Zeinab Abul-Magd, “Bringing The Economy Back in!”

Issandr Al-Amrani, “An Optimistic Rejoinder to Jason Brownlee”

Nathan J. Brown, “Don’t Worry, Be Happy”

Daniel Brumberg, “A Revolution or a SCAF-Managed Transition?”

Mohamed El-Menshawy, “SCAF Cannot Defeat the Square”

Samer Shehata, “Citizens and State in Post-Mubarak Egypt”

Jason Brownlee, “A Final Response”

“Introduction,” by Hesham Sallam [open in separate window]

Almost six months have passed since former Vice President Omar Suleiman appeared on television to announce to the world that 30 years of Hosni Mubarak’s rule have ended. As monumental and decisive as Mubarak’s defeat was, it remains unclear (or perhaps unsettled) who exactly emerged victorious in this battle: The millions who rallied in public squares in Cairo and beyond demanding the downfall of a regime that failed its people on multiple counts, or the range of political, bureaucratic, and socioeconomic forces that saw in Mubarak’s ouster an opportunity to preserve (whether collectively or separately) the core foundations of the political order over which Mubarak presided and that has long protected and advanced their narrow interests?

Jason Brownlee’s recent piece in Jadaliyya “Egypt`s Incomplete Revolution: The Challenge of Post-Mubarak Authoritarianism” cuts through the heart of this question by highlighting just how contested and difficult the battle against Egyptian authoritarianism has become ironically at a time when every political actor in the country—including its de facto military rulers—claims to speak on behalf of the revolution and its democratic aspirations. Brownlee tells us that the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) is doing much more than just sponsoring a constitution writing process and election schedule that will reinforce the uneven political playing field that Egypt inherited from the Mubarak era—a point on which many observers of Egyptian politics (myself included) have focused. More importantly, he warns, the Council’s policy of keeping Mubarak’s core repressive apparatus—the ministry of interior and its affiliated security organizations—out of the reach of serious reform efforts, “ensures authoritarianism by default” and will likely limit the prospects for democratic change in post-Mubarak Egypt.

Taking Brownlee’s sobering analysis as a springboard for discussion, I invited a roundtable of distinguished group of scholars and researchers who follow Egyptian politics closely to provide their own assessment of where Egypt is heading at the moment. I asked participants whether they see evidence that Egyptian authoritarianism is in fact reconstituting itself with the aid of the SCAF. I also asked them to reflect on the factors and processes that will likely shape the quality of accountability, transparency, participation, representation, and inclusiveness of post-2011 Egyptian politics.

Two broad points emerging from this roundtable are worth emphasizing.

First, while all respondents agree that SCAF’s actions have been anything but supportive of democratic change in Egypt, some do not share Brownlee’s pessimism and believe that Egyptians still have a fair shot at achieving the democratic goals of their revolution.

Notwithstanding the seriousness of the challenges ahead, Nathan Brown sees a lot of promising changes in Egyptian politics, pointing to the vitality of political contention and participation, growing public demands for greater government accountability and transparency, as well as the “mini-revolutions” that are happening in the media, universities and unions. As easy as it is to conclude that Egypt is doomed, Issandr Al-Amrani writes, it still remains that battle for the country’s future is unresolved and that the opportunity for achieving transformative change has never been better in the last half century. Echoing this same point, Mohamed El-Menshawy adds that even though military leaders have a strong interest in limiting the scope of reform, it is hard to imagine them succeeding in the face of powerful protests and wide public scrutiny campaigns. Irrespective of their anti-democratic inclinations, he concludes, SCAF’s options may be too limited to succeed in containing popular demands for democracy.

Second, analyses seems to converge on the conclusion that the long-term battle for democracy in Egypt is unlikely to hinge entirely on elections, but will probably center on unaccountable sectors of political power inside the Egyptian state, most notably: the Ministry of Interior and its affiliates, military institutions, and bodies and agencies responsible for setting economic public policies and priorities. The battle to make these critical sectors more transparent, accountable and responsive to public demands could very well shape the major features of the post-Mubarak regime in Egypt. Concurring with Brownlee about the pressing need for overhauling the existing security apparatus, Samer Shehata offers a nuanced explanation of what needs to be done to turn the Ministry of Interior from an instrument of repression and control to a force for protecting and upholding the rule of law. Achieving these goals will not be easy and will require a great deal of political commitment, resources and time, as Daniel Brumberg reminds us. He indicates that previous experiences of security sector reform in transitional countries demonstrate the difficulty of completing such reforms during the early stages of a transition such as the one Egypt is currently facing. Brumberg also highlights the tough tradeoffs involved in trying to reestablish security and law-and-order in the short-run while simultaneously advancing efforts to purge and reform the security apparatus. The challenges do not stop at the security sector or even the military institutions that are currently controlling it. Zeinab Abul-Magd’s contribution stresses that the economy and economic policy making remain largely untouched by this revolution, despite the enormity of the socioeconomic disparities that made many Egyptians rally in demand for Mubarak’s downfall. She suggests that unless economic policymaking becomes more participatory and responsive to the demands of the revolution, specifically aspirations for greater distributive justice, efforts to reform electoral and security institutions will fail to bring about the change that Egyptians want and the new political order will be devoid of popular support and legitimacy.

