“The sidewalk was like a mirror

Now, a sanitation worker collects the bodies of dead people […]

My memories died yesterday

But a tree smiling in Abu Nuwas has enlivened them”

– Iraqi poet Fadhil Abbas.

This essay examines the ways in which the political circumstances of post-invasion Iraq have shaped the social and spatial realities of Baghdad’s key urban spaces, particularly Abu Nuwas Street. Since its American occupation in 2003, Baghdad has experienced securitization, sectarianism, and privatization undermining the public realm and restricting how people use their public spaces. Other cities in the region have experienced a similar urban situation. In Cairo, Egyptian governments since the time of Gamal Abdul Nasser have adopted a “state of emergency,” with the result that the city is transformed “into a battlefield, in which `national security` and the `war on terrorism` became justifications to control space and bodies” through state security apparatuses and interventions.[1] State-imposed physical security measures have, therefore, appeared: the Egyptian government during the presidency of Hosni Mubarak installed “metal walls” around major squares and sidewalks. These walls physically fragment the public realm of the city, restricting people’s movement and forcing them to “compete for space with cars.” The walls also resulted in the death of protesters during the January revolution who “found themselves trapped behind the walls and were beaten to death” by the security forces. Both during the revolution and afterward, the authorities erected blast walls around government buildings and closed off streets around Tahrir Square. Also, in Cairo, private destinations appropriate the riverbanks of the Nile. Security restrictions by government and private security agents, and lack of official planning efforts to enhance public access to the river, disconnect the public from one of the city’s main assets.[2]

In Beirut, the public realm is shrinking. After the end of the civil war in 1990, state “infrastructure-led urban development” resulted in “real-estate dividends” benefitting the “ruling elites and their partners.” Public access to the city’s seashore has suffered from a “private takeover” in the form of “enclosed, high-end resorts.” Recently, “prominent investors” have fenced-off the Dalieh (a seashore “open access shared space” facing the famous Pigeons’ Rock) “in preparation for a major real estate development.” Also, mobility of city dwellers is “circumscribed through installations of barriers, blockades, checkpoints and the rerouting of traffic flow” mainly to protect the political elites from a “criminalized and differentiated public.”[3] City dwellers modify their movement in relation to certain areas and neighborhoods of the city that they consider receptive (or not) with regard to class, gender, nationality, religion, and/or sect.[4]

The role of public space as a site contested between the people and the authorities has been all the more important in these cities. Protests are the tip of the iceberg. In Baghdad, recent demonstrations against the corruption of the political elites have taken place every Friday in al-Tahrir Square with protesters displaying banners and chanting slogans provocative to the ruling Islamist parties: “In the name of religion, thieves stole us.” In Beirut, too, activists have launched the "YouStink" Campaign, and the Martyrs’ Square in Beirut has been its main demonstration site. Before that, many of us witnessed on television and social media Egyptians protesting against Mubarak’s regime in Cairo’s Tahrir Square.

In order to answer the question I am raising in this essay, I begin by tracing the history of the street since its construction, focusing on the socio-spatial practices of its users. I show how and when the street gained its significant image, which has persisted until the present in the accounts of city dwellers. Also, I identify its decline, which started around the time Saddam Hussein became president, as a physical space used in ways related to its persistent image as a symbol of Baghdadi cultural and entertainment life in its height during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. I then go through the post-invasion (or “Post-Change” as some pro-invasion Iraqi intellectuals would like to call it) events, especially those having an impact on the urban spaces of the city in general and Abu Nuwas Street in particular.

Beginnings (1920s-1930s through 1968)

At the time of the construction of the street by the beginning of the 1930s, Baghdad had already been expanding beyond its old city, with new neighborhoods being established such as al-Wazeriya, al-Alwiya, al-Karrada al-Sharqiya, and al-Sa’doun. New types of buildings and facilities accompanied the expansion to fulfill the demands of the nascent state and society, such as airports, bridges, post offices, public-administration buildings, cinemas, and others. New urban elements were introduced, such as public gardens, green areas, and statues, and new laws passed, such as the Road and Building Law No. 44 of 1935.[5]

