John Halaka: Ghosts of Presence/ Bodies of Absence

Gallery One, Ramallah, Palestine

21 March – 20 April 2017

Upon encountering John Halaka, one cannot ignore the burdens he appears to carry on his shoulders. He exhibits the features of a haunted man, who struggles with loss, exile, displacement, and an ongoing absence, perhaps an irretrievable one. His figure is dominant in most settings, despite his constant attempts to disappear, but when he speaks in carefully chosen words, he comforts with friendly charm, depth of perspective, and embracing thoughtfulness. While his works firmly stand alone as a record of the artist’s labor and his authentic vision, his Palestinian identity transforms the encounter from a meeting with burdens of history into an experience of possibilities. To understand this exhibit, one must consider a shared psychological and physical state between the subject, the artist himself, and the viewer. Namely, John Halaka is, in the ontological sense, all three: the creator, the created, and the witness. His subjects and works also share this ontological quality. In many respects, they are all one.

The works in Ghosts of Presence/ Bodies of Absence simultaneously project into the past and the future, creating a contemporaneity, which deepens the present moment. Halaka creates theatrical scenes that realize a shared dimension between bodies and spaces in an interactive intimate relationship, which otherwise must cross hostile territories for the encounter to manifest. By imaginatively reconstructing the relationship between distant bodies and occupied places, he employs the virtual in an intellectual and visual rendering to remake Palestine from its shattered fragments of body, intellect, identity, culture, and stone. The production of this extensive series at hand can only be seen as an act of collecting shrapnel in the aftermath of total destruction. Remnants and remains, virtual and tangible, collide to perform an elegant dance of sorrow and resistance.

The outcome is a haunted stage that first existed in his imagination. Over a period of several decades, the players transcended the limits of territoriality, festered in the devastation of collective trauma, chipped away at concrete blockades, immersed themselves in wells of memories, imprinted stories into each other’s bodies, pierced narratives into their hopeful eyes, and bended time with the soft wrinkles in their aging faces. Their appearance debunks millions of words, written in offence to their existence and belonging. Their absence attacks the logic of erasing rhetoric. Their disappearance haunts layers of lands and stones. They emerge unexpectedly to show that their presence is perpetual and only tautological in the minds of denialists. These players share the stage and speak a silent language, understood by each other and felt by the audience. Halaka reproduces the backdrop, and then places the player within and upon it until the stage and the player become indistinguishable in function and narrative. Does the stage live in the player or the player live on the stage? This question is reminiscent of a historic Palestine that survives at home and in exile.

But it was not always like this! To walk through the exhibit is to walk in Halaka’s shoes as he attempts to re-populate ghost-villages, once bustling with living and speaking bodies. His subjects are real people, displaced from their homes, placed into refugee camps and temporary homes despite an illusion of some permanence. He encountered them in the flesh and permitted himself to carry their burdens, synthesizing their memories, presences, stories, and the passage of time into a collective silent dialog. Like an experienced playwright, he writes a script ridden by conflict, only to realize that he is but a conduit, which transforms energy into image. Against traditional representations, the psychological and emotional presence of the refugee conjures the political realm through tragic elements. In this compositional device of staging ghostly figures in their original home, Halaka unifies shattered bonds and recollects disconnected fragments in humanizing images.

