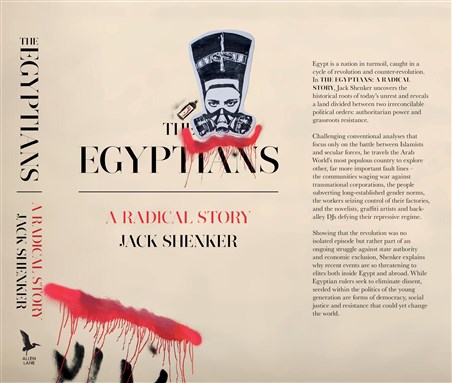

[This is an edited extract from Jack Shenker’s book, published in the UK as The Egyptians: A Radical Story (Allen Lane / Penguin) and in the US as The Egyptians: A Radical History of Egypt’s Unfinished Revolution (New Press) – for more details, see here.]

In late February 2016, President Sisi strode up to the podium at Cairo’s El Galaa theatre, looked into the waiting television cameras, and addressed the nation. “Don`t listen to anyone but me,” he declared. “I am dead serious. Be careful, no one should abuse my patience and good manners to bring down the state. I swear by god that anyone who comes near it, I will remove him from the face of the Earth. I am telling you this as the whole of Egypt is listening. What do you think you`re doing? Who are you?”[i]

As his voice grew louder, and his tone more furious, an official banner which had been hung behind Sisi on the stage came into view. ‘2016, Year of Youth’, it read.

The previous month, Sisi’s government had mounted the biggest security crackdown in the country’s modern history: an attempt to thwart any anti-regime protests on January 25th, fifth anniversary of the start of revolution. A few weeks after his speech, riot police were forced to flood the streets once again as thousands defied the law and demonstrated against the ceding to Saudi Arabia – Sisi’s strongest international ally – of two Red Sea islands that the Egyptian state had previously claimed as its own.

The event at El Galaa, complete with the top-down designation of 2016 as a celebration of the country’s young people – record numbers of whom were now behind bars – was intended to remind Egyptians of who it was that had the power to speak in post-Mubarak Egypt, and of the heavily-militarised lines which demarcated the limits of mass political participation. It was designed to place Sisi, and the state he presided over, beyond the scope of dissent. It failed. At one point during the address, Sisi attempted to demonstrate his loyalty to Egypt by offering to “sell himself” if it would benefit the nation. Within minutes, pranksters had listed one ‘slightly used president (previous owners: Gulf monarchs)’ on eBay; bidding reached $100,000 before the auction was shut down.[ii] When I visited the relevant webpage, an automated message warned me that ‘this product may not ship to the United Kingdom’. As Mubarak, Tantawi and Morsi discovered to their cost, the more bombastic Egypt’s elites become, the more that many Egyptians tend to snigger.

I completed the epilogue of my book, ‘The Egyptians’, in late 2015; in the year that has followed, the central faultline of Egypt’s current, extraordinary historical moment – a struggle over whether politics is to remain the preserve of elites or whether its walls can be overtopped by the past half-decade’s colossal tide of popular sovereignty from below – has become more pronounced. In the space between the breaking of an old world and the formation of a new one, stewards of the former have unleashed more violence, and silenced more voices, than any Egyptian ruler in living memory. “I haven`t seen a worse situation than what we have now: the violations, the impunity, the defiance by police,” says Aida Seif el-Dawla, a psychiatrist and co-founder of the el-Nadim centre, which attempts to rehabilitate victims of state torture.[iii] In 2015, el-Nadim documented almost 500 deaths as a result of police brutality and more than 600 cases of torture in detention[iv]; soon after the figures were published, the state moved to shut the centre down.[v] Other prominent human rights organisations have seen their offices raided and their assets frozen, while the activists who staff them are banned from travel or sentenced to prison.[vi]

The impunity referred to by el-Dawla is asserted partly through the ad hoc actions of Egypt’s security forces – the street vendor machine-gunned by a policeman after an argument over the price of a cup of tea, the veterinarian pummelled to death by officers in a cell, the middle-aged man dragged from a coffee shop to have his spinal cord cut[vii] – but also through the establishment of new norms, as chilling as they are increasingly banal. One such practice is forced disappearances, an ongoing epidemic of which echoes the worst of Latin American dictatorships in the 1970s. In the first half of 2016, 630 Egyptians ‘vanished’ at the hands of police or intelligence agencies; in the same period, there were more than seven hundred extrajudicial killings.[viii] Lives are being lost under Sisi’s regime, but so too is time – the thousands upon thousands of cumulative days expended by detainees in dark, dank rooms that will never appear in the official records, the endless empty hours spent by relatives waiting, wondering, or mourning.

