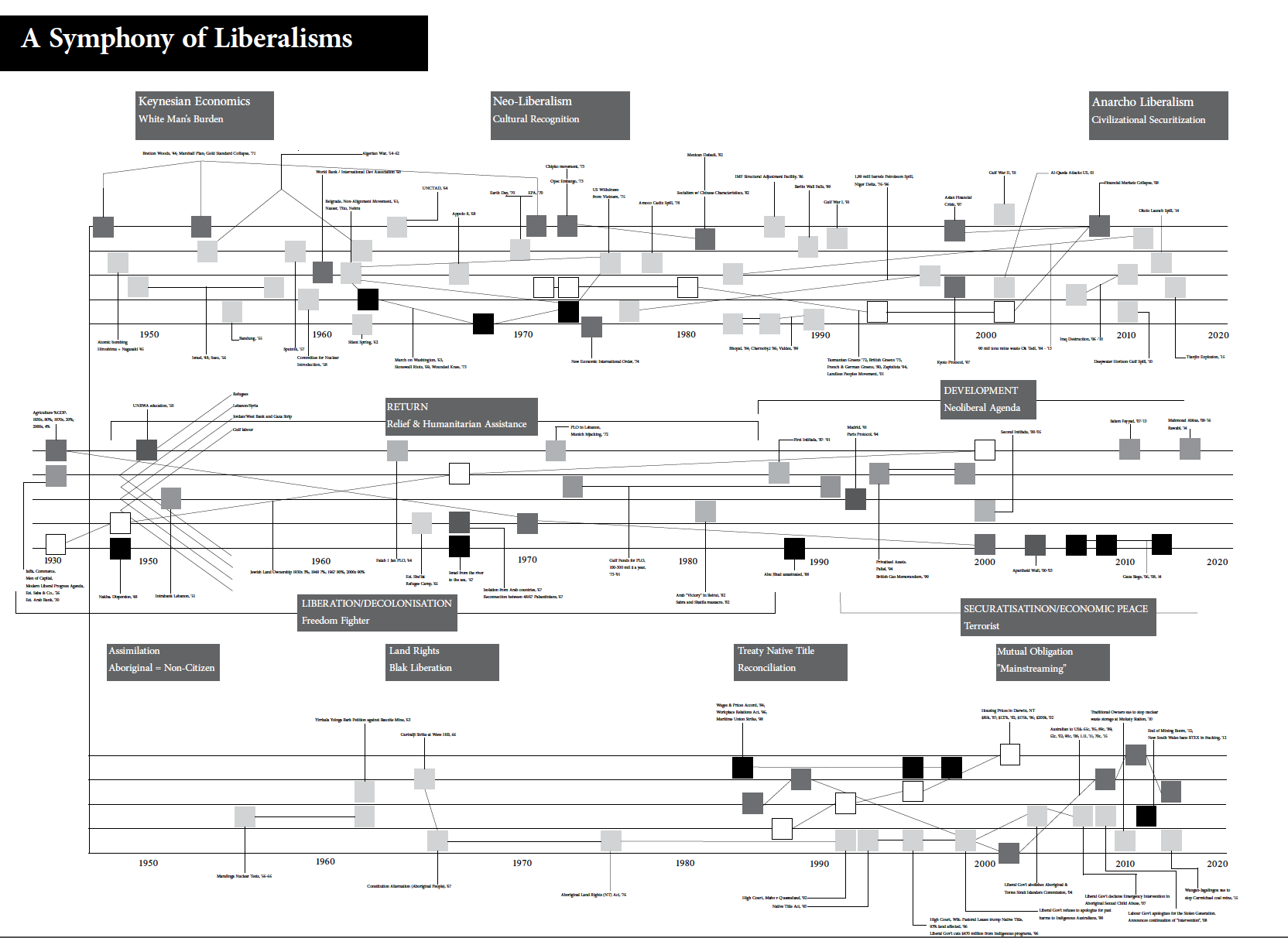

The great events of history tower over Jerusalem, almost as though they were unappeasable lords. But what if “history” were understood not by its crowning moments but by its sinews, as a narrative texture that warps through the media of populations and territories, articulated not in grand declarations but in the everyday fact of decision-making and the minor economies of daily life. This is the base proposal of the Symphony of Late Liberalism, a concept-image by Elizabeth A. Povinelli, and recently featured as part of the 8th Jerusalem Show, commissioned by Al Ma’mal Foundation for the 3rd Qalandiya International.

