While the eyes of the world focused on the intermittent occupations of Cairo’s Tahrir Square, in the four years since the Egyptian uprising of 2011, a different kind of social action has persisted at the city’s periphery. On 13 August 2010 and in February 2011, during the eighteen days leading to Hosni Mubarak’s fall, a group of 231 resettled slum dweller families from the impoverished Duweiqa district of Cairo abandoned their allocated twenty three square-meter homes to squat liveable ones in Haram City, a budget gated-community marketed by developers and development practitioners as a new best-practice “cooperative” public-private partnerships for low-income housing. Angered that publicly subsidized, but privately controlled, low-income housing was being sold to the middle classes, they joined families from all over central Cairo to claim several hundred flats, bringing water, electricity technicians, and microbus stands to coordinate transport to the city center. The Egyptian Army promptly intervened, and most squatters were evicted. The original Duweiqa 231 families, however, have managed to fight off all authorities and remain in Haram City to this day, bringing an economy and urban condition unprecedented for gated spaces in Egypt.

.jpg)

A purchased home in Haram City (Photo: Nicholas Simcik Arese).

Public-Private Partnership as Promise

A cornerstone project of Hosni Mubarak’s National Housing Initiative, Haram City was one scheme of the supposed million homes to be constructed between 2005 and 2010 to address Egypt’s much-discussed “housing crisis.” Completed in 2007, Haram City is majority owned and operated by Orascom Housing Communities, belonging to Samih Sawiris, one of three brothers in Egypt’s richest family.[1] On the premise of building a “fully integrated sustainable low income community,” Orascom purchased 4.8 Million square-meters of land in the desert behind the pyramids of Giza at a heavily subsidized rate of about 10EGP ($1.31) per square meter.[2] A minority share of Orascom Housing Communities is owned by US-based Equity International, an investment vehicle for Chicago billionaire and property magnate Sam Zell. Formerly the largest private real estate owner in the US, it is one of the companies most closely linked to the predatory mortgages of the US housing bubble. Since selling the majority of US real-estate holdings in 2007, six months before the crash, Zell promptly shifted focus to housing in emerging markets. Promoted by the UNDP Growing Inclusive Markets initiative as a best-practice public-private partnership and by the World Bank as part of its new low-income mortgage drive, Haram City copies are in discussion with the governments of Morocco, Romania, Turkey, Pakistan, Algeria, Ethiopia, Yemen, and Ukraine under the UN rubric of the human right to adequate housing.[3] In reality, with houses priced between 140,000 and 200,000 EGP ($18,360--$26,220), the scheme is entirely out of reach for Egypt’s lower two/three income quintiles, with a customer base that can be more accurately described as an aspirational middle class searching for a budget “compound” lifestyle, the Egyptian term for gated-community.

Occupied homes (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

From Tragedy to “Unsafe Areas”

Duweiqa is popularly understood by Cairenes as a quintessential case of slum crisis, a globally mediatized and circulated depiction of urban plight produced by the Egyptian government, Amnesty International, and various urban development organizations for the consumption of electorates and donors to advance both a range of anti-poverty agendas and grand urban revitalization schemes.[4] In 2007, Duweiqa suffered a catastrophic rockslide that killed more than 119 people and displaced several thousands. To this day, images of the crumbling site are on the front pages and front lines of designating entire swaths of central Cairo as “Unsafe Areas” requiring eviction to the city periphery.[5] The Duweiqa rockslide occurred just a few months before Haram City’s construction. Publicity and outrage around the incident, coinciding with the electoral populism of Mubarak’s Million Home initiative, compelled now-indicted housing minister Ahmed Al-Maghrebi to convince Orascom to take some families on board. This circumstantial compromise resulted in resettling families of an average size between five and ten people in twenty-three square-meter flats. Two years later, during Mubarak’s overthrow, Duweiqa residents who the governorate had deemed “undeserving” for resettlement either led or entered and defended against the squatter invasion, depending on who you ask.[6] In the process the original resettled group joined in to replace twenty-three square-meter homes for sixty-three square-meter ones, which they still squat together with relatives from the group of invaders who managed to evade getting cleared. Currently, Haram City contains about 30,000 inhabitants, approximately six thousand of which are a combination of resettled slum-dweller—the result of subsequent evictions from the Manshiet Nasr area in response to the Duweiqa rockslide—or resettled-turned-squatter and just squatter, as well as a few hundred Syrian refugees. The effort to stretch the definition of “low-income” by Zell and Sawiris to basically account for a market more accurately described as “budget gated lifestyle,” while benefiting from World Bank boosterism, has been turned inside-out.

