Kishwar Rizvi, The Transnational Mosque: Architecture and Historical Memory in the Contemporary Middle East (University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

Jadaliyya (J): What made you write this book?

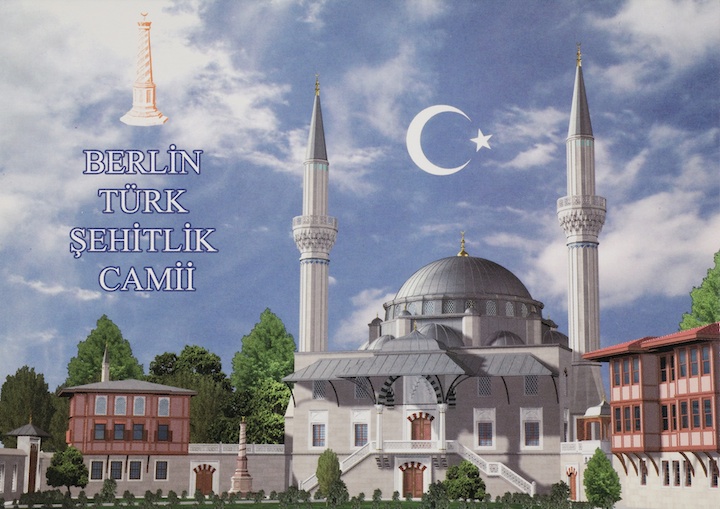

Kishwar Rizvi (KR): The idea for this book emerged through my research travels in Europe and the Middle East, where I would encounter monumental mosques that looked historical in design but were built in the past thirty years. I wondered why a community of immigrant Turks in Germany, for example, chose to worship in a neo-Ottoman style mosque that appeared anachronistic and out of place (see Figure One); similarly, why were mosques in Dubai copying the Mamluk architecture of Cairo (see Figure Two)? I wanted to better understand the motivations behind these stylistic choices in which reference was being made to particular moments in Islamic history. I wanted to know what the political and ideological agendas of the states sponsoring these buildings, namely, the government of Turkey in the case of the German mosques and that of the UAE in the case of Dubai, might be.

[Figure One: Türk Şehitlik Mosque, Berlin, Hassa Mimarlik, architects. Image via the author.]

I am an architectural historian and an architect. My focus has been on religious architecture in the early modern Islamic empires, as well as on issues of nationalism and politics in the modern Middle East. I have been interested in the manner in which the past is evoked as a source of inspiration and legitimacy, whether in Safavid Iran of the sixteenth century or in the Turkish Republic of the twentieth. Thus, when I was awarded a Carnegie Foundation Scholars Award in 2009, I wanted to understand the role played by history in the service of contemporary politics, and how it was manifested through the construction of monumental state mosques.

J: What particular topics, issues, and literatures does the book address?

KR: The book focuses on the intersection between architecture and historical memory in the contemporary Middle East. I study state-sponsored mosques to understand the political and ideological vision of four countries in particular, namely, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates. These countries represent, in many ways, divergent and complementary visions of state and society in the contemporary Middle East. I suggest that transnational mosques (defined as buildings built through government sponsorship both in the home country and abroad) provide insights into the diverse practices and beliefs of modern Islam and the nature of devotion in the twenty-first century. Their patronage, design, and production serve as important resources for understanding the role of architecture in creating public space as well as disseminating religious ideology.

The Transnational Mosque is based on extensive fieldwork, photo-documentation, and interviews with architects. Together they provide insights on several issues, foremost among them the centrality of history in the discourse on politics and Islam today; the transnational allegiances that divide and unite the Middle East and the world; and the place of architecture and the built environment in the performance of nationhood. This book builds on previous surveys of modern mosque architecture through theoretically focused and historically grounded analyses that aim to shed light on the intersection of religion and politics, and the transnational connections that it brings about.

J: How does this book connect to and/or depart from your previous work?

KR: I have written previously on nationalism and politics in the modern Middle East, with a focus on the Islamic Republic of Iran. I am interested in populist forms of religious authority and their co-option by nationalist agendas. In an earlier essay on the tomb of Ayatollah Khomeini, for example, I discuss the conflation of historicist shrine architecture with the symbolism of a state monument. I have also researched early modern (sixteenth-seventeenth century) architecture of Safavid Iran, in which I consider the social, historical, and urban dimensions of architecture. Then, as now, history and religion were motivating factors in imperial representation. Thus the new book builds upon my earlier work, while paying attention to subjects and sites that are new to me—namely, contemporary mosques and their transnational connections.

