The Egyptian Armed Forces (EAF) is widely reputed to play an influential, even massive, role in the national economy. The EAF runs a parallel economy that produces a wide array of consumer products ranging from food products, dairies and wheat to cement, fertilizers, and fuel distribution. The military is also heavily present in infrastructure and public utility projects like roads, ports, tunnels, and bridges.

But contrary to popular thinking, the army’s share in Egypt’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is relatively small. Though limited, hard data shows that it is present in many sectors but does not occupy a commanding position in any, and indeed has no presence in a range of crucial economic sectors. There is little empirical evidence that the private sector has been crowded out by the military at all, with the possible exception of government contracts for new mega-projects in the post-June 2013 period.

The Egyptian military’s economic model is based on rent extraction. Through its broad legal and effective control of public assets, namely public lands that constitute around 94 per cent of Egypt’s total surface area, the military translates its regulatory mandate into an economic return. The military also wields considerable, if less formal influence through the large number of former officers who hold high level posts in the civil service, particularly in public land management. Public land is crucial for economic growth and for the development of essential sectors, including urban development, manufacturing, tourism, and agriculture—which, together, constitute the bulk of Egypt’s economy. More than any other factor, the chokehold on land use is costly for the economy. The complexity and opacity of the regulatory environment affecting access to it moreover adds to the inefficiency of the private sector. This results in significant opportunity costs for potential growth and urban expansion—in an overcrowded country that needs to expand settlement into the vast tracts of desert land to the east and west of the densely populated Nile Valley.

A Small Military Civilian Economy

Much has been made of the Egyptian military’s parallel civilian economy, which extends into agriculture, manufacturing, and services. But credible estimates reveal its share of total production in most of these sectors to be minute compared to that of the private sector, be it nationally- or foreign-owned firms. The military economy may seek market share, but it is far from being a dominant actor.

Historically, the original driver of the military’s foray into the civilian economy was the need to supply a large standing army with considerable consumption and investment needs. Also key was the need to compensate for its dwindling share in public expenditure since penning the 1979 peace treaty with Israel, which pushed the military to look for alternative sources of revenue. Because of the fiscal crises in the mid-1980s, the state attempted to offset the financial burden of financing the military by enabling it to reap certain economic benefits. The military thus began to expand into previously untapped markets, establishing partnerships with both Arab and foreign investment firms in the process.

This trend becomes evident when reviewing the economic enterprises of the military run- and -owned National Service Projects Organization (NSPO).[1] The NSPO, which was established by Presidential Decree no. 32, falls under the Ministry of Defense’s purview. The NSPO was established to provide the institutional and legal framework for partnerships between the military and foreign and Arab capital, and to find and secure independent funding sources. According to the NSPO’s official website, its mission is to achieve financial independence in the armed forces so as to minimize or alleviate its fiscal burden to the state while also providing surplus goods to local markets that exceed the military’s needs. The NSPO also aims to support the state’s economic development project through its modern industrial base. The NSPO currently owns and runs twenty-one companies that operate in a wide array of economic sectors including construction, agriculture, food production, and cement, in addition to directly managing hotels, security services, and one petrol station.

In May 2015, the NSPO issued, for the first time ever, an official statement disclosing the volume of production activities in firms it owns and runs. The statement was issued with the aim of demonstrating the Agency’s contribution to the state’s “comprehensive development”plan. The statement’s release, of course, comes in a context where the military is the de facto, albeit indirect, ruler of the country. The legitimacy of both the Sisi-led regime and thus the NSPO hinges on the military’s ability to promote economic development, or at least to be perceived as such publicly.

The NSPO’s production and distribution statistics are the only mechanism available for determining the rough market shares of its subsidiary companies in key economic sectors. In agriculture, for instance, the NSPO has reclaimed 100,000 feddans (around 50,000 hectares) in Sharq Al-Ouaynat in the western desert, where most military-owned farms are located. In 2013, these plots yielded around 78,000 tons of wheat, 156 tons of olive oil, 25,000 tons of dairy products, 2,000 tons of red meat, 60,000 tons of fodder, and about thirty million eggs. This produce was primarily used to supply a number of NSPO-owned firms that compete in the private sector, including the military-owned mineral water brand “Safi,” which produces around thirty-seven million bottles a year. In addition to perishable goods, the NSPO owns both the Al-Arish Cement and the Al-Nasr Companies, which annually produces between 2.5 to three million tons, of cement and about 150,000 tons of cement fertilizers, respectively.

