For a young scholar, a figure like Janet Abu-Lughod can seem almost impossibly prolific. Among the fields to which Abu-Lughod made celebrated contributions, we find urban sociology, world systems theory, studies of colonialism, and racial injustice (from Palestine, to the United States, to Morocco!), the history of Cairo, globalization, the politics of neighborhood preservation, and the cause of women in academia. Her refusal to compromise between breadth and depth seems to contrast with our own academic worlds, where curiosity is confined to ever-narrowing niches of the job market. Yet, as we are reminded by Sherene Seikaly, who authored the introduction to a 2014 collection of essays that Jadaliyya published to celebrate Abu-Lughod’s life and work, “As a thinker, writer, researcher, and scholar, woman and activist, the model she offered remains very much alive.”

Unlike the authors of those heartfelt essays, I never had the pleasure of meeting Janet Abu-Lughod during her life. But, in 2016, I did have the good luck to discover just how lively her example still is. This opportunity came through designing and leading a series of discussions around works drawn from her personal library, a collection of over eight hundred books located at the Columbia Global Center in Amman. My role in the seminar came about through a collaboration with Studio-X Amman and Sijal Institute for Arabic Language and Culture. As an extension of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, Studio-X is a global network of scholarly and cultural platforms, part architecture studios, part academic laboratories dedicated to thinking about the future of urban environments. The library itself was made available through the generosity of Lila Abu-Lughod, Janet’s daughter, and herself a scholar of uncompromising political and intellectual commitment, who, together with her family, gifted the volumes to Columbia University.

[Picture 1: A small portion of the library’s variety at Studio-X Amman.]

