[This is the tenth installment of Amal Hanano`s diary of her trip back to Aleppo. You can read previous posts here.]

My name is not Amal Hanano.

Before you even think Amina Abdallah, I assure you I am a real person, a Syrian-American from Aleppo who was physically in the city this summer, writing under a pseudonym. Of course, the pseudonym turned out to have its own issues which I will address, but first, a story...

In the early decades of the last century, when certain events were unfolding as breaking news, only to become the fateful history that defines us today, there was an ancient land on a fluid map. A European country, riding the colonialist wave, decided it would like to occupy this land, like many empires before it since the beginning of time, and so it did. But, the era of empires from Roman to Ottoman had ended; this was the age of modernity, of nationalism, and a few brave men decided their people had suffered enough under foreign rule and oppression. They decided to rise up, united as Arabs, as Syrians. One of those men was from the great city of Aleppo. His name was Ibrahim Hanano.

He was born in 1869, in Kafar Takharim, a village west of Aleppo, the fertile land where olive and pistachio trees flourish in alternating groves. After graduating from high school in Aleppo, he studied law in Istanbul. He was tall and thin, with delicate, noble features. Like most intellectual Syrians at the time, who balanced tradition and modernity, he wore tailored western suits and a maroon tarbosh, fez, on his head.

When the French occupied Antioch (still Syrian, not yet Turkish), Hanano coordinated small bands of strong, agile rebels to defend his country. He believed Arabism would save Syria from colonialism, so under the banner of nationalism, he led the northern resistance, uniting Aleppo, Idleb, and Antioch. Hanano even convinced the elite society of Aleppo to embrace Arabism and join the revolts as well. After the French entered Damascus, then Aleppo, he formed a base in Jabal al-Zawiyeh, between Aleppo and Hama.

Hanano rejected France’s sectarian division of Greater Syria into six separate states: Damascus, Aleppo, Alawites, Jabal Druze, Sanjak of Alexandretta, and the State of Greater Lebanon (later, becoming the modern country of Lebanon). The original anti-hiwar, anti-dialogue opposition leader, Hanano rejected all negotiations with the French. No compromise was acceptable, he had only one demand: Syrian independence. He launched attacks and fought dozens of fierce battles, and his fallen rebels’ blood soaked the soil, the same soil that is blood-soaked once again in Hama, in Idleb, in Jabal al-Zawiya. Maybe our history of blood seeping into the roots of trees inflicted our prized washna cherries with the sourness found nowhere else in the world, the sourness of sorrows.

In 1925, under the leadership of Sultan Pasha al-Atrash, Hanano along with Shukri al-Quwatli, Hasan Al-Kharratt, Nasib al-Bakri, Fawzi Qawoqji, and many others, ignited al-Thawra al-Suriyyeh al-Kubra, The Great Syrian Revolt, of 1925, still considered to be a model for revolutions in the Middle East. Although the revolt ultimately failed to end the occupation, it planted seeds of nationalism and resistance, the tools which would eventually topple the French Mandate on Independence Day, April 17, 1946.

Hanano died in 1935, before his mission was complete, but not before he had set it on the right path. Ten years later, his close friend and partner in the resistance, Sa’ad Allah al-Jabri, was buried next to him, in the famous Aleppo cemetery named after al-za’im, the leader Ibrahim Hanano.

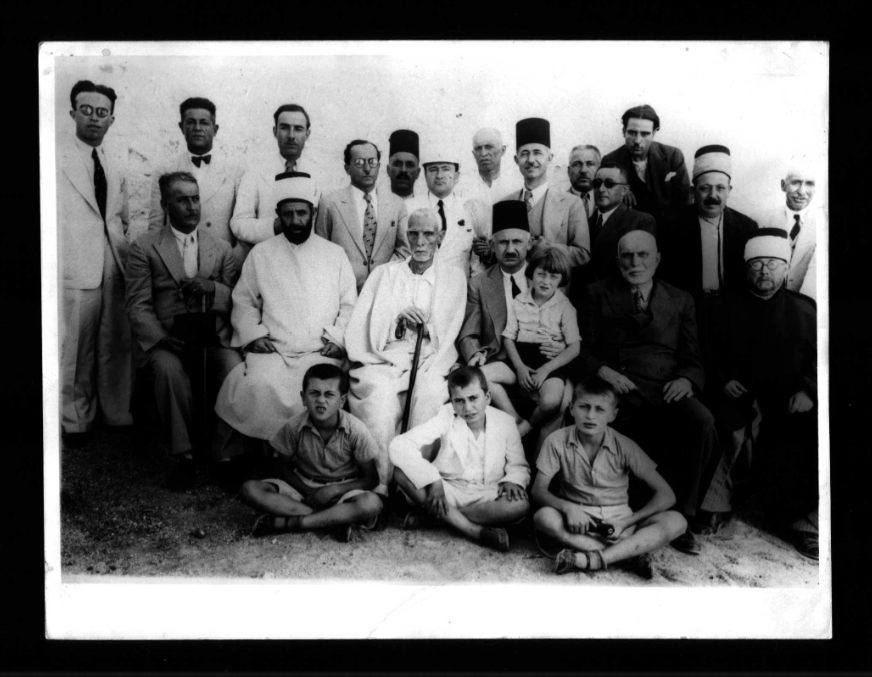

In my picture, he is white-haired, white-robed, cane in his hand, surrounded by loyal friends, a timeless symbol of wisdom and courage. I wonder, what Ibrahim Hanano or the other Syrian revolutionaries would say if they could see us now, after they sacrificed so much so we could live free of foreign occupation, only to be crushed by home-grown oppression? What would they say if they heard of the sectarian splits tearing our society apart, if they watched us believing the lies foreigners told us about ourselves, only today, those false claims are coming from the Syrian government? Would they regret fighting for us, sitting in prison cells for us, some of them dying for us? Would they even recognize us? Would they think that we, their descendants, were worth their sacrifice?