This sense of official impunity is reinforced by rhetorical absurdity on the part of the state, which repaints reality to show that it can. After a taxi driver was shot dead by an officer in Cairo’s Darb el-Ahmar district following a dispute over the fare, one government statement declared: “The bullet mistakenly came out of the gun”.[ix] There are no enforced disappearances, according to the interior ministry; police violations are not systematised but rather the result of isolated ‘individual acts’. Satirists have seized upon such language, and the ‘Ministry of Individual Acts’ is now a common trope. One recent cartoon, in al-Masry al-Youm, depicts a policeman sweeping countless corpses into a bag while simultaneously reassuring a reporter that “these are all individual acts”.

But of course these days the satirists themselves must tread carefully. Like authors, publishing houses, galleries, theatres, musicians, poets, journalists and TV hosts, they too have been targeted by a war on cultural freedoms.[x] Five members of comedy troupe Awlad al-Shawarea (‘Street Children’) were arrested in May 2016 on suspicion of ‘insulting state institutions’, while popular cartoonist Islam al-Gawish found himself detained for ‘managing a Facebook page without a license’.[xi] In February 2016, the novelist and Sisi critic Ahmed Naji was handed a two-year jail sentence for ‘violating public modesty’; at his trial, the court heard that one of Naji’s works caused a reader to suffer heart palpitations and a drop in blood pressure owing to its sexual content.[xii] Naji was released from jail in December, but at the time of writing his legal status remains uncertain. My own book has not been immune to the rising wave of censorship; in early 2016 it was seized by the Ministry of Culture and effectively banned from sale in Egypt, a decision that was only reversed several months later after considerable international pressure.[xiii]

The Italian political theorist and revolutionary Antonio Gramsci once warned that, within any interregnum between old and new, a wide variety of morbid symptoms will appear. In Egypt’s case, the morbidity has been great indeed.

And yet, even as it lashes out with unprecedented savagery, the contradictions of Sisi’s leadership – teetering atop a model of power that has been irreparably shattered by the revolution, and justified by a promise of stability and coherence rendered impossible by virtue of the leadership’s very existence – are mounting. “An authoritarian regime may be unpopular, even loathed, but at least it has rules,” observed Josh Stacher, a political science professor who specialises in Egypt, in early 2016. “The rules may bear little resemblance to the law, but relations between state officials and society come to have a predictable rhythm. People understand where the red lines are, and they can choose to stay within them or to step across.”

“Egypt does not work this way under the field marshal who became president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi,” Stacher continued. “If Sisi survives to fashion a regime as falsely stable as what reigned in the bad old days of Mubarak, he will be a magician. At present, he resembles a quasi-comical warm-up act, albeit one with an army, while everyone awaits the next chapter of Egypt’s tumultuous story.”[xiv]

In its desperate, ceaseless attempt to conjure fresh demons so as to underscore the need for a strongman, while at the same time delivering the calm and predictability craved by co-opted elites, the counter-revolution has been forced to walk a near-impossible tightrope, and every inevitable stumble tugs at the fraying threads a little further. The Red Sea islands imbroglio has dented Sisi’s hyper-nationalist credentials even among his own supporters; lurid cautions against the ever-present threat of foreign hands seeking to destabilise the nation sound less convincing when it is common knowledge that Gulf aid is needed to keep the lights on and the government has accepted a $12 billion loan bailout from the IMF.[xv] A whole new round of austerity measures, implemented against the backdrop of intense currency, budget and current account crises, are trailed alongside images of Sisi driving down a four kilometre long red carpet, revelations of multimillion dollar corruption rackets and cabinet ministers lodging on the public purse for months after month in five-star hotels.[xvi]

Amid the gaping discrepancy between regime words and actions, it is little wonder that despite the staggering costs, Egyptians are still opting to air their grievances by rallying in public. Over the past twelve months transport workers in Alexandria, lawyers in Damietta and taxi drivers in Cairo have joined state telecoms employees, shipyard factory workers, ceramics plant employees and doctors in holding strikes; in Beheira, drought-stricken villagers have refused to pay their water bills; in Luxor, Ismailia and the capital, huge protests have erupted following incidences of police torture; following a security raid on the national press syndicate, reporters held a large demonstration and began deliberately distorting the interior minister’s photo and refusing to print his name.[xvii] In the columns of pro-state media outlets, notes of establishment disquiet can increasingly be heard – not just over the division of the spoils in Sisi’s Egypt, but because of his failure to tranquilise unrest. Such are the intractable dilemmas of a government that is currently considering the possibility of offering Egyptian citizenship to foreign financiers as an incentive to invest, while existing citizens are ‘disappeared’ by the security services at the rate of nearly five a day.[xviii]