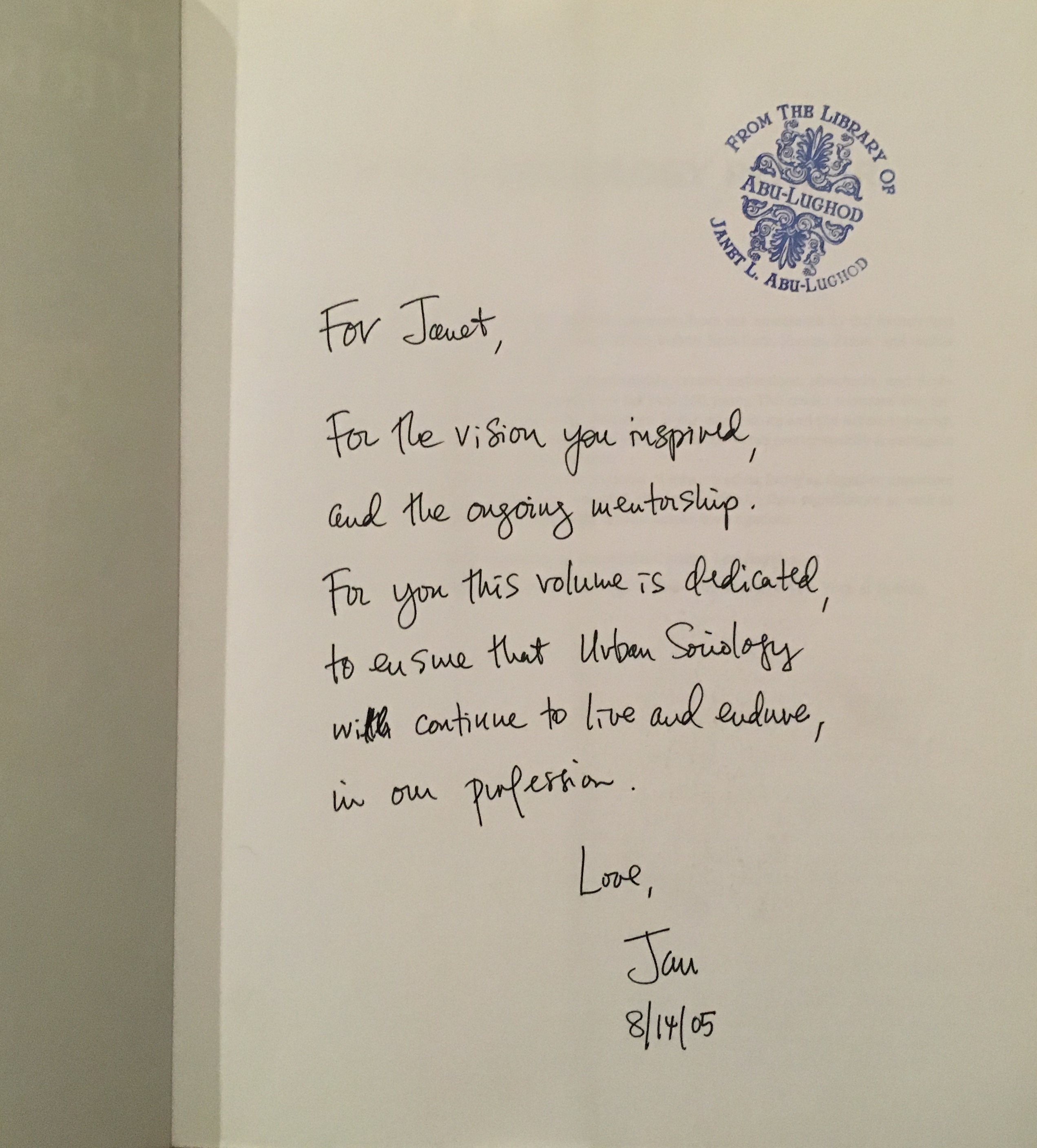

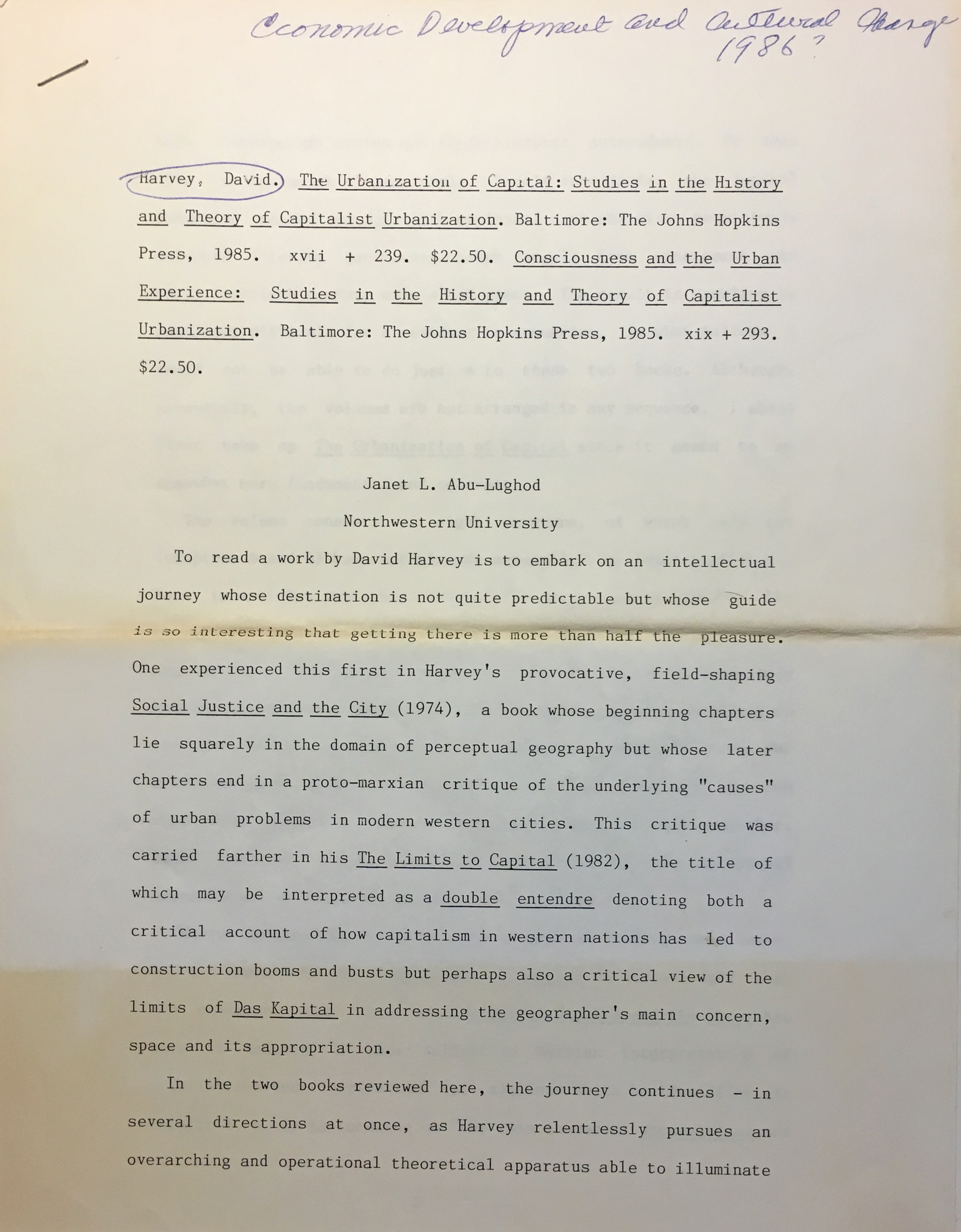

The library exhibits the broad arc of Janet Abu-Lughod’s biography and intellectual genealogy. Arrayed across three large shelves that reached well above my head, I found everything from tomes to travel guides covering the east and the west, the ancient and the modern, the slum and the utopia, and everything in between (picture 1). Were I working from a list of titles in some kind of index, the task of narrowing-down a manageable number of chapters and selections for six meetings would have been impossible. Many of the books, however, recommended themselves through the highly personal traces they contained. Some works spoke of the care with which they had been read through Abu-Lughod’s own anything-but-marginal marginalia: schemata scribbled in highlighter (picture 2), critical underlining on an argument that came up short (picture 3), or praise of an author’s “good bon mot” (picture 4). Just as many presented themselves as gifts honoring Abu-Lughod’s mentorship and influence (picture 5). And a few gave up totally new discoveries, like a copy of David Harvey’s The Urbanization of Capital that contained the original typed manuscript of Abu-Lughod’s review of the book (picture 6).

[Picture 2: Janet Abu-Lughod’s outline of Edward Hall’s arguments aboutthe perception, use,

and meaning of space in The Hidden Dimension.]

