It has been called a #lifestyle on social media (#اسلوب_حياة). The van number 4 has become a social phenomenon, as well as an economic one. Here, we call it an intersection between contradicting places where strangers from different classes share the journey from the informal area of Hay el-Sellom in south Beirut to the cosmopolitan neighborhood of Hamra in the Lebanese capital, and back.

In most third world countries, informal public transit pervades the urban fabric. The need to move within the city has given rise to private “informal” services to compensate for the absence of an adequate public transportation system. In many cases, this sector is proving to be a worthy substitute for state services. Each country has its own version of informal transportation: small buses, three-wheelers, or motorcycles. They go by different names: rickshaws in India, tuk-tuks in Thailand, matatus in Kenya, and jeepneys in the Philippines. In Lebanon, privately operated buses and vans run within the Greater Beirut Area and across provinces, linking seemingly distant places for relatively cheap fees. High percentages of the population depend on such informal transport.

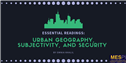

In this paper, we examine the specific case of van line number 4 (خط الرقم 4), as part and parcel of the monopolized privately operated common transport in Lebanon[1]. We further investigate the dynamics and specificities behind the number 4’s system, which moves 56,250 passengers per day (Figure 1). Through analyzing its socio-economic and organizational structure, we attempt to answer the following question: How did this system start and persist, considering the failure of all other attempts in the public transportation sector in Lebanon? Our fieldwork uncovered the different economic, social, geographic, and political layers underlying the system. The success and persistence of van number 4 can be attributed mainly to the monopoly, power, and reinforced organized structure that created it, and still holds it. We also find that, contrary to popular belief, van number 4 is neither chaotic, nor strictly used by lower classes. The appreciation of its passengers and drivers is also a clear indicator of its success.

Our research methodology consisted of data gathering and fieldwork conducted over a period of fifteen days in December 2014 and January 2015, during which we interviewed thirty passengers in the van during their trips, at different times of day and on different days of the week. We also visited the parking stations, or maw’af[[2]], and interviewed ten drivers as well as the bosses of the line, and two managers from the Lebanese Commuting Company (LCC), which is a private company that also operates common transport buses within Greater Beirut and its suburbs.

[Figure 1: Van number 4’s organization and turnover. Note that the total sum of expenditures per driver per day (maw’af or parking, rent, and fuel) is 100,000 LL (about $70), which makes a driver’s total gross income amount to 200,000 LL (about $135), which means a Net/Gross of 0.5. Source: Authors’ interviews, 2015.]

Overview of the System

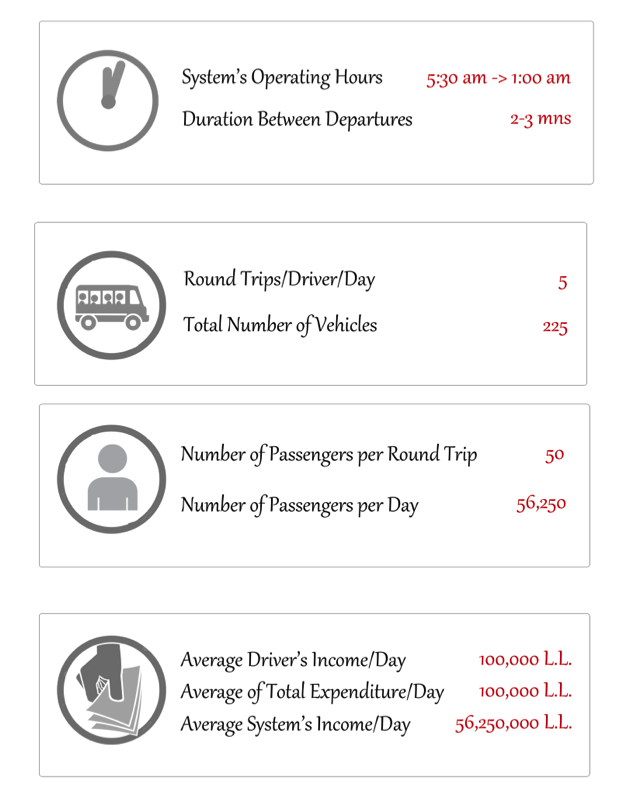

The van’s trajectory starts from Hay el-Sellom, near the campus of the Lebanese University, and reaches Mar Mikhael Church (Chiyah) through Al Sayed Hadi Nasrallah Highway. It continues then towards Tayyouneh, Ras el-Nabeh, reaches Downtown (Beirut Central District, BCD) passing by Bechara el-Khoury avenue, and stops near the American University of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC), in Hamra (see map in Figure 2).