In continuation of its former status as a green place for the well-off and their summer residences,[6] the state-planned street maintained its upper-class characteristics. A road replaced the dyke along the bank of the Tigris. The remaining area adjacent to the river comprised a sidewalk and parks, whereas the other side of the street was a built-up area. The basic physical configuration of the street has not changed since its construction. Residents from various religious backgrounds (mainly Sunnis, Christians, and Jews) inhabited the upper part of the street close to the al-Bab al-Sharqi, al-Battaween, and al-Sa’doun areas, and Shi’i residents mostly inhabited the lower part close to al-Karrada.[7]

Abu Nuwas Street is an extension of the older, equally celebrated al-Rashid Street in terms of both their physical adjacency and the activities that took place there. If the cafés of al-Rashid Street were a haven for the intelligentsia during daytime then they spent their night on Abu Nuwas Street, drinking and eating masgouf (a Baghdadi delicacy of coal-grilled carp). They spent the evening in chirdagh (a tent on the sand swathes of the river) listening to music, drinking alcohol, and grilling.[8] Families, on the other hand, frequented casinos (not gambling places, but restaurants with occasional entertainment shows) mainly to eat masgouf, attend entertainment shows, and/or enjoy the presence of the river.[9] People crowded the open public spaces of the street, and the parks too. During the 1950s, the street, including its parks, casinos, and chirdagh, became an essential, leisurely destination for city dwellers and its image was strongly associated with the aforementioned leisurely activities.[10]

The Street under Ba’athist Rule (1968-2003)

After the 17 July 1968 coup, the ruling Ba’th Party became increasingly concerned with security. The area of the Republican Palace across the river from Abu Nuwas Street became heavily policed as officials–including the then president and vice president, Ahmad Hassan al-Bakr and Saddam Hussein respectively–resided in the area, making it more visible for the city dwellers as the regime’s headquarters. In spite of restrictions on civil liberties and political dissent, the 1970s marked a bright juncture in the street’s life for many Baghdadis. People continued to frequent the riverside casinos. In the publicly accessible strip of green areas along the river, individuals, couples, and families used the playgrounds and benches. Men hopped in and out of the bars along the other side of the street, which was more active in the evening than daytime.

By the end of the 1970s and beginning of the 1980s, the state carried out major projects across the city including two luxurious hotels (Ishtar and Palestine) and a residential project on the street. These projects aimed at reviving an “Arab and Mesopotamian grandeur” for the capital city under Saddam Hussein’s rule.[11] Also, the regime’s headquarters across the river consolidated their periphery by resettling loyal occupants (senior staff of the presidential palace) in the street’s residential project,[12] resulting in the demolition of many modern heritage buildings dating back to the 1930s and 1940s.[13]

The late 1970s and the 1980s mark the beginning of the gradual descent of the “golden days” of Abu Nuwas Street, due to rising police practices of a totalitarian state ruled by Saddam Hussein. “Then came the Iraq-Iran War isolating the street from many of its devoted goers … a list of prohibitions then was imposed,” the Iraqi journalist Baida’ Kareem wrote, “starting with no boating zones, no floating casinos, etc., and other measures controlling practices on land (no partying) and in water (no swimming to the other bank across the street).”[14] By then, the chirdagh had completely disappeared due to the state’s security restrictions. Moreover, in 1994, the state banned alcohol drinking in the street’s casinos, restaurants, and hotels after it launched “al-hamla al-imaniyya” ("The Faith Campaign"). As a result, alcohol drinking, which had been a main spatial practice for many street users, virtually disappeared, although some users defied the ban secretly. “The street died in the 1990s,” Baida’ Kareem states.

Occupation and Sectarian Violence: The Securitization of Urban Spaces and Sectarian-based Reordering of the City (2003-2007)

Shortly after the occupation of Iraq had begun, violence in Baghdad escalated until the many hotels where Westerners and officials resided, both on Abu Nuwas Street and elsewhere, became a target for the armed resistance. The occupation forces responded by erecting blast walls and razor wire to barricade the hotels, and by closing off the segment of the street where the hotels are located. Checkpoints guarded either end of the closed-off segment. At the same time, the Ba’thist regime’s quarters across the river became a US-fortified zone famously known as the Green Zone. The perception of the quarters changed too. One Iraqi boy put it this way: “Saddam house … Now, Bush house.” Moreover, the occupation forces restricted access to the street’s riverbank “lest militants use it to mount attacks on the Green Zone.” In the meantime, the street is still rife with physical security measures constraining people’s practices and movement and preventing them from accessing the river.[15] One Iraqi expressed that Abu-Nuwas turned into “a street for the security forces.”