These heroes who shaped our history are constantly on my mind, as old questions and doubts about who we were and who we have become, haunt me. How did we let it come to this? Why did so many of us stay silent so long? Why did it take five other revolutions to spark our own? How could the Hama massacre of 1982, twenty-nine years ago, not have sparked our Syrian revolution? How did we let thousands of innocent people suffer in jail, while we turned a blind eye, in the name of living in “peace” and “security”? How did we grant the tyrant Hafez al-Assad a dignified death, buried him like a national hero in a marble grave, while his unqualified son slipped onto his father’s throne and millions cried crocodile tears? How did we let a corrupt regime suck our country dry, while we waved flags and cheered? Why is Syria the only country in the region that allowed the son to inherit his father’s place? Egypt and Libya were fighting this spring because they were not willing to let that scenario become their countries’ reality. Our revolution, is at best, eleven years too late.

I imagine these Syrian heroes would be as compassionate now as they were then, that they would embrace us and forgive our mistakes and our silence. I imagine Ibrahim would tell us, now is the time to rise up and start again, that this is our second chance, our hope. That we are his hope, his amal.

Hanano’s name was the badge of honor that I chose to represent Aleppo, Amal was just supposed to be his namesake, but she became much more.

I knew what I wanted to write about, and I had a choice, to disguise my story, bury it in ambiguity until it became untraceable, and thus meaningless, or tell the truth, in detail, with no fear, but not under my name to protect myself and my family. The most difficult part of this process, was the importance of speaking the truth, my truth, but starting it with something false.

I had a list of potential names, and agonized over the perfect one. Amal almost didn’t make the cut, just because there is probably a real Amal Hanano out there. (Dear real Amal, if you are reading, I pray the Syrian Electronic Army never knocks on your door, and if they do, direct them to this post.) But I emailed the first entry before remembering to change the name. So Amal, she stayed, by lucky accident.

Innama al-a`mal bil-niyyat, deeds are judged by their intention. Your intention changes your experience, and so for better or worse, the intention of documentation changed my perspective. Amal, in my mind, was me but slightly separate. She sat invisible, perched on my shoulder while I went about my daily life. She took mental notes, she was a third eye directing my camera lens towards shots I knew I would need later, she was always contextualizing the scene in front of me, remembering snippets of significant dialogue and sequences of events that I would jot down as soon as I was alone in my room. This split worried me; between what I needed to keep my writing honest and authentic and what needed to be left out to avoid betrayal (which I am not sure I did).

She was like a magic cloak, protecting me while filtering what I witnessed into what I would write. Some experiences (like going to the flag demonstration, or reaching out to the friend I had never met before, or taking most of my photographs) were ones I never would have had the courage to do without Amal. When I became Amal, it was like looking at your reflection in the mirror and seeing only the things you wish to see, only the good parts.

Amal’s story is not my entire story. She saw everything through a red lens of revolution. But I was surrounded by the sounds and scents of my city, the dry desert heat, walking at night between fragrant jasmine blossoms when I left my grandmother’s house, awaking to the sound of the morning adhan, call to prayer, from my bedroom, watching my friends’ children growing older, almost as old as we were when we became friends, tasting dishes that never change, but always delight. The city is the citadel at sunset, it is turning a corner and knowing that a specific minaret will appear exactly in the middle of your perspective. It is bending down to face a child on the street who curiously watches me taking pictures of posters and asks me to take her picture, asking me to see her, and I did. Those moments and countless more, some weave into my memories and dreams, and others already forgotten, those moments were mine and not Amal’s. That Aleppo is mine alone.

Amal gave me a voice I thought I had lost, and her ways began to rub off on me. My personal fear barrier still existed but was seriously breached. I ask my brother, “What happens if someone asks, ‘Are you Amal?’” He looks at me like it is the dumbest question in the world. “You say no. You have a pseudonym for a reason.” He is right, but sometimes, in moments of false courage, it was easy to forget why the false name was ever needed. And other times it was extremely clear, as I heard horror stories of parents in Syria being attacked for their children’s actions in the United States. And the fear looms large, concrete once again.

In the end I wrote for myself, to remember a time I knew would be like no other. What I did not anticipate was my joy when I read your comments to her, or my pain when I responded in her name to your names both real and concealed. I could not help but feel a pang of jealousy of Amal, someone stronger, braver, wittier, than me. Amal was supposed to protect my loyalties, my subjects, the people who did not ask to be written about, my lifelong friendships, and my family. But what I did not expect to happen at all, let alone in a few short weeks, was for Amal to forge her own loyalties with readers through comments, over Twitter, and email, with courageous strangers who shared stories and offered support. While they were virtual, brand-new relationships, the circumstances made them instantly deep and real.

Amal’s Gmail is white, with empty folders, and no accumulation of unanswered emails or unread articles. Her life is a clean slate. A new beginning. A second chance. My second chance. Amal became my amal, my hope.

So, until this regime falls, Amal will exist, not only out of true fear for those I left behind, but because what she has come to represent to you and to me.

Ibrahim and Amal, the leader and the hope, the past and the future, they guide me as I watch a new story unfold, a new history written, a new Syria reborn. One day, we will all be able to speak, write, imagine, sing, and create under our real names, with nothing to fear, nothing to doubt. We will meet there, as poet Sinan Antoon said, “under a new sun.”

![[Ibrahim Hanano and company. See text for description. Image from Amal Hanano.]](https://kms.jadaliyya.com/Images/357x383xo/hananohcover.jpg)