The last two years have seen heated debates within Europe and the United States about the costs of hosting Syrian and other refugees. However, there has been almost complete silence about another aspect of their involvement in the conflict: the extent of arms sales to the Middle East. Between 2011 and 2014, and based on conservative estimates, Europe earned twenty-one billion euros from the arms trade to the Middle East while it spent nineteen billion euros on hosting approximately one million Syrian refugees. During that same period, the United States earned at least eighteen billion euros from arms sales, while accepting about eleven thousand refugees. Aware of the consequences of weapons proliferation, European politicians may have opted for a tradeoff: making their taxpayers shoulder the short term cost of hosting refugees in exchange for profits to the arms industry.

Throughout the war in Syria, Western-made weapons have been transferred to various Syrian opposition groups fighting the Syrian regime as well as each other. Reports surfaced in 2012 that Syrian rebel groups used Swiss-made hand grenades initially sold to the United Arab Emirates (UAE). As a result, Bern decreased its arms exports to the UAE from 132 million euros in 2012 to 10 million euros the following year, yet increased it again to 14 million euros in 2014. Weapons produced in Belgium were also transported to the various warring factions in Syria.

Between 2011 and 2014, Switzerland—which prides itself in being a harbinger of peace—earned 1.5 times more from weapons sales to the region than what it spent on hosting thirteen thousand Syrian refugees. Similarly, while Belgium’s revenues from arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the UAE amounted to 1.18 billion euros, it spent 0.71 billion euros on hosting sixteen thousand Syrian refugees. For other arm producing countries, these ratios are astoundingly higher as will be shown below.

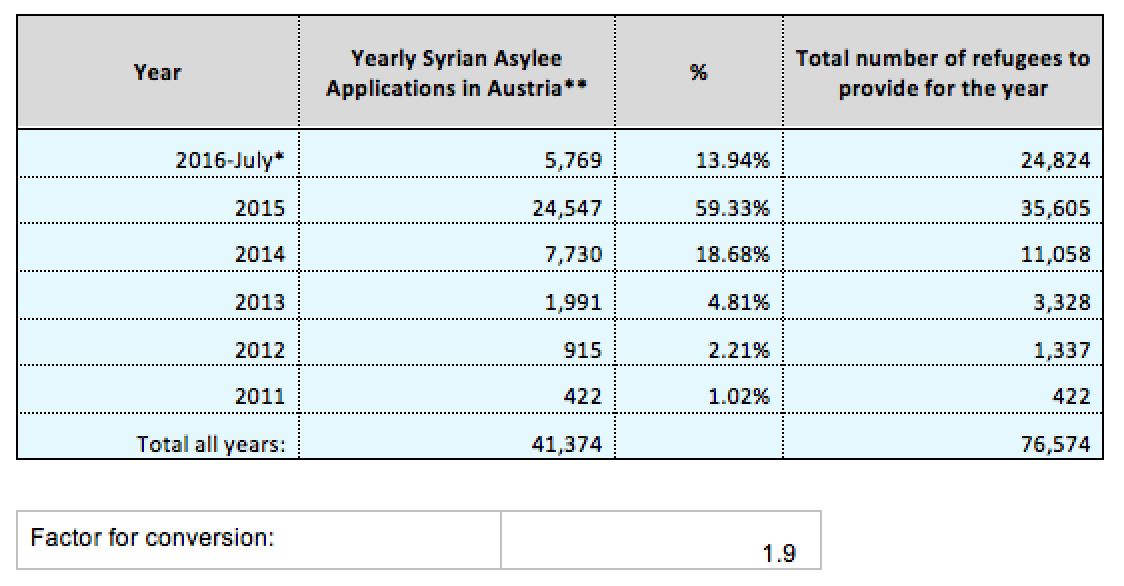

In this brief study, we aim to assess the value of official weapons sales between arms producing countries and the Middle East between 2011 and 2014. The focus will be on trade with Jordan, UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and Turkey (JUQKKT)—countries that have close links with the Syrian armed opposition. We then compare arms sales revenues with the cost of hosting Syrian refugees seeking protection in arms-exporting countries[1]—while taking note that comparing earnings from the arms trade with hosting refugees does not address or assume away the immorality of weapons sales. We grouped weapons manufacturers and transfer countries under the “Friends of Syria” banner—in reference to the group formed in 2012 by former French President Nicolas Sarkozy composed of France, the United Kingdom, the United States, Germany, Italy, Turkey, UAE, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Egypt—and the rest under Eastern Europe.[2] The focus on Western countries does not imply they are solely to blame for the weapons trade. However, reliable data on arms exports from China, Russia, and Iran are not readily available. Though we do try to provide some plausible estimates based on available data. While this prevents us from including these in our calculations, it does not affect our main premise of the indirect but foreseeable link between Western arms transfer to the Middle East and the wave of refugees.

We relied on official national reports, which record approved weapons export licenses rather than actual weapons produced and shipped to the importing country. The difference lies in that while export licenses may be approved in a given year, delivery may only occur several years down the line due to extended production cycles of military equipment. Furthermore, we note that official arms sales figures are conservative estimates knowing that at least two percent of the arms trade is unaccounted for—and is conducted through back-door deals. As we will also show, there is strong evidence indicating countries exporting to JUQKKT without it being reflected in their national records.

