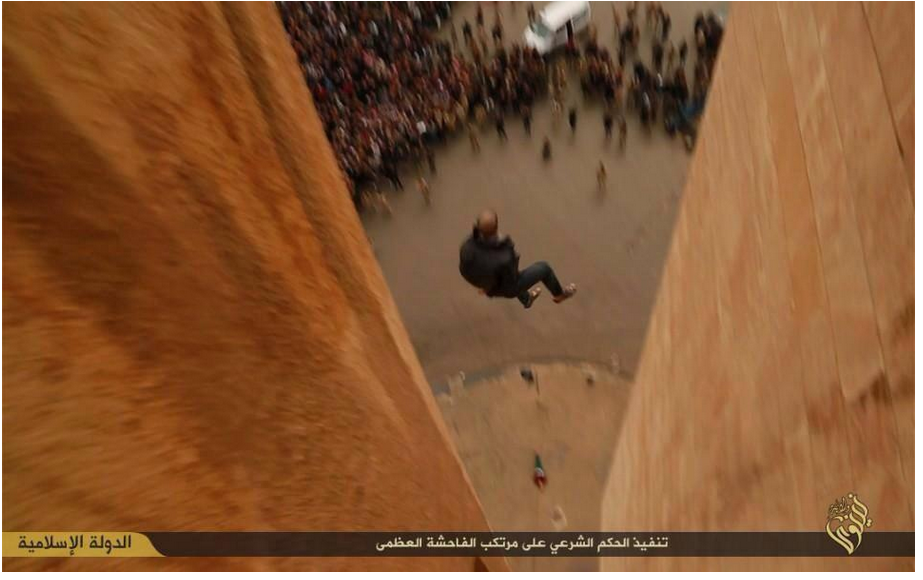

Hands shove them forward, bound and blindfolded. Then comes the step when the stone beneath them stops and nothing is there. The photographs appall but they have the solidity of things you can see; they suggest but cannot summon the feel of one terrifying lurch in darkness when all that is solid falls away. Death is what happens when you are there, alone, and the world disappears.

ISIS stands for the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, which now styles itself just the Islamic State. Many Arabs prefer to call it Da’ish, an acronym (Ad-Dawlah al-Islamiyah fi al-‘Iraq wash-Sham) that the militants despise, partly because it echoes Arabic words for bearers of brutality and discord. Even in Iraq, where death dominates life, Da’ish’s violence is exceptionally uncompromising and public. An Egyptian leftist friend of mine calls it unprecedented. Plenty of political movements employ sadism (Stalin, Hitler). Some embrace it ecstatically (Romanian Iron Guardists smeared themselves with their victims’ blood and chanted, “Long live death”). But Da’ish treats absolute violence as propaganda, as entertainment.

Displaying violence has become Da’ish’s essence, as if its ideology were a snuff film. Although it is commonplace to say violence wants to terrify (to shock and awe), the effect is to make unrestrained violence, which Hannah Arendt saw as the opposite of political life, the main feature of the public world. Da’ish’s broadcast deeds become as commonplace as campaign speeches. Western audiences, astonished at first, are now inured. The pictures keep coming, but only a few hit their target. Like these.

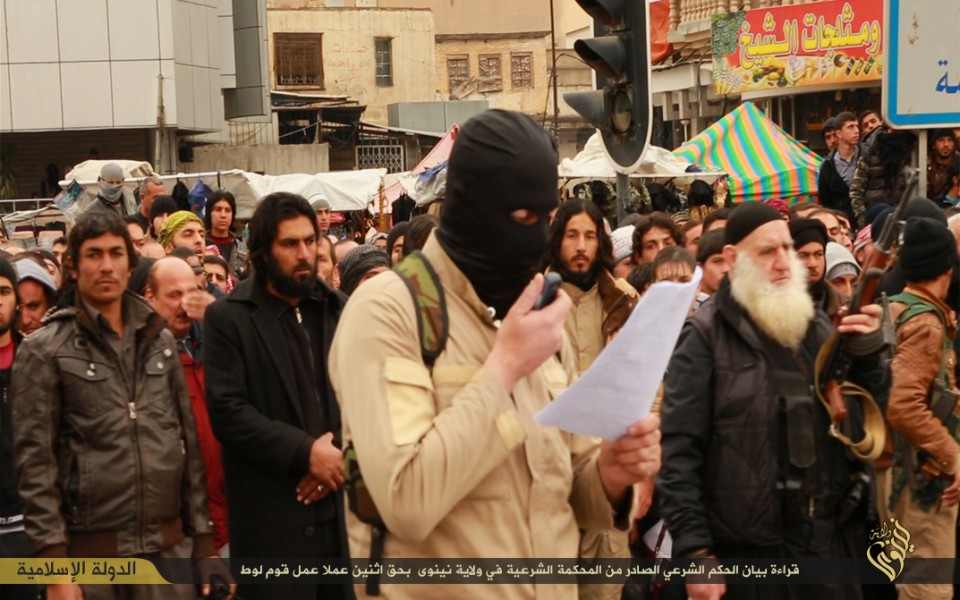

What do we know? According to Twitter, these pictures first appeared on 15 January 2015, on the media-sharing site Justpaste.it (the post has since come down). They spread immediately. The left side of each photo reads “Islamic State”; the right, “Ninawa” (Nineveh is Iraq’s northernmost province). Presumably they came from the Islamic State’s provincial media office.