Those traces suggested an itinerary to be followed in our six-week course. We passed through Abu-Lughod’s formation in the Chicago School of Sociology, her time in Cairo, and her collaborative work documenting neighborhood activism while at the New School. Unfortunately, there wasn`t enough time to take every path--most disappointing was not getting to discuss those books that may have inspired and were inspired by her work on colonialism and apartheid in Rabat, and in Palestine. For those with the opportunity to visit the Columbia Global Center in Amman, I highly recommend taking a day to chart your own course through the library first hand.

[Picture 3: Abu-Lughod suggests Immanuel Wallerstein has failed to recognize a world system predating European hegemony in the margins of The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century.]

To discuss the texts, we assembled a small but diverse group of readers. We ended up with a mix of social scientists, architects, urban planners, and artists from both Jordan, and abroad at all stages of their careers (but most much more accomplished than I!). The variety of knowledge and experience these participants brought to the table ensured that discussions were pleasantly free of the kind of disciplinary hedging that accompanies most academic workshops and seminars. Instead of arguing about other people’s arguments, we told stories about the neighborhoods we grew up in, discussed specific problems facing the communities in which we worked and lived, or shared insights from our professional and academic lives.

[Picture 4: Complimenting Mike Davis on his use of the term “postindustrial” in City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles.]