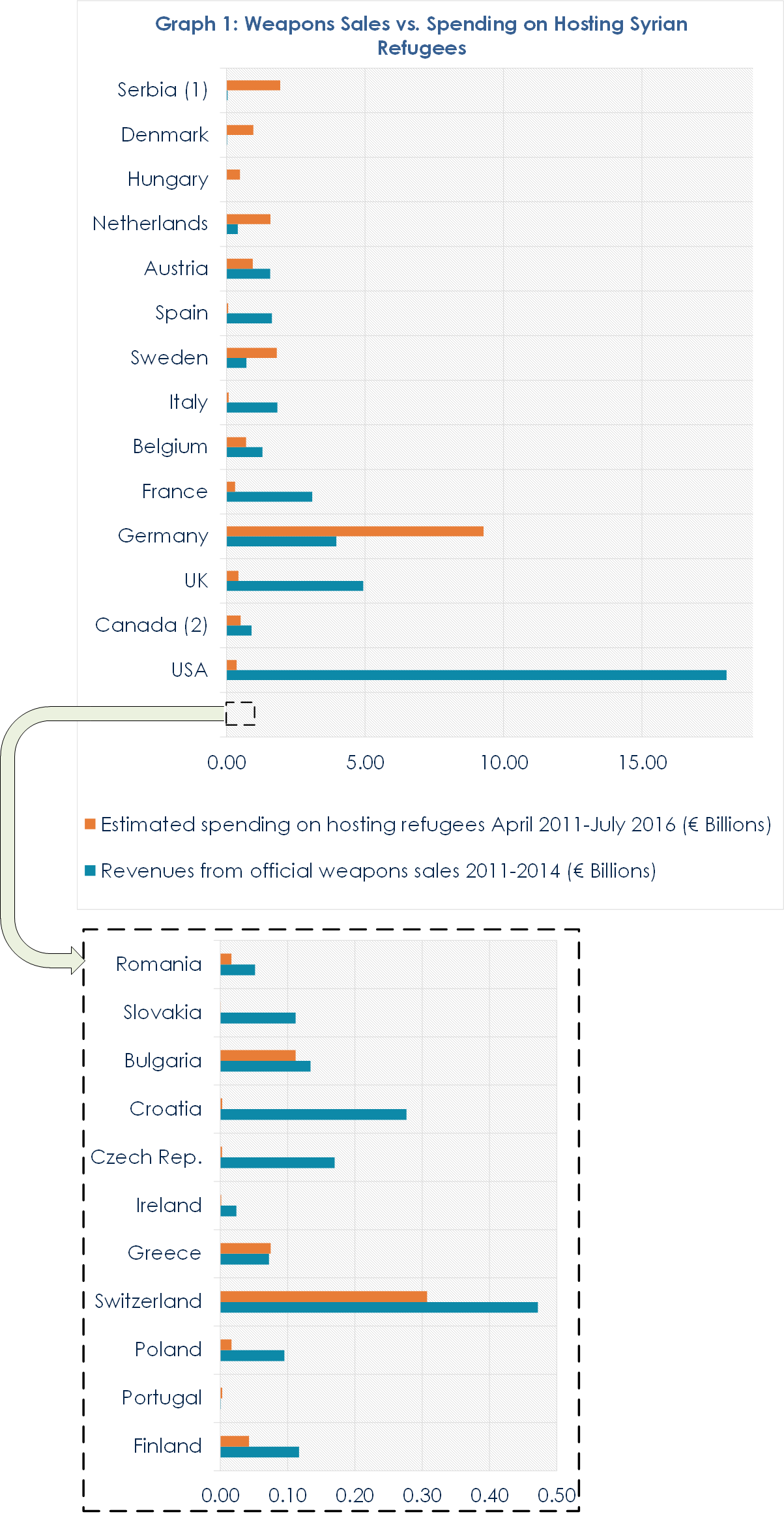

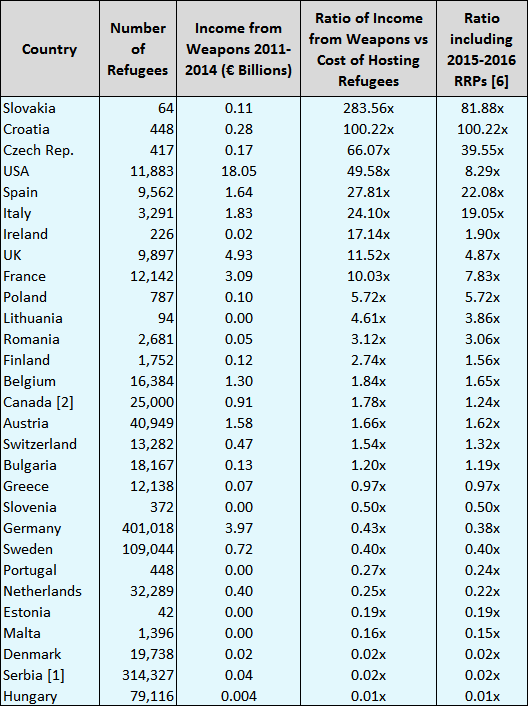

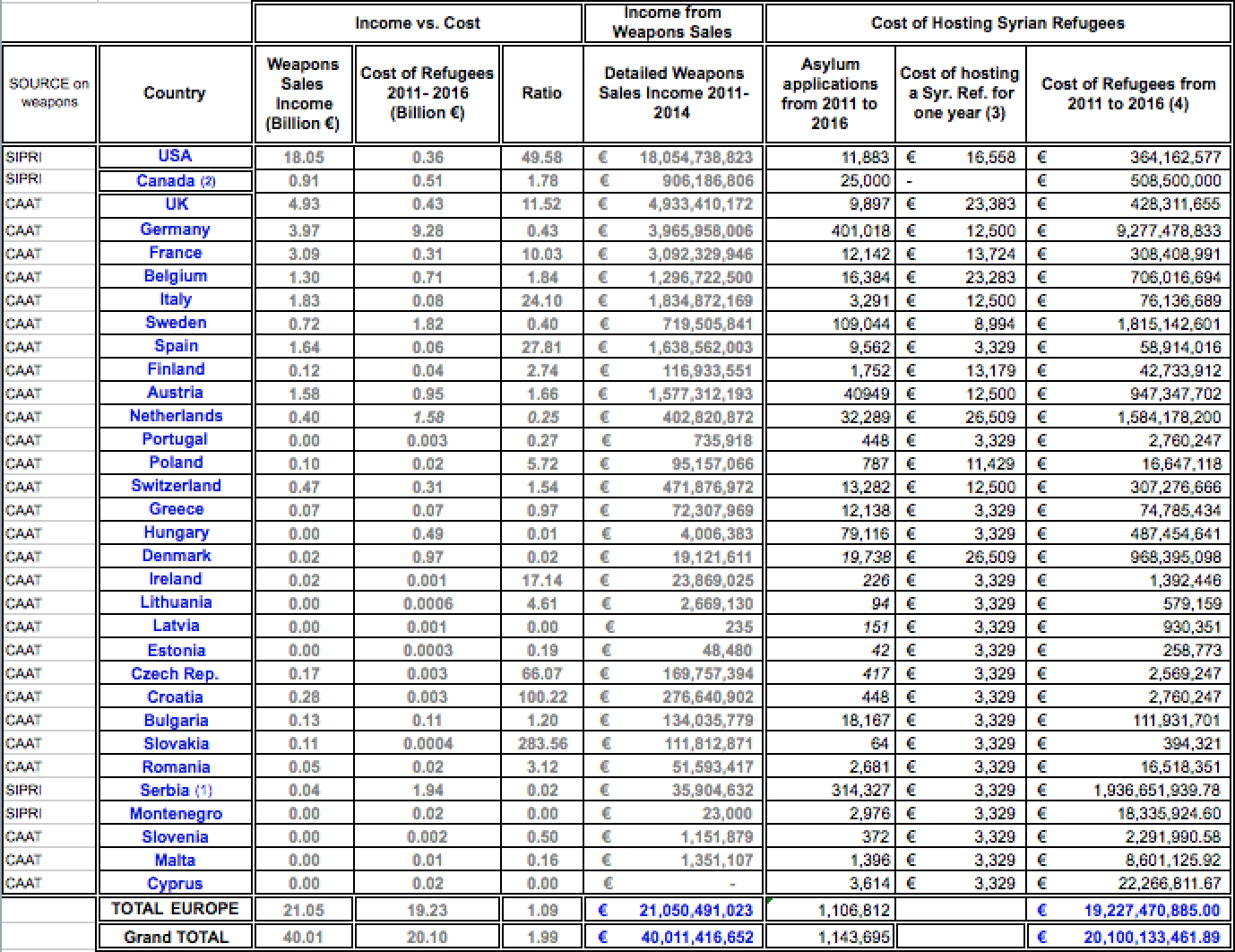

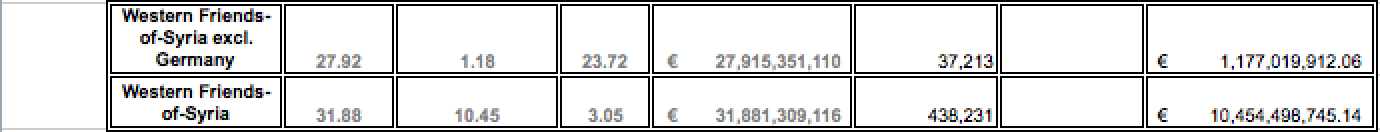

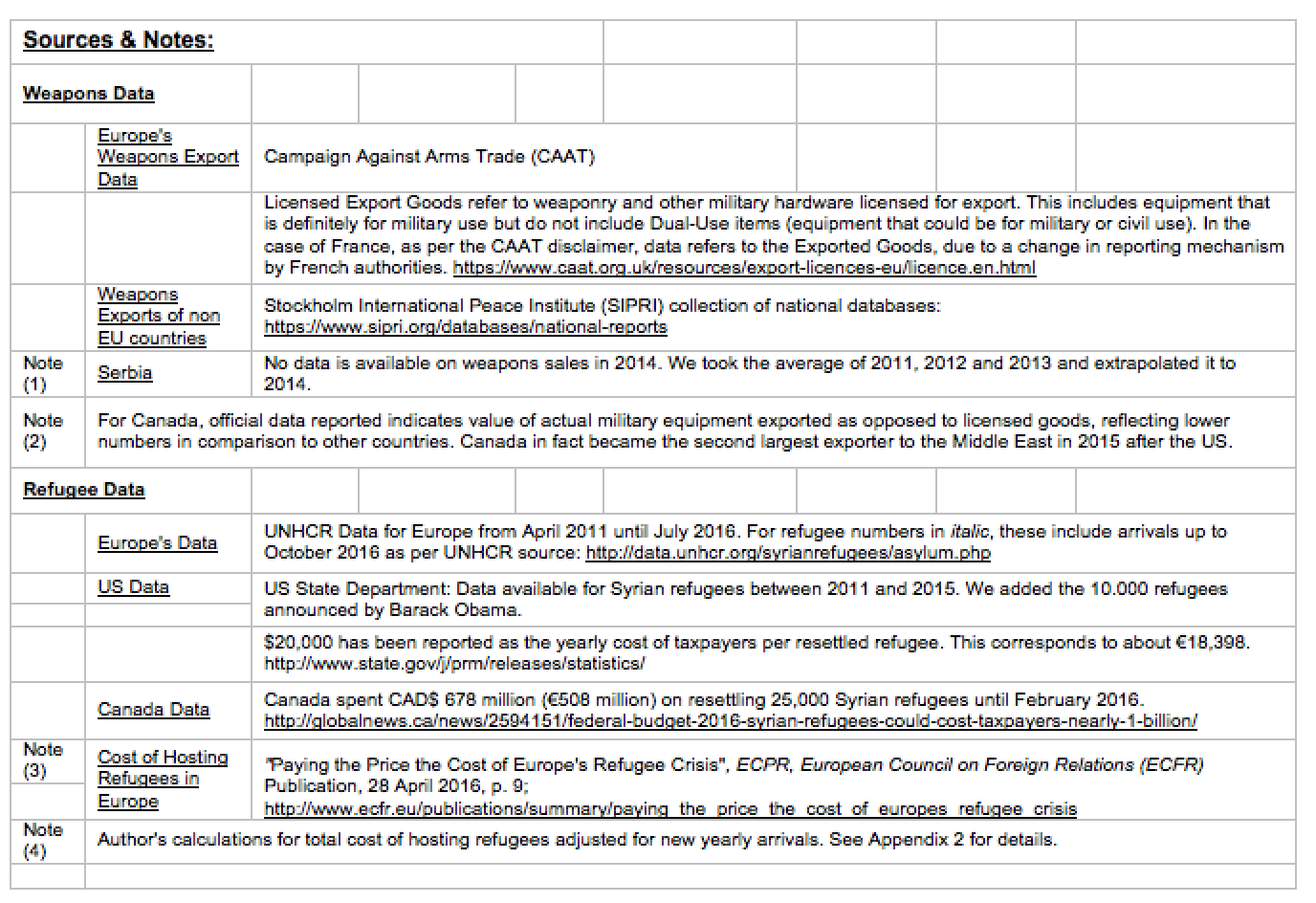

In calculating the cost of hosting refugees from April 2011,[3] we assumed that governments have continued to support refugees from the time of their asylum applications up until the end of the period under study (July 2016).[4] Also, for countries where specific data on the cost of hosting refugees is not available, we used Spain’s per capita cost as a proxy given the closer costs of living in southern Europe to the East European countries.[5] The following table, graphs, and Appendices developed by the author will form the basis of our discussion:[6]

Table 1: Country Ranking

Ranking of countries (those with more than €100 million in weapons exports or those with more than 10,000 asylum seekers) in terms of ratio of income from the arms trade versus spending on refugees.