.jpg)

[Caption: "Muslims gather to watch the application of the verdict."]

[Caption: "The shari’a verdict for banditry is stated in an introductory sign."]

The sign in the above photo reads:

The Islamic State / The Caliphate in the Footsteps of the Prophet / Islamic Court – Nineveh State

Allah the Almighty said, “The penalty for those who fight God and his Prophet and spread corruption on earth is to be killed or crucified, or their hands or legs to be amputated, or to be exiled from earth. They deserve disgrace in mortal life and great torture in the afterlife.”

Verdict: Crucifixion or death

The reason: Kidnapping Muslims and stealing their money by force and in the name of the Islamic State.

[Caption; "Reading the statement of the shari’a verdict issued by the shari’a court in the province of Nineveh against two persons who practiced the deeds of the people of Lot.” (“People of Lot” derives from the Qu’ranic version of the Sodom story; “sodomite” might be the English translation.)]

Then back to the tower’s top again. First a man in a red sweater is hauled forward.

[Caption: "Applying the verdict on one who practiced the deeds of the people of Lot, by throwing him from a high place."]

Then a man in a black jacket is taken to the top of the tower; the caption is the same as the one above. The next image is of him being thrown off the tower.

[Caption: "Applying the shari’a verdict on the person who committed the greatest crime."]

[Caption: "This is the penalty for those who encroach upon the limits Allah the Almighty set."]

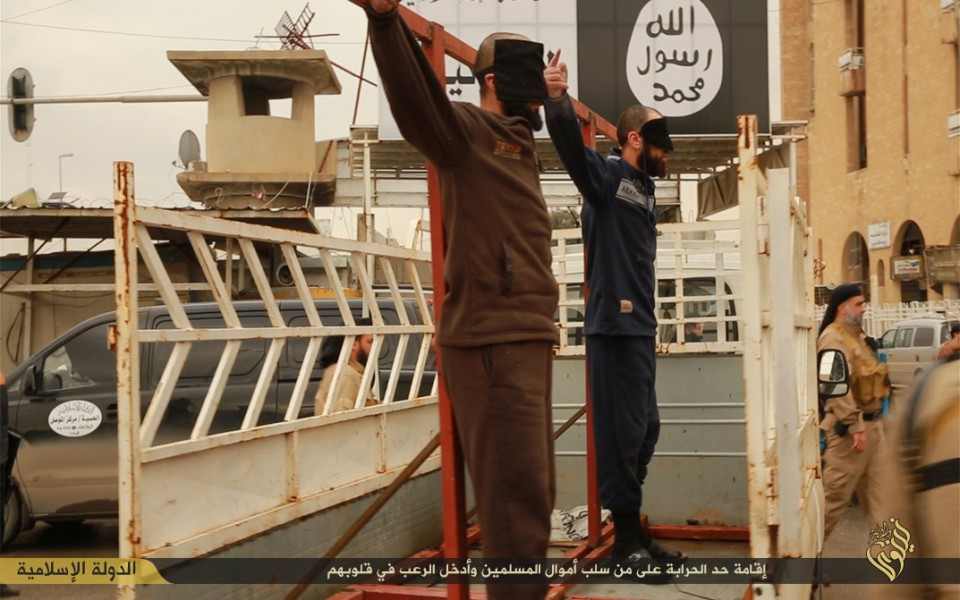

Back to the Square

The frames on which men crucified hang are faintly visible in the first photo. In the second photo, they are clear.

[Reading the statement of the shari’a verdict issued by the shari’a court in the province of Nineveh against those who robbed Muslims using the force of weapons.]

[Caption: "Applying the penalty for banditry on those who stole the money of Muslims and instilled terror in their hearts."]

The bandits are shot in the head.

[Caption: "This is the punishment for what their hands did."]

[Caption: “Let them be an example to those who feel tempted to assault Muslims in the Caliphate state.”]

The last two photographs are in a park.

[Caption: “Reading the statement of the shari’a verdict issued by the shari’a court in the province of Nineveh against a woman who committed adultery.”]

The woman is stoned to death.

[Caption: “Applying the penalty as an expiation of guilt.”]

Beyond those bare descriptions, all is speculation.

The executions may have happened on 14 January, maybe earlier. The city is probably Mosul, capital of Nineveh province, which Da’ish captured last June. The white-bearded man who lurks in several shots and supervises the stoning, looking like a vengeful garden gnome, is likely Abu Asaad al-Ansari, a well-known ISIS cleric. The death tower is tall, yellow, mostly windowless. It may be the Tameen (Insurance) Building, a 1960s relic turned at some point into government offices.

