On the morning of August 3, 2011, Egypt stood still as millions watched the televised trial of their former president Hosni Mubarak begin. The other defendants in Case 1227, Qasr al-Nil, were Mubarak’s two sons Gamal and Alaa, his tycoon business associate Hussein Salem, former Interior Minister Habib al-Adly, and six of his aides, variously charged with the deliberate killing of protestors, and profiteering on a massive scale. Traffic reduced to a trickle on Cairo’s streets, as shop-keepers, cafe owners and their customers gathered around television sets, whilst activists and martyrs’ relatives met at the screen set up outside the High Court of Justice. Others headed for the screen outside the courtroom itself, ironically housed in what was formerly named the ‘Mubarak Police Academy’. For most, reactions were a mixture of incredulous joy and anxious hope that justice truly be done. Others lamented the demise of Hosni Mubarak, who for them was an Egyptian statesman after all. Still others, particularly those who had participated in the recent July 8 protests, voiced their pride and sense of vindication at having brought the Mubarak regime to account. They remembered those who lost their lives in the struggle against it and could not see this day.

An historic event by any measure, Mubarak’s trial invites reflection in and of itself, but also as a barometer of the fortunes of the January Revolution as a whole. A common challenge confronts both the achievement of accountability in the trial, and the fulfilment of the Revolution’s demands, namely the role of the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF). Since it took power in February, there has been much talk of SCAF ‘collusion’ with the old regime. In reality, the generals have been stalling Mubarak’s trial to protect their own interests, as well as those of certain Gulf monarchies, also taking into account their relationship with the United States. As Mubarak’s defence now attempts to expose these interests, the SCAF is likely to respond forcefully, combining repression, diversion and media control. The democracy movement will have to be wary of the divisive impact of these tactics: fortunately, the trial’s sound progress is a unifying concern. If the trial does see a new faultline prised open, between the SCAF and Mubarak, this may well alter the balance of power between the SCAF and the revolutionaries.

In the long run, if the process is deemed fair and the regime’s crimes exposed, the trial will become an emblem for the Arab uprisings, and a cautionary tale for remaining despots, their allies abroad, and aspiring leaders. Whatever this single case’s outcome, it has certainly revitalised the quest for accountability which was so central to the popular revolution of January 2011.

Historic Moments: Highs and Lows

The first hearing itself had all the components of a drama – tension, character, conflict, and spectacle. It was scheduled for 9 a.m., and many had camped outside the Academy building since the early hours, awaiting reassurances that Mubarak had indeed arrived. Suspense began to build after the first sight of his helicopter, crushing powerful predictions that he would ultimately fail to attend. Unforgettable moments followed with the first glimpses of Alaa Mubarak and Habib Al-Adly hovering outside the dock, as well as the image of Mubarak in the line-up shielded by his sons. Then came the roll call of the three, and their cool d enial of all charges in steady succession. The prosecution’s recital of these charges created probably the most moving and triumphant moments for this Revolution since Omar Suleiman’s February 11 announcement of Mubarak’s resignation. Listening to them, seasoned activists and others who had lost family members to the Mubarak regime’s violence broke down outside the courtroom.

Last to arrive and first to leave, Mubarak was carried into court on a stretcher. This was a surprising twist, since many had predicted a wheelchair at most, after successive medical reports from the Ministry of Health had confirmed Mubarak’s fitness to stand trial. Many feel that this was an attempt to gain the sympathy of observers, which dismally failed. Poet Mourid Barghouti expressed revulsion at the Mubaraks’ sour and unrepentant faces throughout the proceedings. Prominent psychiatrist Ahmad Okasha noted that the former president’s stretcher, unattached to any medical equipment, seemed unnecessary. Even jokes on the subject quickly began to make the rounds across mobile networks. One of these noted that if the defense prolonged the case, the lawyer would probably die before Mubarak. Another parodied a popular advert campaign for non-alcoholic beer, which helps the consumer toughen up apparently, to warn against sympathising with Mubarak. When Ahmad Rif‘at, President of the Criminal Court and presiding judge, declared that the former president would finally be moved to a Cairo hospital, far from his hideaway in Sharm al-Sheikh, congratulations immediately began circulating online on the ‘liberation’ of Sharm and Sinai.