The occupation authority (the Coalition Provisional Authority led by Paul Bremer) enforced political interventions, which reproduced the sectarian-based inequalities that had existed before the occupation, with dire repercussions on the everyday life of city dwellers. The favoritism toward Sunnis who dominated the high ranks of the pre-invasion Iraqi state disappeared, and a new political power relation ensued in favor of the Shi`i political parties.[16] The Ba’athist regime had manipulated ethnic and sectarian differences to control rebelling segments of the Iraqi population “in moments of crisis” such as the 1991 Shi`i uprising.[17] As Damluji clarifies, “Hussein’s national policies did promote differential treatment of Iraqis based on ethno-sectarian identities, with visible impacts on the socio-economic and political status of some Shi’as living in the capital.” But, she continues, “Sunnis and Shi’as in the city continued to reside, socialize, and work in heterogeneous communities and neighborhoods as had historically been the case.”[18] However, during the occupation, and more precisely in the wake of the bombing of the holy Shi’i al-Askari shrine in February 2006, Baghdad went through a sectarian-based demographic reordering in the form of a forced displacement campaign. Hence, the many previously mixed neighborhoods were homogenized into either Sunni or Shi’i.

The CPA, headed by Bremer, executed a policy of “de-Ba’thification” of Iraqi society, including the dismantlement of all pre-invasion government entities, among them the ministries and security forces. These orders resulted in the disenfranchisement and political marginalization of many Sunnis who had held official posts before the occupation. The support of disaffected Sunnis for the Iraqi armed resistance increased. In July 2003, the CPA established the Interim Governing Council through an undemocratic process that involved no consultation with a broad spectrum of Iraqi political parties or local community leaders. Members were appointed to the council according to predetermined quotas, categorizing Iraqis along ethnic and sectarian lines and hence reinforcing the role these identities have played in post-invasion politics. The elections to the transitional National Assembly of Iraq, which took place in early 2005, replicated the same differentiations. The assembly was responsible for the establishment of a permanent Iraqi constitution and transitional government. A constitutional committee hastily drafted a constitution under pressure from the United States despite the withdrawal of the Sunni Arab representatives from the committee and the lack of consensus among the parties involved. On the other hand, the Shi’i political parties dominated the transitional government. The Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), through its armed militia the Badr Brigade, controlled the Ministry of Interior, and CPA Order No. 91 encouraged its members to enlist in the newly formed Iraqi police. By 2005, al-Qa`ida began targeting not only government forces, largely constituted by Shi’ia, but also Shi’i civilians. Both Shi’i and Sunni warring parties “identified vulnerable communities, families, and individual civilian residents in Baghdad according to sectarian identity, and transformed them into targets for politically driven retaliation attacks”.[19] Shortly after the bombing of the Shi`i shrine in 2006, the strife between Sunni militas and Shi`i militias supported by government forces escalated, reaching levels unprecedented in the preceding years of the occupation. This included mass forced displacement of residents of hitherto mixed neighborhoods, which eventually turned into homogeneous settlements. Sectarian violence decreased once many neighborhoods became homogenized, as Shi`i militias consolidated their enormous territorial gains,[20] as well as due to the US “surge” military strategy and the incorporation of previously anti-government and anti-occupation Sunni fighters into the so-called “awakening councils”.[21] The civil strife ended–or stalled–with the Shi`i political organizations gaining ascendancy in the “political conflict over the right to rule Iraq, to share its resources and to define the meaning of the nationalist projects.”[22] Thereafter, the occupation forces implemented a plan to erect perimeter blast walls around Sunni and Shi`i neighborhoods, further hardening segregation lines and exacerbating the already-restricted mobility of city dwellers.[23]

In August 2009, the Iraqi government decided to lift the walls from all the closed-off streets in Baghdad “without exception” within forty days. This ambitious plan (or, political charade?) never took place, but the government did remove the walls from some commercial areas in central Baghdad to mitigate traffic congestion and facilitate better commercial activity for shops that the walls had isolated. In 2011, the Mayoralty of Baghdad declared that it had “prepared a plan to lift concrete barriers from all areas in the city,” and the official military spokesman of the Baghdad Operation Command had declared a similar plan earlier that year. Concurrently, the government lifted the walls from the Shi`i al-Sadr City in Baghdad because, according to the same military spokesman, “the City witnessed security stability and considerable collaboration on the part of the community with the security apparatuses.”