Religion has often been omitted from the discourse on art and architecture of the Middle East, as elsewhere, even though it is a central factor in contemporary politics and serves to both distinguish and unite communities of belief across the world. Thus The Transnational Mosque uses religious identity as a starting point to understand how countries in the Middle East construct, and export, their national image through the patronage of state mosques. I also situate these buildings within the context of architectural history and theory, positing that the roots of historicism lie in the postmodern movement, which sought to legitimize classicism as an antidote to modernism, looking at historical form for design inspiration and, often, direct imitation.

J: Who do you hope will read this book, and what sort of impact would you like it to have?

KR: The book was written with a broad audience in mind, from architectural historians to students and scholars of the Middle East, from architects and practitioners to those interested in urbanism and cultural studies. I hope that the book is visually rich and accessible, challenging readers’ preconceptions about political allegiances in the Islamic world, and the mutability of identity in the contemporary Middle East.

[Figure Two: Jumeirah Mosque, Dubai, Hegazy Engineering Consultants, architects. Image via the author.]

I have had the opportunity to share my work with diverse academic and design communities in the US and the Middle East, and it has been rewarding to see how people engage with the material based on their own geographical and political locations. I hope the book initiates conversations on these state monuments and their role in creating (or negating) public discourse; their centrality in national and diplomatic agendas; and their place in contemporary design practice.

J: What other projects are you working on now?

KR: A new project that extends the findings of The Transnational Mosque is on the relationship between state mosques and international museums, focusing on Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Both countries have invested a great deal of financial capital in the construction of monumental religious and cultural institutions; however, they are often viewed as distinct and unrelated. In my study, I consider the “soft power” of the museums and mosques in the construction of national identities in the Gulf as two sides of the same coin, catering to citizens as well as a global community.

Excerpt from The Transnational Mosque: Architecture and Historical Memory in the Contemporary Middle East

Transnational mosques provide insights into the diverse practices and beliefs of modern Islam and the nature of devotion in the twenty-first century. Their patronage, design, and production serve as important resources for understanding the role of architecture in creating public space as well as disseminating religious ideology. The networks within which contemporary mosques exist are more complex than ever before and need to be studied within their political and historical contexts. Their symbolic meanings and formal relationships, however unique and specific to the Muslim context, also connect them to modern architecture from other religious traditions. Contemporary mosques thus mark the underlying connections, sometimes harmonious and sometimes in conflict, within the modern Middle East in particular, but also the world at large.

In the twentieth century, architectural production in the Middle East, as elsewhere in the developing world, was predicated on emulation and engagement with Western forms of modernism, in which emphasis was laid on projects that furthered the image of statehood, such as educational and governmental buildings. Seen as derivative of movements in Europe and the United States, this architecture was often considered by scholars to be neither indigenous nor international, belonging neither to Islamic cultural history nor to the history of global modernism. Even less attention has been paid to modern religious architecture, such as mosques, shrines, and community centers, which are dismissed as catering to popular taste and undeserving of intellectual engagement. It is necessary to question these presumptions by studying the nationalist roots of early twentieth-century architecture, as well as the impact of international modernism on the built environment of the Middle East.[1] It is also important to investigate the manner in which such institutions may be viewed as forms of political and social agency.

I assert the heterogeneity of Muslim identity by focusing on distinct mosques and by revealing the complex negotiations that take place within and between nations and communities of belief. Recent scholarship has laid important groundwork for understanding the networks through which these negotiations are implemented.[2] Architectural practice at the turn of the twenty-first century, too, is one of interconnections, predicated on the itinerancy of architects and the global networks of corporate construction firms. Identities and nationalities can provide access, as is the case of the young Lebanese-American-French architect Michel Abboud, whose practice is located in New York, Beirut, and Mexico City and who was commissioned in 2010 to design the Park 51 Islamic Cultural Center and Mosque in lower Manhattan.[3] Similarly, the London-based Halcrow Group oversaw the construction of the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi. The ability for individuals as well as corporations to move beyond geographic borders and even religious ones speaks to the transnational nature of contemporary architectural culture and the mobility provided by modern technology.

The regional interconnectedness of modern architecture in the Middle East is a subject that has not received the attention it deserves. Most studies focus either on a specific nation or generalize the motivations for all Muslim communities. The study of modern mosques often falls into the latter category and, despite attempts at exhibiting diversity, results in essentialist readings of a pan-Islamic identity. The first comprehensive examination of modern mosques was published in 1997 and divides the subject into categories such as governmental and individual patronage, community and commercial institutions, and sites in Europe and the United States. One of the categories relevant to this study is that of the state mosque, which the authors, Renata Holod and Hassan Uddin Khan, define as “a building initiated by the central government and paid for by public funds. It is inevitably conceptualized by a committee with an insistence upon a clearly recognizable image, that is to say explicit in terms of regional, modernist and Islamic references.”[4] This book builds on the foundations laid by that earlier scholarship by focusing on transnational mosques built within and beyond state borders.

