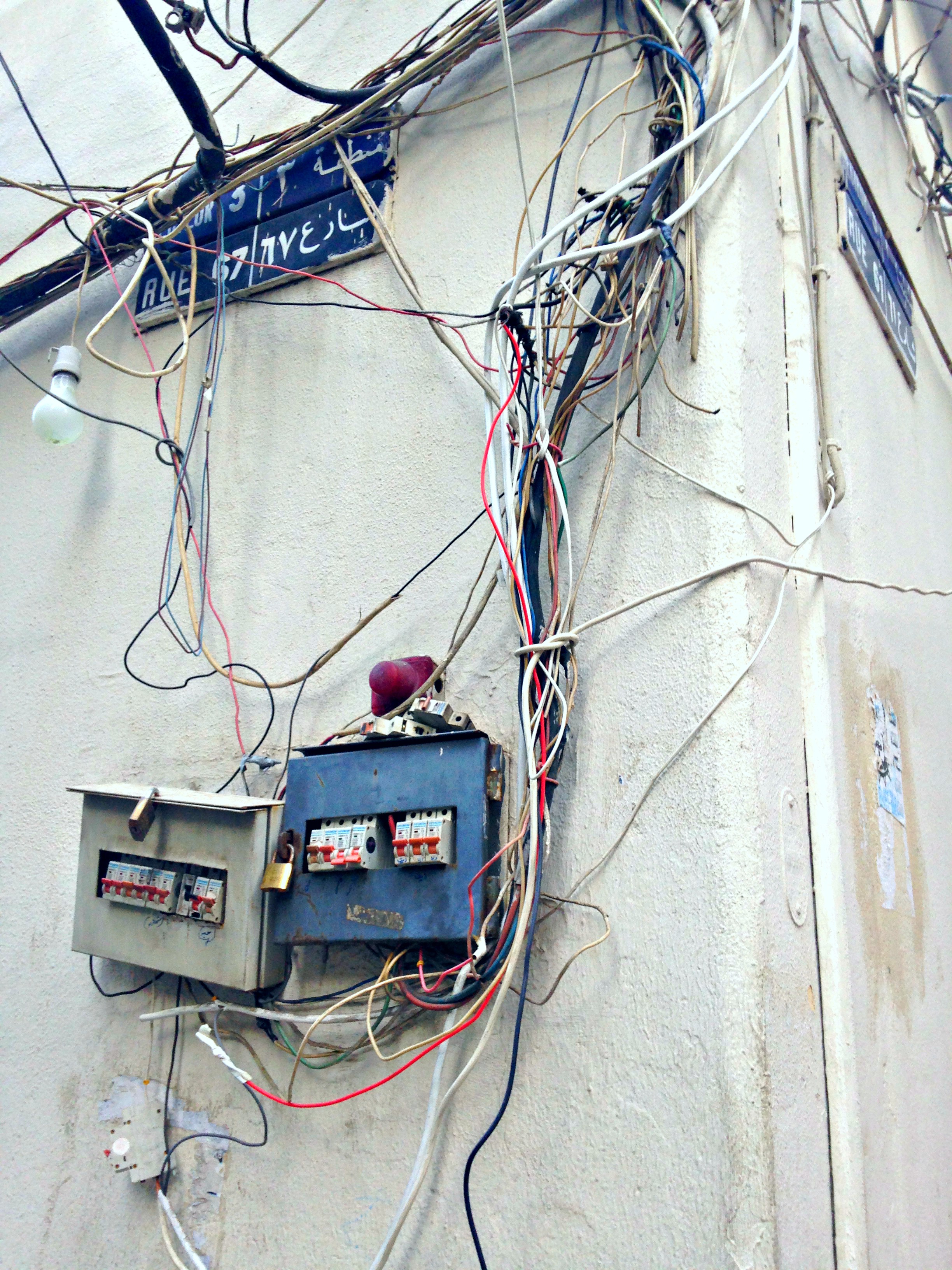

As filmmakers and researchers working on electricity in Beirut, it is tempting to become too attached to the visible, namely electricity wires that drape the city like garlands, dangerously gaping down at pedestrians, changing their paths, forcing detours. The ubiquity of wires stretching like lianas from rooftops, or hanging heavily in overgrown bunches from leaning poles, inches from your head is difficult to avoid. The crowding of sky and street by intertwining cables, whose origins and destinations are difficult to trace, is one of the most distinctive features of the city’s urban landscape, and a very explicit metaphor of Lebanon’s chronic electricity crisis. The wires dance and dangle in front of your eyes, providing a constant reminder of how manifest this crisis is, of how electricity is both abundantly visible, and yet in scarce supply. The electric jungle is then first of all a contradiction: the abundance of wires and fuse boxes is the visual evidence of a fundamental lack, of infrastructural deficiencies that keep Beirutis in (de)regulated darkness. It is also the evidence of a system that pushes most to pay over the odds (to private generator providers), leaving them exposed to financial exploitations, whilst it forces the poorest, who often have very limited access to state electricity (if any altogether) to rely on or invent polluting and costly ad-hoc solutions.