The Symphony was initially posed in Economies of Abandonment (Duke University Press, 2011) as a critique of liberal philosophy’s attachment to “the event” and of its role in the material deprivation of indigenous societies through the temporal divide of “now” and “then” across which the settler colony asserts its claims. More recently, in this year’s Geontologies: A Requiem for Late Liberalism (Duke University Press, 2016), the Symphony was expanded as part of a more fundamental critique of the teleologies of the biopolitical era amid the time of their unraveling as a Euro-centric political logic, and in the face of climate change as an inadmissible force.

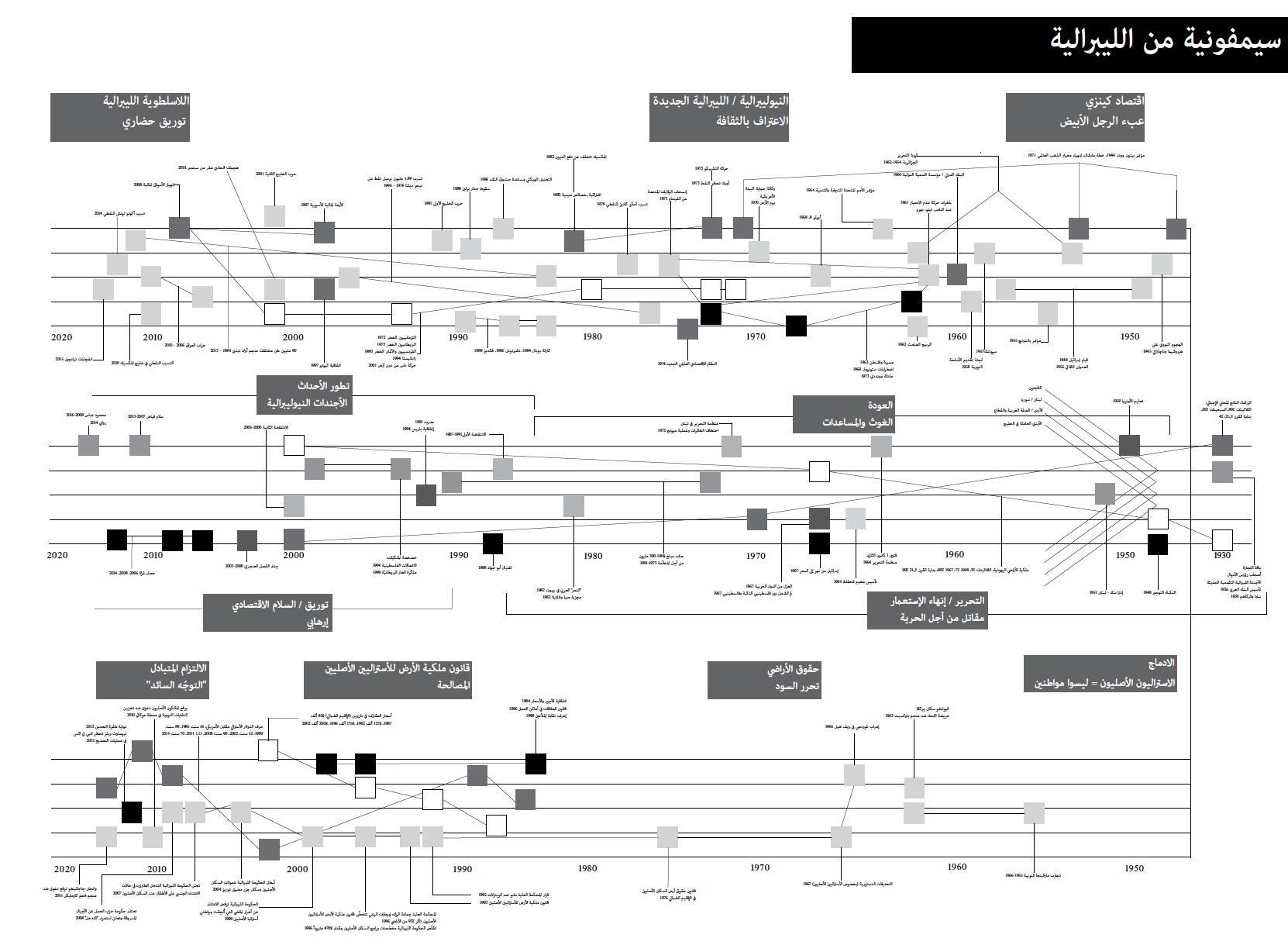

For the 8th Jerusalem Show, a revised edition of the Symphony was commissioned with a new third stanza inserted, devised in collaboration with Political Economist Raja Khalidi. Transposed into Arabic, the Symphony was installed as a wallpaper in Jerusalem’s Gallery Anadiel, along with the most recent film by the Karrabing Film Collective from Far North Australia (of which Povinelli is a member), and a series of paintings of current strife in Burma by Shan minority artist Sawangwongse Yawnghe.

[Click image to view high resolution version]

[Click image to view high resolution version]

The installation was part of the 8th Jerusalem Show’s broader study of the 3rd Qalandiya International theme of Return, undertaken through the double-exhibition Before and After Origins. Considering 1948 the “origin” of the Palestinian project of Return, the Symphony was a key element in the half of the exhibition that was under the title of “After” and that sought an “arts of connection” amid prevailing conditions of isolation and the enforced separation of security industries.

The presentation was the second time the Symphony had been installed as a graphic work within an exhibition having featured earlier in 2016 within the first edition of Frontier Imaginaries, a roving art project led by Jerusalem Show guest curator Vivian Ziherl. As a conceptual plotting of the advancement and transformation of globalizing power relations, the Symphony is mobilized in these exhibitions as an aesthetic device by which to chart ongoing technologies of neo-colonial dispossession and the social projects that resist them.