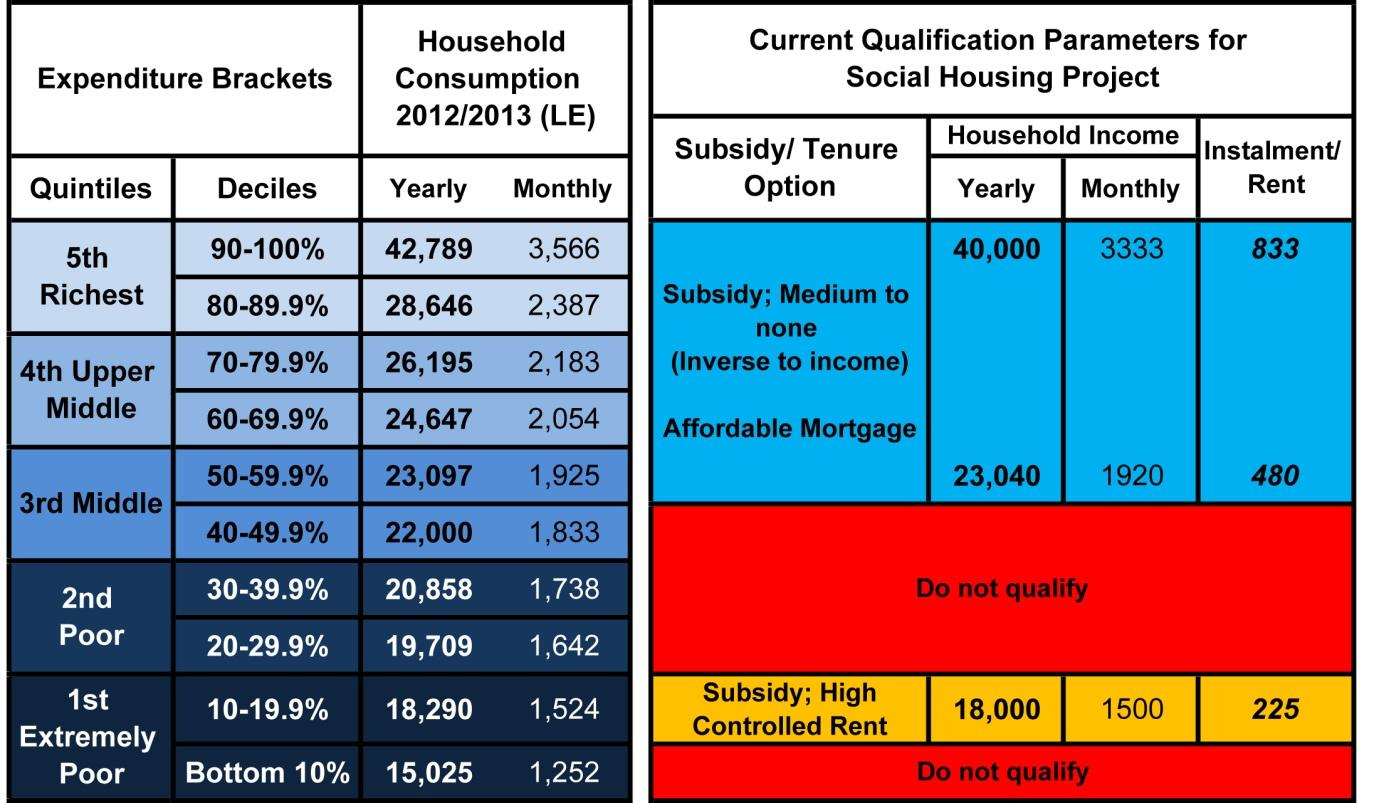

The table below lists total production figures, according to the Central Authority for Popular Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS) in 2012/2013.