The story went viral internationally because of the two “sodomites” thrown to their deaths. The executions of the bandits and the adulteress were inadequate to colonize attention. Yet those victims are, in the images, the most anonymous: merely bent backs, or faceless corpses. It is worthwhile, then, to pause and ask what we have seen. What do we recognize in the victims? And what do we understand about the perpetrators?

The first looks easy. Jamie Kirchick (an instant expert on Islam and other un-American things) wrote, “As a gay man, I thought, there but for the grace of Allah go I.” They are gay; they are like us. The facelessness actually facilitates emotion; in the absence of particular selves to see, a generalized identity sets in.

It is good to feel that identification. Only extraterrestrials and lice embrace all humanity without exception; most of us look for specific commonalities to carry sympathy across the abstract gulfs of difference. Still, sympathy always simplifies, smoothing over alienating idiosyncrasies, bland as asphalt. It leaves things out.

Back in 2012, there was a surge of killings of “effeminate”-looking men in Baghdad. Western gay activists immediately called these “gay” killings. In fact, as I quickly found, that was not true. Iraq’s Ministry of Interior and the media had been inciting fears of “emos,” youth corrupted by Western styles and music and gender ambiguity. Militias, mostly Shi’ite, took up the cause, murdering dozens or hundreds of suspect young men. Certainly gay and transgender people were caught in the sweeps. The rhetoric was vague enough to vilify any men who did not look masculine enough, and some Iraqi queers had found an emo identity congenial. But “gay” on its own was the wrong rubric to explain what was going on.

When I said that publicly, one well-known American gay blogger wrote that I was “confusing.”

You can’t just write a blog post about violence in Iraq, especially on a gay blog, nobody cares about violence in Iraq in general—and if anything, they’ll probably shrug and say “90 deaths sounds like a typical day in Iraq, oh well.” Unless it’s violence against someone we care about—then we care. The gay angle works … I’m just not sure how we write a post saying lots of people are getting killed, stop it, with any authority, or in a way that moves people.

On one level, perhaps, he was saying I want blog hits, and I won’t get them if I can’t write about gay stuff. On a larger level, though, he was right, and even principled: You cannot make people care unless, well, there are people they care about. The gays are an organized constituency primed for caring. There is no comparable global solidarity among bandits or adulterers. (There is, of course, an international women’s movement that combats stonings and other atrocities, but it is stretched pretty thin.) Yet this was an American blogger, writing for Americans, in the nation that destroyed Iraq. Surely that is an angle. Could you drum up a little compassion, or even penitence, for what your readers’ government did to another country? Maybe they cannot fix it, but they could stop their government from doing it again. The strange thing is that, even though his blog has a big American flag on the masthead, gay as a source of sympathy trumps American as a reminder of responsibility. Probably that is because sympathy, unlike responsibility, does not carry obligations.

[US patrol in Fallujah, 2004. Photo by Anja Niedringhaus, AP]

This image did not go viral.

Context Gets Erased on Both Sides

The American gays can wield “gay” to forget they are also American, at least in any way that implies guilt. But calling the victims “gay” and stopping with that erases the wider fears about masculinity and cultural invasion that inform the violence—obliterating what links the dead to the politics of post-occupation Iraq, and to the countless other Iraqis exiled, or injured, or killed.

Moreover, what do we mean by “gay”? It is not self-evident. The International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC) at first stuck the “gay” label on the 2012 killings; they retracted it rapidly, to their credit. Now they have issued a warning about the latest Mosul murders. They caution

in the strongest possible terms against assuming that the men identified as “gay” would have self-identified that way, and against assuming the men engaged in homosexual acts. If the men did not identify as gay, the allegation is inaccurate and obscures the Islamic State’s motivation for publicly labeling them as such. If the men indeed identified as gay, widespread publicity potentially exposes their families, loved ones, and intimate partners to harm.

They are right on the dangers, wrong on the rest. The Islamic State did not “publicly label” the men “gay.” It said they “practiced the deeds of the people of Lot.” In the Qu’ran, the prophet Lot preached against the things the residents of Sodom did—deeds often called liwat in Arabic, from his name; “sodomy” is a partial English equivalent. Da’ish killed the men for committing an act, not for inheriting a description. The difference matters. The American sympathy the blogger invoked demands its beneficiaries be like us, not just behave like us in bed. But Da’ish does not posit a fixed, communal form of selfhood derived from “liwat.” The category “gay” means nothing to it. Sex exists for Da’ish in religious and juridical terms, as deeds, not identities.

[Lot’s people feel the fire and brimstone, in a scene from an Arabic cartoon version of the story.]

The idea that, deep down, Da’ish must see sex as we do is put to political purpose. Polemicist Jamie Kirchick assimilates the Mosul killings conveniently to the Paris attacks in December.

A thread links these atrocities to this month’s murder of four Jews at a kosher supermarket in Paris, beyond the fact that the culprits in both cases are Islamist fanatics…The more salient commonality pertains to the victims, executed solely because of irrevocable traits: Jewishness and homosexuality….In Iraq, no expression is necessary as cause for atrocity. Gay men are hunted down and killed like rats solely owing to the fact that they are gay.