(1) Looking at UNHRC refugee figures, Serbia has registered in an outstanding 300,000 asylum applications between 2011 and 2016. However, the Belgrade situation seems to represent a special case as it so happens that, when neighbors such as Hungary and Croatia—located along the refugees’ route to Western Europe—sealed off their borders, Serbia had little choice but to accept refugees present on its territory hoping to cross the border. In comparison, according to Interior Minister Stefanovi, “only 500 refugees requested asylum in Serbia, and 250 refugees stayed.” Yet, Amnesty International reports that the number of people apprehended crossing the Serbia-Hungary border rose by more than 2,500% between 2010 and 2015 (from 2,370 to 60,602). This has resulted in a sharp jump in the number of asylum seekers in Serbia. Faced with such numbers, the European Union announced it will provide Serbia with over €3.8 million for expanding temporary shelters and addressing waste disposal, sanitary and other needs. More recently, Serbian President Tomislav Nicolic said that Serbia is looking to host between 5,000 to 6,000 migrants (all nationalities combined), while noting that if the EU was not “angry with Hungary for the way they treated migrants, it will not be angry with Serbia either.”

(2) For Canada, official data reports the value of actual military equipment exported as opposed to licensed goods destined for export. This reflects lower numbers in comparison to other countries. Canada in fact became the second largest exporter to the Middle East in 2015 after the United States.

.png)

Based on our calculations, since 2011, Europe, the United States, and Canada spent around 20.1 billion euros to host approximately one million Syrian refugees over five years. At the same time, Western arms manufacturers are having a field day with supplying military equipment to the Middle East, a considerable number of which has ended up in the war in Syria. Europe is however at pains to consider the consequences of its gains. Comments by UNHCR’s Europe Director seem right on point: the weapons industry “kills and creates refugees.”