In sum, it seems that the challenges ahead for Egyptian advocates of transformative change will remain formidable and strenuous—at least until the overwhelming power of the Square, yet again, proves us wrong.

Below is the text of roundtable’s contributions organized alphabetically by authors’ last name, followed by a brief response by Brownlee.

Zeinab Abul-Magd, “Bringing The Economy Back in!”

Issandr Al-Amrani, “An Optimistic Rejoinder to Jason Brownlee”

Nathan J. Brown, “Don’t Worry, Be Happy”

Daniel Brumberg, “A Revolution or a SCAF-Managed Transition?”

Mohamed El-Menshawy, “SCAF Cannot Defeat the Square”

Samer Shehata, “Citizens and State in Post-Mubarak Egypt”

Jason Brownlee, “A Final Response”

“Bringing The Economy Back in!” by Zeinab Abul-Magd [open in separate window]

I agree with Jason Brownlee that Egypt does have an “incomplete revolution” and is experiencing an era of “post-Mubarak authoritarianism.” I also support his argument that SCAF’s undeclared policy of maintaining the old security apparatus while pursuing limited reforms, such as the unsatisfying cabinet reshuffle recently announced, is key to preserving the old authoritarian structure in the country. I would argue, however, that while most activists and researchers are focusing their attention on the security apparatus, which was already weakened by the revolution, the economic factor, as a matter of fact, is more fundamental in preserving the old authoritarian order of things now under the military regime. Controversy about the Ministry of Interior seems to many like an elitist matter that close circles of activists and academicians only care about. Switching the attention of public and scholarly debates from security apparatus to socio-economic aspects of the current situation not only takes us back to the original reasons behind the revolution, but it also secures and guarantees the street’s support in getting it complete.

During the last twenty years, Mubarak’s authoritarianism thrived mainly due to its commitment to pursuing economic reform policies in accordance with “Washington Consensus.” In fact, one of the Ministry of Interior’s main tasks was to crush public resentment against market measures and their negative implications. For the last six months, SCAF ignored any demands to revaluate these policies, especially after U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s visit to Egypt last March. The IMF and World Bank’s blueprint of market reforms in Egypt, whose application was exacerbated by Gamal Mubarak’s “Policies Committee” of the ruling party and the businessmen-controlled government of the last seven years, helped generate massive corruption and tremendous social disparities. For example, corrupt-ridden privatization deals allowed a small number of pro-Mubarak Egyptian business tycoons and foreign investors to buy state enterprises at ridiculously cheap prices, and subsequently lay off hundreds of thousands of workers. In addition, liberalizing laws governing agricultural land rents and elimination of subsidies led to considerable impoverishment of Egyptian small peasants, migration from the countryside to the city, and growth of slums and urban poverty. It was the byproducts of U.S.-designed market reforms, which opened the door to crony capitalism and severe social injustice, that pushed millions of citizens to take to the street in January 25th revolution. The brutal security apparatus that attacked the protesters was not only protecting its own survival and interests but, more importantly, the interests of the small elite of business tycoons who benefited from the withdrawal of the state from the economy and controlled it through its clientlist relations with Mubarak’s family.

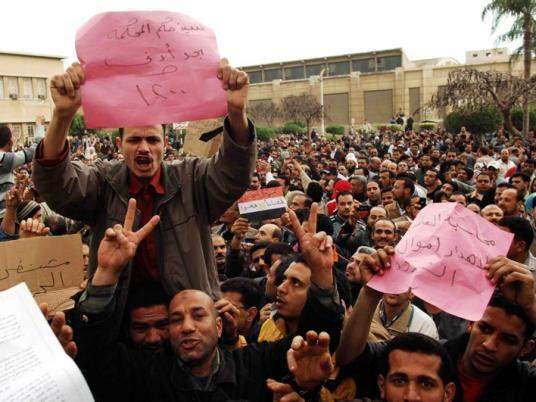

[Workers from Mahalla Textile Company on strike (February 2011). Image Source: Al-Masry Al-Youm]

U.S.-sponsored model of market economy, or the dogma of neoliberalism, was undoubtedly an integral part of creating and fostering Mubarak’s authoritarianism. Thus, reversing U.S./Gamal’s measures of market reform is the logical outcome of the revolution. But the SCAF seems to have other plans as it continues to uphold these measures and avoid addressing public controversy surrounding these policies. The security apparatus is only a protector of the existing economic order and the interests of its narrow circle of business elite that maintain it. Thus, I believe that public and scholarly efforts should be redirected to address the economic foundations and causes of Egypt’s authoritarianism.