Kirchick clearly knows little about Iraq and less about Da’ish. Da’ish pursues the practitioners of liwat not to eliminate a race, but to discourage what it imagines are preventable perversions. Gay men have been hunted down in Iraq not “solely owing to the fact that they are gay,” but because a general environment where masculinity is believed under threat, and cultural authenticity endangered, makes specific behaviors—the way you dress or walk, where you meet your friends, whether and how you are penetrated—suspect or criminal. It is exactly these “expressions,” not the identities we impute from thousands of miles away that put victims at risk. Da’ish is deluded, the Iraqi moral panics are paranoiac, but ignoring the context and motives behind the violence makes it impossible to help stop it.

[Video memorial for Saif Raad Asmar Abboudi, a twenty-year-old beaten to death with concrete blocks in Sadr City, Baghdad on 17 February 2012.]

For Kirchick, though, the idea that Muslims see gays as one unchangeable collective opens the door to treating Muslims the same way. It is us versus them. “Oppression and murder predicated solely upon their victims’ identities,” he writes, “provides [sic] ultimate clarity about the nature and intentions of radical Islam.” What this clarity is, he does not say, but you get an idea from how he describes the scene: “A crowd below [the tower] gawks like spectators at a sporting event.” Check those photos: who is gawking, or cheering the killers on? The audience looks tense, unwilling.

Mosul is a religiously and ethnically diverse city, which Da’ish conquered last summer. The militia may force the occupied population to attend executions, but it cannot compel enthusiasm. Yet Kirchick’s own prejudices steamroller Da’ish and those it oppresses into the same ersatz category: the enemies of gays. This is a clash of civilizations, in which the “irrevocable” identity of one side mirrors the monolithic irrevocability of the other. (And Kirchick’s insistence that killing gays is worse because they have “identities”—as opposed to robbers, adulterers, women—echoes Da’ish’s own deranged value system, where stealing “the money of Muslims” merits a higher penalty than simple theft.)

Killing “gays” evokes an intense response in our societies partly because there is a prefabricated constituency that answers. Yet this intensity also helps obliterate our ability to perceive the actual context of Iraq, not just its multiplicity and complexity but its past. To see Iraq clearly is to see not us-versus-them but us-and-them, not just an opposition but an entanglement, the violence woven into a history with the barbarities that the US and its coalition caused. Instead, it is versus that infuses the British Daily Mail‘s blaring version of the murders: “While the world reacts with horror to terror in Europe, new ISIS executions show the medieval brutality jihadists would bring to the West.” You see? It is just about us, after all, because they’re coming, they’re bringing their business here; all those page-one warnings about immigration were spot on. First ISIS takes Baghdad, then Bethnal Green. What happens on the Tigris does not matter in itself. What counts is keeping a crazed Tower Hamlets mob from tossing Soho’s gentle denizens off the London Eye.

[Front page headlines in the Daily Mail.]

This leads to the second question: How do we perceive the perpetrators? Violence based on sexuality has been a minor theme drumming through US and British reportage on Iraq ever since the 2003 invasion. (It has tended to drown out violence based on gender, though the two are certainly related.) But how seriously it is taken has depended, at every point, on the politics of the invading powers.