Zigzagging along the green line, the van’s trajectory is one of its most important features on both social and urban levels. The van is an efficient mobility system that enables crossing long distances for a cheap fee. For 1,000 LL only ($0.7), residents of Dahiya—the dense southern suburb of Beirut—can reach Ras Beirut, and more specifically the corniche which is within walking distance from the van’s trajectory, the main open public space in the city. The bus also connects the Lebanese University in Hadath—an otherwise disconnected campus, to major destinations such as Hamra, Achrafieh,,and Downtown. Testimonies from the Lebanese University graduates confirm how the van made it easy for them to go eat pancakes late at night on Bliss Street in Hamra. By linking efficiently distant districts, and granting mobility to different socio-economic classes, van number 4 is able of tying marginalized neighborhoods to the city, thus enhancing social mixity in a highly polarized and segregated context.

.png)

[Figure 2: Van number 4’s route showing the three parking stations: the yellow dots indicate the stations

managed by Hezbollah, the green dot is run by Amal movement’s representatives. The dots’ sizes are relative to the number of vans affiliated to each station. The brown zone shows the area from which people can walk to reach the van. Source: Authors, 2015]

The line was inaugurated in 2000. It currently has three parking stations (see Figure 3), and is managed by three different men who operate very much as “bosses.” Two are associated with the syndicate of drivers in Haret Hreik affiliated to Hezbollah (indicated in yellow on the map), and the third (indicated in green on the map) to an Amal affiliated syndicate (اتحاد الولاء).[[3]] All three men belong to the Z’aiter tribe, and coordinate amongst each other the organization of the vans’ work. They supervise around seven “operators”[[4]] at the three stations, and one near Mar Mikhael church to collect the coupons from the drivers and ensure that they are abiding by the norms [[5]]. These bosses are welded both by their financial interests, and their sectarian (Shi’i) bond, or assabiyya. Although the tight tribal hierarchy was somehow weakened by the interference of political parties, it still forms a significant social system of regulations and norms.

The drivers themselves generally own vehicles. Today 225 vans circulate along the line, only fourteen of which are large buses. Around four hundred men make a living working as drivers. They have the option to rent or own the vehicle they run, so two drivers can work on the same van on different shifts. The average income of a driver who rents the vehicle is 100,000 L.L. per day ($70). As for a vehicle owner, it is 150,000 L.L ($100). Detailed explanations of the organization and economic structure of the system are elaborated in the last section. Before that, we present a brief historical overview and go over the social characteristics of van number 4.

[Figure 3: The parking station of the Lebanese University. Image by Petra Samaha]

.png)

[Figure 4: Inside view of the vans, showing their dire condition Image by Petra Samaha]

According to the founder of the Lebanese University’s parking station, the system began in 2000 with thirty-five vans, replacing the fleet of the LCC. Earlier, as of 1996, large LCC buses roamed the streets of Beirut, providing public transportation services as a replacement for the state’s transportation networks whose public buses decayed, and went out of service. The company also insured all of its fleet and passengers, and provided social security to its employees, paying regular taxes for the state, as well as required vehicle inspection fees.