“Friends of Syria” or the Traditional Proponents of the Weapons Industry

The primary source of weapons to the Middle East remains by far the United States, which sees itself least concerned by the catastrophes it is helping propagate across the region. The waves of refugees fleeing conflicts seem to also be far from its radar. Leading European democracies are second to the United States in arms trade with the region (until 2014), and are quick to please the largest Middle Eastern arms purchasers. When it comes to money from the arms trade, it seems that international law and national regulations become malleable.

With the onset of the “Arab Spring,” Western governments were publicly enthusiastic about the alleged democratization of the Middle East. However, one year after the “Arab Spring,” EU- and US-licensed arms sales to the region increased by twenty-two percent and three hundred percent, respectively. Several of the Gulf regimes, troubled by the tide sweeping the region, launched a counter-revolutionary campaign. The West played right into this campaign through, among other ways, the supply of military equipment driven by ever-hawkish weapons industries. The war in Syria is no exception.

The Obama administration’s involvement in the ongoing Syrian war has been under attack by many groups as being “hands off.” Official involvement is also said to focus on direct delivery of non-lethal weapons to rebel groups. The US government however relinquishes the transfer of lethal equipment to its Arab allies, yet approves Syria as final destination. Accordingly, US-manufactured TOW missiles, previously sold to Saudi Arabia and Turkey, frequently appear in videos shot by Syrian rebels.

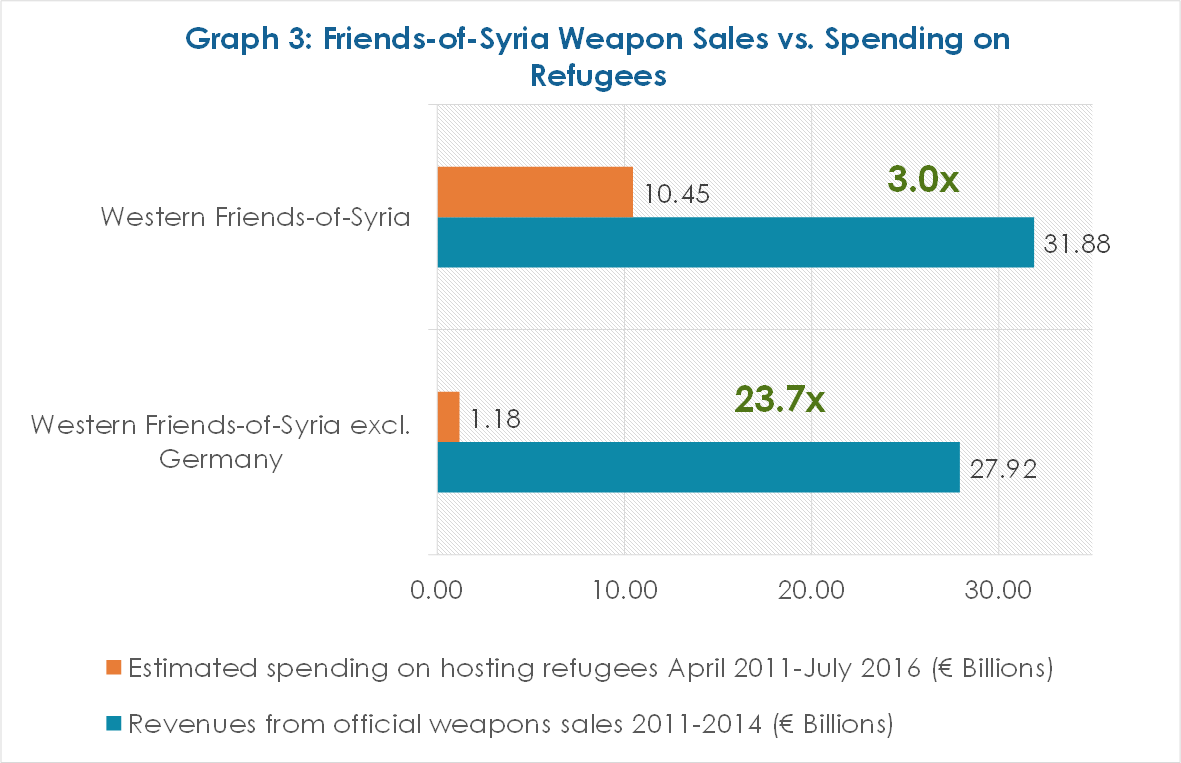

Looking at the numbers, the “Friends of Syria” earned 31.88 billion euros in weapons sales to JUQKKT and spent 10.45 billion euros on hosting Syrian refugees. Discounting Germany’s numbers, the United States, France, United Kingdom, and Italy made 27.92 billion euros in sales versus 1.18 billion euros spent on refugees (i.e., they earned twenty-three times more from weapons sales than they spent on refugees).