Table 1: The military’s economic share in some sectors[2]

Two trends are discernable from the available data. First, the Egyptian military does appear to own a parallel civilian economy, yet this may indeed be justified considering the extent of materials required to supply an army of half a million service members. Second, the share of military-owned companies in none of these sectors is particularly significant—forming anywhere from a low of 0.18 to a high of 3.9 percent.

In agriculture, for instance, the vast majority of farmland mostly located in the Nile Valley and Delta is privately-owned. This has been the case since the Nasser era, despite the fact that most desert land in Egypt is owned by the state. The same is true of food production, even though the military’s limited role in that sector has traditionally boosted its popular support via subsidized handouts to the poor on national or religious holidays. And because there are low barriers to entry in the market for consumption goods, it remains difficult for any enterprise or actor—including the military—to dominate. In the case of mineral water, Nestlé holds twenty-six percent market share with Safi coming in a distant third with 3 percent.

Moreover, figures from the Central Bank of Egypt show that military-owned companies and the NSPO account for a negligible share of bank loans. Central Bank annual reports from 2002 to 2012 reveal that the state has become the largest borrower from the banking sector, but these loans are not related to military activities. Rather, the government competes with the private sector in securing loans to finance its ever-widening budget deficit. In an economy that chiefly depends on a banking-based system, the military’s tiny share of bank loans suggests that it has a limited economic role. Even if military-owned companies could do without resorting to the banking sector through some form of self-financing or earning-retention program, this itself would indicate that its firms do not require the extensive capital that only large banks can provide in the form of loans.

The military’s expansion into civilian economic activities appears to be a reaction to the state’s years-long policy of cutting back on defense and military matters. World Bank figures show that the military’s share of national expenditure has been progressively declining since the early 1990s, both as a percentage of GDP (from seven percent in 1990 to two percent in 2012) and in terms of total public spending. These figures include central government allocations, foreign military aid, and the pensions and wages of military personnel and civilian employees who do not hold military rank. The military, it appears, has simply responded to the downswing in state financing by ramping up its military economic activity as of the 1980s.

Figure 1: Military expenditure as a percentage of total public expenditure and GDP (1990-2012)

.png)

Source: World Bank development indicators

The military’s limited economic role

The military has been virtually absent or retained a tiny share in a number of key economic sectors that grew considerably since the 1990s. This includes a wide array of manufacturing industries like cement fertilizers, glass, ceramics, aluminum, and iron and steel, as well as key service sectors such as telecom and hospitality and tourism. In the case of cement, ninety-seven percent of total annual production is attributed to privately owned enterprises—mostly multinationals—along with publicly owned firms in which the military plays no role. Similarly, the bulk of fertilizers production has remained in the hands of the private sector since publicly owned companies were sold off in 2008 and 2009.