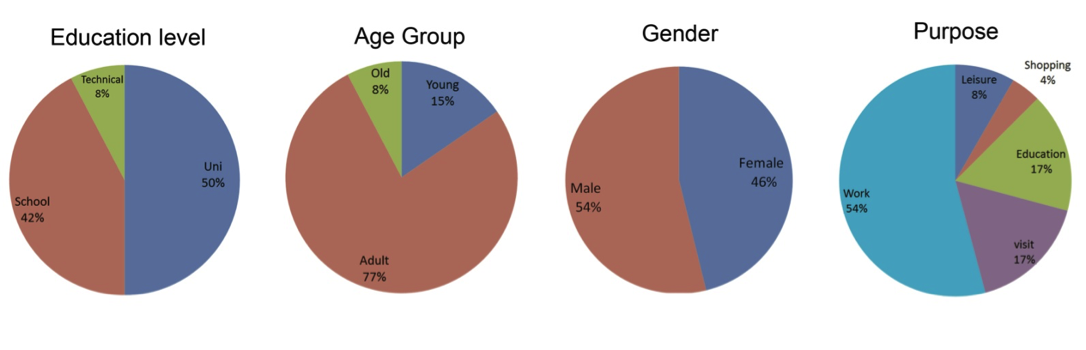

According to our interviewee, the entire LCC fleet grew from ten buses in 1996 to a peak of 225, before it started regressing in 2005, when the political and security situation in the country worsened. LCC buses not only filled the gap in the absence of public transport, but also introduced a new transportation system by conceiving their own route network, and assigning numbers to the routes (see Figure 5). After the overthrowing of LCC from the grid of public transportation in Beirut, the new operators who took over and controlled the lines separately, retained the same trajectories and their assigned numbers.

In the case of van line number 4, the replacement process was not an easy one. It was the result of years of conflict that involved violence, such as the sabotage of LCC buses and threats against their drivers. According to a manager in the LCC, arrest warrants were later issued, but no one was arrested. The Internal Security Forces personnel were either bribed to cover up or did not interfere at all to quell the violence. In 2004, only two LCC buses kept operating on the line, and remained until 2008.

[Figure 5: The LCC bus network as shown in a pocket map]

Like the case of line number 4 that was taken over by the Z’aiter family, political or territorial power groups seized most of the LCC lines.[[6]] Public authorities play a minimal role in organizing the sector. The state controls, and organizes the common transportation sector in four ways: issuing red license plates [[7]] and special drivers’ licenses, setting transportation fees (without enforcing them), as well as regulating the environmental specifications of the vehicles by prohibiting diesel engines. Moreover, the right to operate collective transportation does not require an official state license as it is actually enforced—mostly violently—by territorial, sectarian, political, and/or tribal hierarchies. This was one of the main causes behind the regression of LCC services to its current state: LCC only operates now line number 12, and a bus line that transports Beirut Arab University students from Beirut to their campus in Debbieh, a thirty-minute ride south of Beirut.