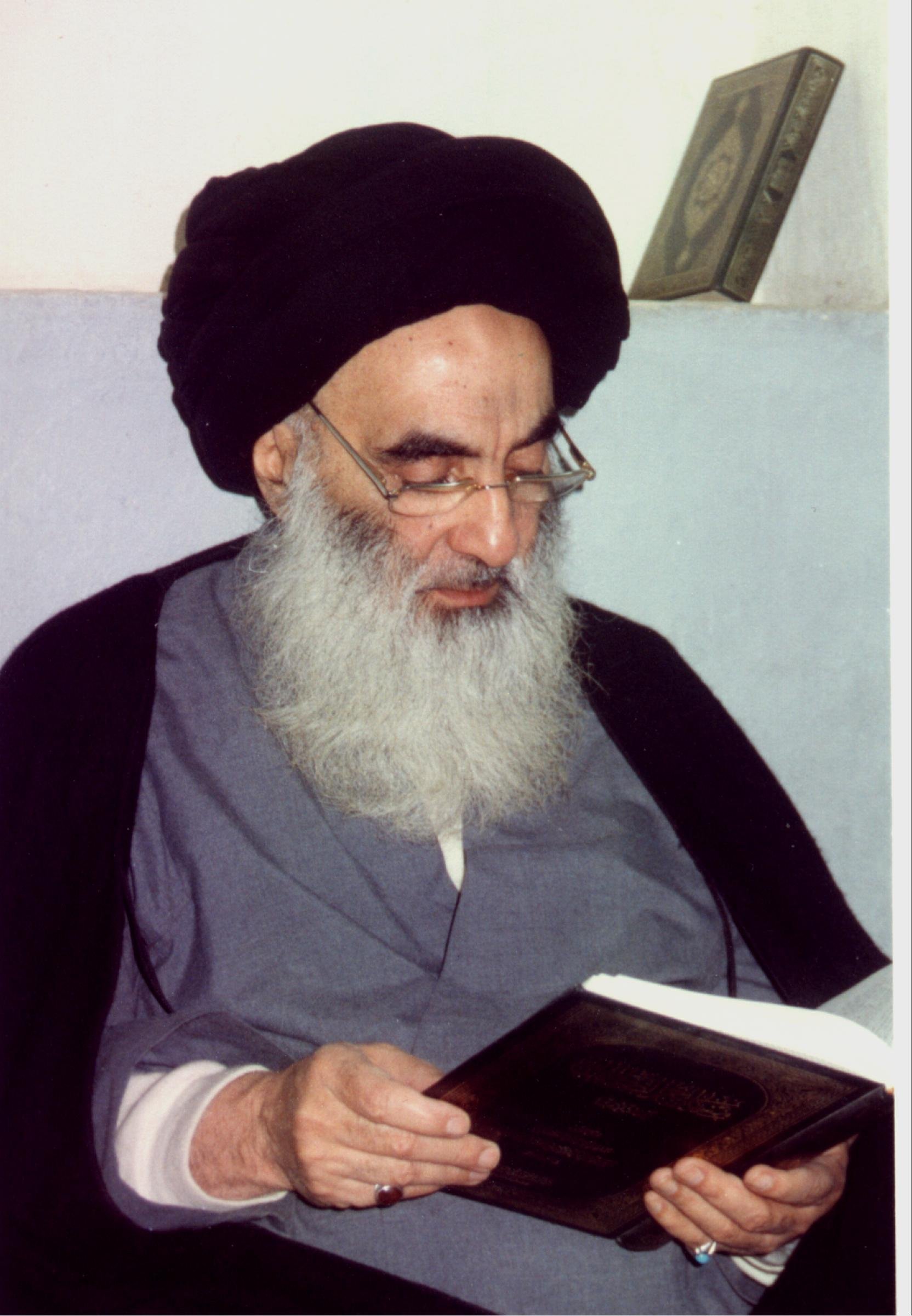

ACT ONE: Sporadic reports of LGBT people targeted for violence started emerging not long after the invasion. Ali Hili, an Iraqi exile in London, was a key source. Hili had a wide network inside Iraq; he was also corrupt and unreliable. He placed full blame for the killings on Grand Ayatollah al-Sayyid ‘Ali al-Husayni al-Sistani, the spiritual leader of many Iraqi Shi’ites—and on the Badr Brigade, a militia affiliated with Sistani. Peter Tatchell and reporter Doug Ireland both promoted HIli’s checkered career and adopted his version. The “campaign of terror is sanctioned, some say orchestrated, by Iraq’s leading Shia cleric, Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani,” Tatchell wrote. “The Badr Corps,” Ireland intoned, “is committed to the ‘sexual cleansing’ of Iraq.”

[Grand Ayatollah Sistani.]

There was little truth to these particular charges. When I researched inside Iraq for Human Rights Watch in 2009, I found no evidence that the Badr Brigade had been responsible for extensive attacks on LGBT people; other Shi’ite militias had taken the lead. (Sistani’s website, probably largely written by junior clerics, had once carried a fatwa calling for the death penalty for “sodomy,” but when it attracted attention he quickly took it down.) Politics, tinged with old grudges, propelled the claims. Hili was a former Ba’athist, who shared the party’s loathing of Sistani. Moreover, the Badr Brigade was also a longtime enemy to the cult-like Iranian Mujahedin e-Khalq guerrillas stationed in Iraq—and the Mujahedin had fed (false but headline-grabbing) stories to both Tatchell and Ireland in the past.

But Sistani was also the one Shi’ite cleric whom the United States saw as potentially a force for “stability.” True or not, narratives that blamed him for the killings were unlikely to get much traction with a Western media that still took the coalition military forces as their main sources for Iraq events. Stories of “gay murders” stayed confined to the ghettos of the gay press.

ACT TWO: In early 2009, killings of LGBT people accelerated massively. What had once looked unsystematic became an organized campaign. When I went to Iraq, it was obvious that the forces of popular Shi’ite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr bore the main responsibility. Sadr City, the great Baghdad slum dominated by Moqtada’s movement, was the fulcrum of the violence; preachers there openly incited murder, and survivors blamed his Mahdi Army (Jaish al-Mahdi) for most of the carnage. Al-Sadr’s militia had gone underground at the beginning of the US-led counterinsurgency “surge” in 2007, and Moqtada fled to Iran. The killings seemed to be a bid to reassert his relevance and moral indispensability. One “executioner” claimed he was tackling “a serious illness in the community that has been spreading rapidly among the youth after it was brought in from the outside by American soldiers. These are not the habits of Iraq or our community and we must eliminate them.”

[Moqtada al-Sadr.]

Moqtada was also the right criminal at the right time for an American audience. The United States saw him as a prime enemy, driving Shi’ite resistance to the occupation. Blaming him was not just accurate but easy. His sinister dominance made sure the killing campaign got ample press in the United States and the United Kingdom.