Despite the lack of documentation about the military council’s members involvement with corrupt business tycoons, evidence is gathering here and there as I tour Upper Egyptian governorates about close ties between military institutions and private business community. I have encountered numerous stories in the southern governorates of Aswan, Luxor, Qena, and Sohaj about the close partnership between the military and infamous figures in the business elite. In his article, Jason Brownlee refereed to a New York Times piece about the great degree of military control over Egypt’s economy. The SCAF has not privatized the state assets it manages, but it rents them out or conducts business through them with Mubarak’s old corrupt tycoons. In this respect, preserving neoliberal policies is an important part of protecting SCAF’s privileges in the economy and keeping it beyond the reach of public accountability and transparency.

As for September’s parliamentary elections, I believe they would not lead to anything more than minimal changes to the current situation. I agree with Brownlee that such elections will bring about a parliamentary majority consisting of ex-NDP members and Muslim Brotherhood candidates. Neither of these groups has any interest in reversing U.S.-designed market reforms nor do they seriously care for social justice in their written platforms. They are both allies of the SCAF and are likely to continue to obscure economic debates in the legislature. Without giving new political parties, especially the ones with leftists agenda, enough time build their membership base and develop their platforms, the upcoming elections will only foster old authoritarianism and reproduce military despotism supported by religious rhetoric.

I am afraid that while Egyptian activists and international academics are focusing on criticizing the obvious or what seems to be an elitist issue that only a narrow circle of political campaigners care about, i.e. the security apparatus, they are ignoring the more important aspect of post-Mubarak’s authoritarianism. As long as the SCAF overlooks altering neoliberal policies in Egypt, old business tycoons and their allies will remain in power and win local and parliamentary elections, the military institution will continue to financially benefit from this business elite’s corruption, and the ancien régime will prevail. If we redirect our attention to the socio-economic conditions and the issues that affect the daily life of Egyptians in Cairo and in the southern and northern governorates, only then we can secure the full support of the street to get this revolution complete.

“An Optimistic Rejoinder to Jason Brownlee,” by Issandr Al-Amrani [open in separate window]

It is hard to find fault in the narrative described by my friend Jason Brownlee’s article on “Egypt`s Incomplete Revolution.” He is correct to point out that no real reform of the security services is yet underway. He is right in thinking that the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), headed by Hosni Mubarak`s jaundiced defense minister of some 20 years, Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, is not a force for democracy. Few in Egypt, notably among the protest movement that sparked off last January’s uprising, are happy about the transition phase so far — as the presence of thousands of them on several cities’ main squares indicates. Even if, as Brownlee notes, the civilian security services under the aegis of the Ministry of Interior have been winded by their defeat on 28 January, they are now recovering and their military counterparts appear to have been schooled in the same brutal methods.

I would add to this that the class dynamics that sustained the Mubarak regime, pitting a small (if somewhat growing) globalized elite against a permanent underclass associated (in the former’s imagination) with danger and chaos, have not fundamentally changed; that the most important of the state-controlled media, the television channels that seek to influence the worldview of millions of Egyptians, are still outrageous propaganda outlets; that much of Egypt’ss political class is either woefully unprepared or so steeped in the bad old habits of Mubarakism that it eagerly awaits a signal for co-option; that foreign powers (Arab and Western) are busy plotting the return of a predictable rather than democratic and thus, at least initially, uncertain government in Cairo; and that 60 years of authoritarian mismanagement have placed the entire country in such a perilous socio-economic situation that one can’t hold a grudge against the many ordinary citizens for whom stability and order might be a higher priority than democracy. Need I mention that the economy is not doing too well either?

[Tahrir Square demonstrations. Image from unknown archive]

I am not an academic, and cannot refer to the body of literature that might accurately describe the present Egyptian predicament. I would merely note that, in many respects, it is easy to conclude that Egypt is screwed.

Yet, Brownlee — like many who wrote of the persistence of neo-authoritarianism in the Arab world — is too pessimistic. His understanding of what might be a desirable outcome is also too limited. For instance, in pointing out that new political parties and the “revolutionary forces” of Tahrir might not perform well in upcoming elections, he minimizes the fact that democracies have little alternative to elections to decide their leadership. Like some liberal forces in Egyptian politics, he describes the result of an admittedly very flawed referendum last March as a defeat for democracy. Let us remember that the main force for a “yes” vote in the referendum was an eagerness for a rapid transition and a return to civilian rule. Simply because we do not like the Islamist current, which backed this choice, does not mean it was the less democratic one. Indeed, it might do us well to remember that many self-described liberals were for years eager to look the other way when the Mubarak regime tortured and arrested Islamists, socialists and other “radicals”.