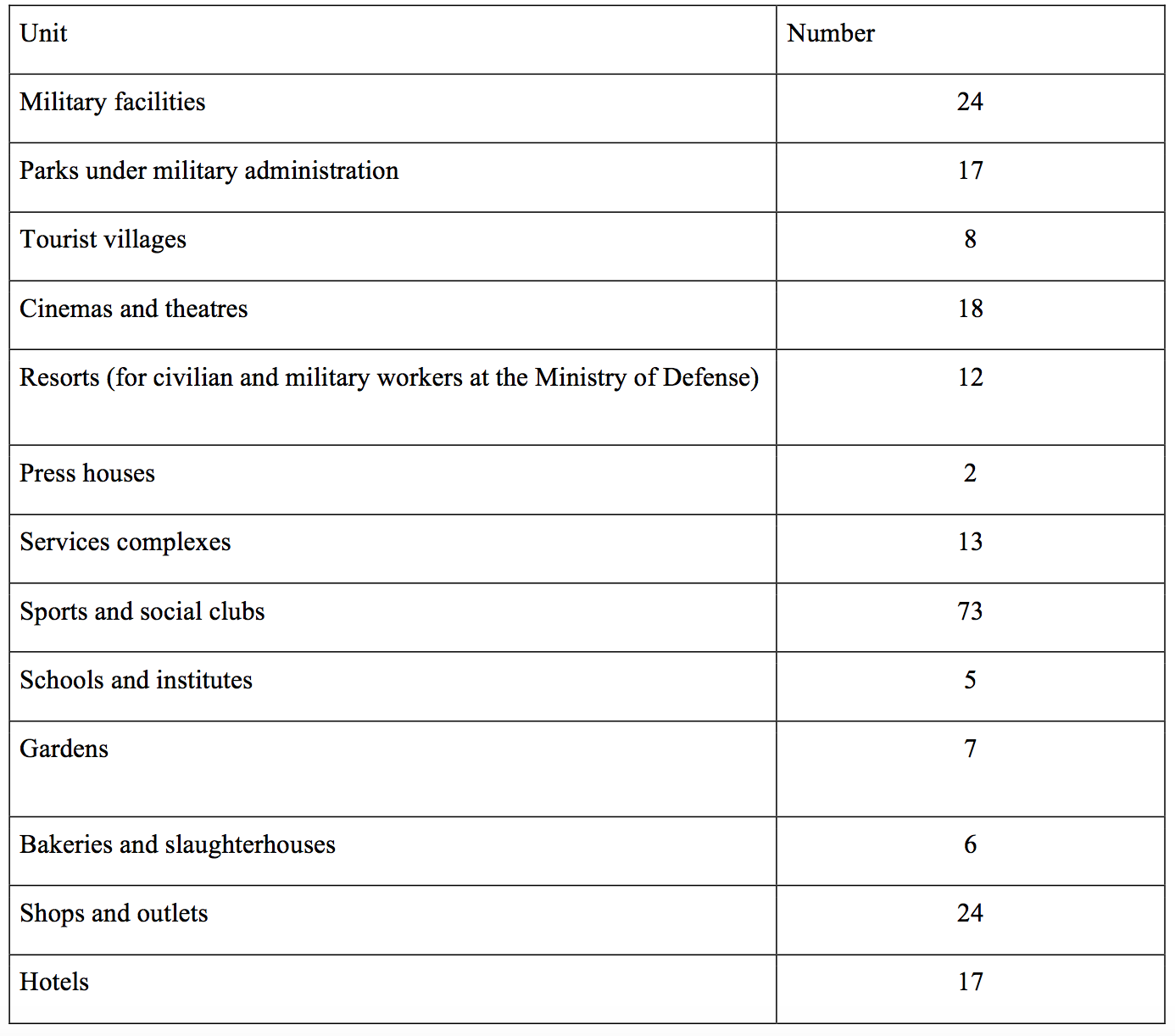

The same is true of significant service sectors such as tourism and construction. The minister of defense issued a decree, which was published in Al-Waqe’ Al-Misriya in June 2015, listing all the real estate units owned by the military in those sectors. The decree declared all of these buildings and the land on which they were built exempt from taxation. It includes facilities used for different social and economic purposes such as hotels, sporting clubs, parks, and schools. The decree makes no mention of other plots of land that are vacant.

Table 2: Military-owned facilities by use (based on author’s calculations)

Source: Minister of Defense decree issued in Al-Waqe’Al-Misriya issue number 127, June 3, 2015

These figures show just how limited the military’s economic share in the hospitality and tourism sector is. Most of the military-owned facilities only serve civilian or military workers employed in the ministry (and their families). And many of these facilities are moreover to be found in remote, non-touristic areas across Egypt. In the tourism-rich North Coast region, the military owns only four of the 128 tourist villages and hotels. The remainder falls under the ownership of the private sector—which expanded its investment in tourism considerably over the last decade—or that of cooperatives established by employees in ministries, public universities, professional syndicates, or the New Urban Communities Agency. That military-owned hotels are also virtually non-existent in touristic areas in South Sinai and the Red Sea coastal area also reflects the military’s limited economic role in that sector.