Throughout it all, Sisi’s western sponsors have continued to cleave to him: a familiar face in an ever-more unfamiliar region, surrounded by a world that – shaken by rising anger against economic and political exclusion, and a crumbling of traditional authority – grows less recognisable by the day. In the twilight months of the Obama administration John Kerry remained a regular visitor to Cairo’s presidential palace, where journalists are banned from the ritual photoshoots, and the relationship between Sisi and incoming US president Donald Trump appears to be one of mutual admiration.[xix] Sisi has signed huge new arms deals with both the US and France, and in late 2015 then British prime minister David Cameron rolled out his own red carpet for Egypt’s autocrat at Downing Street.[xx] His successor, Theresa May, has promised ‘a new chapter in bilateral relations’ between the UK and Egypt, and avoided any public mention of human rights.[xxi]

This is despite the fact that, in early 2016, the corpse of young Giulio Regeni, an Italian PhD candidate studying at the University of Cambridge, was found abandoned on the roadside in the outskirts of Cairo, his neck broken and his body subjected to ‘animal-like’ violence that experts believe is highly consistent with torture by the Egyptian security services.[xxii] In response to a global outcry, Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi – the man who saluted Sisi in Sharm el-Sheikh with the proclamation that ‘your war is our war, and your stability is our stability’ – was forced to temporarily withdraw his country’s ambassador to Cairo. The close partnership between Egypt and Italian energy giant Eni has been largely unaffected by the fallout.[xxiii]

At vigils for Regeni, Egyptians held up signs reading ‘Giulio was one of us, and was killed like one of us’. “Italian officials want their gas deals and their anti-terror coalition, and they have always known what the price is,” wrote Cairo-based journalist Isabel Esterman in Mada Masr. “They just expected that somebody else – somebody else’s children – would be the ones to pay for it.”[xxiv]

Regeni’s murder, and the architecture of state terror from which it emerged, has helped illuminate the west’s own uneasy tightrope walk over the Nile and exposed points of vulnerability in the relationship between Sisi and his international backers. Just as importantly, it has underlined how profoundly unstable Egypt’s status quo is, and the extent to which the underlying dynamics of Egyptian authoritarianism have been churned into crisis by successive years of revolt. Mubarak would not have allowed a white European to be tortured to death in such a prominent manner, inviting needless controversy; in the wilds of today’s Egypt, Sisi lacks both the choice and control to follow suit. The counter-revolution’s arsenal of defences is more ferocious, and more fragmented, than that held by the state before 2011, precisely because the landscape beneath its feet has been so thoroughly rearranged by revolution.

Earlier this year, historian Khaled Fahmy noted, “We, the people… have pried open the black box of politics. Politics is no longer what government officials, security agents or army officers decide among themselves. It is also no longer what university students demonstrate about, what workers in their factories struggle about or young men in mosques whisper about. Politics is now the stuff of coffee shop gossip, of housewives’ chats, of metro conversations, even of pillow talk. People now see the political in the daily and the quotidian. The genie is out of the bottle and no amount of repression can force it back in.”[xxv] The point is that it is not just Egyptian citizens who have been transformed by January 25th and its aftermath, but the individuals and institutions they are up against; hence why the state is mired in fear, and drawn to such intense and often self-defeating acts of repression. The revolution’s first wave of political gains has certainly been obliterated, and yet, as Egyptian blogger Baheyya points out, “in the traumatized memories of a grasping ruling class, it remains evergreen.”[xxvi]

My book begins with a description of young children playing games of revolution in the school playground; several years later, those same children are now in their mid to late teens. Every summer, all students in Egypt who have reached the final year of secondary school must take a series of compulsory exams which determine not only what university course they will end up on, but essentially their entire professional path in the future. The tests are exceptionally stressful, and in 2016 they were made even more so by the leaking of test papers online, which compromised their integrity and caused many exams to be cancelled or postponed at the last minute. For many kids who have spent their formative years in the flux between Mubarak and Revolution Country – tapping into a new, thrilling language of agency and change while watching their family’s living standards decline, their friends being arrested and their coffee shops raided, looking ahead to an economy in which almost half of young people are unemployed[xxvii] – this disruption to the exam schedule was the final straw.