This, one must stress, is not true of the revolutionary movement, which became possible partly because of a historic reconciliation between new generations of leftists, liberal and Islamist activists. Yet, revolutionaries are not bound to become the new rulers, and this is not a particularly bad thing. The Muslim Brothers will do well in the upcoming elections, as will Salafists. Some former members of the National Democratic Party will undoubtedly be elected again, particularly in rural areas. But the truth is it is hard to say what Egypt’s new political landscape will be next year — indeed the elections will be crucial in providing some clarity on this. The key thing is not that they should be free of fraud — like elections in India and many developing world democracies (democracies function fundamentally differently in countries with mass poverty), there will be vote-buying and violence. What is important is that the state refrains from participating in the fraud.

It is too early to see any broad trends emerging in Egypt that would indicate either successful democratic transition or the triumphant return of authoritarianism. As I write these lines, protestors have reoccupied Tahrir Square for the sixth day, the minister of interior has just fired 600 police generals, the SCAF just grudgingly accepted to draft guidelines for the upcoming constitution and the selection of the constituent assembly. Protestors continue to demand an end to military tribunals and the criminalization of strikes. It is true that the Emergency Law has not been revoked (although when, in the last 30 years, has the situation so much resembled an emergency?) but the SCAF has committed to do so by September. There is one crucial thing to remember: the moral authority of the regime evaporated some time ago, long before January 25. There is no sign that Egypt’s interim rulers have regained any of this legitimacy; indeed they seem to be barely hanging on. They may be defining the boundaries of the transition but not its momentum.

Egyptians expect to have to fight for every democratic advance they’ll achieve, and are increasingly clear-eyed about the challenges they face and the resistance they’ll encounter from the military and state administration. But never for the last half-century have they had a better opportunity to make change happen. There is a growing, broad consensus across the political spectrum on the need for democracy, respect for human rights, and better governance and accountability. (Let us remember that not so long ago, many Islamists, Arab nationalists, and even some leftists were skeptical about parliamentary democracy — only few are today.) There are new reasons every day to believe that this change can come over the next decade, however painfully. Let us not prejudge the outcome: we are still in a time of infinite possibilities.

“Don’t Worry, Be Happy,” by Nathan J. Brown [open in separate window]

Jason Brownlee is right. Egypt is still led by a military leadership that has few democratic credentials; the transition process was badly designed from the beginning and continues to be confusing and uncertain; decision making in Egypt has become even more opaque; the thuggishness and unaccountability of large parts of the Egyptian state have gone unaddressed; and the opposition that pulled off a revolution is very much in disarray—and it remains in opposition.

Looking forward there are many causes for concern.

But looking backward, it is still remarkable what Egyptians have done. And perhaps it is because I am a bit historically minded that I am still optimistic. But it is not obscurantism alone that can encourage an observer. In fact, a Janus-faced look at Egypt today in light of the country’s past and future give real reason for hope.

For all the messiness of the current political situation, there are four developments that lead me to a guardedly more cheery attitude.

First, elections are coming. Yes, the electoral law is confusing and Egypt’s electoral machinery may not be well positioned to handle truly competitive voting. But very soon there will be new sources of authority in Egypt as well as voices that Egyptians have clearly authorized to speak on their behalf. Tens of thousands of people chanting demands in public squares throughout Egypt will be joined by millions voting—and those voters will be selecting among genuine choices. Some of the older political forces will manage the transition to more democratic elections, but none will remain unaffected by it.

Second, the language of political discussions in Egypt has become remarkably participatory, sophisticated, detailed, and focused on fundamental questions of governance. The demand for accountable government—and indeed, for mechanisms of both vertical accountability (in which political authorities are accountable to the people) and horizontal accountability (in which political authorities keep an eye on each other)—has grown strong indeed.

Third, power has been dispersed. No, there is little likelihood that the military will disappear as a political force, that formerly dominant elites will be totally displaced, and that figures who made their peace operating under the old regime will slink away in disgrace. But the domination of the country by an imperious presidency and its sycophantic and venal followers is gone and will be difficult to recreate.

Fourth, the mini-revolutions that accompanied the January 25 revolution-in the media, the universities, the unions, and in other institutions in Egyptian life-have not spent all their force.