In its latest edition, the Palestinian stanza sounds out the local tune of the greater post-War symphony. At the same time it also modifies the leading melody as events that were imperceptible from the Australian/Indigenous horizon appear within the global stanza. What emerges is the dissonant condition of Palestine’s imperfectly aligned rhetorical, economic, and territorial spaces, along with their changing bearing in relation to the state and non-state actors of the global realm. In the following interview, conducted on 15 November 2016, following the 2016 US elections, Khalidi, Povinelli, and Ziherl tease through the many resonances of the Symphony in its Palestinian edition.

Vivian Ziherl (VZ): Let us start at the beginning.

Raja Khalidi (RK): Why a symphony and why liberalisms?

Elizabeth Povinelli (EP): In Economies of Abandonment I used the phrase late-liberalism to describe a topological twist in the governance of difference—the emergence of a new tactic of the liberal governance of difference around the late 1960s and early 1970s usually referred to as liberal forms of social and cultural recognition or state multiculturalism. We were not seeing a break or a rupture in liberalism but rather a re-alignment of a strategy of governing difference. By the time I got to Geontologies—actually by the time I published Economies of Abandonment—I began using the phrase late liberalism to indicate a topological twist in the governance of difference and the governance of markets. Neither form of governance determinates the other, nor do either of these forms emerge simultaneously or homogeneously across the globe. That is why I am not saying Symphony of Capital, nor am I saying Symphony of Liberalisms per se—to say either of these would indicate that the one or the other is the determining structure. And that is why in the Symphony there is not a time or a place where late liberalism happens. Instead late liberalism happened and is happening. It happened because, under the unrelenting pressure of anti-colonial movements, new social movements including Black Power movements, Red Power movements, Radical Feminism, the Queer movements, etc. the way liberalism governed difference underwent a serious legitimacy crisis. That whole civilizational rhetoric in its multiple forms just does not fly anymore. Running parallel to this crisis was another—the failure of Keynesian economics. Thus the Symphony shows the unfolding movement of late liberalism across the two axes of crisis in the governance of difference and the governance of markets.