Western European and US officials defend weapons sales under various pretexts. For the German chancellor, the market is strategic: the Merkel Doctrine defends the export of weapons as essential instrument for peacekeeping in countries where Germany is not directly active but has vested interests. Accordingly, the chancellor calls for sustained arms deliveries in order for partners to carry out common objectives. This included a 2011 deal, unthinkable under previous governments, selling 270 modern tanks to Saudi Arabia, with tacit Israeli approval. Furthermore, while commentators may worry that were Germany to refrain from exporting weapons, others counties will, journalist German Jürgen Grässlin argues the opposite is in fact true: when the Dutch parliament refused to export used Leopard tanks to Indonesia, Germany jumped in and approved the same deal. In the meantime, German opposition groups have called for a blanket ban on arms sales to Saudi Arabia over its human rights violations. This drove the chancellor and Economy Minister Sigmar Gabriel to “critically review” arms sales to Riyadh and decide in 2015 to focus exports to Saudi Arabia on “defensive” military gear, including all-terrain armored vehicles, aerial refueling systems, combat jet parts, patrol boats, and drones. Still, German exports to Saudi Arabia increased from 179 million euros to 484 million euros in the first half of 2016. While Germany has been applauded for taking in the majority of Europe’s Syrian refugees (about 400,000), this does not exonerate it from profiting from conflicts in the Middle East prolonged by arms imports. Discounting this reality would be akin to selling heroin nearby schools, yet boasting about admitting a few children to rehab and paying for it.

Other arguments for military exports advance threats to the domestic labor market in case of implementing restrictions on the weapons industry. As such, not only industry-affiliated think-tanks but also mainstream media explicitly endorse the sale of weapons: long-time CNN news anchor, Wolf Blitzer was astonishingly worried by the possibility of halting sales to Saudi Arabia. In his view, the consequent risk of job losses across US defense contractors by far outweighs the moral argument of supporting Saudi war crimes in Yemen. Beyond the moral aspect, Wolf Blitzer overrates the industry’s job creation potential. In many countries in fact, the arms industry is a dying sector in need of government subsidies: in Germany, the industry employs 100,000 people while the renewable energy sector, where skills could be easily transferred, is currently creating 300,000 jobs yearly. In the case of the United States, allocating national spending to the clean energy, health, or education sectors would create between 50 to 140 percent more jobs than spending it on the military.

Other officials counter-intuitively advocate for Western weapons sales based on humanitarian grounds. UK Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson said that were the United Kingdom to stop supplying Saudi Arabia, “other Western countries […] would happily supply arms with nothing like the same compunctions or criteria or respect for humanitarian law [as the UK]”. UK ministers have also “sensationally claimed that Saudi Arabia is best-placed to investigate its own alleged atrocities.” Moreover, former UK Business Secretary Vince Cable recently said he was mislead by the Ministry of Defense in signing off on the sale of laser-guided Paveway IV missiles to be used in Saudi Arabia’s bombing of Yemen. Cable initially blocked the export license due to concerns for civilian deaths, yet was promised “oversight of potential targets” which the ministry now denies.

Lastly, for some European politicians, the case for weapons exports is made on a purely monetary basis. Former UK Prime Minister David Cameron boasted of his efforts to help sell “brilliant things” such as Eurofighter Typhoons to Saudi Arabia, on the same day the European Parliament voted for an arms embargo on Saudi Arabia over its bombardment of Yemen. His successor, Theresa May carried over the tradition in defense of weapons exports and said that London’s close relationship with Riyadh played a vital role in the fight against terrorism and that the Saudi regime’s co-operation was “helping keep people on the streets of Britain safe.” Comically, politicians who are the most candid about using the threat of refugees as a scaremongering tactic are also the most ardent defenders of the weapons industry: UKIP’s Nigel Farage comes to mind.

In the case of France, ties with Saudi Arabia seem to be at an all-time high with President Hollande awarding Crown Prince Mohammed bin Nayef the Légion d’Honneur for Riyadh’s efforts “fighting terrorism and extremism.” With over three billion euros in sales to Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, Jordan, and Turkey, France[7] has spent ten times less (0.31 billion euros) on hosting about twelve thousand Syrian refugees. For Italy, Prime Minister Matteo Renzi propones exempting defense equipment manufacturers from paying VAT and allowing the industry to apply for EU research grants. Italy made an astounding twetny-four times more in arms sales compared to its spending on 3,300 Syrian refugees.

The majority of Western leaders in countries with powerful defense industries are proud defenders of their weapons manufacturing companies. They seem however either conveniently or naively oblivious to any correlation of arms exports and refugees and are yet in awe when faced with unprecedented waves of refugees at their borders. We ask: what else can they expect?

The New Kids on the Block or the Revival of East Europe’s Weapons Industry

East European countries have opened the doors to stocks from the former Yugoslavia and are reviving their domestic arms industries through the recent boost in arms trade to the Middle East. However, they seem to show the greatest levels of racism towards refugees fleeing conflicts.

A July 2016 investigation published by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project indicates that eight East Europeans countries (Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Montenegro, Slovakia, Serbia, and Romania) have since 2012 approved weapons and ammunition exports in value of just under 1.2 billion euros to Saudi Arabia (€806 million), Jordan (€155 million), UAE (€135 million), and Turkey (€87 million). The investigation indicates that these countries’ exports are distributed by Saudi Arabia to its regional allies, Jordan and Turkey, who steer two command hubs transferring the weapons by road or through airdrops into Syria. Gradually in fact, ex-Yugoslav-made weapons appeared in the hands of a plethora of armed groups around Syria’s battlefields. This has been documented by Eliot Higgins, writing under the name of Brown Moses, who mapped the weapons’ spread throughout the conflict.