["The Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions supports the demands of the people`s revolution and calls for a general strike of Egyptian workers," reads a banner in Tahrir Square. Image Source: Reuters]

What a longer-range perspective can help us realize is how different Egyptian politics is likely to be—and indeed how much has been achieved by revolutionaries who ensured that the phrase “Egyptian politics” is no longer an oxymoron. Increased participation and pluralism are already notable. Yes, greater social and political justice have not been achieved, but avenues are emerging where such concerns can be pursued.

Democracy is beautiful; democratic politics is often ugly. Some of the currently disturbing elements in Egyptian politics are sometimes a mark of how far Egyptians have come. That the military now strives to find some guarantees that it will be immune from civilian oversight; that some liberals and others abandon some democratic principles in the face of an Islamist challenge; that many Islamists use their expected popularity as a reason to abandon their attempts to reassure their opponents—none of these developments is pleasant. But every one is a vivid reminder of reborn political contention. And each is also a mark of a new political environment in which no single force or power can dominate and in which Egyptians of various political orientations will have to argue, compete, and cooperate with each other over the country’s political future.

“A Revolution or a SCAF-Managed Transition?” by Daniel Brumberg [open in separate window]

I could not agree more with Jason Brownlee’s thesis that Egypt’s military leaders are not “Self-abnegating stewards but shareholders in the authoritarian status quo.” But it is hardly surprising—and indeed quite predictable—that the overall strategy of generals is to shape a transition that maintains a good part of the old order. Such an effort is in keeping with the typical transition strategy of most military leaders faced with similar constraints, as the drawn out and often agonizing experiences of Brazil and Chile amply demonstrate. Indeed, take away the word Egypt and substitute Brazil, and you will find a strikingly similar story. After all, Egypt is not in the middle of a revolution—whatever the aspirations of those who helped to topple former President Hosni Mubarak. Instead, it is going through a managed transition the parameters of which are largely being determined by ancien régime forces. Given that the latter’s resources far outstrip those of the disorganized Tahrir democrats, and given the Muslim Brotherhood’s evident interest in “playing ball,” the diverse non-Islamist opposition groups must decide how to secure maximum leverage in a context that disfavors them.

On this score, Brownlee advocates shifting the focus from electoral engineering and constitution making to actions designed to “deconstructing the security state.” I partly concur with this prescription. Indeed, as I note in a recently published Atlantic piece, I think the campaign to re-sequence the transition—by securing a constitutional document before elections are convened—is a waste of valuable organizational energy. But the deconstruction of the security state is also a huge project that will take years to advance.

True enough, the original transition literature had little to say about this challenge, other than emphasizing the need for pact making—which of course implied making some kind of concessions to those forces that control or are linked to the security apparatus. But there is now an ample literature, which, if not quite “ambrosia to political scientists,” certainly is helpful. This literature includes a vast number of conceptual and empirical studies on “transitional justice,” as well as practical work on civilian reform of military institutions –some of which can be accessed (by the way) on the web page of the United States Institute of Peace. The latter’s field experience in both transitional justice issues and civilian reform of security/military institutions suggests a complex and prolonged sequence of initiatives, reforms and actions, few of which can be pulled off at the early stages of a transition.

[Egyptian police protest low wages in front of the Ministry of Interior, as army soldiers stand guard atop their armored vehicle in Cairo, Egypt (March, 2011). Image Source: AP]

In the case of Egypt, we are talking about a security apparatus that grew from some 120,000 in the early eighties to 1.2 million by 2010—a veritable monster that preyed on the population. When I was in Cairo recently and discussed the challenge of extinguishing this monster, most experts—including not a few democratic activists—argued that this endeavor would require massive institutional, human and economic resources. But there was considerable disagreement as to how to go about this, or what the proper and most propitious sequencing of this project was, particularly in the context of Egypt’s on-going, wider transition. After all, every strategy involves trade-offs. Continued mobilization in Tahrir comes at the expense of organizing parties and coalitions. (This point is particularly salient given the Muslim Brotherhood’s evident desire to avoid antagonizing the military, and even more so, its primary strategic goal, which is to achieve some measure of power by hook or by crook). The push for trials of former regime members could very well undercut the judiciary’s quest to establish its independence and integrity. And then there is the question of security itself, which must somehow be reestablished but without putting the same old apparatus in charge.

All this points to the following: first, the continued relevance of keeping the overall political transition on track and slowly, fitfully moving forward to reasonably fair elections, which for logistical purposes will not possibly be held according to the military’s overly rapid time table; second, the need to sustain the campaign for a democratic-pluralistic constitution, a project that can and indeed has already begun, but which—for better or perhaps worse—will only happen after elections.(Whether the SCAF’s decision to establish a committee to set out “core constitutional principles” before the election advances or retards this project is an open question). This sequencing may be far from optimal, as ‘Doctors of Transitology’ would argue. But the overall science of transitions—to the extent that it can be called a science—still have something to say, as does the ample post-transitions literature on hybrid regimes (that I have not discussed here but which is surely known to your readers) and the above-mentioned literature on transitional justice and civilian reform the military. All of this work must be mobilized and selectively used in a context, which is neither exceptional nor surprising.