RK: Neither of which are compatible or have been able to align themselves with pure market fundamentalism?

EP: I think that’s right. They do not fully align themselves with each other, nor do they fully align themselves with market fundamentalism, meaning even the governance of markets in so-called neoliberalism was never pure Hayekian liberalism. That is where the recent US election—but also Brexit and Le Penism—is interesting for me. Each election has a very different national context even as all of them are marked by a rebellion of white working class populism against financial global capital—in this case a white working-class populism is rebelling against the late liberal governance of difference and markets. But, again, I do not see the governance of difference and markets composed of the same logic or in a base-superstructure relationship.

RK: They are dissonant in your vocabulary.

EP: I think we going to see a topological twisting here, yeah, so not autonomous but also dissonant.

VZ: So, how would you answer these Raja?

RK: This is totally alien to me. Firstly I understand the Symphony as an attempt at a graphic representation of the sonic and I do not hear the sounds, or can not read the notes. I understand the representation chosen (of Global and Local/Aboriginal). And now that you have added a Palestine dimension to create three stanzas, you can have ten, you can go around the world with this Vivian and you can add a few more at least.

EP: I chose this graphic form to indicate that there is something about the movement of power and its formations that is not equivalent to logos and its formations, that is to reason, explanation, propositionality, concept, and rhetoric in a linguistic sense. I was thinking about the sonic as one of the conditions and rebellions of the demos against logos.

RK: Do you hear it when you look at it?

EP: Yeah I hear it. I have never had it played and I think it would sound less than melodious but that is my point. The sonic force of governance does not correspond to the rationale of logos. But the second thing is that the top bar, in the way in which I conceptualize the Symphony, is not static: the top bar is written from the bottom bars’ perspective.

RK: Sure sure sure, but I think the basic movements and intellectual currents of the events that are in that global bar are universal of course. I guess that the differences in directions and flows that will be found lies in these forces’ divergent regional penetration around the world and in areas of life. In the Palestinian context the global stanza (as conceived by the composer) is not something we have really been aware of or considered as influential in our lives. I think the Palestinians like all peoples have obviously been affected by these global currents but have not really interacted with it in the way that say Israel has. In fact, if you were to compose this symphony from an Israeli perspective, a settler colonial’s perspective, there would be a lot more harmony and sort of synergy even, between the two (global and Israeli). Not in a conflicting way, in a harmonious way let’s say. Whereas you know the Australian Aboriginal and the Palestinian subject to settler colonialism vantage point…it works or performs inversely to the manner in which a hypothetical Israeli one would. Because it is always in the context of resistance to the settler colonialism

But we all know that settler colonialism is not a local phenomenon, it is part of that global stanza, it is one of the offshoots of it if you will. It is one of the essential bars on that stanza. Sitting in Palestine today as a political economist, sure I can see how the advance of liberalism and the advance of capitalism and globalization etc. have had a major effect on the ability the resist and on the forms of resistance. Now everybody is talking about “cultural resistance,” that is what Vivian was in Jerusalem for, this is what we are doing now, it is a form of “cultural resistance.”