Alongside these signs of a well-received and credible first hearing, there were also disappointing scenes which require explanation. First came the image of the courtroom looking a third empty, when hundreds who had travelled to Cairo from across Egypt had struggled in vain to get in. Thousands more had not even applied for access, having considered the martyrs’ families far more entitled to attend. According to Mohammad Manee‘, Assistant to the Minister of Justice for Courts Affairs, those who obtained permits to attend totalled 361, of a possible total capacity of 600.

The application process itself was complex. Judge Rif‘at had said in a press conference on July 31 that applications would open that day, and close at 4 p.m. on the next. With such a short window, there were still crowds outside the Ministry of Justice on August 2. The arrangements for getting a pass for the following days of the trial also seem to be intentionally convoluted, involving two separate courts’ procedures. More worryingly, Gamal Eid, Director of the Arab Network for Human Rights Information, complained that only five of his legal team were given passes, while the media got 99 and the Egyptian State Television alone a total of 93 passes. What was more, applicants would have to collect them on the day of the trial, picking their way through the crowds. In the end, security forces were in charge of admissions to the courtroom, and many of the meagre 361 were not allowed in. One of those kept out, former Deputy Chief Justice of the Court of Cassation Mahmoud al-Khodeiri, described applying in advance, and then seeing a cross by his name on the admission list.

This generated another disturbing scene once the trial had begun, that of the large number of civil rights lawyers, jostling for space and clamouring over the microphone to explain that only thirty of them were present, while over a hundred of their colleagues were stuck outside. Many in Egypt and abroad have commented since, calling the courtroom ‘chaotic’ and judging the lawyers ‘incompetent’. Some have seized upon these scenes to cast doubt on the entire Egyptian justice system.

Explanations, Obstacles Ahead

Commenting on the famed issue of the ‘chaotic’ scenes, legal experts have clarified that submitting written and verbal requests is the normal procedure in an Egyptian criminal court, and that observers are simply unfamiliar with the workings of the legal system.

On the question of the competence of the lawyers, this must be placed in the context of the vast difference in resources between the defendants and the martyrs’ families. To get some perspective, consider the defendant who was absent, business tycoon Hussein Salem: nobody has yet been able to estimate the total size of his fortune. He is currently being held in Spain for money-laundering, and is charged in Egypt with profiteering from ties with Mubarak. Salem built his Sharm al-Sheikh empire on vast swathes of state-owned land in South Sinai, and made over two billion dollars profit by illegally exporting Egyptian gas to Israel at prices well below market levels. Meanwhile, the Mubarak family fortune was notoriously estimated at 70 billion dollars in February 2011, bringing floods more of angry protestors onto Egypt’s streets at the time. Needless to say, the defense is able to afford the best paid and most experienced lawyers in Egypt, while the majority of the civil rights lawyers are representing victims from Egypt’s working and lower middle classes.

It is a bitter irony that most of those who braved the worst of Egypt’s police brutality in January and February were those least equipped to defend themselves legally. Khaled Abu Bakr, one of the civil rights lawyers, has explained that these people’s families, in the midst of such crisis, would reach out to lawyers they knew personally, and could not always afford the strongest legal representation. Compounding this has been a grave lack of coordination. Abu Bakr pointed out that the case in hand – which only relates to the events of 27 and 28 January – involves 848 victims, coming from six of Egypt’s governorates. With their families scattered across the country like this, coordination between their lawyers was a serious challenge, whether in terms of numbers, or joint legal discourse and strategy.

Yet within hours of the trial’s adjournment, a spontaneous campaign had got underway in Cairo to remedy this, supervised by Heba Raouf Ezzat, Lecturer in Political Science at Cairo University. The campaign aimed to strengthen the ranks of the civil rights lawyers, and to get in touch with anyone needing representation. Prominent lawyers such as Essam Sultan of the Wasat Party responded to the call, and a ‘Unified Front’ of lawyers has been formed since, holding coordination meetings daily. It is difficult not to wonder why figures like Sultan did not step forward earlier: the civil rights lawyers inside and outside the courtroom on August 3 did so well before the trial was confirmed, and before such media interest. One of these lawyers, long-time human rights activist Ahmad Seif al-Islam of the Hisham Mubarak Law Center, has pointed out that the issue most urgently requiring coordination next will be witness questioning.