Accordingly, Belgrade, Zagreb, Bratislava, and Sofia have become main export hubs to the Middle East. Specifically, in 2015 Serbia agreed to 135 million euros of arms export licenses to Saudi Arabia. It had rejected similar requests in 2013 for fear weapons would be diverted to Syria. At a press conference in August 2016 following the BIRN investigation, Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic said that, while he was defense minister in 2013, he “probably received” intelligence that arms could end up in Syria. “Do not ask me what has changed. In 2015, I was not defense minister and I can’t know [what happened]. I will take a look,” he said. Based on Serbia’s national reports, the export licenses to Saudi Arabia rejected in 2013 were worth twenty-two million dollars.[8] Also in 2013, the Serbian government denied four arms and military equipment import applications from the United Kingdom, Bulgaria, Belarus, and the Czech Republic. These import worth 9.9 million dollars were intended for re-sales (in the form of exports) to Saudi Arabia.[9] Vucic was candid about the benefit of the arms trade and said at the 2016 press conference: “I adore it when we export arms because it is a pure influx of foreign currency.”

In Bratislava, public broadcaster Slovak Radio and Television reported that in 2015 “Slovakia exported to Saudi Arabia 40,000 assault rifles, more than 1,000 mortars, 14 rocket launchers, almost 500 heavy machine guns and more than 1,500 RPGs.” The Prime Minister defended the arms deal noting “if we don’t sell [arms], somebody else will, but don’t come crying to me if a lack of arms deals causes the loss of jobs for our people.” Slovakia welcomed a whopping 64 Syrian refugees costing Bratislava 400,000 euros. Slovakia can be crowned for a monumental 284 ratio of weapons sales to cost of refugees.

For Croatia, data indicates that in 2013 and 2014 Zagreb sold over 155 million euros in ammunition and small arms among others to Saudi Arabia. Moreover, thirty-six round-trip flights were conducted between Amman and Croatia from December 2012 through February 2013: Jordanian cargo aircrafts airlifted a large Saudi purchase of infantry arms from a Croatian-controlled stockpile from Zagreb to Amman. In December 2012 alone, exports to Jordan amounted to over 6.5 million US dollars; these shipments do not follow regular business patterns and Croatia`s previous arms exports to that country consisted of fifteen pistols worth 1053 US dollars sold in 2001. Croatia’s official national reports in fact indicate 115 million euros in exports to Jordan between 2013 and 2014 and no exports in 2012. We can thus safely assume the existence of under-the-table deals, which go unreported.

Along the same lines and as an additional point of interest regarding the indirect forces at play in the Syrian theater is that a consortium of Serbian-owned CPR Impex, one of the region’s most important arms brokers[10], and Israel’s ATL Atlantic Technology bought Montenegro Defence Industry in February 2015. Since August 2015, MDI arranged export deals of 250 tons of ammunition and 10,000 anti-tank systems to Saudi Arabia in value of over 2.7 million euros. We note that prior to 2015 and since 2006 (based on the availability of reports), Montenegro had not conducted any significant arms trade with the Middle East except for Israel, where the end user country was stated to be Afghanistan, Iraq, or United States, and with Yemen in 2010.

As for Bulgaria, the largest state-run arms producer, VMZ-Sopot has also hit the jackpot: after being insolvent in 2008, the plant has been working at full capacity since 2015. It paid off around eleven million euros in debt and has created 1,200 new jobs. Furthermore, sales growth went from around ninteen million euros in the first half of 2015 to around eighty-six million euros in the first half of 2016. VMZ Sopot’s net profit surged to around 600,000 euros from a net loss of thirty-five million euros in the same period. While Bulgaria took in 18,000 Syrian refugees, a 2015 report by the German Pro Asyl foundation entitled “Humiliated, ill-treated and without protection” provides shocking accounts from asylum seekers in Bulgaria. Refugees are subject to inhumane and degrading treatment by police and prison guards including extortion, abuse as well as torture.

In the case of Russia, a major weapons supplier to the Syrian regime—despite limited availability of data—we know that at least ten percent of its arms exports went to Syria. “Russia reportedly has $1.5 billion worth of ongoing arms contracts with Syria for various missile systems and upgrades to tanks and aircraft, reportedly doubling that investment in small arms sales since the beginning of the Syrian civil war.” Furthermore, military training provided by Russia since the beginning of the conflict ought to also be quantified. Despite the very direct role Russia has played in the Syrian war, the country has currently only accepted 1,395 Syrian refugees on temporary asylum and has even deported one Syrian refugee.

Through indirect transfer of considerable weapons quantities to rebel factions, East European countries have acquired an unexpected but important role in the war in Syria. Nevertheless, they are quick to encourage and push refugees towards continental Europe while taking in a ludicrous handful of asylum seekers.

A Dishonest Debate—For the Most Part

Weapons industries are by and large applauded for turning the wheels of the economy at home. Little scrutiny is however carried out over the havoc it is creating elsewhere in the world. This time around, with unprecedented quantities of weapons sold to the Middle East and those transferred to Syria, reality is hitting closer to home. A different debate ought to take place.