As with every (visual) metaphor, Beirut’s wired scenography is one that should be treated with caution, for the romanticism that could be attached to the creative resilience of Lebanese citizens who continue to live in the midst of State’s inefficiencies and inequalities, internal conflicts and geopolitical struggles, may not be as rewarding as one would think at first.

Those who practice visual media know that the production of images often hangs on the precarious balance between visibility and invisibility, between what takes place in, and off the frame. Media that owe their existence to a certain, more or less oblique, alliance with, and dependence on, physical reality (photography, film) touch this issue with a heightened sense of urgency. The visible sign, which must be obstinately sought and captured is often no more than a surface. Often the visible evidence conceals more than it illuminates.

[Tangle of wires in Hamra. Photo by Abi Weaver, 2016]

Background

The question of electricity in Lebanon is one that has attracted considerable attention, with research focusing on institutional reform of the sector, with insights on urban development and governance, health implications of diesel generators’ emissions and sustainable energy generation. The problem of electricity supply in Lebanon has a long history, one intrinsically intertwined with Lebanon’s socio-political system, its economy, geo-political status and the conflicts that have affected the country since its independence. Already during the years immediately following independence, questions of electricity provision and cost to the consumer played an important role in the public debate about economic development, utilities, and transparency. As Ziad Abu-Rish notes, power cuts even in the late 1940s were already a problem, as was the price of electricity. Consumers, politicians, and private investors in the sector had different, yet overlapping, interests in pressing for government intervention. State intervention in this debate led to a fundamental shift in the early 1960s as part of a more general programme for the universalisation of services and infrastructure–including electricity–spearheaded by the then president Fouad Chehab. This process culminated in the creation of Électricité du Liban (EDL) in 1964. Whilst the provision of electricity in Lebanon was never therefore without its problems, it seems clear that various cycles of violence and political unrest have caused a progressive deterioration of the infrastructure that the country is yet to recover from. During the fifteen years long civil war (1975-1990), the grid was often explicitly targeted and had to be repaired constantly. It is reported for instance, that during the siege of Tall al Zaatar in June 1976, the main power cable supplying Beirut was hit leaving the capital without electricity for more than four months (Kassir 1994: 218). Whilst the civil war played a decisive role, the fifteen years conflict can be seen as just one moment in a longer history. Throughout the years following the Taif Agreement, Lebanon and Beirut have been directly affected by various rounds of conflict with Israel, which focused on damaging power stations and communications. In the summer of 1997, Israeli air strikes, in retaliation for Hezbollah’s activity in occupied south Lebanon, targeted overhead lines and the Jiyeh power station, twelve miles south of Beirut. Commenting on the choice of targets a spokesman for prime minister Netanyahu said "the message to Lebanon was this: if we can’t have tourists, you can`t have electricity." In 2000, the then president Ezer Weizman summarized the practice of infrastructural war by saying: "We shall plunge their world into darkness." The power stations at Bsalim (from where Israeli troops had reportedly stolen maps during the 1982 invasion), Badawi and Jiyeh were repeatedly shelled in May 2000 and July 2006.

In addition to this, the post-war reconstruction has added new layers of spatial and social differentiation through rehabilitation policies (new infrastructural work), and the management of networks policies (fees collections, theft repression). Central Beirut receives three hours rolling cuts per day, whilst areas in Greater Beirut such as Chiyah, Bourj Hammoud, Sin el-Fil, can get up to twelve hours power outages. Today, power outages are part of daily life in Beirut, leading to an array of strategies for maintaining desired levels of service. The need to gain access to electricity, and to secure stable supply have become part of the everyday, and has led citizens to adapt their lives according to the type of electricity connection they have at a particular time.

During the civil war, diesel-powered generators were introduced onto the market to subsidize the state’s failing attempts to provide sufficient energy to its citizens. The gap in electricity supply, as a consequence of the ongoing conflict in Lebanon, has brought on the growth of informal networks of private generator entrepreneurs (PGEs) that complement the electricity provided by EDL, with most people and businesses therefore paying two bills, in many cases a cheaper one to EDL ($0.0958 per KwH, this tariff has been frozen since 1994), and a more expensive one to the PGEs (at least $0.45 per KwH) (El-Hafez 2016: 4). Similarly to much of the dynamics of Lebanese politics in relation to "power," the status of the PGEs remains a contested area.