In the meantime, restrictions on mobility still take on a sectarian dimension, although it is less intense than that which resulted from the 2005-2007 sectarian violence. Residents of the Sunni neighborhoods, such as al-Adhamiya and al-Ghazaliya, feel unjust treatment by the government because their neighborhoods are still walled in a dominantly Shi`i city. Getting in and out of the walled Sunni neighborhoods through checkpoints controlled by dominantly Shi`i personnel potentially entails inconvenience and intimidation. Consequently, Sunni neighborhoods have become an undesirable location to live in.[24] During Shi`i rituals (i.e. the Mourning of Muharram and the Day of Ashura) or occasions of heightened political and security tension, restrictions get tighter.

With regard to Abu Nuwas Street, the area where it is located turned into a predominantly Shi`i area in 2006.[25] Mostly low-income Shi`i families squatted the residential buildings as the former occupants fled for fear of retaliation. Flags, banners, and posters conveying Shi`i messages and symbols appeared in the post-invasion city as Shi`i residents could not display such signs under the Ba’thist rule.

[Banners on the fence of a squatted residence in the southern section of Abu Nuwas Street, with inscriptions of “ya Hussein." Another hung on the building’s façade over the entrance inscribed with “ya Abbas.” Photo by Author].

The Reopening and “Redevelopment” of Abu Nuwas Street and Parks (2007-2012)

In November 2007, the occupation forces, in collaboration with the Iraqi government, reopened the closed-off segments of Abu Nuwas Street and its parks. The US military and USAID provided a two-million-dollar fund to implement a “facelift” of buildings through Iraqi subcontractors. Shop owners received 2,500-dollar micro-grants. The renovation also entailed furnishing the parks with grass areas, footbridges, swings and benches. Several months after its reopening, the street’s parks were receiving a large number of visitors: young men smoking hookah or sitting on the benches; children playing in the playgrounds while escorted by their parents; and people eating masgouf in the restaurants.[26]

[Two girls playing in the swings in the large park of Abu Nuwas Street in January 2014. Photo by Author.]

In November 2012, the mayoralty of Baghdad launched a redevelopment project for the street which entailed the demolition of “some restaurants and cafés” and the construction of “a service and tourist [riverside] street and another for bicycles in the middle of the gardens.” The mayoralty constructed the two streets inside the park.[27] Some restaurants in the park were also demolished as they “were used in a wrong way” according to an official of the mayoralty, possibly referring to alcohol drinking and prostitution. The Iraqi owner of a carpentry workshop also perceived one of the demolished restaurants in the northern section of the park as a place that housed “improper activities.”[28]

Proliferation of Pseudo-Public Spaces in the City, and Proposed “Investment Projects” on Abu Nuwas Street

In the past few years, there has been a proliferation of pseudo-public destinations in Baghdad–namely, malls and restaurants/cafés. Also, many residential high-rise buildings in the form of housing complexes are under construction at the moment. The Baghdad Investment Commission is the authority responsible for issuing “investment licenses” for and coordinating with investors developing these projects.