It is important to clarify the role that the public prosecution will play as the trial unfolds, and the potential for coordination between it and the civil rights team. In the Egyptian justice system, criminal and civil cases are often heard together by the same judge. In the Mubarak trial then, the prosecution is concerned with proving the guilt of the defendants, while the civil rights lawyers are there to prove damage and seek compensation for the victims’ families. Finally, the Egyptian State Lawsuits Authority is dealing with the issue of squandering public funds: on August 3, its lawyer demanded compensation of one billion Egyptian pounds.

[Image from unknown archive]

One challenge facing both the prosecution and civil rights lawyers is the defence team’s manoeuvres to prolong the trial. On August 3, Mubarak’s and Al-Adly’s star lawyer, Fareed al-Deeb, requested to cross-examine 1631 witnesses for the prosecution, as well as all former governors of South Sinai and several other senior figures. The trial now looks likely to stretch to several months, and will soon overlap with the September preparations for the parliamentary elections. If the trial turns into a saga, it may well become overshadowed or easier to sideline.

However, contrary to their dismissal in some media, the civil rights lawyers made several important points when given their turn. Requests were made for a list of duty officers between January 25 and 28, for records of all phone calls made between the defendants during that time, and for the summoning of all State Security snipers to testify on the source of their orders. One lawyer also requested that representatives from the management of each of Egypt’s telecommunications companies be summoned as witnesses, to tell the court who issued the order to close down network services from January 27 until February 2. The next hearing, scheduled for August 15, will allow the court to hear from those civil rights lawyers kept outside and off television screens so far.

Beyond the Trial: Containing the Revolution

It is not just events in the courtroom that pose challenges to the quest to bring Mubarak to account. The ruling military council has presided over significant delay in the progress of legal proceedings against Mubarak, ever since pledging to try him in February. He was only detained after the Friday demonstrations of April 8 and subsequent sit-in, and he was only formally charged a month later. The public prosecutor had ordered Mubarak to move to Cairo’s Tora Prison hospital, but he was allowed to stay in Sharm al-Sheikh until his trial. The past six months have also seen several of Mubarak’s aides acquitted or escape charge altogether – including former Media Minister Anas al-Fiqi and Finance Minister Youssef Butrus Ghali respectively – while his sons and Habib al-Adly are rumoured to be enjoying five-star service and even sharing legal counsel at Tora. Doubts have been raised at the destruction of evidence under the army’s watch, after it emerged that the surveillance tapes of the Egyptian Museum from January 25 to 31 had been recorded over. On August 3, as the suspects left court, Egyptians were shocked to see several of them shake hands warmly with their military security guards, and Alaa Mubarak defiantly cover a camera lens in front of them. Yet the military council and government are now taking credit before the world for having held the trial at all.

In this sense, the Mubarak trial mirrors a contradiction defining the wider political scene in Egypt since January. On the one hand, there is abundant evidence of what appears to be collusion between the military council and members of the ancien regime. But on the other, SCAF generals assumed power on the pretext that they had protected, and would continue to protect the January Revolution.

First came the March referendum on constitutional amendments, which took advantage of people’s keenness to participate democratically, and produced a yes vote rather than an insistence on writing the constitution from scratch. In fact, legally, the 1971 constitution was void the day the SCAF took over. Soon enough, the yes vote was overtaken by 63 amendments imposed by the military council. Unsurprisingly, though this has not been made sufficiently clear, these contained provisions to enshrine the SCAF’s predominant position in new law. So article 51 created a vague ‘Defence Council’, its authorities unspecified, and most controversially, article 56 equated the powers of the military council with those of the president, leaving intact the associated extensive range of executive powers.

Since launching the transition period in this flawed way, the SCAF has at best been sluggish in the pace of reform, and at worst, worked to undermine the Revolution’s pluralist demands. It has employed crackdowns on strikes and protest, using violent tactics no different from those of the Mubarak regime, most recently in ‘Abbasiya and Tahrir Square. It has also displayed obstinacy on party law and electoral reform, and has formed a tacit alliance with the quietist portion of the Islamist movement that pledges loyalty to the military council. Most recently, the SCAF has used the state media to spread the line that any further democracy protests are selfish and frivolous, threatening the security, industry and tourism of Egypt. Turning public opinion against the revolution in this way is key to engineering a very controlled and limited change in the status quo.