“SCAF Cannot Defeat the Square,” by Mohamed El-Menshawy [open in separate window]

Brownlee’s assessment of SCAF’s role coincides with growing public skepticism of its leadership in Egypt, which has become more widespread and visible in the past weeks. For example, when I visited Cairo last April and participated in the “Friday of Cleansing,” many protesters told me they were frustrated with the SCAF’s failure to respond to the revolution’s demands, yet direct criticism of the Council remained very minimal. On July 8, or the “Friday of Determination”, I had completely different experience at Tahrir Square where I spent several hours talking to protesters and listening to speeches by various political figures. The SCAF was the main target of criticism by several groups and protesters openly called for the removal of Field Marshall Mohamed Hussein Tantawi. Many people accused SCAF of manipulating, if not fighting against, the popular revolution. One member of the Revolution Youth Coalition told me “SCAF still doesn’t get it. It’s a full revolution! We do not need partial solutions nor passing our demands to the next elected president and government. They should understand the uniqueness of this period of Egypt’s history and not try to run Egypt as ‘business as usual.’” Another activist remarked, “This was not a revolution only against Mubarak and his family. It was against the entire regime”.

This month witnessed two notable developments that cast further doubt on SCAF’s self-proclaimed democratic commitments. The first is the appointment of Osama Haikal as minister of information, which many consider a set back for freedom of the press in Egypt as it signals SCAF’s interest in keeping the Ministry (and its control over freedom of information) intact. The second is a front-page photo in newspapers showing Ahmed Shafiq, Mubarak’s last prime minister sitting along side Field Marshall Tantawi and SCAF’s Vice President General Sami Enan at the graduation ceremony of the Air Force Academy.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s decision to take part only in the July 8th protest and not to participate alongside other groups in the subsequent “sit-in” organized in Tahrir Square is very telling. While on the one hand, it demonstrates the Brotherhood’s muscle and capacity to rally supporters, it stands as yet another proof that the Brotherhood is the only group that the SCAF could rely on to balance against the demands of liberal and leftist political forces.

That being said, while SCAF would like to see the scope of this transition contained, the Council faces limited options and none of them is to reconstitute or reinvent Egypt’s authoritarian past. The persistence of widespread popular protests and demonstrations, coupled with unprecedented level of public scrutiny of government, makes this an impossible task. Egypt is witnessing for the fist time in its history a direct media scrutiny of its leaders. Head of SCAF Field Marshall Tantawi is often criticized by name in mainstream media outlets and public discussions. An authoritarian resurgence is simply unfeasible, whether the SCAF likes it or not.

[Image from unknown archive]

This is to say that authoritarian as we experienced it under Mubarak will likely be a thing of the past. At the same time, it is unrealistic to expect it to completely disappear in a matter of a few years or after a single round of elections. In fact, the next election, although will certainly fall short of bringing Egypt back to Mubarak-style authoritarianism, will likely reinforce the power of forces that dominated politics under Mubarak, including the Muslim Brotherhood, ex-NDP allies and traditional local forces.

Thus, the realization of the goals of this revolution is subject to a long marathon and not a short sprint. The challenges ahead are many and, as Brownlee remarked, are not limited to the electoral or constitutional sphere. For example, SCAF often says it is committed to handing over power to an elected civilian president early next year. It is likely, however, that the Council will adopt a policy of “All but the Army,” in managing its relations with the next president and parliament, seeking to keep the military’s budget and economic interests beyond the reach and oversight of elected officials. This will probably open up a long conflict over civilian control of military institutions, the outcome of which remains uncertain. Beyond the military, it is also expected that other Egyptian bureaucracies—not just the Ministry of Interior—will strongly resist efforts to introduce greater accountability and transparency to the Egyptian government.

The challenges ahead are numerous, but it is hard to argue that a return to an authoritarian status quo is one of them.

“Citizens and State in Post-Mubarak Egypt,” by Samer Shehata [open in separate window]

Jason Brownlee is correct to argue that the most daunting challenge facing efforts to advance democratic change in Egypt is not whether constitution writing should precede elections or choosing between different electoral systems, but security sector reform. Comprehensive reform of the security state—and specifically, the Ministry of Interior and its sub-organizations, the ‘bowels’ of Mubarak’s repressive state apparatus–is crucial if Egyptians are to establish a democratic society based on the rule of law.