The transition from a “centralized economy” to a “market economy” after the invasion, which both chairmen of the National Investment Commission and the Baghdad Investment Commission state as a fact, has opened the Iraqi real estate market for privatization by local and foreign investors. Efforts toward this transition started when Bremer’s CPA imposed “economic reforms” so radical that The Economist described them as a “kind of wish-list that foreign investors and donor agencies dream of for developing markets.” The CPA, through Order No. 37, set “individual and corporate income” taxes at fifteen percent maximum. Its Order No. 39 allowed foreign investors one hundred percent ownership of Iraqi assets and repatriation of profits, and permitted foreign investment “in all parts of Iraq” and all economic sectors except the natural resources sector. It also prohibited foreign investors from purchasing “the rights of disposal and usufruct private real property” but permitted them to lease or rent properties for no more than forty years. This order, nevertheless, did not take effect. Regardless, the obligations set by the Paris Club in 2004 to substantially relieve Iraq from its enormous debts required the implementation of an IMF Emergency Post-Conflict Assistance Program. One of the program’s main “underpinnings” is “the implementation of key structural reforms to transform Iraq into a market economy.” The IMF expressed in 2005 that the implementation of these “structural benchmarks” is “slower than envisaged” due to security. It stated, nonetheless, that the government’s 2006 program still “maintains a focus on macroeconomic stability, while … advancing Iraq`s transition to a market economy.” In the same year, the Iraqi Council of Representatives approved the Investment Law No. 13 (amended in 2010) which repealed CPA Order No. 39. The law itself is no different from the occupation authority’s order, except that now the duration of rent or lease is fifty years maximum instead of forty, and Iraqi and foreign investors are permitted to own lands for the purpose of developing housing projects only. The law also stipulated the establishment of “national," “region’s” (if applicable), and “governorate” commissions for investment.

By December 2014, Baghdad Investment Commission had issued investment licenses for seventy “giant residential projects,” which will provide one hundred thirty thousand residential units, and sixty licenses for “touristic projects.” The commission announced that the residential projects will “contribute to solving the housing crisis which has exacerbated recently,” and that the “touristic projects” aim to compensate for “the lack of touristic and hotel services” in the city. It claims that these projects “fulfill the needs of citizens, who are seeking comfort, recreation, entertainment, and shopping.” The commission, furthermore, conceives of “the phenomenon of commercial malls, which has been spreading,” as “a civilized aspect reflecting contemporary sensibility and urban development.” It ascribes the “widespread proliferation of such commercial malls” to its efforts.

Several malls have opened in the city: most notable are Mansour Mall and Maximall. Several large restaurants have also opened, including four riverside restaurants. Two of the latter are “floating restaurants” located on the street which is also officially called Abu Nuwas and was once the extension of Abu Nuwas Street discussed in this essay.[29] The other two are large restaurants/cafés composed of many gardens, halls, and riverside areas.

The dire security situation, as one manager of a mall expressed, demands searching people entering it. An Iraqi woman shared the same fear saying, “when [Mansour Mall] first opened … We worried that if someone blew up a bomb, there would be a massacre." Some managers expressed that the “safety” of such places vis-a-vis the “unsafety” of the city’s open public spaces is the reason why people choose to hang out there for leisure and/or shopping. Another Iraqi woman concurred, saying: “I can watch my kids playing safely and get whatever I need in the stores.” Yet another woman noted that “malls have not witnessed incidents of harassment of women and girls because most of their goers are families.” However, according to an Iraqi women’s rights activist, “the phenomenon [of sexual harassment of women] is increasing exponentially in public spaces such as gardens and parks."

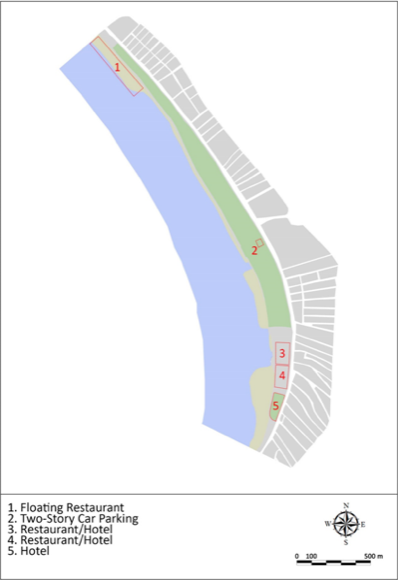

In the first half of 2014, the mayoralty of Baghdad, through its investment committee, considered a plan to designate five locations for investment in the riverside part of the street (see map below).[30] Two of these projects seem to have serious repercussions on the public space of the street in case they are implemented: the “floating restaurant” in the northern part of the large park; and the hotel in the whole location of the small park. Such privatization, if it is to take place, will erase important parts of a city with the few remaining riverside public spaces, and could potentially affect the adjacent park areas and the ways in which people currently use them. Men of various age groups use the northern section of the large park mainly for alcohol drinking, despite the inconvenience of prevalent moral codes and occasional raids by the police.[31] Activist groups and other–especially young–groups of men and women use the small park for cultural and entertainment events.[32]

[Location map of the proposed investment projects. Map by Author.]