What are the SCAF’s precise motives in this behaviour? Is it colluding with Egypt’s former rulers to protect them from retribution? There is no doubt that the Egyptian army’s senior command was in collusion with Mubarak the president: the SCAF are simply his former generals. General Tantawi and other senior officers in the council were loyal to their Commander-in-Chief and October War hero for years. However, the generals had also long resented Mubarak’s favouring of the police apparatus, which was key to his security system and enjoyed great privileges, over the military. The generals also chafed at the ascent of the civilian business wing of Mubarak’s elite, personified in his son Gamal, which threatened the military’s financial interests and its claims on the presidency. They therefore seem to have welcomed the revolution as a way to outmanoeuvre Mubarak and his son.

This said, the military council appears to desire a transition to a civilian government not unlike the Mubarak regime in terms of overall control, business orientation and collaboration, accompanied by deference to the military – Islamist politicians are useful allies in this regard. This is why, since February, the SCAF have employed calculated divide and rule tactics to contain the revolution’s impact, and dissipate its momentum.

Moreover, the military command’s record under Mubarak remains, and cannot be undone. In stalling Mubarak’s trial then, the SCAF generals are not so much covering for their former masters and partners, as for themselves. They are unwilling to open up a Pandora’s Box that might expose the extent of their own privileges under the old regime. The military was the first to take over state land in the 1970s and 1980s, using it to build and sell on public housing, as well as to launch business enterprises. The army has its own domestic goods companies, which sell to its personnel at subsidised prices. Under Mubarak, a substantial number of Governor positions in Egypt’s 27 districts traditionally went to the military. Senior commanders’ privileges also extended to priority treatment in luxury sites on the Mediterranean, many of which were purpose-built for them. Considering all this, allegations of corruption may not be so far away from the SCAF if this trial is allowed to get ‘out of hand’.

The same interests and fears link the SCAF to another set of actors: regionally, the Gulf monarchies, and internationally, the United States. The Gulf states were the swiftest to put down the uprisings on their own doorsteps: Saudi Arabia halted an uprising in Qatif province, and provided support and refuge to Ali Abdullah Saleh of Yemen. Its forces also fortified the ‘Peninsula Shield’ sent to put down the democracy movement in Bahrain. The Gulf monarchs have been disturbed by Egypt’s new foreign policy directions. This was particularly the case under its first Foreign Minister after the revolution, Nabil al-Arabi, who took firm stances on normalising Iranian relations for example, as well as on demonstrating solidarity with the Palestinian people, before he was moved to the position of Secretary-General of the Arab League. Meanwhile, Egyptian journalist Hamdi Qandeel has demanded that the SCAF investigate the raising of Saudi flags at the pro-SCAF Islamist demonstration of 29 July in Cairo. While some Salafi groups allege that these were simply the banners carried by Prophet Muhammad, Qandeel has raised pertinent questions regarding the political and financial influence of Wahabi groups over Egypt’s Islamists.

Since February, there have been growing signs of pressures upon the SCAF from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states, not to try Mubarak. Their monarchs clearly fear the implications of this precedent at home, in the wake of their own uprisings. They will also wish to avoid any revelations of their ties with the Mubarak regime, whether those of Saudi business and intelligence, or of the Al Saud, Al Nahyan and Al Sabah families on a personal level. When Mubarak suddenly issued a statement on April 10, it was on Saudi-owned satellite channel Al-Arabiyya and it seemed that Saudi elites were sponsoring his gamble to escape charges. This having failed, pressures from the Gulf will likely continue in line with the trial’s progress, and may well be connected to the financial assistance that was promised to Egypt by Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates after the high-profile Gulf tour of Prime Minister Essam Sharaf in April 2011.

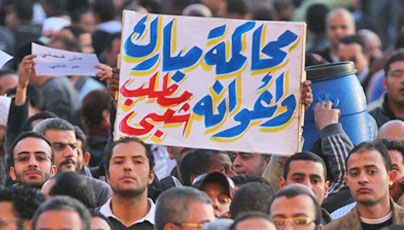

[Protester carrying a sign that reads "Trying Mubarak and his associates is a popular demand." Image from unknown archive]

Then there is the role of the US: it goes without saying that Washington has lost important allies in Zeinedine Ben Ali and Mubarak to the Arab Spring. But it has been quick to adjust and has found reassurances in the SCAF’s stances so far. America’s massive military aid to Egypt has generated close ties over the years between senior US officials and Egypt’s senior command. SCAF General Sami Anan shuttled between Cairo and Washington during the first January uprisings, and by March, Secretary of State Hilary Clinton had visited Egypt and blessed its democratic transition. There has been some friction recently over US funding for Egyptian NGOs, but these seem to be a side-issue in the broader context. While it is not easy to unravel the precise overlaps and differences in their positions, it is safe to say that the SCAF enjoys US support overall, and that the generals will safeguard any US-related information from revelation in the trial. In this regard, Washington’s public approval of the Mubarak trial in a statement on 4 August was telling.

