Twenty-five journalists flew on a chartered plane down to Guantánamo Bay on October 22, 2010, to report on the case of Omar Khadr, the Canadian 24-year-old who has been in US custody for one-third of his life. We would have been on the island (Cuba) a week earlier but for a sudden change of plan—again. The original original plan, let’s call it Khadr Trial 1.0, had a start date of August 12, and indeed the trial did start on that day. But at 4:00 p.m., Khadr’s military defense lawyer, Lt. Col. Jon Jackson, collapsed in the courtroom. The trial was suspended. Khadr Trial 2.0: The Resumption would have begun on October 18. But on October 14, word came down: a plea bargain is in the works. On October 24, Khadr’s Canadian lawyer Dennis Edney gave a short press conference announcing that a plea bargain has not been agreed to by all parties. According to him, the trial will resume on October 25. Over the weekend, we took a tour of the prison—in official parlance, “the detention facility.” These images were shot by a photographer who wishes to remain anonymous; all of them have been cleared by operational security, although others were censored and deleted, including a full frontal head shot of Khadr in dark shades which he wears because his war-damaged eyes cannot bear the bright sunshine.

[Entrance to Camp 6]

As we entered the facility, we secured our media badges, placing them inside our shirts so that they were not visible. Journalists are always required to secure their badges whenever photos are being taken. No official reason has been offered to explain the logic of this rule, so the journalists are free to speculate: one theory is that the Pentagon fears that if an image of the badge appeared in public, al-Qaeda could duplicate it and infiltrate a bogus “reporter” onto the island to commit mayhem or worse. However, since journalists must always be accompanied by military escorts, for such a plan to work, al-Qaeda would also have to fabricate and infiltrate a bogus soldier.

Our tour guide was the deputy commander of the Joint Detention Group, Lt. Col. Andrew McManus. He answered our questions in a forthright manner, although he is limited by what he is not permitted to tell us—for example, information about the conditions of specific detainees.

[Lt. Col. Andrew McManus]

Camp 6, our first destination, is a pre-fabricated medium security prison that was transported from the mainland. It houses prisoners deemed to be “compliant” who live in communal settings within their blocs. They can cook and eat together, and they can spend up to 20 hours a day out of their cells.

[Communal living in Camp 6] [Waiting for lunch in Camp 6]

Currently, there are 90 people in Camp 6. Compared to Camp 4, which also houses compliant detainees, Camp 6 is a best-of-both-worlds arrangement as far as indefinite detention goes: it offers the privacy of individual cells.

[Model cell in Camp 6]

Another advantageous feature of Camp 6 is air conditioning. Recently, many from Camp 4 requested to move to Camp 6 because, as McManus explained, it gets hot down here. In Camp 6, occupants of the five blocs are grouped according to whether or not they want to live in the proximity of TVs; two of the blocs have radios only. According to McManus, many Afghanis prefer to be indefinitely detained without TVs.

[Press talking to McManus in Camp 6]

About 40 percent of the total prison population takes advantage of education classes. The student-prisoners are secured in their classrooms with ankle shackles affixed to the floor.

[Shackles in classroom]

The most popular courses are computer training and life skills classes. The latter includes “managing your personal finances” and “resumé building.”

[Computer classroom]

In addition to classes, prisoners have access to library books, games, paper and pens. The latter are edible—well, actually, “digestible” in case swallowed; they are made of hardened fructose.

[Edible pens]

Outside Camp 6 we passed a mounted plaque commemorating its establishment in October 2006 with the embossed inscription that reads, in part: George W. Bush, President and Donald H. Rumsfeld, Secretary of Defense.

[Mounted plaque]

Our next stop was the prison hospital where our guide was the unidentified Senior Medical Officer, who shall be referred to here as Dr. SMO.

[Senior Medical Officer at GTMO hospital]

The 12-bed facility, according to Dr. SMO, is “what you would see in the US in what you’d say is a ‘community hospital.’” He added that the patient-to-provider ratio is probably better than in some mainland community hospitals. Inside the hospital, at the first desk sits a multi-linguist with medical training who can understand and interpret for prisoner-patients. The second desk is a guard station. Guards accompany prisoners at all times in the hospital. The intensive care unit contains two beds inside cages.

[Intensive care unit]

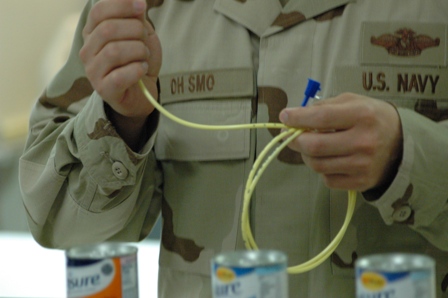

Dr. SMO offered vague and scripted answers to journalists’ questions about the current state of medical health in the prison, saying, for example, that the hospital treats common ailments and diseases found in society, like diabetes and high blood pressure. Asked whether the hospital had performed any recent amputations or whether anyone was undergoing chemotherapy, he declined to respond. The most persistent and pervasive “medical” issue at GTMO has been hunger striking; over 100 prisoners have refused food over the years. Force feeding chairs were introduced in January 2006. Today, according to Dr. SMO, “less than ten” are fed Ensure through their noses.

[Ensure display]

Dr. SMO explained that he had himself put through the tube-inserting procedure to understand how it feels. The tube is dipped in Lidocaine jelly and then olive oil to numb and lubricate the nasal passage. When it reaches the stomach, drip feeding ensues. The most popular flavor of Ensure is Butter Pecan. Question: “But how can they taste it?" Answer: "When they burp.”

[Feeding tube demonstration]

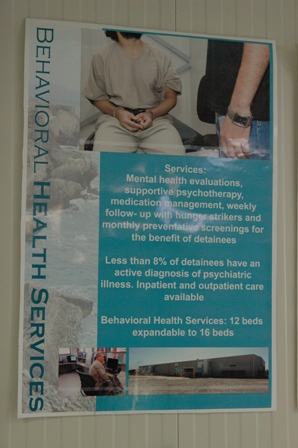

On our way out, we passed through a room filled with posters about the various kinds of medical services provided through the hospital, including one about behavioral health which reads, in part: “Less than 8% of detainees have an active diagnosis of psychiatric illness.” We were told some (undefined number of) prisoners spend “protracted time” in the behavioral unit.

[Behavioral health poster]

Our last stop was Camp 4. Built in 2003, it was the first communal living compound with four bays (i.e., rooms) per bloc and approximately five prisoners per bay. Currently 40 prisoners live in Camp 4.

[Entrance to Camp 4]

In the open-air communal area, prisoners were preparing their lunch.

[Communal living in Camp 4]

[A prisoner in the communal area of Camp 4]

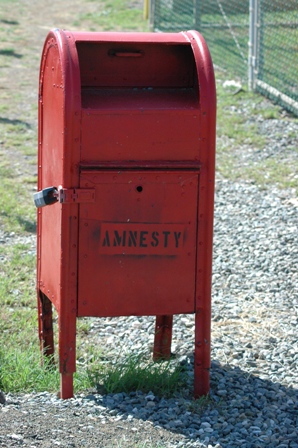

As we left the prison and returned to our van, I spotted an odd sight in the parking area: a red mailbox with the word “Amnesty” embossed on it. None of our escorts could explain what it is for.

[Amnesty mailbox in parking lot of GTMO prison]