A self-run youth club and home of “Haram City F.C.” in the resettled and occupied quarter (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

A garden is transformed into a gym in the occupied quarter (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

.jpg)

Members of the squatter community celebrating "youm al tangeed" (day of upholstery), where family of the prospective

bride publically display furniture offered to the new couple (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

Elaborate refurbishment of a purchased home (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

A Slum in the Gated-Community

As homes are taken and secured, squatters regularly question who the real thief is in this situation. Indeed, between the cronyism that led to many of the land allocations under Mubarak, and duplicitous promotion of an affordable cooperative as pretext for state subsidies, relative scales of theft and their comparative moral legitimacy must be publically confronted by any of the compound’s residents and management. Central to interaction across the class divide is the question: what and who is truly illegal urbanism here?

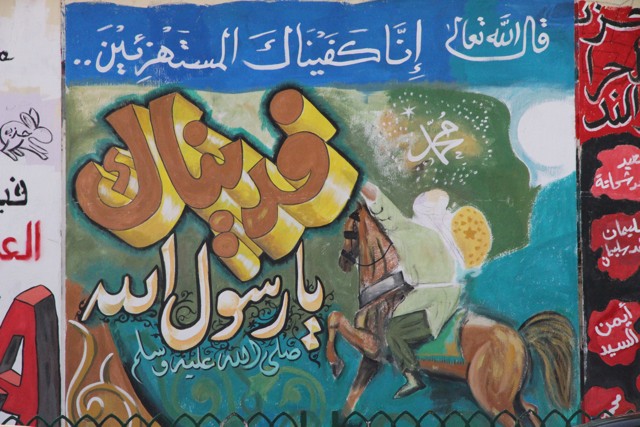

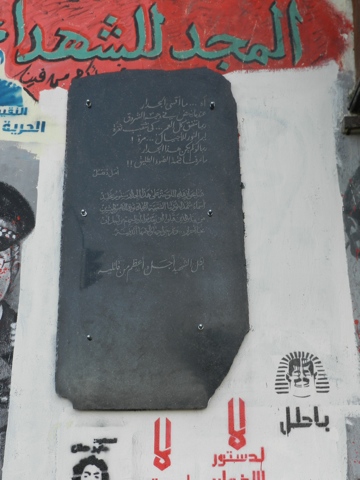

It is a viscerally acknowledged irony by the squatters themselves that the 10-15 EGP a day used to take three microbuses each way to work or school amounts to the same total as their pre-rock slide rent (200-300 EGP), minus three hours of good working time. Some have managed to find work gardening for wealthier residents, or constructing ornate walls for their overtly private domains. A few have found positions as security guards. Inevitably, though, an entire economy—and thus urban form—has begun to flourish within the occupied quarter. Houses are dismantled and reassembled, walls are knocked down between flats, picket fence front lawns are walled in and replaced with commercial spaces selling bread or clothing or a small gym, teetering pigeon coops jut from many roofs, goats and cows roam in certain lawns that operate as butchers with the freshest meat for miles, utilities infrastructure is hijacked and rewired, and a proper popular market of tin and repurposed timber has been constructed in what was planned to be a park. Across town, this area has acquired the name “Little Duweiqa,” as if a kind of ethnic enclave. Crossing the road between A1/A2 districts to B2 that delineates “Little Duweiqa” from the rest reveals the true formal difference as one walks by identical houses but in their original form, with neat ornate lawn walls and elaborate landscaping. The livelihood imperative for Little Duweiqa to shift, intertwine, and expand as it attempts to invent an economy for itself has been labeled by many home-owners as the “slumification” (ba’a ‘ashwaa’ee) of the gated community. The Haram City Activists Association, a group of home-owners that meets bi-monthly to discuss the matter, runs several Facebook groups deriding and lamenting the gaze of “Egyptian crowds” (al zahma masreea) outside of the law as the very raison d’être behind fleeing to the desert.

A self-built mobile-phone shop in the occupied quarter (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

"Souq Duweiqa," a fully functional market constructed by squatters (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

An occupied home for sale (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

Why Haram City Matters

Amidst a tabula rasa project, residents are forced to reconcile their expectations and perceptions of the new Egyptian city with daily confrontation. Many of the expected ownership patterns of Cairene life are deeply altered, with homeowners only controlling long-term usufruct rights (including severe regulations on any construction/modification) and squatters seizing pre-built homes. With only ten percent of real property registered in 2006, low expectations over the protection of home ownership might be assumed. Yet, contrary to the overwhelmingly dominant form of informal construction and land occupation, or wad’ al yad (literally ‘put a hand on’), the Haram City occupation is not an illegal subdivision, nor is it a construction without permit or a violation of land use ordinances; it does not violate the Urban Planning Land Act (Law No. 3 of 1982), the Building Code (Law No. 106 of 1976), the Status Law (Military Decree No. 7 of 1996) regarding subdivision and construction, or Law No. 53 of 1966 and Military Order No. 1 of 1996 regarding land use regulation like ninety per cent of new constructions in Cairo. The invasion and occupation of pre-existing vacant homes is extremely rare and unprecedented in the context of a fully private enclave.