The only regional state whose officials vocally lamented the demise of Hosni Mubarak on August 3 was Israel. As the trial got underway, Trade and Labour Minister Binyamin Ben-Eliazer told Israeli Army Radio that he had offered Mubarak asylum in Tel Aviv. He called Mubarak a ‘patriot’ for refusing to die outside Egypt, and added that he was personally saddened by Mubarak’s treatment at home.

Mubarak’s Defense, the SCAF’s Attack

Despite these multiple pressures then, the SCAF has failed to stall the trial any further. It is now caught in its dilemma between the need to undermine full transparency, and the need to preserve its self-image as guardian of the January Revolution. Since February, Egyptian politics has been characterised by a tug of war between the military council and the democracy movement, with the latter effectively using the SCAF’s proclaimed commitment to the revolution to extract concessions.

Now, Mubarak’s defense is playing upon the same contradiction, but in a different direction. During the first hearing, both defense and prosecution requested the presence of SCAF Chairman General Tantawi at the next hearing. The prosecution will wish to ask him precisely whose orders to shoot at demonstrators he so famously disobeyed. The defense, however, may ask other questions, intending to embarrass or expose the SCAF, perhaps inducing it to censor or reign in this trial somehow. Most controversially in the hearing, Al-Deeb referred to Tantawi as having ‘assumed control’ on January 28, well before Mubarak’s resignation was announced, thereby implicating him in events such as the camel and horse attacks of February 2. Indeed two days later, one of Mubarak’s lawyers alleged that Tantawi had been present, and Mubarak absent, at the meeting whose attendees decided to cut Egypt’s phonelines. A SCAF spokesman sharply refuted this allegation, but then a different lawyer in Mubarak’s team denied the original claim, fuelling the media controversy.

How will the SCAF react to this strategy in the longer run? Significantly, Mubarak’s trial only went ahead after the popular pressure exerted by the recent Tahrir Square sit-in and demonstrations held nationwide since July 8. The SCAF was compelled to begin the trial because of symbolic entrapment in a ‘heroic’ self-image. It is therefore highly unlikely to allow the hearings’ contents to erode this very image by exposing SCAF culpability in any crimes committed during Mubarak’s rule. Hence channelling public opinion toward indifference, impatience or outright hostility to the protesters, and more broadly to their notions of the demands of this revolution, is a crucial SCAF strategy.

Tactics include releasing agents of moral panic such as Islamic fundamentalists, and drumming up others such as the threats to security and national income allegedly posed by the Tahrir protests. The generals stayed away when busloads of Salafis descended on Tahrir on July 29 to declare their loyalty to the SCAF and to Shari‘a law. Days earlier, and without a hint of irony, the SCAF’s 69th statement had declared the April 6th movement an untrustworthy organisation for allegedly receiving foreign funding.

Another tactic is violence followed by outright censorship: the SCAF ordered the violent break-up of the Tahrir sit-in just two days before Mubarak’s trial and then relied on pliant media not to give this particularly critical coverage. One young lady who was beaten at Tahrir on August 1 – also the first day of Ramadan this year – gave her testimony at a public debate, because none of the private media channels she approached agreed to run her story.[1] SCAF control over the media was most dramatically illustrated when DreamTV television host Dina Abdel Rahman was fired by businessman Ahmad Bahgat, after she ‘talked back’ to retired Major General Abdel Moneim Kato in a live interview.

