing. The council collects zakat through mosques, banks offering automatic zakat payment services, and obligatory corporate zakat. In 2009, the total zakat collection amounted to ninety million BND ($61.79 million), thirty-five million BND of which were allocated for housing purpose, including cash grants for homebuilding or renovation and government loan repayment assistance.

[6] The Ashoka Foundation coined the term.