And so they did what they know how to do best: what they had practised for so long in so many playgrounds, including that of Zawyet el-Dahshour. Hundreds of schoolchildren took to the streets in Cairo, and fought running battles – this time for real – with police in armoured vehicles, who fired rubber bullets in an attempt to disperse them. Protests quickly spread to Alexandria, Assyut, Port Said and beyond. It was Ramadan, which meant that many of the students were fasting from all food and liquids while temperatures were nearing 40 degrees centigrade, but it didn’t matter: they sprayed water over each other’s faces to cool themselves down, and shared around onions and sodato help counteract the tear gas. Despite all the coercive laws, all the brutal crackdowns, and all the violence ranged against them, these children openly contested the power of those who sought to limit and determine the shape of their lives, because that is their norm and it is not going away.

“We don’t care [what the police do],” said one 18 year old named Mostafa. “There can be no hesitation – this is our future. If they get rid of us today, we’ll come back tomorrow, and the day after, and the day after. We will keep escalating until something happens.”[xxviii]

[ii] Brian Ries, ‘For sale on eBay: One slightly used Egyptian president’, Mashable (24 February 2016)

[iii] Brian Rohan, ‘Egypt threatens to shut down center documenting torture’, Associated Press (6 April 2016)

[vii] ‘Update: Prosecution orders 4-day detention of policeman accused of killing tea seller’, Mada Masr (20 April 2016) / ‘Police officer sentenced to 8 years in prison over death of Ismailia vet’, Mada Masr (10 February 2016) / ‘Autopsy confirms Talaat Shabeeb tortured to death in Luxor jail, 4 officers detained’, Mada Masr (4 December 2015)

[viii] ‘Egypt: Hundreds disappeared and tortured amid wave of brutal repression’, Amnesty International (13 July 2016) / Brian Rohan, ‘Egypt rights group says 754 extrajudicial killings in 2016’, Associated Press (8 June 2016)

[x] For references and more information on each of these examples, see hyperlinks at Jack Shenker, ‘Statement on book ban in Egypt’, Medium (26 July 2016)

[xi] ‘Egyptian satirists arrested for mocking president’, Guardian (10 May 2016) / Walaa Hussein, ‘Egyptian cartoonist arrested for `unauthorized` Facebook page’, Al-Monitor (5 February 2016)

[xvi] ‘The Ruining of Egypt’, Economist (4 August 2016) / ‘Pile of trouble: gigantic red carpet stirs up Egyptian media storm’, Guardian (8 February 2016) / Eric Knecht and Maha El Dahan, ‘Egypt`s wheat corruption scandal takes down embattled supply minister’, Reuters (25 August 2016) / Gamal Essam El-Din, ‘Egypt MPs seek to withdraw confidence from minister of supply’, Ahram Online (20 August 2016)

[xvii] Robert Mackey, ‘Egypt’s Newspapers in Open Revolt Over Police Attack on Press Freedom’, The Intercept (5 May 2016)

[xviii] Safiaa Mounir, ‘Will investors shell out cash for Egyptian citizenship?’, Al-Monitor (15 August 2016)

[xix] David E. Sanger, ‘Kerry meets Egypt’s leaders, and where are reporters? Corralled at the airport’, New York Times (18 May 2016)

[xx] Torie Rose DeGhett, ‘US Arms Exports to Egypt: I Wish I Knew How to Quit You’, Vice (5 November 2015) / ‘Egypt signs 2 billion euros worth of deals with France’, Mada Masr (19 April 2016) / Jack Shenker, ‘Sisi comes to London: why is David Cameron welcoming Egypt’s autocrat to the UK?’, Guardian (31 October 2015)

[xxi] ‘PM phone call with President Sisi of Egypt’, Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street (3 August 2016)

[xxii] Michael Georgy, ‘In Egypt, an Italian student’s research stirred suspicion before he died’, Reuters (4 August 2016) / ‘Italian interior minister: Student Giulio Regeni was subjected to `animal-like` violence’, Mada Masr (7 February 2016)

[xxiii] ‘Amid political tension over Regeni case, Italian energy projects in Egypt power ahead’, Mada Masr (24 April 2016)

[xxiv] Isabel Esterman, ‘On Giulio and the cost of doing business in Egypt’, Mada Masr (10 February 2016)