There is also little proof that the military plays a hegemonic in the construction sector, which includes infrastructure and public utilities such as bridges, roads and tunnels. Indeed, according to the Central Bank of Egypt publicly owned firms held 11.51 percent market share, with the private sector holding 88.84 percent.[3]

Since the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi in July 2013, the military has undertaken mammoth public infrastructure and utilities projects in the construction sector. According to both independent media and government-run newspapers, the total value of these projects allocated to the military between 2013 and the first half of 2014—under the interim Prime Minister Hazem Beblawi—was 5.5 billion Egyptian pounds. This investment surge occurred amid political turmoil and declining local and international assistance, which prompted the military to inject funds into economic recovery projects as a shortcut to political stabilization. But while the aggregate monetary value of these projects was significant, it constituted only about ten percent of total public investment in the 2014-2015 fiscal year. Even with these robust projects, the EGP 5.5 billion figure represents a mere 7.71 percent of all of construction activity in 2012-2013, or 8.71 percent of the private sector works done during the same period.

Nonetheless, there is anecdotal evidence that the military’s increasing involvement in megaprojects in the post July 2013 period is indeed coming at the expense of private construction companies. Major examples are the second Suez Canal, which was completed in August 2015, and the proposed one million-unit housing and New Administrative Capital projects. But while the military is crowding out the private sector in the specific case of government contracts, this is not generally true of the construction sector as a whole, where the private sector remains the dominant force. The recent presidential decree no. 466 issued in December 2015 allowed the army through its Armed Forces Land Projects Organization (AFLPO) to establish commercial enterprises, which it either owns fully or jointly with private national or foreign capital. This may provide the legal framework for future business deals in mega housing and infrastructure projects where the AFLPO-owned companies would enter ventures with their land reserve and engage in revenue-generating activities.