What helped stop the murders, by contrast, was the growing indignation of ordinary Iraqis. One Baghdad journalist wrote in Sawt al-Iraq that

In addition to death threats against any man who grows his hair a couple of centimeters longer than the Sadri standards that are measured exactly and applied harshly, there are threats against those wearing athletic shorts or tight pants…The slogan is to kill and kill, then kill again for the most trivial and simplest things.

ACT THREE: The “emo” killings in 2012 also swirled around Shi’ite-dominated eastern Baghdad, and the Mahdi Army was widely held responsible, along with a breakaway Shi’ite militia, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq (League of the Righteous). However, Moqtada al-Sadr distanced himself from the campaign, saying emos should be dealt with only “in accordance with the law.” But this time, the Ministry of Interior, which had called for “eliminating” emos, was also involved up to the hilt.

[Flag of Iraq’s Ministry of Interior.]

And this culpability was inconvenient for the United States and its allies. Moqtada had now graduated to a force for “stability.” Meanwhile, the Interior Ministry’s repression held the country together. Demonizing the guilty was politically difficult from the American vantage. Dozens or hundreds died in Baghdad in a few weeks—a toll comparable to the hundreds probably killed in 2012. But the murders never drew the same international outrage, not just because emos were a vaguer target, but because the killers were not our enemies.

I do not mean US or UK forces deliberately manipulated coverage of the targeted killings. (They manipulated other stories; they did not have time for this one.) But Western reporters relied on coalition “experts” to analyze the jumbled politics of Iraq, acquiring their prejudices with their statistics. And even the gay press instinctively trusted that our side, however grave an error the invasion was, still had a righteousness that rubbed off on its allies. Politics shaped the coverage, and some of the accusations.

We perceive the perpetrators, like the victims, largely in relation to ourselves. When our enemies murdered gays, it was clear-cut evil. When our friends stood accused, the case was merely confused. It is a discourse about us; its ability to affect Iraq is therefore limited.

[Cover of the Arabic version of Human Rights Watch’s 2009 report on Iraq.]

Here is one instance. IGLHRC and MADRE, the international women’s rights group, released two briefing papers on violence against LGBT Iraqis in November 2014. They were solid work, based on a small but significant number of harrowing stories. What was striking is that both appeared only in English, with no Arabic version or even summary. Thus, while the reports included recommendations to the Iraqi authorities ranging from the feasible (“Amend the shelter law to allow NGOs to legally run private shelters for displaced persons”) to the fantastic (“Hold militias accountable”), those had absolutely no chance of affecting Iraq’s government, press, or public. (By contrast, Human Rights Watch’s 2009 report on death squads was released in Arabic, and headlined in Iraqi media.) The only audience the reports aimed at was an English-speaking one. And now, of course, the United States and United Kingdom no longer govern Iraq. Since the reports were meant for Americans but there was little for Americans to do, the advocacy seemed to acquire a slightly surreal quality. For example, the organizations told their followers (“Take action!”) to call on LGBT members of the US Congress to “stand with LGBT Iraqis.” This was less strategy than metaphor: it provided a way of making Americans feel they were having impact when they were having none. I do not wish to slight the groups’ excellent research, but the missed opportunity was painful.

It is pointless to imagine changing what Da’ish does. But there is a real opening to use Iraqis’ revulsion against its brutal murders—as well as violence targeting gender and sexuality elsewhere in the country—to affect public opinion and even a few policies in the rest of Iraq. As it was, from an Iraqi perspective, the reports were the former occupiers talking to themselves.

Da’ish, of course, has now seized a place in the West’s imagination as the ultimate enemy, the perfect storm. All evils meet there. (The Daily Mail warns that ISIS terrorists will “turn themselves into Ebola suicide ‘bombs.`”) Most of the earlier (probably more widespread) violence targeting sexuality in Iraq could be traced to Shi’ite militias or the US-supported state, but that is forgotten. The Sunni soldiers of Da’ish define homophobia. What Da’ish does is indefensible. Except when somebody else does it.

How Different Is Da’ish?