Fraudulent elections were a regular feature of Mubarak’s Egypt. Mismanagement of government resources was rampant. Public education was left to deteriorate and health institutions were badly neglected. But more troubling to ordinary Egyptians was the daily abuse they suffered at the hands of the security services, especially the police, but also, the State Security Investigations Services (SSIS), and the Central Security Forces (CSF). Egypt under Mubarak was far from a state based on the rule of law. In fact, law enforcement agencies, the very institutions that should have been entrusted with upholding the law in public life and in their own practices, systematically abused their authority.[i] This became glaringly obvious to outside observers through high profile cases such as that of Emad El Kibeer and, more famously, Khaled Said, but it was, and remains, a regular feature of life in authoritarian Egypt.

Moreover, as both the Said and El Kibeer cases demonstrate, the problem extends well beyond “formal institutions.” The arbitrary exercise of power is pervasive, and extends to ordinary interactions between security personnel and “citizens”. Rather than serving the people, the security forces lord over the public, often treating Egyptians with little respect or dignity. In fact, many observers see in the ‘Arab Spring’ a struggle by ordinary people to restore their dignity after suffering arbitrary abuse at the hands of corrupt authorities.

The Ministry of Interior was the heavy, repressive boot of the Mubarak regime against the throat of the Egyptian people. It enjoys sweeping powers (i.e., the majority of current police officers have only worked under the Emergency Law, in effect since 1981) and significant material and human resources.[ii] Ensuring the regime’s survival, not protecting the citizenry or upholding the rule of law, was its primary function.

Absent was the understanding that the police and the security forces more generally, are not above the law or immune from accountability. In fact, Habib El-Adly, the despised former Minister of Interior now in custody awaiting trial, changed the police’s motto several years ago. The motto had long been -- somewhat ironically -- “the police in the service of the people.” Adly replaced this with an Orwellian-sounding slogan, “the police and the people in the service of the nation” (the old motto has since been readopted).

Abuse by security personnel took both small and large forms: in daily interactions with the police, on the street, at traffic stops, and police checkpoints, to more serious cases involving torture and human rights violations.[iii] The arbitrary exercise of authority was widespread. In the absence of any real accountability, security officials acted with near impunity. Suspected criminals were routinely mistreated, especially those accused of petty crimes. Heavy-handed techniques were the norm. Police stations were feared by many. Few rights or protections were afforded, especially to those without connections or money. And corruption was endemic.

Of course, the dehumanizing experience of suffering abuse at the hands of authorities that are unconstrained by the rule of law (everyday authoritarianism), was the corollary, and took place in parallel, to the “political” repression regularly carried out by uniformed security personnel, especially the CSF, and plain-clothes thugs (baltageyya) during elections, demonstrations, protests, and sit-ins.

[Central Security Forces face Egyptian Protesters. Image Source: M. Soli/ via wikimedia commons]

If Egypt’s “January 25 revolution” is to succeed, comprehensive security sector reform is essential. This extends well beyond the demand of holding those responsible for killing protesters during the revolution accountable. It means much more than rooting out officials who, in the past, carried out or authorized torture and human rights abuses. It must entail comprehensive reform of the Ministry of Interior, or “deconstructing the security state,” to borrow Brownlee’s felicitous phrase. The entire organization must be overhauled, from the police academy’s admissions procedures, to curricula and training, operating procedures, promotions, and the codes and norms governing the relationship between officers and conscripts. The organization’s ethos must be transformed into one that reflects a deep respect for the rule of law, the dignity of citizens, due process, accountability, and human rights. Accomplishing this will likely prove more difficult than holding “free and fair” elections or drafting a constitution.

Unfortunately, there is little indication that the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) or the current Minister of Interior is interested in undertaking such reforms.

What is to be done?

In addition to the changes outlined above, the Ministry of Interior must be placed under civilian control, as has already been suggested by a number of activists and civil society organizations. This could entail replacing the current minister (a basic demand of many of the July 8 protesters) with a civilian, preferably someone with a legal and human rights background. Reform must also entail drastically curtailing, if not eliminating, the role of the security services in many aspects of public, private, and political life. The Ministry of Interior’s (and particularly, the SSIS) surveillance and authority was pervasive and extended to universities (overseeing academic appointments, research, and student groups and activities), media whether private or state-owned, business,[iv] labor (through the state-controlled Egyptian Trade Union Federation), syndicates, and civil society groups, not to mention political parties, activists, Islamists, and elections. Even high-ranking government officials and ministers were, at times, the targets of security surveillance. So far, the SCAF has only changed the name of the SSIS and made promises of further reform. More recently, the government announced the dismissal of several hundred high ranking officers, and the commencement of trials against officers suspected of murdering protesters. None of these steps address the structural aspects of the problem at hand.