Securing Market Share, Not Dominance

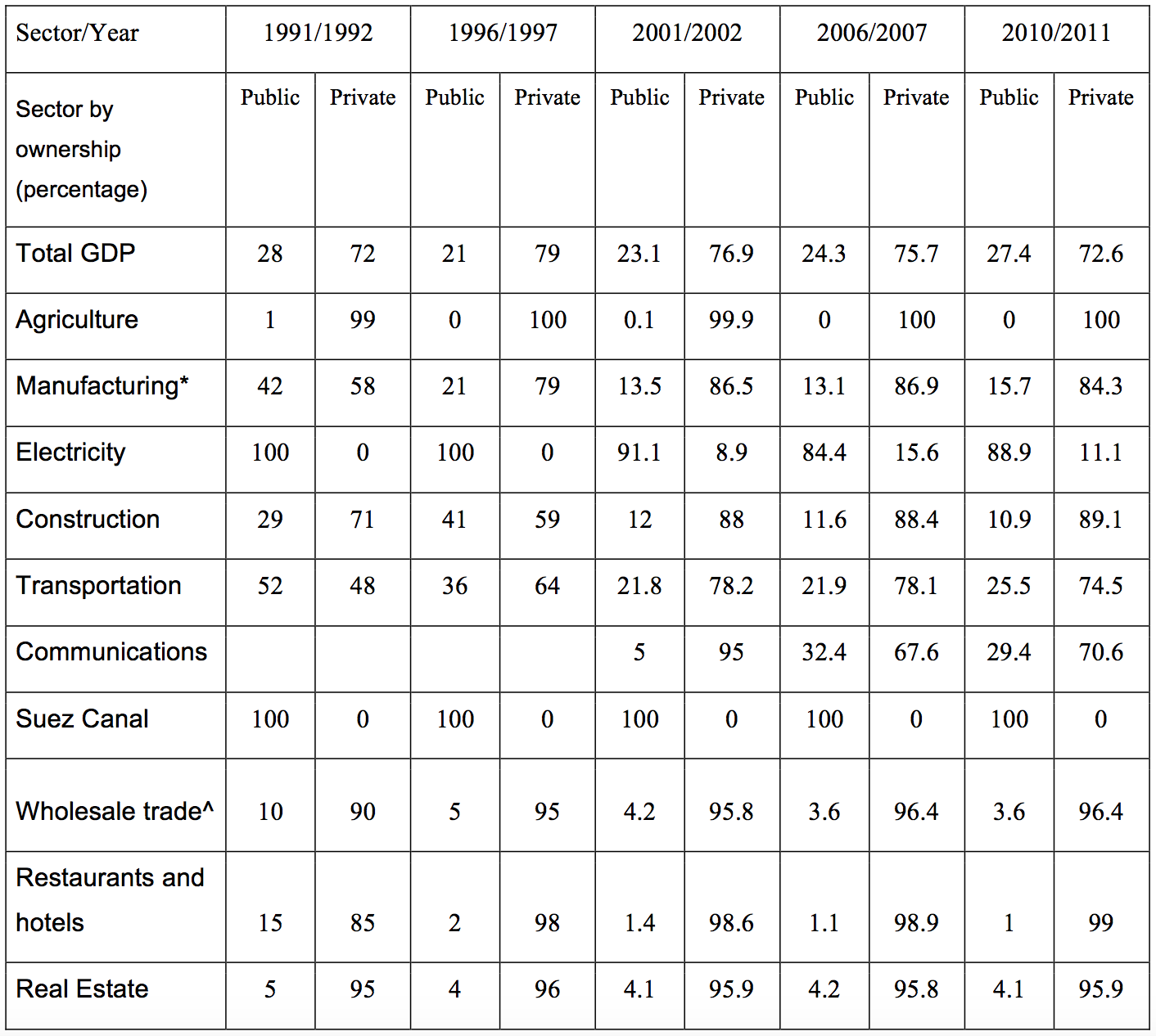

Far from crowding out the private sector, the military’s growing economic role since the 1980s has gone hand-in-hand with the private sector’s expanding share of the national economy. Large, medium, small, and even micro enterprises grew continuously since the 1970s following President Anwar al-Sadat’s open door (infitah) policy. By the early 1990s, private sector firms accounted for over seventy percent of the non-hydrocarbon economy in Egypt.

Table 3: Public versus private share of the non-hydrocarbon GDP. Figures exclude oil and natural gas, along with the government service sector

Source: Central Bank of Egypt, output structure at factor cost (1991-2012)

* Data for the 1990s referred to industry including manufacturing as well as extractive industries like oil and gas and minerals. Manufacturing is now reported separately. + Transportation and communications data for the 1990s were initially combined figures before being separated in the 2000s. 1990s trade data make no distinction between wholesale or retail trade.

The private sector has retained its dominant share of the total non-hydrocarbon GDP since the early 1990s. It has particularly increased its share compared to the public sector in trade, manufacturing, hospitality, transportation, and communication where growth rates have been most pronounced. The fact that this private sector expansion occurred as the military also increasingly forayed into civilian economic activities, suggests coexistence is possible and that the notion of “crowding out” warrants greater scrutiny.

It is not clear however whether the same division of labor will continue in future given the military’s evident interest in expanding economically since becoming the de facto ruler of the country since July 2013. So far, the military has generally kept away from economic activities that have been traditionally left to the private sector, with its expansion coming in infrastructure-related megaprojects. This may suggest a quantitative rather than qualitative shift in the military’s economic focus. However, the dearth of accurate information about the actual extent of the increase in the military’s economic activity in the contemporary era—as compared to the Mubarak era—makes arriving at a definitive assessment difficult.

Rent-seeking Rather than Crowding-out

While the military is not a dominant economic actor, it still enjoys unparalleled influence in one key respect: uncontested and broad regulatory control over the planning, allocation, and management of public lands. Therein lies the most distinctive feature of the Egyptian military’s problematic engagement on the economy. The military’s control over land considerably affects both the private sector and the broader economy’s ability to grow. The military, moreover, uses its legal and de facto regulatory sway to generate rent, particularly in uninhabited desert public land.

Indeed, the vast desert lands to both the west and east of the Nile Valley hold potential opportunities for future urban expansion or for investment in agriculture, tourism, energy generation, and manufacturing. State policy determines access to land and its price, as well as subsequent access to finance for private enterprises, given the fact that banks have high collateral requirements that usually take the form of land or buildings in order to extend credit to private investors. Moreover, houses are a crucial form of investment for the Egyptian middle and upper-middle classes who prefer to put their savings into real-estate units in the light of chronically high inflation rates.