To this day, all charges brought upon the squatters have been presented as “breaking and entering,” the destruction of private property (furniture and doors), and vague accusations of “criminal activity” beyond the space of the house, never mentioning illegal construction or occupation of lands. As property scholar Carol Rose notes “visibility runs through property law as perhaps no other legal area,” and in this sense the squatted homes may not be welcome but are perceptually not irregular.[7] Indeed, in walling in the gardens of their squatted homes, the Duweiqa community rigorously respects Orascom’s regulations on wall heights (seventy five centimeters of cement or brick from the ground, with anything above in light metal or plants), in stark contrast to many titled home-owners by purchase, who often have walls well over two meters. Struggles over the rights (and rights for whom) that will define ownership are immediately consequential and publicly disputed.

Two purchased homes refurbished and joined into one property (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

A resettled resident transforms his front lawn into a couch shop (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

Even if out of reach to Egypt’s bottom three income quintiles, Haram City is the first major suburban gated residence affordable to the aspirational middle class – what many of the compound’s youth in-turn label as exemplary of the Hizb al Kanaba (literally “the Couch Party) for their explicit political ambivalence prioritizing stability. For the first time, one can compare the expectations, disappointments, and narratives of Egypt’s new middle class finally able to move to the suburb with its everyday lived reality. On the other hand, the Duweiqa squatters may represent a proto-movement, largely disconnected from contemporaneous revolutionary activity in the country. Understanding how the poor identify or reject social-justice struggles, even as they carry them out through practices more generally dismissed as “informal,” is central to understanding the extent of inclusivity and pluralism of dominant activism.

In a more global sense, Haram City is one of the flagship projects for new UNDP/World Bank drives to securitize lower-middle income potential homeowners in the Global South through subsidized mortgages. Most major real-estate conventions now devote entire sections to the vast uncharted opportunity for public-private partnership housing across the South, and numerous US property speculators closely linked to the housing bubble have shifted towards this opportunity in light of their own struggling markets. The rise of cheap housing loans in the Global South is unprecedented and, as testing-ground for numerous plans globally, “affordability” in Haram City interacts with social vectors—such as the relationship between housing, masculinity, and marriage—in understudied, but prescient, ways.

Children from the squatter community sell children’s goods to residents of purchased homes (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

.jpg)

Squatters watch the news at a cafe in “Souq Duwieqa” (Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese).

Conclusion

As activists lament that the social justice aims of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution feel increasingly like an illusion, research is necessary on the documentation of ongoing social-justice struggles in Cairo, though they may not be framed as revolutionary by the participants themselves. Despite a strong clamp-down on improvised livelihoods in Egypt, “quiet encroachments” on the material and legal status-quo have taken new forms, in some cases out-in-the-open.[8] Haram City and the Duweiqa squatters within present a peculiar case study. Here one finds the greatest binary tropes of urbanism in the South—the slum and the gated-community, the formal and the informal, protest and “quiet encroachment,” the precarious urban core and elite periphery, completely intertwined. As such, Haram City has become a locus for broad public dialogue on how the urban poor in Cairo think about rights, ownership, and protest in the city.

A similar version of this article was originally posted on Cairobserver

---------------------------------------

Notes

[1] For a depiction of Haram City as it is explicitly marketed to soon-to-be-married youth, see one of the first advertisements for the compound “Your dreams before you.”

[2] Shawkat, Y. (2014). Mubarak’s Promise. Social justice and the National Housing Programme: affordable homes or political gain? Égypte/Monde Arabe, 3(11).

[3] For the range of expansion plans in discussion see: Orascom Housing Communities. (2007). Annual Business Plan (pp. 1–26). and UN-HABITAT. (2014). The State of African Cities 2014: Re-imagining sustainable urban transitions (p. 273).

[4] Amnesty International. (2011). “We are not Dirt”: Forced Evictions in Egypt’s Informal Settlements (p. 113). London.

GTZ. (2009). Cairo’s Informal Areas: Between Urban Challenges and Hidden Potentials (p. 224).

[5] see: General Organization for Physical Planning, Ministry of Housing, & UN-HABITAT. (2010). Cairo 2050: Greater Cairo Region Urban Development Strategy Cairo. (p. 188).

[6] Given ongoing legal proceedings against the squatters, the specific order of invasion and role played by the Duweiqa squatters remains highly contentious and disputed. In interviews, Haram City management contend that squatters invaded and encouraged others to do so. The Duweiqa community, on the other hand, distinguishes their invasion as legitimate given their history of resettlement and therefore the self-evident imperative to protect against other invaders to reinforce their claims.

[7] Rose, C. M. (1994). Property & Persuasion: Essays on the History, Theory, and Rhetoric of Ownership. Westview Press. (pp. 267, 269).

[8] Bayat, A. (2000). From `Dangerous Classes’ to `Quiet Rebels`: Politics of the Urban Subaltern in the Global South. International Sociology, 15(3), 533 –557.

![[Empty homes in Haram City. Photo Nicholas Simcik Arese]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/Figure1_duweiqa.jpg)