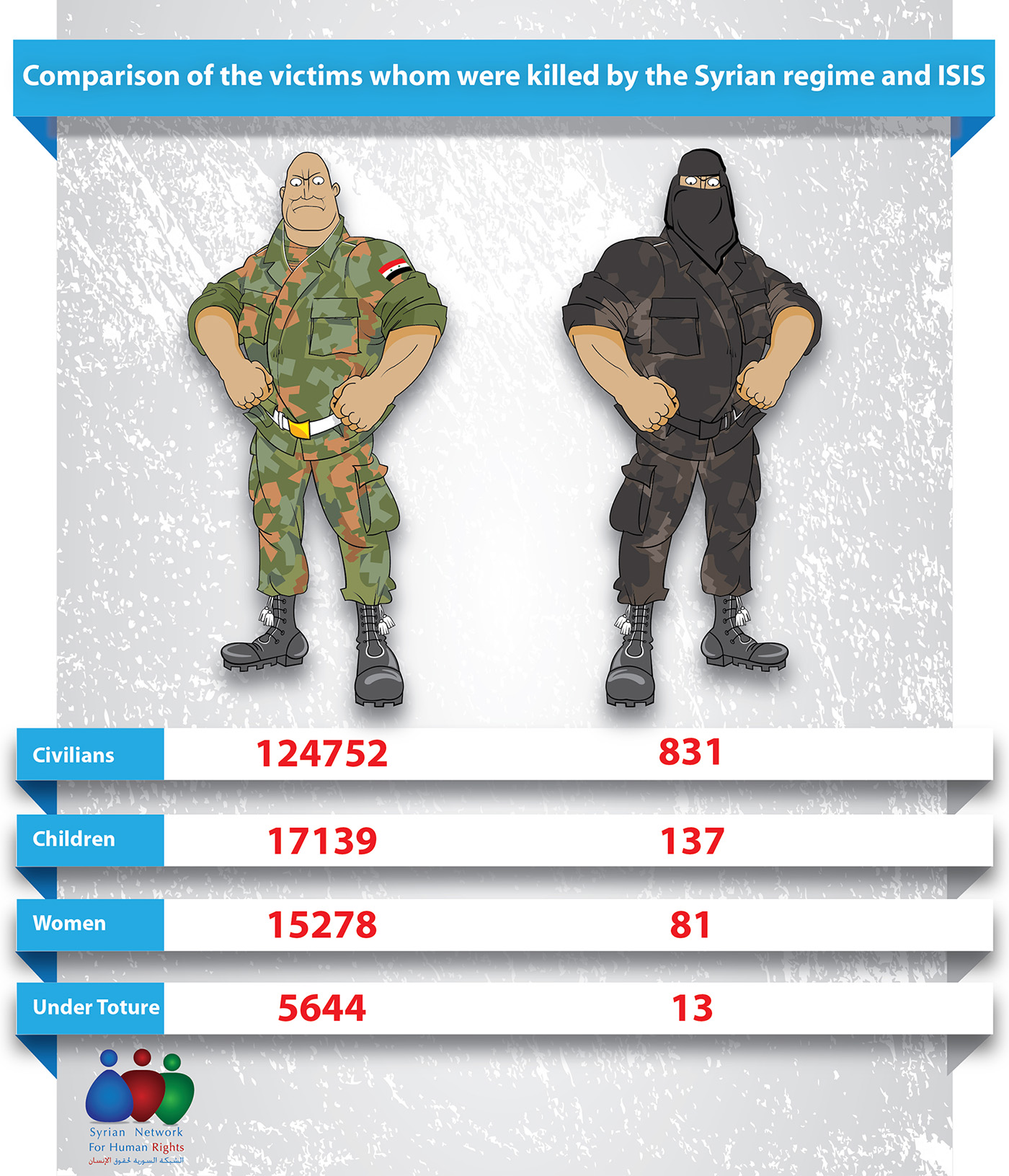

This little graphic from the opposition Syrian Network for Human Rights probably undercounts Da’ish’s murder toll, but its point is valid.

It charts the deep anger Syrian revolutionaries feel: How did a few viral photos of Islamist killings overwhelm the vaster, but mostly invisible, atrocities of a secular government the United States has learned to live with? Then there is that other Islamic state: the one due south.