These discussions had a transformative effect on classic works that are often regarded as dusty, survey-course artefacts of intellectual heritage. By putting St. Clair Drake’s Chicago, Georg Simmel’s Berlin, or Abu-Lughod’s Cairo into play alongside our own perspectives, the texts became lively examples that spoke to our own concerns, which ranged from the effects of mixed-income housing in Singapore, to performing public art in Amman. Studio-X Amman’s own research was brought into the seminar by a presentation of the Frozen Imaginaries project on planning and abandonment in Amman alongside the boom-and-bust London of Harvey’s Urbanization of Capital, and Abu-Lughod’s response to Harvey’s work. In all these sessions, the specificity of our, and the authors’ perspectives led us to better appreciate the usefulness and the limits of the arguments in the books for constructing our own situated visions, whether as social scientists, artists, or architects.

[Picture 5: Jan Lin dedicates The Urban Sociology Reader, Second Edition, of which he served as co-editor, to Janet Abu-Lughod.]

Abu-Lughod is herself remembered for rejecting received disciplinary typologies like “The Islamic City” or “globalization” in favor of careful attention both to each city’s individual history, and to its distinctive interconnectedness within broader systems. In one of her last pieces, which we read in the final week of the course, she writes that she always told her students they would need many different ideas drawn from various disciplines “in their toolkits,” but also that, “the only theories worth having are theories in action, in use, for the purpose of understanding and explaining real thing.”[1] And I’d like to think that our group’s own eclectic empiricisms were keeping in the spirit of this lesson.

[Picture 6: The first page of a typed version of Janet Abu-Lughod’s review of two of David Harvey’s works,

the final version of which later appeared in Economic Development & Cultural Change, January 1988.]

Yet although our own, as Abu-Lughod put it, “varieties of urban experience”[2] stood front and center, our discussions returned again and again to our common ground in Amman. Our meetings were held at Sijal Institute, a cultural center located in a historic home atop Jabal Amman. From the homes’ gardens, where we would take our cigarette and tea breaks, one could enjoy views of the surrounding hillsides in the evening. I don’t know what Janet Abu-Lughod thought of Amman, but reading her work in that place did make me speculate about what special lessons this city had to teach.

Certainly, Amman is a city that resists easy typologies. Its shading in 20th-century sandstone traditionalism belies the layers of variations brought by émigrés, guests, and settlers who with each successive arrival reshape its landscape. From the historic Circassian hillside homes around the Roman Amphitheater to the arcades where one can enjoy home cooking from Tamil Nadu just above the main avenue of the historic downtown, Amman’s complex topography offers endless distinct vantage points from which to consider matters of importance to all cities: not just immigration but also water use, transportation, real-estate speculation, and more.

Abu-Lughod’s work reminds us that all cities have something to teach us because each one acts as a node in complex systems of travel and exchange. My own dissertation project, an ethnography of the social and professional lives of Amman’s affluent Iraqi arrivals, has benefitted tremendously from the model Janet Abu-Lughod offers. Rather than orienting my work towards the international system of humanitarian intervention, I’ve come to learn about the longue durée of travel and trade between Iraq and Jordan, how Amman has been shaped by its neighbors’ investments of capital, expertise, and labor, and about the challenges and opportunities to build lasting connections on the periphery of the hegemonic West. Returning to the observation with which I began this essay, I have often felt the pressure to narrow-down my work: to select a single theoretical frame, to demonstrate a project’s “feasibility” and to market it to a small group of specialists. By contrast, the seminar was an opportunity to break frames open, to engage in dialogues that overturned expectations, and to let curiosity run well-over budget. I hope that the success of this experiment can inform the next iteration of the seminar in Amman, beginning in Summer 2017, and inspire readers in all cities to revisit the works of Janet Abu-Lughod through her extraordinary library.

[1] “Grounded Theory: Not Abstract Words but Tools of Analysis” in The City Revisited: Urban Theory from Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York edited by Dennis R. Judd and Dick Simpson, 20011, p. 21

[2] “Varieties of Urban Experience: Contrast, Coexistence, and Coalescence in Cairo” in Middle Eastern Cities. Lapidus, Ira M. ed. Berkeley: The University of California Press 1969