Legal Rent

The military’s legal control over the use of state-owned land—including the allotment of desert land to private investors—is mediated through four specialized public agencies: urban development, land reclamation, industrial development, and tourism development. Separate laws apply to lands in the Nile Valley and the Delta, where the vast majority of Egyptians live. The laws governing public land are quite centralized, and no plot can be allocated without the initial approval of the Ministry of Defense, according to law no. 143/1981, which governs the use of state-owned desert land.[4] The Minister of Defense determines which desert land is to be used for military or strategic ends, rendering these lands unavailable for other public agencies or for private use. In the same vein, only the Minister has the legal right to alter lands earmarked for strategic or military purposes. He is thus the ultimate authority controlling the use of desert land.

The military has been influential, together with other state bodies, in setting the strategies and rules governing public lands since the 1970s, when plans for economic expansion into the desert were first launched. In addition to the military’s broad mandate over land earmarked for defense and national security purposes, it also enjoys some considerable influence over the subsequent use of desert land. This is achieved through two means. The first of which is formal, and relates to the Ministry’s continuous oversight in regulating land use. In many instances, investors must secure military approval for technical issues such as building heights or land mines clearance certificates.

The military is also entitled to compensation from the state treasury in cases wherein land used for military ends gets allocated for economic purposes, with their prior approval of course. The military’s approval is also required in allocation of lands in coastal areas—defined legally as borders—which typically attract high-value tourism investment, such as on the North Coast and the Red Sea.

According to presidential decree no. 531 issued in 1981, the military also has the right to auction off land originally used for military purposes, and to collect any proceeds for the construction of alternative military sites or facilities. This arrangement provided a formal channel for the military to convert its regulatory mandate over public lands to economic returns. In 1982, a presidential decree (no. 223) established the Armed Forces Land Projects Organization (AFLPO), vesting it with the power to manage the sale of military-owned lands, as well as the returns from building alternative military facilities. The Agency was given the mandate to receive the money and to deposit it into a special account at the National Investment Bank. A further presidential decree (no 233) in 1990 allowed the agency to deposit the returns from land sales into commercial public banks instead of the National Investment Bank.

Recently, the law was further amended through presidential decree no. 446/2015 allowing the AFLPO to establish economic enterprises that it may fully own and run or in partnership with national or foreign private sector companies. This is a new development that may pave the way for the direct involvement of the AFLPO in construction and service projects in the near future either solely or with private partners. The new amendment provides the legal framework for military business engagement in areas where the army already owns plots of land like the Suez Canal Zone and the new Administrative Capital.

Moreover, the military regulates investment in Sinai through the Sinai Development Authority. Under law no. 14 on comprehensive development of the Sinai, issued in January 2012, the president of the republic appoints the head of that body based on an initial nomination by the minister of defense. Crucially, the law grants the Sinai Development Authority all regulatory capacities pertaining to land allocation in the peninsula for various investment purposes.

De Facto Control

The military commands another mechanism of exerting influence over land allocation, which is less formal and is a result of the large number of individuals with military backgrounds who assume senior posts in civil service, particularly in public land management. This applies to almost all of the specialized public agencies such as the New Urban Communities Agency, which falls under the Minister of Housing but is heavily staffed by military retirees, as well as the Agricultural Development Agency, the Tourism Development Agency, and the Industrial Development Agency. Similarly, there are many retired generals staffed in the governorate and municipal levels. These local authorities manage land within the boundaries of governorates.

But this rentier approach to desert land is by no means confined to the military and is prevalent throughout the state altogether, including civilian bodies such as the New Urban Communities Agency and the Ministry of Housing, which are (mostly) financially independent. This rentier approach has also sidelined and even prevented a more logical developmental plan from emerging, specifically one that would consider the broader needs of the economy instead of just focusing on potential returns to the state coffers.[5]

The military’s presence in regulatory bodies also adds an extra layer of bureaucracy in the already-inefficient land management sector. It adds to the number, complexity, and time required for obtaining necessary licenses and permits. Some of these papers are obtained directly from the military and others from civilian bodies that also adhere to the same rentier logic, which the military first institutionalized.