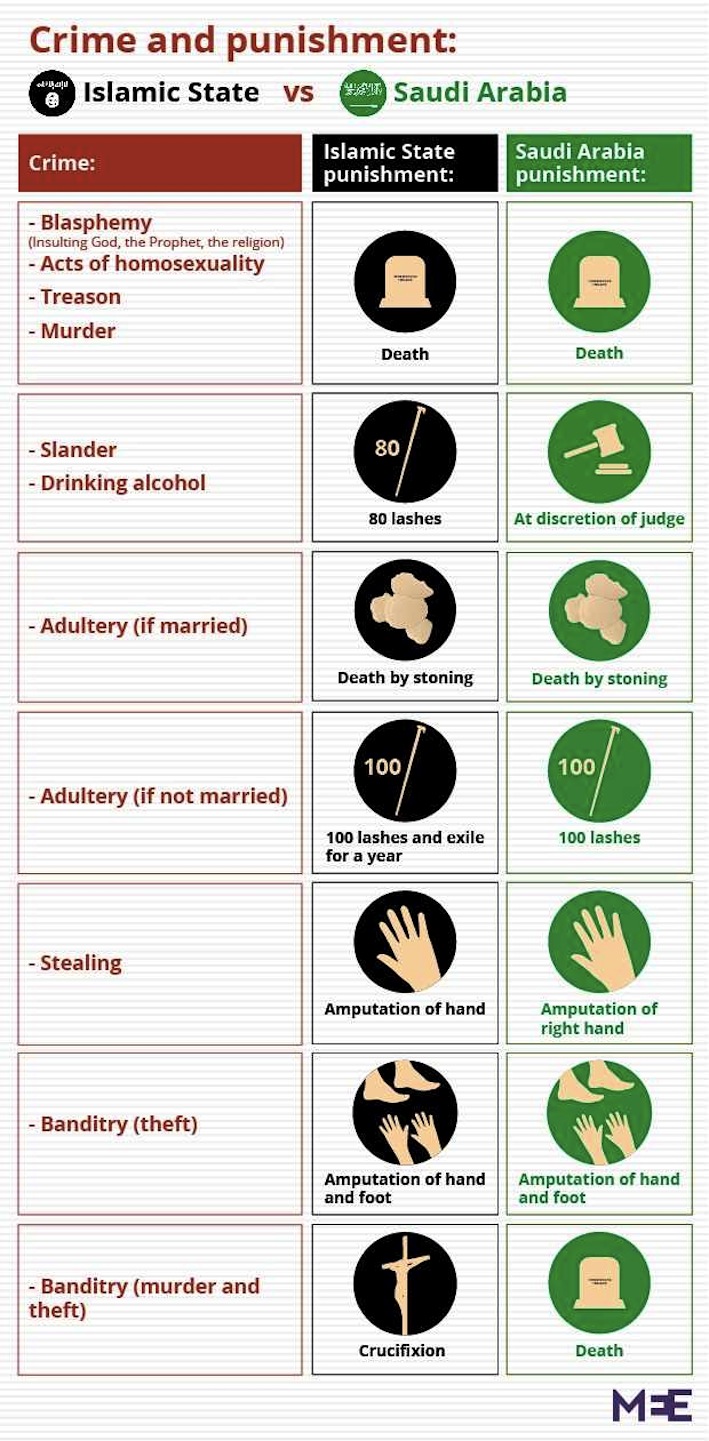

Middle East Eye published this graphic comparing Saudi Arabia and Da’ish after the latter released its own code of “Islamic punishments” last December. So how exactly is Saudi Arabia better or different, except that we call it a nation and not a terrorist organization? (A language, they say, is a dialect with an army. What is a state but a militia with oil reserves?)

In mid-January, we learned the UK Ministry of Justice set up a commercial arm with the Orwellian name of Just Solutions International, and is selling its expertise to Saudi prisons. Will David Cameron offer the shari’a courts of Da’ish a helping hand? A week later, we learned the US Department of Defense has launched “a research and essay competition” in honor of the late King Abdullah—“a fitting tribute to the life and leadership of the Saudi Arabian monarch,” to his “character and courage.” Will Obama also offer prizes for the best ISIS propaganda? Of course, Abdullah was a liberal and a progressive, the paid pundits say. Granted, he may have been the best of his venal, bloodstained clan, but that is like picking the most intellectual of the Kardashians. But give Da’ish a few years to sell oil to ExxonMobil. Then they will be “reformers.”

The real distinction between the two Islamic states’ degrees of violence is not severity but publicity. Da’ish, says Middle East Eye, “actively sought exposure for their brutal punishments, [while] Saudi Arabia has worked to keep evidence of their actions within the conservative kingdom.”

Why is Da’ish so proud of its sadistic excesses? Why does it broadcast them? Because they mean success. Here, again, the history of Iraq both before and after the US invasion is a shaping fact. For at least thirty-five years, violence, unrestrained violence, has been the mark of power. Power—under Saddam, under the occupation, and under the sects and militias that fought to seize his mantle—meant inflicting violence without shame, fear, or limit. (In a different way this was also true of Assad’s placid Syria, where despite the surface calm the dictator could kill twenty thousand Islamists with complete impunity.) When Da’ish posts its snuff films on YouTube and its death porn on Twitter, they are saying: We have the power at last, we can do this without restraint, and we will have more power and kill more.

[Photo of a mass killing of Shi’a captives after the fall of Mosul, posted on ISIS Twitter accounts, June 2014.]

Da’ish’s flaunted success also declares the failure of two projects that dominated the Middle East for decades. It proclaims the bankruptcy of the dictators’ project of state secularism. Regimes like Assad’s or Saddam’s repressed popular politics and popular religion with all the violence at their command in order to sustain a military elite’s privileges. And it puts paid to the US project of state-imposed capitalism. Neoliberal immiseration of the masses, the kind Mubarak planned for Egypt or the coalition imported to Iraq, could only be enforced by governments armed with maximum ruthlessness. Da’ish inherits their means while defying their ends. It bends their violence to its own agenda. The repressed have returned, with a vengeance.

The Egyptian leftist friend I mentioned at the outset comes from a working-class family that supported the Muslim Brotherhood. Some of them stood at Rabaa during the protests after Morsi’s overthrow; some could have been killed. Now, he says, he is frightened by how many of his relatives say Da’ish is the solution. They are not running off to join ISIS’s fighters (though the Da’ish franchise is increasingly an attractive banner for the insurgency in Sinai). But they no longer believe in a democratic outcome. They no longer grasp how a group like the Brotherhood could survive, let alone succeed, through the normal means of politics. Sisi is trying to follow in Assad’s and Mubarak’s footsteps, with a program whose legitimacy is the weaponry it can command. They see Da’ish as the only alternative. The known world is disappearing. There is emptiness underfoot. Violence is the future.

[A US Marine pushes corpses of Iraqi fighters, Fallujah, 12 November 2004. Photo by Anja Niedringhaus, AP]

[This article originally appeared on A Paper Bird: Sex, Rights and the World.]