Users’ Satisfaction

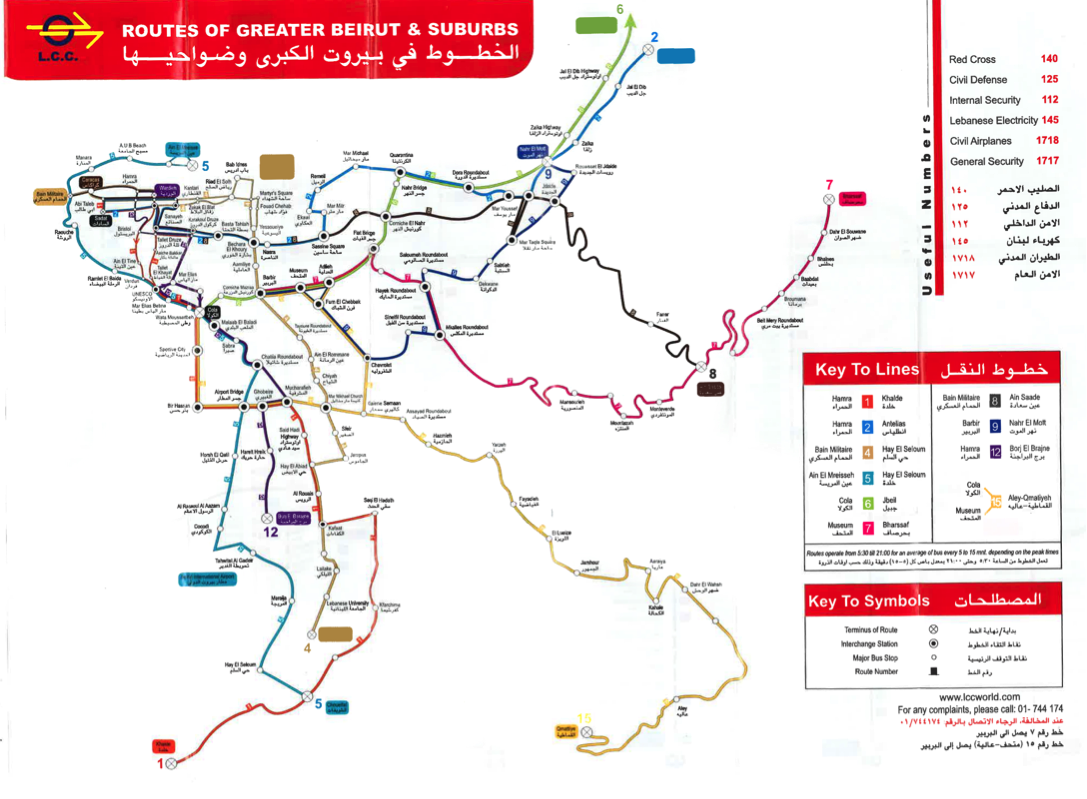

The trajectory of van number 4 is one of the main reasons behind its high variety of users, in terms of gender, age, and educational levels (see Figure 6). For instance, both students from private universities such as AUB and from the public Lebanese University use it, in addition to AUBMC staff, European tourists, and migrant workers. The catchment area around the van line varies as people walk from varying distances to reach it (see Figure 2): eighty-eight percent of interviewed passengers walk to, or from their destination, for an average of three minutes.

[Figure 6: Diversity of users and uses of Van Number 4. Source: Authors’ survey, 2015.]

Passengers use van number 4 for diverse purposes: work, leisure, family visits, education, and so on (see Figure 6). Even unaccompanied minors ride the van to go to school, or to visit relatives. Females, especially young girls, prefer it because they consider it safe. An eighteen year-old veiled young woman insisted on explaining how she finds it safer than the taxi-service, because it is rarely empty, and has a known route avoiding abandoned and unsecure alleyways—unlike the taxi-service that she perceives as including the possibility of “being kidnapped.” Another indication to the van’s perceived sense of safety is the fact that families frequently use it. During our fieldwork, we interviewed a family of four, living in Dahiya, who were going out to spend their afternoon at Zaituna Bay in downtown Beirut. The family considered the trip in van number 4 as part of their outing. The father stated that he finds the van very safe to take his family in, and enjoys not having to drive while having conversations with his family. Drivers themselves show a lot of pride, speaking about safety, accountability, and how they “protect” young females aboard from being harassed. Drivers and passengers often call van number 4 “andaf khat bi lebnen” i.e. the most decent bus line in Lebanon.

Looking at current transportation trends in Lebanon, the most used mode is the private car, as it reaches eighty percent, with eighteen percent for taxi-services, and 1.7 percent for vans (cf. Council of Development and Reconstruction figures). However, our fieldwork shows that of the sample we interviewed who have access to a car, forty percent prefer using van number 4, because it is cheaper, faster, and safer. They mentioned the hardships that come with driving private cars in Beirut, such as traffic, and the quasi-impossible quest of finding a (cheap) parking spot, especially in Hamra. These testimonies reveal the efficiency of van number 4 as an alternative mode of transportation, as well as the high level of users’ satisfaction and appreciation. This has allowed it to become a preferred choice of transportation, disputing the dominant use of private cars. Most importantly, this finding challenges the common perception that those who have no alternative transportation are the sole users of public transportation.

While each passenger has his or her own way of expressing their satisfaction vis-à-vis van number 4’s services, a main public source of evidence of the van’s success with people is the strong public support shown for it on social media. In addition to an Instagram account, there is also a very dynamic Facebook page, including regular testimonials shared by passengers and drivers. A father posted there the first selfie taken in the van with his two young daughters (see Figure 7).

.png)

[Figure 7: Screenshots of van number 4 fans’ Facebook page]

Drivers and Passengers: Common Practices

The relationship between drivers and passengers is based on practices that were incrementally developed, and negotiated to ensure a smooth trip. For instance, passengers give prior notice to the driver if they do not have change for the fee trip of 1,000 L.L. In such cases, and if the passenger is sitting among the back rows, s/he passes the money from seat to seat until it reaches the driver, and s/he will receive the change back the same way, in due time before reaching her/his destination, as not to stall the trip.

In addition, and typically of all collective transportation lines in Lebanon, there are no specific bus stops for number 4. However, a common code is to avoid asking to be dropped off on a green light. Also, to ensure a pleasant ride, passengers carefully choose their seats in the van, such as taking control over the window. Some passengers use earphones as a barrier against socialization, and for having control over the music they want to listen to, especially if they do not like the driver’s taste. Others, especially the elderly, prefer engaging in conversations, perhaps in order to kill time during the trip.