In any case the national has always trumped the “social” in the Palestinian context at least since there has been a national liberation movement after the 1960s. But do not forget even before that there was an anti-Zionist, anti-colonialist movement, which basically means since the end of the first World War. That is why I argued with Vivian to extent the Palestine bar to prior to the First World War because I think that is in fact where the origins of the Palestinian symphony lie, at the end of the Ottoman Empire before Zionist colonization arrived in any major sort of way. I think there was a lot more in common between the issues and problems that Palestinian Arabs and Syrians and other Arabs faced, similar to those in other developing (post colonial) countries in Asia, Africa, face, than there are today. So that is where the divergence in our experience from many others’ began. The social and the economic have always been trumped by the national. Elites have gotten away with murder if you wish in that vacuum, because the social is postponed until the day of liberation. That has been the narrative and people have stuck to that. Only recently I think in the last five, ten years, has it started to fall apart because of the failure of the national and the mitigation of the social and the economic.

EP: Right. Just to underline an interesting difference that emerges if we were mapping out the national and global spaces of these stanzas in the contexts that Raja was discussing: at least in the Australian context demands for social and the economic justice were not postponed until the day of liberation. There certainly have been various nationally based struggles among various Indigenous movements. The Red and Black Power movements were very influential on a group of Australian Indigenous activists in the 1950s and 60s. But the Australian Indigenous struggle for land rights were in large part ignited by a wage dispute that led to the 1966 Wave Hill walk-out led by Vincent Lingiari. Moreover, a host of contemporary Indigenous thinkers insist that social, economic, and land based movements cannot be disarticulated because they internally belong to each other as the condition of each other. I am thinking of Aileen Moreton-Robinson’s work here. In the Native Americas, nationalism and the imaginary of sovereignty has certainly shaped anti-settler discourse insofar as many Native Americans call for a return of unceded sovereignty to their lands and modes of life, but sovereignty itself has also been seen, and is definitely now being seen as a Trojan horse by theorists such as Glen Sean Coulthard and Audra Simpson. They are arguing that the struggle over sovereignty is one way that the liberal governance of difference works to contain the difference of Native forms of belonging within settler colonial reason. What would an Indigenous national liberation project be outside the liberal imaginary of the nation and sovereignty?

RK: We are in different phases, Beth. In our case it is continuously postponed. In the two cases of the Native American and Native Australians, you are talking about anti-colonial movements and processes of decolonization that have effectively been abandoned for over a century if not more. I mean, when was the last organized, mass, or armed resistance for national liberation by indigenous peoples? Maybe Zapata or Chiapas in Mexico? There have been movements of Indigenous peoples in parts of Central and Latin America of course and they continue until today but they are not really about national liberation: they have been transformed by liberalism as well as by humanitarianism into different sorts of ethnic or class struggles.

The point is, it is only recently that social issues have come to the fore in Palestine and I would say not even yet in the form of a social movement, because there is still this claim that we are pursuing national liberation. I had this discussion with somebody yesterday who mentioned “‘since we’re still in the stage of national liberation…” and I said “excuse me, by process of national liberation do you mean ‘state-building?’”

EP: [chuckles]

RK: That is the standard trope! So there is this claim and there is reality too. There is still a huge part of Palestinian population that believes in continued struggle and resistance, including even armed resistance. Not only resistance, but ultimately many, if not most, accept that this is a struggle that could go on for another generation or two if need be. So I do not see that same national identity or national liberation dimension in indigenous peoples’ liberation struggles. When was the last conscious, organized attempt at resisting settler colonialism in the USA? Perhaps the American Indian Movement? Or the Black Panthers?

EP: But I’m not even sure I would say that it was national liberation equivalent to the Palestinian case. Which is really interesting.

RK: I have been thinking recently that we really are in a post-national moment here. We have to recognize that and we haven’t recognized it. What is nationalism beyond a nineteenth century right wing, even xenophobic political relic . . . What the hell are we doing pursuing nationalism in the twenty-first century, as the “last occupied nation?” We have got our national identity so let us move on, but let us see what rights we do not have. In that sense the Indigenous peoples of America and Australia and elsewhere have accepted the realities and have also gotten a head start on us in terms of some defining of their position towards markets and capital and so forth.