Parallels between Past and Present, and the Introduction of New Urban Realities

As is evident in one of the main open public spaces of the city, restrictions on the socio-spatial practices of street users, which resulted from the policing of space by the Ba’thist regime until 2003, reappeared during the US occupation. Since 2003, very noticeable forms of securitization have existed, resulting in the same old restrictions as well as some new ones. City dwellers are still unable to access the river from Abu Nuwas Street for security reasons–namely, guaranteeing the safety of the fortified Green Zone across the river, a reason identical to that of the Ba’thist regime. Alcohol drinking is another case in point. As a result of the Faith Campaign, the state banned it, and people did it secretly. A rather similar situation is present today. The mayoralty invoked the immorality of alcohol drinking as one of the reasons behind its decision to demolish some restaurants in 2012. Now this practice does not take place in restaurants. Rather, men of various age groups cautiously practice it in the northern part of the large park, despite security and moral constraints.

What makes the security situation direr still is the sectarian landscape of the post-invasion city. This reality is a recent one, which came along with the occupation as a direct result of its political interventions, as demonstrated above. The constraining impacts of securitization of public space unequally affect city dwellers. In general, Sunnis have less leverage in negotiating their right to use and appropriate space. On Abu Nuwas Street, like elsewhere in the city, territory marking takes place along sectarian lines. Flags and banners conveying Shi`i signs and messages exclude other markings on the street (i.e. Sunni markings).[33]

Despite these restrictive conditions, street users crafted opportunities from below, circumventing the security measures and making the public spaces in the street suitable for their purposes. They appropriate these places through everyday spatial practices, using tactics to lessen the dire effects of security and sectarian measures.[34] Activists, too, have striven to show an image of Baghdad different from that circulated in the media and related to war and violence by holding public events. These collective events (most famous is the “I am Iraqi, I Read” event) aim to convey messages related to love, peace, and/or simply having fun.[35]

Therefore, public space in Abu Nuwas Street is contested. The aforementioned public events implicitly counter the political sectarianism and religious extremism ingrained in the reality of post-invasion Iraq.[36] For example, although perceptions of the Colors Festival (held in March 2015 in the small park of Abu Nuwas Street) varied, some perceived it as being “morally disgusting” or as an act of “on-air prostitution,” “public and explicit insolence,” and others. The governor of Karbala said, commenting on the possibility of holding a similar event in the Shi`i holy city, “such an event is not innocent, and its purpose is to spoil the youth and waste their energies through imported practices.” References to the ongoing war with ISIS usually accompany such derogatory comments to highlight the “inappropriateness” of the timing and content of such events.

Although the leisurely socio-spatial practices that took place in the street in the 1950s-1970s era are no longer found today, perceptions about the street are still very much linked to that era. Many people celebrate the street as one for delight and enjoyment devoid of religious and/or sectarian associations and commercial imperatives. But this very celebration has made the street, as Pieri put it, a “contested window”[37] in the late-1970s major (re)development projects as well as the recent investment plan. Tapping into the already-significant symbolism of the street, as well as its location across the river from its headquarters, the Ba’thist regime implemented a number of major developments there. With regard to the recently proposed investment projects, whether these materialize the state’s need to control the practices in the parks’ public spaces, especially those that it perceives to be immoral such as alcohol-drinking or public events, and/or whether economic interests drive them, requires further investigation. In any case, they attest to the absence of any participatory planning practice sponsored by the pre- or post-invasion state. Hence, the absence of a meaningful democratic participation of city dwellers in planning one of the few remaining on-river open public spaces accessible to them. The decision whether or not to implement these projects is left exclusively to the mayor,[38] who, despite public scrutiny–which would arise if they are implemented–can take the final decision.