What distinguishes van number 4 is the short wait time: a passenger spends about two minutes waiting for a spot in the van at peak hours. Sometimes, several vans arrive together to pick up passengers, leading drivers to fight over clients. In other instances, they drive side-by-side, and initiate conversations if they happen to be related or good friends. A one-way ride ranges between forty-five and sixty-minutes, depending on the traffic, and the competency of the driver. Drivers also have the privilege of changing their route to avoid traffic—a practice which is much appreciated by passengers. They could also simply decide not to reach Hamra, because of blocked roads and traffic. Here, drivers strike deals between each other to exchange passengers, where one van would give his remaining passengers to another van that has more passengers heading to Hamra. Additional tricks that canny drivers also use, is intentionally slowing down their movement to increase their chances of picking up more passengers, especially if another driver has departed shortly before, and has most likely collected the potential passengers ahead—they refer to it as “nayyim,” which literally translates as “put to sleep,” and is understood as stalling. To facilitate their movement’s slow down, van drivers might choose to drive behind a taxi, which has frequent stops, faking they are as annoyed by this delay as their passengers. They may also decide, unconventionally, to respect the traffic lights, and stop at the red ones. Such negotiations form a set of codes and norms that both drivers and passengers progressively learn and practice, ensuring each other’s convenience.

[Figure 8: Image showing two van drivers greeting each other, assessing each other’s number

of passengers, and agreeing on driving strategies. Image by Petra Samaha.]

Power Structure

The efficiency and success of van number 4’s system can be attributed to two interdependent elements: power structure and economics. One of the main pillars of the line’s success is “organization” (tanzeem). During our fieldwork we were able to witness how the bosses and operators manage the fleet of 225 vans and drivers, and insure a smooth and efficient operation. An employee sitting in a shack next to the Hay El-Sellom’s station holds a stopwatch. In front of him, on the table, are some papers and a pen. “It’s your turn!” he shouts, and a van departs. He re-sets the clock, and starts the countdown once again, and so on. The two to three minutes departure time is regular, yet flexible enough to adapt to demand: at peak hours, the waiting time decreases as the vans fill up quickly, and depart. This daily routine is maintained at each of the three stations. Through this organizational process, the operators are able to limit quarrels between drivers, and maintain a constant, and frequent flow of vans, thus increasing the line’s reliability and punctuality.

Although the fleet grew incrementally since 2000, the same individuals who established it still manage and operate it. Through our fieldwork, we uncovered a power structure that holds the system together, and secures its sustainability. Influential figures belonging to the same family/tribe, and sect, manage the stations. All the drivers obey, and respect them: their word is rarely contested, as they are the final arbiters in daily quarrels, and random issues. Each one of these individuals is known as the mas’oul. While interviewing the mas’oul at the Lebanese University station, he received a phone call: “Yes, I solved the problem, it’s all been taken care of, it’s done… I will see you in a bit.” Such phone calls are part of daily practices to solve problems, and mitigate conflicts. The mas’oul sometimes act as a judge settling disputes between drivers, and listening to complaints of customers, particularly females, hence gaining customers’ trust, and reinforcing the number 4’s reputation as the “most decent van line in Lebanon.”

Our visit to Hay El-Sellom also demonstrated the control, power, and respect the bosses hold. When we first arrived, we were able to interview some drivers, until the boss arrived, and wanted to know who we were. He insisted we sit in his open concrete kiosk, and have coffee. Then, he investigated the purpose of our visit, and our intentions. He was annoyed by our ignorance of who he was, and got offended when we asked if he was a driver. As more drivers started to gather around, and make jokes with him, he shouted: “Come on, everybody back to your van, go take care of your business!” clapping his hands as a gesture indicating they need to proceed quickly. In a matter of seconds, all the drivers disappeared, except for his brother, and the timekeeper, who resumed their business, while we carried on with our interview. It was clear he was attempting to control our access to information: for instance, he tried concealing the actual daily income of the drivers, before eventually loosening up, and revealing the figures we mentioned above, in Figure 1. Irrespective, the boss’ power is never challenged, for his authority enforces rules, and equality among drivers, allowing a regulated and disciplined operational environment, that is what makes passengers feel safe. All the stakeholders recognize the importance of this organization in insuring a smooth working of the system: drivers understand the advantages of commitment, and discipline, while bosses need rules to monitor the number of drivers, and limit the oversupply that might cause quarrels, and loss of profit. Hence, the power structure of van number 4 is very well respected.