EP: And each other! So how do we think about forms of belonging that don’t always rear-end into sovereignty as contained within the imaginary of western self-determination within or outside a national framework or nationalism per se. And really smart young Indigenous thinkers and activists are trying to work on Native belonging against western sovereignty and nationalism.

RK: People always look at me—“comrades” in the left as well—somewhat askance when I mention this, because they have a brand of radical socialist nationalism, that really needs the idea of a continued national struggle of the Palestinian people for national self-determination. So when it is suggested that maybe a better way to achieve the social agenda that Palestinians espouse is through pursuing that and thereby consolidating what we have achieved in terms of a national identity, rather than seeking more national self determination in a context that absolutely denies it, some left nationalists take that as heresy because I appear to be advocating abandoning the national struggle. You must agree with me, you are sitting in New York, you can see, the Palestinians are there. They are out there, we have clearly established our national identity globally (and among ourselves and our Arab “brethren”) even if we have not secured sovereignty, independence, or banished settler colonialism.

EP: Yeah, that is right.

RK: Symbolically, politically, diplomatically, and institutionally. So there is something else missing.

VZ: One of the things that comes up in the recent crises of liberalism vis a vis Brexit and Trump is the difficult question of how much the racial is an embedded category of capital itself? For you Raja, it was necessary to take the Symphony back into the 1930s and to capture the era of Jaffa “men of capital.” What was taking place there? Was it an Indigenous form of capital that was being practiced?

RK: Absolutely, and I think that is where we go back to this question of the national trumping the social and that started really then. Because that’s the moment at which Palestinian capital and economy in society started really not only urbanizing but shifting from a more primitive mode of production, an agrarian economy, to an industrializing, commercialized (capitalized) economy. And so of course these businessman and commercial capitalists largely, but also eventually industrial capitalists and finance capitalists, began to assume a position in the national leadership again. All these new players were subsumed to intellectually and socially (class) inferior if you wish, or culturally less educated, less wealthy political and national leaders. So the Husseinis (and other notable families) in Jerusalem who led the Palestinian national movement from the Ottoman times, through the mandate and until the Nakba, were not men of capital. These were men of politics and feudal landowners, officials and agents of the Ottoman regime etc. appointed as sort of an aristocracy of a political elite that aligned itself with the men of capital in the 30s, whose issues and potentially transformative role was basically subordinated to the national movement at that time.

I have a running argument with my colleague Sobhi Samour about the role of patriotic national bourgeoisie, and whether such a thing even exists. And can there be a progressive wing to it? And this takes you into Leninist thought, Maoism and other third world theories, Fanon of course is the master of this discussion. But basically, the question remains as to whether capital aligns itself with the national liberation struggle and subordinate its interests to that struggle? And at what point does the tension become too great, and whether that is what we are seeing now in Palestine, at what point does capital start dictating the terms of the national?

VZ: We see over the Symphony a pretty strong periodization of a Keynesian post-war phase that moves into a neoliberal one. But Raja, do I understand from you that what has mattered to the Palestinian stanza is its internal dynamics as opposed to the broader prevailing trends?

RK: Definitely. Remember Vivian when we talked about the direction of some of the trajectories or even the direction of the Palestinian trajectory of the bar, the stanza, compared to the other ones? This echoes what Beth was saying earlier about the nature of the struggle of Indigenous peoples and the actual political, social and economic content of their demand as compared to the Palestinian peoples movement. Whereas I see the rationale and logic of the periodization and the fact that there are two horizontal lines and that the Australian one is parallel and below the global trend is coherent. It makes sense because those struggles in Darwin etc. were very much linked to Keynesianism moving to Reaganism, moving to neoliberalism, moving to whatever, financialization in recent years for example. They were direct outcomes, maybe they are not causally linked, but they definitely mirror. They correlate with those global developments.

However—because of what I said about the Palestinian trajectory being one until today at least, of national liberation before the social, before the economic, before the struggle between labor and capital—the Palestinian one may be better conceived as diagonal to the two. Because it draws on and is influenced by one—the global—and feeds into the other—the indigenous—but is not really parallel to either. Things are not happening in Palestine either periodically, sequentially or dialectically in the same way.