Furthermore, the 2006 investment law has unleashed what appears to be a huge campaign of privatization, defined as the provision of destinations for a select public by private agents. These destinations are privately-owned-and-administered spaces of consumption and “aggregation”–most commonly, malls–where the ability to purchase governs access, and where private security ensures predictability, regularity, and orderliness of users and their behaviors to ensure the “flow of commerce.”[39] In Baghdad, similar spaces offer a safer alternative to the traditional spaces of shopping, such as commercial streets, and recreation, such as parks, characterized by what seems to be an endemic lack of security. They also provide a more comfortable haven for women, who frequently suffer sexual harassment in the public spaces of the city. But, as Caldeira shows in the case of São Paulo, the proliferation of “fortified enclaves” creates a new model of spatial segregation, and transforms the quality of life, openness and free circulation, character of public space, and citizens’ participation.[40] In the case of Baghdad, it would be interesting to investigate whether the increasing number of privatized spaces for residence, consumption, leisure, and work is forming another layer of class segregation in addition to the sectarian-based segregation already in place.

[The main body of this essay is extracted from my master’s thesis entitled Consolidating Socio-Spatial Practices in a Militarized Public Space: The Case of Abu Nuwas Street in Baghdad, which I submitted in September 2014 for the degree of Master of Urban Planning and Policy at the American University of Beirut. I would like to acknowledge the input of my thesis advisor Mona Harb, and of my thesis readers Ahmad Gharbieh and Caecilia Pieri. I would also like to thank Jadaliyya’s Cities Page Editors for their useful comments.]

------------------------------------------------------

[1] Salma Abdouelhossein, “Urbanism of Exception: Reflection on Cairo’s Long Lasting State of Emergency and its Spatial Production” (paper presented at the RC21 International Conference on The Ideal City: between myth and reality. Representations, policies, contradictions and challenges for tomorrow’s urban life, Urbino (Italy), 27-29 August, 2015). Accessed at http://www.rc21.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/D2-Abouelhossein.pdf on October 12, 2015.

[2] Kondolf G.M. et. al., “Connecting Cairo to the Nile: Renewing life and heritage on the river” (IURD Working Paper No. WP-2011-06. Department of Landscape Architecture & Environmental Planning, University of California, Berkeley, 2011). Accessed at http://ced.berkeley.edu/~cairo/CairoFinalReport.pdf on October 10 2015.

[3] Kristin V. Monroe, “Being Mobile in Beirut,” City & Society, 23, no. 1 (2011), 91-111.

[4] Mona Fawaz, Mona Harb, and Ahmad Gharbieh, “Living Beirut`s Security Zones: An Investigation of the Modalities and Practice of Urban Security,” City & Society, 24, no. 2 (2012), 173-195.

[5] Khalid al-Sultani, “Ru’ā Mi‘māriya” (Arabic) (Arab Institute for Research and Publishing, 2000).

[6] Abd al-Razzaq al-Hassani, “al-‘Irāq Qadīman wa Ḥadīthan” (Arabic) (Saida: Maṭba‘at al-‘Irfān, 1958), 108.[7] Caecilia Pieri’s remarks for the author (February, 2014).

[8] “أبو نؤاس شارع السمك يقضي الليل وحيداً حالماً بالفرح,” Almada Newspaper, May 18 2012.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Abd al-Razzaq al-Hassani, “al-‘Irāq Qadīman wa Ḥadīthan,” 105.

[11] Caecilia Pieri, “Modernity and its Posts in Constructing an Arab Capital: Baghdad’s Urban Space and Architecture,” Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 42, no. 1-2 (2008), 32-42.

[12] “Abu Nawas Development Project,” ArchNet (source: AKTC). Accessed at http://archnet.org/library/sites/one-site.jsp?site_id=701 on August 31 2013.

[13] Caecilia Pieri, “Sites of Conflict: Baghdad’s Suspended Modernities versus a Fragmented Reality,” in Re-Conceptualizing Boundaries: Urban Design in the Arab World, edited by Robert Saliba (Ashgate, 2015): 199-212.

[14] Baida’ Kareem “أبو نواس: تاريخ في شارع,” Aljadidah News Network, April 19 2009. Accessed at http://aljadidah.com/2009/04/6460/ on August 31 2013.