Meanwhile, state television images beamed to the world on August 3 highlighted the clashes outside the courtroom between those supporting the former president, and those involved in protesting against him. Since then, there has been a wave of television appearances by several of Mubarak’s cronies, competing to give their testimonies of January’s events on air. They have aimed to humanise Mubarak and portray him as a victim of misinformation. The overall intention is to depict the country as equally divided, and then try to make it so. However, it is more accurate to note that the majority differ over tactics, on how to run Egypt without Mubarak, but not on whether to do so. Privileging the more conservative trends in Egypt will be a prerequisite for a variety of possible SCAF actions: taking the trial slowly out of the public eye, limiting the information released in the name of national security with little opposition, and facilitating a plea for amnesty for Mubarak at the end. An alternative tactic could be to enhance the sensationalism in the trial’s coverage, partly to distract from the SCAF’s own poor record in fulfilling popular demands, but also to help invalidate the trial later.

Beyond the Trial: Advancing the Revolution

In the face of all these challenges stands the Mubarak trial’s effect in rejuvenating the consensus around the Revolution’s demands in several quarters. This was seen in much of the public debate in Egypt on and since August 3. In discussions, and interviews in the press and on the television, Egyptians of different backgrounds and political orientations expressed satisfaction at seeing the dictator on trial, and this within Egypt’s own justice system.

Some analysts have resorted to the term ‘show trial’, while others have expressed legitimate concern at the scapegoating that might result from an exclusive focus on retribution. Rather, what is needed is a systematic and public investigation into the workings of the old regime, in a way that facilitates the process of reconstruction by pointing in the direction of necessary reform, rather than indulging in a blame game.

In this trial, the outcome is as yet unclear and the process itself, which will be as important, is just beginning. So far, the performance of the prosecution and civil rights lawyers has not displayed undue sensationalism. The elaborate rhetoric of some may have seemed overdone, but others were simply keen to mark the gravity of their clients’ claims. The call for the establishment of truth and reconciliation committees might seem idealistic at the moment – no doubt they would flourish best under civilian rule – but the national debate has encompassed the main values and goals behind them. Many Egyptians distanced themselves from both Schadenfreude (shamata in Arabic) and vengefulness, stressing that they wished only to see a fair trial. A statement by the April 6th Youth movement echoed that a fair trial was key to establishing a new order in Egypt, one characterised by accountability and the rule of law.

Meanwhile, the brutality with which activists and martyrs’ relatives were cleared from Tahrir Square on August 1, and arrested in waves since, has brought the SCAF’s duplicity back into the limelight. Fifteen political movements and parties, some involved in the Tahrir sit-in and others calling for other tactics, condemned these latest violations in one voice. Activists have since reminded their audiences that the majority of the Revolution’s demands remain unfulfilled, from overhauling corrupt state institutions to ending military rule and the state of emergency. They have also signalled that they will be vigilant at attempts to use the Mubarak trial against the Revolution. They know that without their activism, there may have been a much longer wait for Mubarak’s trial, and they will watch any wrangling between the SCAF and Mubarak with caution.

Indeed, Mubarak’s trial opened against the backdrop of ongoing state violence against citizens not only at home, but in uprisings across the Arab world. While Egyptians’ protests grew daily outside the Syrian Embassy in Cairo, they expressed their pride at setting the important regional precedent of having brought their former oppressor to account, in a standard civilian court and not a military or special tribunal, and most significantly, by themselves and not as a result of US intervention, as with Iraq. In frequent comparisons with Saddam Hussein’s case, many highlighted the indignity of what was clearly a show trial by an American dictat, compared with the credible trial of Mubarak as a fulfilled demand of Egypt’s popular revolution. One opinion contrasted the figure of Saddam, his hair greying and standing tall, with that of Mubarak, still dying his hair and unable to stand up to his fate. As Mubarak lay in his cage, Syrian troops intensified their assault on Hama: to many in Cairo, the excesses of the Asad regime could only spell its downfall.

Since Mubarak’s ouster in February, analysts, politicians and activists have increasingly lamented that the Revolution has lost its focus, falling victim to divisive arguments on religion and stability. With the renewed attention paid to the second hearing this week, however, it seems that the Mubarak trial may yet restore the focus of the democracy movement, and test the credibility of the military council to its limit. The revolutionaries will have to be wary, however, of the SCAF brandishing the trial as the concession to end all concessions. In fact, this trial should only be the beginning, since it covers just two, albeit bloody, days in a period of state violence spanning weeks this year, and in a term of corrupt dictatorship lasting thirty years. Judging from the public debate, it has inspired and revitalised a large sector of Egyptian lawyers and rights activists. No matter the outcome of this week’s case, the repression, corruption and negligence that characterized the Mubarak era will surely generate enough trials to keep him caged for the significant future.