EP: Totally, they are right parallel. I really like the idea of the diagonal, because part of what’s at stake is the sliding across the “governance of difference” and the “governance of markets” and also across the geographies in which each is being elaborated. Where do these forms of governance land or not, when, and in what form? Is there a form or—and I would argue this—only a series of more or less “kind of like that” iterations? If we think of late liberalism as fundamentally diasporic and geographic, how might we see time go backwards as much as forward as the forms of late liberal governance move across space? So even neo-Keynesian neo-liberalism starts ramifying in the Australian national context much later and in a different from than in the US and England. The particular Keynesian arrangement among the Australian state, capital, and the labor movement (the “Labor Accords”) persisted far later than they did in Europe, or the US.

RK: Regarding the race question: in our case, what is race? We look through the prism of settler colonial occupation. So when we look at that, there is the white Ashkenazi settler, but there is also the Falasha Ethiopian, the Arab Jewish settler colonial. In a sense, I don’t think that in any way, either the national problematic or for sure not the capital or class problematic is in any way related in the Palestinian context to race. But I can see why it is in the case of Australia or the United States.

EP: But here that becomes a really interesting question for me. When we start thinking about race and capital you really have to extend the bar back a long time. Certainly prior to Marx, and prior to what Marx describes as primitive accumulation. Already by the time CLR James and then Sidney Mintz are discussing primitive accumulation it has come to refer to the extraction of life and labor under the sadism of slavery in the New World. So primitive accumulation as the condition for the emergence of capital per se does not start in Europe. It begins in empire and colonialism, in a form of the governance of difference wrapping around race and settler colonialism stretching between Europe, West Africa (and beyond) and the Americas. Primitive accumulation provides the condition of capital by a sadistic extraction of life and labor. So then you accumulate enough for “North” or “Western” capitalism to jump start itself. But a host of Indigenous theorists, and especially Glen Sean Coulthard in his book Red Skin, White Masks, are now saying, “let’s not talk about primitive accumulation, let’s talk about original accumulation.” And here the axis shifts from the extraction of life and labor, to the dispossession of land and the extermination of life; and the abstraction of land from the conditions of social belonging. Original accumulation has a different axis of sadism, a different modality of genocidal labor. If primitive accumulation sucks the life forces from certain bodies to produce surplus value for others, in original accumulation certain bodies are in the way of others and must be disposed of.

RK: Primitive accumulation was something that Marx was using very adeptly for a stage of industrialization that maybe has now moved on. And I was very interested listening to what you said about original accumulation, almost as if you were talking about the Zionist-settler colonial context.

EP: The argument that he is making and a lot of us are making is, it did not happen, it is happening. In the Zionist context and the Indigenous context.

RK: And as you said, the idea of dispossession of land and/or expulsion from space is going on all over the world. I mean look at China. I have been thinking about something every time I drive past a settlement. Imagine from the Zionist capitalist point of view, what a good deal this country has been: you inherit land resources which are valued at millions of dollars per square kilometer. I would love to be able to figure out the actual value of the land that Israel has put its hand on or has taken over or is exploiting or is preventing Palestinians, not to mention the water resources. But imagine building these settlements, being able to sell these settlement villas for hundreds of thousands of dollars. It must cost them nothing! You get free land, you get free infrastructure and all you need to do is bring in the tractors and the stone-masons! It just creates capital, it accumulates capital in an extraordinary way. Not in an efficient way of course: this is the most highly subsidized capitalist settler movement in the world.