In some instances, the relationship between the drivers and operators goes beyond one of mutual business interests, and becomes dependent on respect, tribalism, and/or political and sectarian affiliations. For example, when some van owners started hiring illegal Syrian drivers, their Lebanese counterparts got annoyed, and considered them unfair competition. However, due to the social hierarchy, and common tribal origins between owners and Lebanese drivers, the latter did not protest or object. One driver told us: “I cannot say anything to the man allowing Syrians to work [the operator], he is of the same clan as mine [Z’aiter], and I am not going to start trouble with him. But of course, many drivers are not okay with this!”

Economics

In order for a driver to work on the van number 4 line, one must have a legal registered van, a red license plate, and the appropriate driver’s license. It is not common for informal bus lines to enforce these rules, however van number 4’s bosses insist on these conditions, perhaps to control who has access to work on the line. Then, the driver has to pay a one-time $100 fee, followed by a regular 10,000 L.L. ($7) daily subscription fee (except on Sundays) to the boss of the station he is assigned to. Based on our calculations, the total daily sum paid by all the drivers to the bosses adds up to 1,800,000 L.L. ($1,200)—assuming eighty percent of the total number of vehicles (180 out of 225 vans) is operating daily. This amount covers the salaries of the few employees that operate the stations, the land rent from the respective municipalities, and unknown fees paid to the syndicates. The basis for profit sharing between the bosses, and the different stakeholders (including bribery) remains unknown as the interviewed bosses refused to reveal the true distribution of the 10,000 L.L. daily fees. The income that the bosses earn goes most probably untaxed, since they are not an actual registered company, like the LCC is. The drivers working on the line are not registered employees; hence the bosses do not pay insurance fees, and are not responsible for the vehicles’ repair and registration.

Besides, the fee paid by the passengers has been constant at 1,000 L.L. since 2008, with one noted attempt to increase it in February 2012, that only lasted for a couple of weeks.[[8]] The fee of 1,000 L.L. covers the different driver’s expenses, and provides him with income. The driver’s expenses include the van, and license plate rental if he does not own the vehicle, the fuel, the daily station’s fee, regular repairs and oil changes, and an optional weekly charge of 3,000 L.L. ($2) to use the station’s bathroom. Usually both the van and the license plate are rented, or sold together. A van without a red plate cannot operate on the line. The plates are limited in number, and are quite expensive ($20,000 each). The plate comes with social security benefits, which can be passed on to the renter, and cover the driver and his family. If the van/plate is owned, then the net profit of the driver will increase.

Figure 9 shows the proportional distribution of daily expenditures, and gross profit with respect to the 1,000 L.L. fee. Here, the balance between supply and demand is fundamental for the efficiency of the economic model. The fee is affordable for passengers ensuring constant demand (56,250 passengers are moved daily), yet is enough for the drivers to make a living, (100,000 to 150,000 L.L. net income per day, i.e. $70-$100), thus ensuring sufficient supply for the 250 vans operating daily. High population densities that ensure the constant flow of passengers also maintain this balance between supply and demand. As the boss of the Hay El-Sellom confirms: “In the morning, people come in large groups, waiting in turn to get in a van.”

.png)

.png)

[Figure 9: Distribution of daily expenditures for a van’s owner vs. a van’s renter. Source: Authors survey, 2015]

Another component that contributes to the supply balance is the fact that not all vans operate at once. Despite the fact that drivers choose their working shifts themselves, these are directly related to demand and peak hours. The calibration of their schedules responds to the supply and demand curve to sustain sufficient revenue. The number of drivers working simultaneously varies across the day, to accommodate the demand, and prevent oversupply (which leads to the dissatisfaction of drivers), or undersupply (which leads to the dissatisfaction of passengers). The drivers’ schedules are not set by a fixed rule. This is not as easy to achieve as one might think, especially given the high number of vans. It was probably through several iterations that the current calibration was achieved.

A final note concerning the equilibrium of the van’s economic system relates to the van’s sophisticated institutional structure, which is based on several variables: vehicles size, frequency, number of drivers, drivers’ schedules, pricing, peak and off peak hours, and so on. The calibration of all these variables has made of van number 4 a successful and efficient line, reaching an optimal supply and demand curve, satisfying customers on the demand side, and keeping drivers’ profit high on the supply side, while feeding the power structure managing it financially and politically.