.jpg)

[Tangle of wires in an eastern suburb. Photo by Daniele Rugo & Abi Weaver]

Diesel generators ensure that those who can afford the often extortionate prices of subscription (which might include maintenance and refill) can have twenty-four hours of electricity in their homes and offices. The case of Dima is exemplary. She lives in a brand new apartment in southern Beirut, and explained that she pays a figure close to one thousand dollars per month on various electricity bills. Her flat is not connected to the national grid due to a dispute with the property developer, so the entire building has to rely on two diesel generators, and an informal electricity connection from the apartment block next to it, paid for and allegedly provided by an ex-army general. It is not easy to verify these stories, considering how much is at stake. We have not been able for instance to speak to the supplier from the building next door (the "general"), and we have not been able to verify the reasons why the property developer has not connected the new apartments to the national grid. However, what seems to be beyond dispute is that private generators, which create an estimated income of two billion dollars per year (El-Hafez 2016: 41), have consolidated themselves as an expensive, yet reliable way to get electricity. This is reflected in the increasing reliance of Lebanese households on generation. According to a report by the World Bank, up to fifty-eight percent of households in Lebanon use some form of self-generation.

The Invisibility of Electricity

During our first fieldwork trip, we introduced our project Following the Wires to Talar, a resident of Bourj Hammoud. After our brief explanation, Talar asked us: "Why are you so interested in electricity? After all Lebanon has a massive rubbish crisis, one million Syrian refugees; we’ve been without a President for more than two years, our economy is struggling and the cost of living keeps going up, we’ve been at war until not long ago. Why are you interested in electricity with so many more important problems?" The answer is precisely that electricity provides a starting point to understand many of the issues at stake. By focusing on electricity supply, the project aims to show how discrepancy in services is not only the result of technical vulnerability but an indicator of social, political, economic and sectarian fragmentation caused by conflicts over the years. The goal is to make visible–through research and film–the electricity crisis, and its relation to socio-political and economic power structures, by focusing on everyday responses to power cuts, and other issues that usually go hand in hand with the inability of households to afford electricity. The income gap, and more broadly socio-economic inequalities, play a crucial role as far as electricity supply is concerned. On the one hand, the middle classes find themselves forced to acquire almost technical skills–becoming quasi-electricians, in order to bring "power" to their household. For most of them, the message seems to be: if you can pay, you can have it. On the other hand, according to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Human Affairs, one in two people in Lebanon are understood as being "in need," either Lebanese nationals living under the poverty line, or refugees (Syrians, Iraqis, Kurds, Palestinians fleeing Syria), living in urban centres, in rented or squatted accommodation. These groups are unlikely to be able to afford private subscriptions. Understanding how they, the often invisible non-citizens and Others, manage to bring "power" into their homes, and how they cope with outages, will be the primary focus of the next stage of our filming process.

[Fuse box in an eastern suburb. Photo by Daniele Rugo & Abi Weaver, 2016]

Following the wires leads us to uncover areas where the electricity issue is even more visible, whilst others remain opaque, covered up by the relationship between the illegal diesel generator trade and party politics, theft, grabbing, and hacking. The visibility of the electricity crisis, the prominence of wires and creative fuse boxes that furnish the urban environment, is balanced by a much less visible set of ad hoc solutions and systemic practices. It is this balance between the visibility of electricity in the streets and the invisibility of the practices and conflicts that are consequences and instigators of this crisis that makes visual, anthropological and geographic research particularly challenging. Wires and fuse boxes, the latter often the work of extraordinary electric craftsmanship, are the most visible reminders of the situation, but following them means inevitably to disclose areas of invisibility that the camera cannot access. Following the intricate weft of cables around Beirut has led us so far to two faces of this invisibility: illegality and normalization. The ambiguity over private generators is one such area. Generators of various sizes are often visible around Beirut, but this visibility once again opens up areas of opaqueness. Until now PGEs are officially illegal. However, the government has published guidelines for maximum pricing of subscriptions, encouraging local authorities to enforce regulation on enterprises operating in their respective jurisdictions, and effectively legitimizing their role and existence. From accounts we have gathered in Beirut, private-generator providers often also have links of various kinds with political parties dominant in their respective neighborhoods. These seem in many cases to replicate the sectarian and political divisions at work within Lebanon at large. In one particular occasion, a local mukhtar told us unequivocally that no generator person would speak to us, whether on or off camera. Normalization is another area of invisibility. Most people in central Beirut have become so accustomed to the use of generators that they do not really adjust their everyday life, knowing that the switch from EDL to the private generator might take between ten seconds to a minute. The switch goes almost unnoticed. The adjustment is invisible. The question, as filmmakers and as researchers, is then how to "make visible" the invisible "power" that subtends the electricity crisis playing out in plain view in Beirut and its suburbs?

[Wires running between two buildings in an eastern suburb. Photo by Daniele Rugo, 2016]

References:

Samir Kassir, La Guerre du Liban. De la dissension nationale au conflit régional, 1975-1982 (Paris-Beirut: Karthala-CERMOC, 1994).

Ramzi el-Hafez (ed.), Oil and Gas Handbook (Beirut: InfoPro SAL, 2016).