EP: Right, because if we’re going to talk about race, then in certain settler contexts the politics of dispossession might align the settler nation with capital. What a great deal. But in the US context, what we have is somewhat different. First the settler imaginary is shot through with a racial imaginary, Native genocide with the sadism of slavery. Non-Native Americans don’t inhabit a settler imaginary in the way that whites in Australia and Canada. Settler Australians and Canadians can’t help but confront the fact of settlerness. Non-Native American populism is different. US populism is racialized such that the angry white nationalism want the “wages of whiteness” (Dubois; Roediger), but to get these wages they think they need to turn toward a national capitalist—that is businesses, corporations who are understood to be either nominally or fully American—and away global financial elites. Or more profoundly like the Brexit, turning away from the global capitalist: that is the wages I get from being white—in another context we would say the wages I get for being a settler—are now not paying the dividend that they properly should be paying based on our having dispossessed both in an ongoing and primitive way. That’s what I’m finding really interesting in the US context and in the European context. That the settler, although in America wouldn’t self identify himself as settler, is now not reaping the rewards of the great deal anymore. So again in the Israeli context, the Zionist are still “this is great, I love being the settler.”

RK: Do not forget, they definitely don’t define themselves as settlers.

EP: White American folks don’t define themselves as settlers.

RK: But they did probably until they completed the settlement, no?

EP: Well, no. That is so interesting about the American context. In the shocking aftermath of Ronald Reagan`s election in 1980, critical theorists sought to understand how a large bloc of the white middle class voted “against their interests.” Some political scientists pointed to Reagan`s expansion of Nixon`s southern strategy to the Midwest, such as Lee Atwater for whom the explicit racism of the Nixon years gave way to the racist dog-whistles of “welfare queens” in Reagan`s campaign. What white voters wanted to hold onto were the wages of whiteness, they desired to be a part of a white upper class that they no longer could securely hope for. Desire for status trumped their structural interest, or as Gayatri Spivak argued, interest and desire are separate conditions that can be aligned or not according to the international division of labor. The resonances with Trump`s rise and win of the Electoral College are obvious. But what is not obvious is what do white people want and what is their interest in the current arrangement of globalized financial capital. Our national populism—there is tons of great histories on this—in its core is defined by whiteness. And whiteness as opposed to blackness.

RK: Correlated with or defined by?

EP: Defined by! The Southern strategy of the Republican Party from Nixon onwards mobilized the definition of populism as white. The Southern Democrats understanding that American populism was built on white identity, shifted and realigned the party according to that middle class white identity and basically thought that blacks and the poor would have nowhere else to go. So they assumed that as their voter base, and they rebuilt the party around the white middle class. And that’s because the American relationship to slavery has been so formative in crucial ways it’s displaced the settler imaginary for them. That most Americans don’t think about America as a settler colony. It’s way in the background. The contortions of whiteness, settlerness, capital, in some ways are more weirdly mobile than I think in Canada and Australia.

RK: At what point does a settler no longer become a settler? I would have thought for a lot of people, moving West was not colonialism. It was in fact a state building ideal, wasn’t it? So I mean it was incorporated into this subsequent re-definition of populist identity or patriotism over the last century. I suppose it is natural that today most Americans do not identify with it, are not even aware of it. There is simply no consciousness. And some of them are probably shocked when they read the real history of their country, those who read it properly. On the other hand, the Israeli settler colonial project has not yet triumphed. It is certainly doing well. It is certainly moving forward. But has not triumphed.

EP: This is what is so interesting about the Australian and Canadian context. You could say that similar to the US, the settler colonization of Australia was completed. Settlement up North begins in middle 1860s, by the early nineteen hundreds we could say it was “complete” insofar as there was no hope of liberation.

RK: But it continues until this day?

EP: But, nevertheless, both in Canada and in Australia the identity of settler Indigenous is not unconscious. It’s in the foreground, it’s part of a constant everyday politics and a national politics that is quite distinct from the United States. I’ll give you an example of an empirical nugget around which the answer of race and capitalism and settler colonialism has to work, when it is working in the United States. The vignette is Barack Obama’s first term. He is in the White House for the first time and he’s standing before, an iconic landscape, upstate New York somewhere. And Obama turns to the picture with his arm outstretched and he says, “I am proud to be American, Americans came wave after wave and settled this beautiful, empty land.”