In the past forty years, religious identity has come to play an increasingly central role in public discourse. This is evident in the Islamic Republics of Iran and Pakistan, but also throughout the Middle East and South Asia, where Islam is a galvanizing form of sociopolitical expression. New patrons promoting religious ideology as a source of political agency have sponsored wholesale reinterpretations of traditional building types. Similarly, greater emphasis has been laid on institutions that represent and augment Islam, such as mosques, madrasas, and community centers. Contemporary mosques employ tradition as a starting point for their design, but their styles move beyond the simple repetition of form. Not only are older motifs reinterpreted, but the very functions of a mosque are altered in order to respond to social change. A cogent example is the Kocatepe Mosque in Ankara (Figure Three), a massive structure with a parking garage and shopping mall in its lower levels, which looks strikingly like Ottoman mosques built in previous centuries. However, here the patron was not a sultan but the populist Welfare Party (Refah Partisi), with its appeal to a broad segment of Turkish society.

[Figure Three: Kocatepe Mosque, Ankara, Tayla and Uluengin, architects. Image via the author.]

Architecture emerges as the repository of historical consciousness, serving as it does to both monumentalize belief and situate it within particular geographic and ideological sites. Although a building like the Kocatepe Mosque may have a singular physical location, it will arguably reference places far removed from Ankara and moments remarkably distant from its date of construction. This mobility marks contemporary architectural practice and subverts ideas of regionalism and nationalist styles that have pervaded the discourse on architecture in the twentieth century. Mosque architecture, in particular, also calls into question the common representation of Islam as a monolithic identity, shared across centuries and continents. Instead, examples of contemporary mosques require contextualization, even as they highlight the transregional and transhistorical trends that define architecture and religion today.

As current events in the Middle East and North Africa demonstrate, allegiances in the Islamic world are often based on the perception of shared histories of language, ethnicity, and religion. However, the term “Middle East,” while suggesting a category of affiliations, may better be understood as an umbrella under which diverse histories, politics, and religious identities are gathered. It is useful to think of this seeming territorial designation instead as a “geopolitical concept” or a “virtual space” that serves to unite shifting social and political realities. As Michael Ezekiel Gasper writes, “The Middle East belongs to a geographic imaginary that is in part built on the general alignment of contemporary geo-strategic power. Accordingly, it will inextricably accumulate new meaning until some major strategic realignment occurs and the geographical paradigms that have been in place for more than a century give way to something new.”[5] Despite the too-simple discourse of globalization as a boundaryless web of correlations, the reality of the early twenty-first century is that identities—such as “the Middle East” or “the Islamic world”—continue to dictate how people and their governments define themselves.

Architecture, particularly that of mosques, manifests territorial as well as ideological connections by referencing historical periods and building styles and by enabling the rituals of inhabitation that augment the practice of religion. It may be argued that among the most important issues connecting—and, unfortunately, sometimes dividing—the Middle East is religious identity. While this identity is constructed and disseminated through several national and subnational means, four nations represent important, and distinct visions, for the future of the larger Muslim community, and are taking steps to advancing that agenda. Thus Saudi Arabia, Iran, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates serve as the starting points of this study. Through close analyses of their nationalist projects and their patronage of transnational mosques, valuable insights may be gleaned into not only the region’s political geography, but also its architectural landscape. Through their patronage, the dynamic mobility of form and meaning is made manifest. Rather than suggesting any predetermined flow from one to another, the mosques studied here reveal the unexpected and complex interactions between these nations and global communities of belief.

NOTES

[1] Rizvi and Isenstadt, Modernism and the Middle East (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008); Rizvi, “Religious Icon and National Symbol,” Muqarnas: Journal of Islamic Art and Architecture 20 (2003): 209-224.

[2] Cooke and Lawrence, Muslim Networks from Hajj to Hip Hop (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

[3] The program has since been changed. The current proposal calls for condominiums and a museum of Islamic art, the latter to be designed by the French architect Jean Nouvel.

[4] Holod and Khan, Mosque and the Modern World (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997); 63.

[5] Gasper, “There Is a Middle East,” in Is There a Middle East? The Evolution of a Geopolitical Concept, edited by Michael E. Bonine, Abbas Amanat, and Michael Ezekiel Gasper (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012); 240.

[Excerpted from Kishwar Rizvi, The Transnational Mosque: Architecture and Historical Memory in the Contemporary Middle East, by permission of the author. © 2015 University of North Carolina Press. For more information, or to purchase this book, click here.]