[15] Yaseen Raad, “Diverse Socio-Spatial Practices in a Militarized Public Space: The Case of Abu Nuwas Street in Baghdad” (paper presented at a conference entitled Radical Increments: Toward New Platforms of Engaging Iraqi Studies, and organized by Muhsin al-Musawi and Yasmeen Hanoosh, Columbia University, April 21-24, 2015).

[16] Mona Damluji, “Securing Democracy in Iraq: Sectarian Politics and Segregation in Baghdad,” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 21, no. 2 (2010), 71-87.

[17] Derek Gregory, “The Biopolitics of Baghdad: Counterinsurgency and the Counter-City,” Human Geography 1, (2008), 6-27.

[18] Mona Damluji, “Securing Democracy in Iraq: Sectarian Politics and Segregation in Baghdad.”

[19] Ibid; it should be noted that Damluji’s work cited here has been key to my understanding of the political events and their impacts on the urban reality of post-invasion Baghdad.

[20] Derek Gregory, “The Biopolitics of Baghdad: Counterinsurgency and the Counter-City.”

[21] The “surge” –officially known as the New Way Forward and declared by Bush in January 2007– has two characteristics different from the one preceding it, Operation Together Forward. The first is the considerable increase in troops (deploying extra 20,000 troops mainly in Baghdad), and the second is the incorporation of the “new counterinsurgency doctrine”. Such doctrine “defines the population as the center of gravity of military operations” (Ibid.). It also aims at prioritizing cultural awareness of American soldiers in relation to the context they operate in, in contrast to the previous counterinsurgency strategy that focused on tactical issues -smart bombs, unmanned vehicles, etc. (ibid.).

[22] Ibid.

[23] Mona Damluji, “Securing Democracy in Iraq: Sectarian Politics and Segregation in Baghdad.”

[24] A taxi driver in Baghdad told me that “no one wants to buy a home in Sunni neighborhoods nowadays” pointing out that living there is inconvenient due to the high security measures in place.

[25] Also see: Joel Wing, “Columbia University Charts Sectarian Cleansing of Baghdad,” Musings on Iraq, November 19 2009. Accessed at http://musingsoniraq.blogspot.com/2009/11/blog-post.html (on September 2013). Check the strip of Abu Nuwas Street in the Baghdad 2006 map and how it turned into a Shi`ite area while the rest of the al-Karrada district was mixed.

[26] “شارع أبو نؤاس يستعيد المقاهي والمطاعم,” Al-Shorfa.com. April 1 2008. Accessed at http://mawtani.al-shorfa.com/ar/articles/iii/features/2008/04/01/feature-03 on April 30, 2014.

[27] It should be noted that the streets are not for public vehicular access. Rather, they are service roads used by garbage-collection trucks and military vehicles. Also, park users walk on them especially the one in the middle.

[28] Interview conducted by the author with an owner of a carpentry workshop in the northern part of the street (January, 2014).

[29] For photos, see the Facebook page of the Jadriya Floating Restaurant. Accessed at https://www.facebook.com/JadriyaRest/photos/pb.240773886105361.-2207520000.1445192845./250785498437533/?type=3&theater on October 18 2015.

[30] An official document reviewed by the author in June, 2014 at the Directorate of Design of the Mayoralty of Baghdad.

[31] Yaseen Raad, “Diverse Socio-Spatial Practices in a Militarized Public Space: The Case of Abu Nuwas Street in Baghdad.”

[32] Yaseen Raad, “The Production of an Alternative Image through Public Space,” in Logics of Space in the Middle East Today, edited by Mohamed Elshahed and Mona Damluji (Cairobserver, 2015): 24-25.

[33] Yaseen Raad, “Diverse Socio-Spatial Practices in a Militarized Public Space: The Case of Abu Nuwas Street in Baghdad.”

[34] Ibid.

[35] Yaseen Raad, “The Production of an Alternative Image through Public Space.”

[36] Ibid.

[37] Caecilia Pieri’s remarks for the author (September, 2014).

[38] An interview with employees of the Directorate of Design of the Mayoralty of Baghdad (June, 2014).

[39] Steven Flusty, “Building Paranoia,” in Architecture of Fear, edited by Nan Ellin (Princeton Architectural Press, 1997): 47-60.

[40] Teresa P. R. Caldeira, City of Walls: Crime, Segregation, and Citizenship in São Paulo (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000).