In addition to the measures outlined above, clearly established and effective institutional channels for citizen complaint must be put in place, to ensure accountability. Achieving greater transparency and oversight, particularly when it comes to budgetary matters, must be the guiding principles of any security sector reform initiative in Egypt.

The primary benefit of democratic governance is not the right to place a ballot in a ballot box every few years. It is to live in a society governed by the rule of law, and characterized by citizenship, accountability, and the protections of basic freedoms (both, of course, are related). The ballot box is one particularly important mechanism for establishing and preserving such a society. This reminder could not be more relevant to ongoing efforts to advance democratic change in Egypt.

“A Final Response,” by Jason Brownlee

Before reflecting briefly on my colleagues’ incisive remarks about post-Mubarak authoritarianism, I want to extend my deep thanks to Hesham Sallam for organizing this virtual round table and to the exceptionally qualified respondents who accepted his invitation.

Since the end of January I have often recalled the paradox of “unstoppable force meets immovable object.” The demonstrators were unstoppable; the regime immovable. Nearly six months after the Day of Rage, remarks in this forum underscore the continuing relevance of that image. As we all seem to agree, the clash (fortunately) has not broken decisively in favor of the military, crooked businessmen, and other erstwhile Mubarak clients. Moreover, if the Tahrir-centered activism of the past months continues to build, the dynamic may break in the other direction. Whichever way things go, the success of mass collective action to impose questions and solutions from the grassroots up represents a triumph for organizers and other citizens seeking social justice and accountable government.

With my respect to the specific points of my interlocutors, I wholly concur with Issandr El-Amrani that we should not buy into the argument of delaying elections for fear the “radicals” will win. The March 19 referendum was no defeat for democracy. (However, the SCAF’s later constitutional declaration turned the vote into Egypt’s freest and fairest fake election—a good process devoid of binding results.) Likewise, I share El-Amrani’s sober and upbeat assessment of Egyptians’ commitment to challenging the military and the state. The only actors who deserve “pessimism” are the elites on the opposing side of that struggle. Regarding Nathan Brown’s guarded cheer, my column was offered in the spirit of “worrying” about the Egyptian military without being less “happy” for what civilians are accomplishing.

There are other groups that should trigger vigilance. Zeinab Abul-Magd directs attention beyond the police and military to the exploitive economic networks on which they have depended. Following her point, those are of us not already doing so should interrogate the conservative (reactionary) alliance between corrupt tycoons and the Ministry of Defense, which may be reproduced while activists and academics are occupied with Tahrir.

Daniel Brumberg has done me (and all readers of this forum) a service in pointing to literature about reforming police states. For Egypt watchers who have not yet read it, Al Stepan’s classic on the demilitarization of Brazil (a lodestone these days), illumines the bureaucratic and political obstacles to that effort. More immediately, Samer Shehata provides a brilliant assessment of what specific measures could help end the security state and establish citizen sovereignty.

All of this boils down to the question, articulated by Mohamed El-Menshawy, of whether popular pressure will prevent an “authoritarian resurgence.” I certainly can imagine that possibility, but I question the expectation that authoritarian practices will ebb over time—as progressive forces win the “marathon” against incumbent elites. The case of Russia in the 1990s, with its alliance of neoliberal and security oligarchs, exhibits problems Abul-Magd and Al-Amrani mentioned, and underscores the risks of postponing structural reforms. The unstoppable force must not let up.

[i] Of course, this is perfectly understandable considering the authoritarian character of the regime. The Interior Ministry performed, as it should have, and largely according to plan, in such a system.

[ii] Estimates of the size of the Central Security Forces vary. Brownlee writes that the CSF numbered 300,000 while Samer Soliman estimates their strength at 450,000 See Samer Soliman, The Autumn of Dictatorship: Fiscal Crisis and Political Change in Egypt under Mubarak (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011) p. 63. Ibrahim Al Sahary writes that the force numbered between 300,000 and 400,000 in 1986, at the time of the CSF riots. See http://www.e-socialists.net/node/3390

[iii] For a recent cinematic rendition of the problem, see Yousef Chahine’s last film, Heya Fawda (It’s Chaos), about police corruption in a Cairo neighborhood. http://www.masrawy.com/News/Arts/elcinema/2011/April/6/4443845.aspx For incidents of police abuse after the “January 25 revolution,” see the episode of Baladna bil Masry entitled “Torture in Egypt before and after the January 25 Revolution.” http://www.ontveg.com/VideoDetails.aspx?MediaID=318374

[iv] According to these documents, SSIS made arrangements with a number of well known clothing companies to sell its employees merchandise at significant discounts: http://25leaks.com/documents/20