In a different spirit, countries such as Portugal consider the refugee influx as an opportunity to revive some regions of the country. Lisbon is in fact offering to welcome up to 5,800 more refugees in addition to the 4,500 it already agreed to take as part of the European Union’s refugee quota system. Portugal has “only” sold 500,000 euros worth of weapons to the Middle East.

According to the former economic adviser to the president of the European Commission, Philippe Legrain, refugees are in fact unlikely to decrease wages or raise unemployment for native workers. Most significantly, calculations indicate that while the absorption of so many refugees will increase public debt for the European Union by almost sixty-nine billion euros between 2015 and 2020, during the same period refugees will help GDP grow by 126.6 billion euros. In fact, a one-euro investment in welcoming refugees can yield nearly two euros in economic benefits within five years. Legrain also highlights how refugees could solve an impending demographic challenge in Europe.

The debate over the flows of refugees and the heavy burden on societies is thus flawed. Not only is blaming refugees for fleeing war and seeking stability unjust, it disregards Western countries’ complicity in cashing in on the wars they are escaping. Even more so, the question remains as to the distribution of profits from the global arms trade between national governments brokering the deals and arms manufacturers—knowing that it is the former who covers the cost of resettling refugees. Rather than at refugees, anger and protest should thus be directed at the weapons industries and the revolving doors linking them to policy makers. The latter ought to face more opposition to the war-profiting policies they espouse.

While we focused our discussion on the case of Syrian refugees and the weapons feeding the war in Syria, other conflicts in the Middle East deserve as much scrutiny. Arms sales by the US, Canada, Germany, UK and France feeding conflicts in Iraq, Yemen and Libya should also be taken into account in calculating the debt the West has towards the Iraqi, Libyan and Yemeni people. The only reason keeping Yemenis from joining Syrian refugees in Europe and beyond is the reality that their country is landlocked by Saudi Arabia on the one hand and by a naval blockade on the other. Over three million Yemenis are currently internally displaced and fourtheen million are food insecure.

Appendix 1: Master Data & Calculations

Appendix 2: Notes on Calculations

1. Factor used to convert the cost of one refugee per year into cost over the period Jan 2011 to July 2016 according to arrival pattern

Here we assume that in every year, all the accumulated number of asylees that arrived since 2011 were supported.

*Corrected 2016 estimate for less than a full year using factor: 0.6

**Detailed numbers of yearly refugee arrivals was only available through national Austrian statistics, hence the slight discrepancy (of 425) between total Syrian asylee applications in Austria in this table and the ones reported for the year by UNHCR in Appendix 1.

Source: http://www.bmi.gv.at/cms/BMI_Asylwesen/statistik/start.aspx

[1] Our analysis relies on research of open-source data and includes articles, official EU and OECD data and analysis as well as research by think tanks and NGOs dedicated to the study of the arms trade. We welcome any further information by readers, which may not be available openly to the pubic.

[2] Egypt is, based on our findings, the exception in the group and has not participated in the sale or transfer of weapons to Syria.

[3] Start of UNHCR data availability on Syrian asylum seekers in Europe.

[4] Please refer to Appendix 2 for detailed calculation.

[5] Spain’s cost of 3329 euros for hosting one refugee for one year was thus applied to Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Greece, Malta, Montenegro, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Spain has the lowest cost per refugee among the countries selected (albeit it is a cost estimate for 2009) and has a higher per capita GDP (thirty thousand euros) than that of the East European countries (approximately eight thousand euros). It is thus highly likely that cost per refugee there is even lower than that of Spain.

[6] RRPs refers to the yearly UN Regional Response Plan, which is an inter-agency plan to cover the needs of refugees fleeing Syria and people in host communities in Syria`s neighbors (Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq and Egypt) who took in over 4.8 million refugees. Reliable and consistent data is limited on actual RRPs disbursements (versus pledges) for all donor countries under study and for the entire 2011-2016 period. For reference, we included actual disbursements available on OCHA`s Financial Tracking Service for the RRPs of 2015-2016. This limitation in data does not impact our analysis as our calculations aim to address the question of hosting refugees in arms exporting countries as opposed to those in Syria`s neighbors. While taxpayer money is the source of both (support of refugees at home and in countries around Syria), the question of supporting Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Iraq and Egypt in hosting Syrian refugees is not an issue of debate. In this sense, the article rather aims to contribute to the Western debate on the wave of refugees at home.

[7] We note that a French government source indicate that in 2014 alone, France made €3.6 billion in weapons deals with Saudi Arabia, while the number provided by CAAT is far less. Although more conservative, for purposes of comparability and data manipulation, we will focus on statistics provided by CAAT for EU countries.

[8] “2013 Report On Performed Activities of Exports and Imports of Arms, Military Equipment, Dual Use Goods, Arms Brokering and Technical Assistance”, Serbian Ministry of Trade, Tourism and Telecommunications, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Annex 10, p. 76

[9] Ibid, Section 11, p.27 and Annex 11, p.77

[10] CPR Impex’s owner, Crnogorac was arrested in July 2014 by Serbian police on charges of abuse of office over a series of military tenders for surplus military equipment his company participated in between 2011 and 2013. The charges were subsequently dropped, but he has since been investigated by the UN for allegedly violating arms sanctions by trading with Libya. http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/montenegro-opens-weapons-supply-line-to-saudi-arabia-08-02-2016