Conclusion

A first reading of van number 4 may show it as chaotic, and unorganized. However, decoding its operation reveals how it is, in fact, an incrementally constructed system that defies, and re-defines different socio-economic variables, while reinforcing socio-political hierarchies in order to persist. Van number 4 has proved to be a successful economic model, and an interesting social phenomenon in the field of urban transportation, providing a service that should be delivered by public agents. The van plays an important role in social mobility, and breaks conceived and perceived boundaries by creating a lived urban experience through a journey that blends social classes, and transcends geographic and political boundaries. Daily trips along the bus line from Dahiya to Hamra in both directions allow commuters to keep up with a city in constant flux. It contributes to the mobility of a substantive group of Beirut’s dwellers, and demonstrates the potentials of shared public transportation systems to become a viable and strong alternative, and contend the reliance on private transportation in the city.

While van number 4 reveals a noteworthy level of management, and organization, in a generally informal law-dodging sector, it does not diverge from the political, territorial, sectarian, and, in its case, tribal, control over the private/public transportation sector in Lebanon. Van number 4’s operators evade payment of taxes to the state, and the provision of social insurance, and other social benefits to workers of the line. The state does not interfere in the operation of these systems (such as designating the trajectory of the transportation routes, or selecting the private companies that operate them). As stated earlier, each line is subordinate to the local power holders of the region it operates within. In the absence of state-led public transportation, or state regulation for the privately managed transportation sector, access to this “market” remains a privilege for well-connected individuals, and influential power groups, enforcing their control through violence and/or shady deals, and bribes. Thus, in this highly unregulated sector, and within the inefficient enforcement of traffic laws by the state, the level of the provided service is strictly in the hands of the powers or stakeholders in charge.

In this paper, we argued that the decision of van number 4’s managers to provide a level of regulation, security, and convenience has provided them with the trust of passengers. Added to the political, sectarian and tribal support, we showed that the efficiency of the system is insured through the level of organization and daily drivers’ practices, as well as the vital and strategic importance of the trajectory itself, cheap fees, and high demand. All these have established a sustainable and successful franchise. Van number 4’s experience can offer many lessons to the state, whether it decides to regulate the private transportation sector, or to introduce its own public transportation services. There have been many successful case studies in which authorities regularized informal common transport, like in Bogota (Colombia).[[9]] How can this “informality” be integrated into Beirut’s transportation strategies and schemes, and how can the provision of an efficient and well-organized public transportation system proves to be a worthy replacement for private car usage?

[We would like to express our deepest gratitude to all of those who have helped us complete this research: our professors Mona Harb, Omar Abdul-Aziz Hallaj, and Charbel Nahas for their guidance, Rami Semaan for his generosity in providing the needed data, and Jadaliyya Cities Page editors for their rich comments. We would also like to thank the drivers and operators of van number 4, as well as LCC managers for their time and hospitality.]

[1] Khat (خط) indicates the whole van system, including the fleet and its operators, operating along a specific geographic route. Na’le: (نقلة) is the common word used for the roundtrip.

[2] Maw’af ( (الموقفis the parking station where a large numbers of vans gather, and wait in turn to fill in passengers before departing. It could be situated on a large empty lot, or on a roundabout.

[3] However, syndicates remain as unregulated institutions that are subordinate to political influence. They are divided according to political parties and are used occasionally to convey the demands of the drivers to the State.

[4] The mas’oul (المسؤول) is the person in charge of the parking station. He collects the daily fees from the drivers, helps in organizing the departure times, and ensures the smooth running of the process.

[5] The coupon or bon (بون) is a piece of paper given by the operators to the drivers at the departure of each trip. At Mar Mikhael church, an employee collects these coupons from the drivers. Without it, the driver cannot continue his route, and will be eventually penalized.

[6] Every now and then, drivers on many bus lines organize strikes to denounce “strangers” driving operating in “their territory.” See this article for more details.

[7] In 1996, the ministry of Public Works released a limited number of red plates into the market. The state has not issued any new red plates since, causing the emergence of a black market where red plates are traded. An official state office issues a market value approximation for these plates regularly; however these prices are not binding in any way. In addition, some drivers use the same (forged) red plate number on two or more identical vehicles, and operate on different transportation routes in different areas.

[8] The fee was 500 LL in 2000, when the fleet started operating. It gradually increased to reach 1,000 LL.

[9] In Bogota, the public transport system comprises today efficient red buses called “Transmilenio.” Before, it consisted of thousands of independently operated and uncoordinated mini-buses. A key lesson from this experience is the way the city’s government involved existing operators, and transport companies in the new system.