The military’s mandate over public land, combined with ambiguity over the legal and administrative rules governing land use, raises the private sector’s cost of accessing land. This applies to both the direct costs to investors and the indirect costs associated with complex legal procedures. The designation of land for national security and defense purposes, which is subject to vague guidelines and discretionary power, weakens landholding and property rights. The most restrictive law was Presidential Decree no. 7, issued by then-President Hosni Mubarak in 2001, ruling that “strategic areas” that fall under direct military jurisdiction cannot be appropriated or allocated by any private or public actor. The text of the decree repeatedly refers to a map showing the designated areas, but this has never been made public on grounds of “national security.”[6] Consequently, government agencies and private investors alike are unaware of the precise location of affected areas, and potentially face complex procedures should they plan to invest in an area that proves to be adjacent to a “strategic plot of land.” The military can (and perhaps does) use this informational asymmetry to generate rent by retroactively designating lands as “strategic” and altering its permitted use.

This unfair and opaque system results in opportunity costs for potential growth and urban expansion—in a overcrowded country that needs to expand settlement into the vast tracts of desert land to the east and to the west of the densely populated Nile Valley. Government policy therefore not only impedes affordable growth, but also hinders employment and investment opportunities. Public land is a significant resource for governorates overlooking desert areas, but the rentier system denies them the ability to realize the full potential of these areas. This is especially detrimental to small- and medium-sized enterprises, which face greater obstacles in this respect due to having more limited resources than their larger competitors.[7] Bureaucracy and nepotism is also inflating housing prices and blocking the expansion of developing much-needed settlements. This artificial scarcity has been a factor behind the expansion of informal settlements where people have opted for illegally building homes on agricultural or public land without securing permits or acquiring tenure, which in turn impedes their access to bank loans or other forms of credit.

Re-modeling Public Land Management: Moving beyond Rentierism

Since the 1980s, Egypt has witnessed the simultaneous expansion of the military economy and the private sector without crowding each other out. This has most probably been achieved without much foresight, through a sectorial division of labor between the two. The real problem lies in the broad legal as well as de facto mandate that the military enjoys over public assets, namely desert land, under the pretext of defense and national security. This sweeping regulatory capacity has often raised the cost of investment for the private sector, either through adding more complex and lengthy procedures or through extracting rent, officially or unofficially, for accessing public land.

Publicly-owned desert land is of extreme importance for Egypt’s future development, since it constitutes around ninety-four percent of the country’s overall surface area. Future investment in housing, land reclamation, tourism, industry and energy generation are all dependent on accessing cheap and theoretically abundant land to the west and to the east of the Delta and the Nile valley.

The current regulatory and legal framework and its rentier repercussions are negatively impacting the cost of investment, the social cost of housing for middle and poorer classes, and the overall question of the access to assets in Egypt. There is little room for any serious reform of Egypt’s current development model without tackling state management of public land, including the formal as well as informal roles that the military plays.

[1] This article does not tackle defense industry, which has never involved the private sector in Egypt. Nor does it address the U.S. military assistance averaging around $1.7 billion annually since 1979 and used primarily for training, modernizing, and arming the EAF.

[2] Sources: NSPO production figures obtained from official NSPO statement issued in May 2015, published in Al-Youm Al-Sabee. Total production figures taken from CAPMAS. Olive oil figures taken from the International Council for Olive Oil. Information on mineral water taken from the Euromonitor International. Information on petrol retailers is taken from Al-Ahram. The third column is based on the author’s calculations.

[3] Central Bank of Egypt, Output Structure in Egypt –by sector (2012/2013)

[4]Approval needs to be secured from the ministries of petroleum and antiquities together with defense, but the former two do not enjoy the political weight and influence of the latter.

[5] Yahia Shawkat ed. (2012) “Social Justice and Urbanity: A Map of Egypt” (In Arabic), Cairo, WezaratIsan Al-Zil.

[6]“Appeal Against the Decision of the Minister of Defense Concerning the Consideration of Al-Qorsaya Island as A strageticMiitary Zone”(In Arabic), by the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, The Egyptian Center for Social and Economic Rights, Al-Nadeem Center and Al-Hilali Institution, 2012, p. 15

[7] Rabee Wahba (ed), “The Land and Those Over it: Rights and Destiny of the Peoples of the Middle East and North Africa”(In Arabic), 2013, Cairo: Land Forum: the International Coalition for Habitat