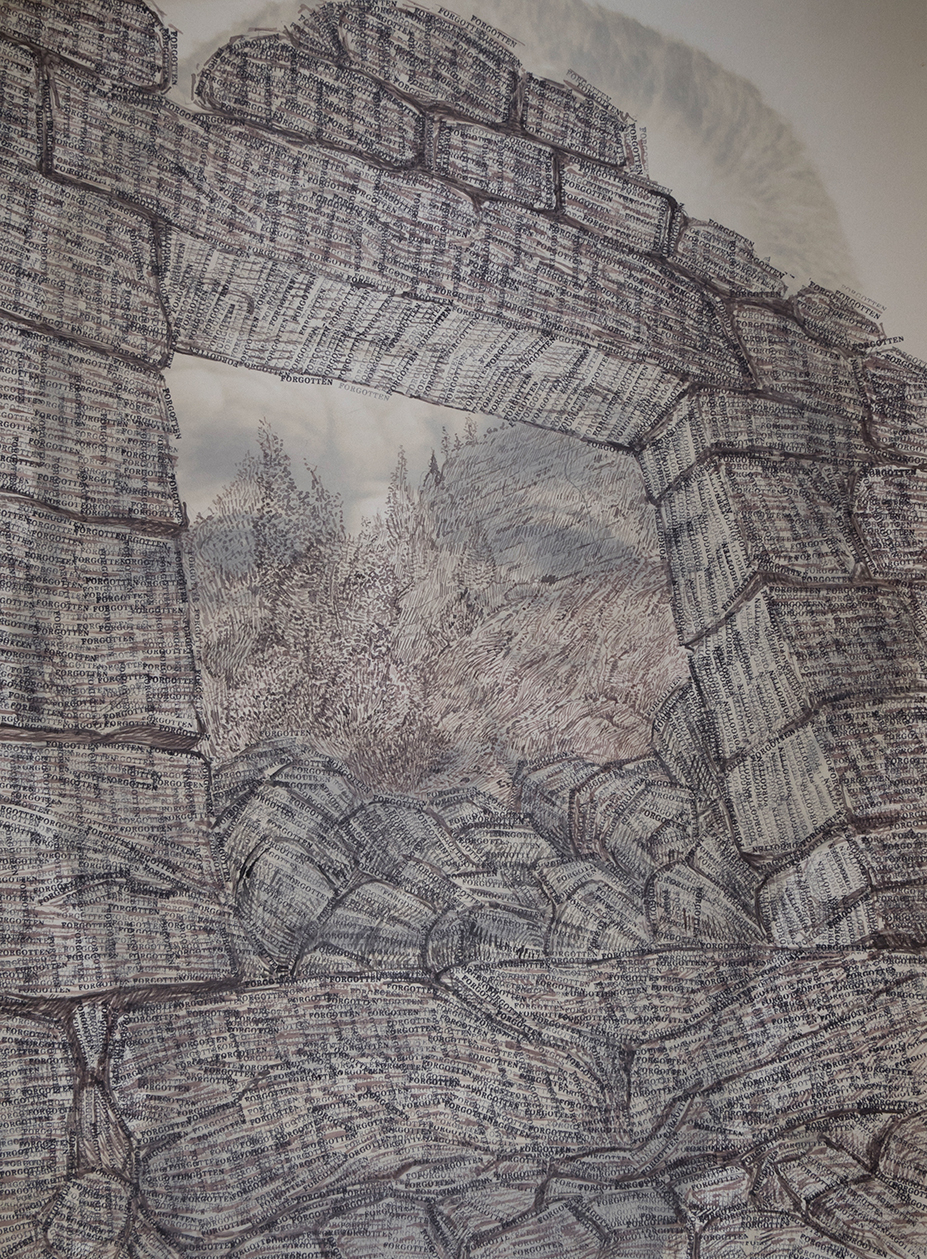

[Ghosts of Presence/Bodies of Absence #11 (2016) by John Halaka. Image copyright the artist]

[Ghosts of Presence/Bodies of Absence #11 (2016) by John Halaka. Image copyright the artist]

Halaka’s stages of the homeland exercise a basic human right: the belonging of a body to its home. Upon walking through depopulated villages, one has the distinct feeling of unfinished business. The villages have the qualities of organic growth from a history of conquests and mixed lineages of a people from and of the land. The architecture and urban planning often combine a historic footprint with the living toils of Palestinian labor over centuries, an intermixing of experience and architecture. Nowhere does the interruption of Palestinian history appear more forcefully than in villages that beg for their inhabitants to return. Halaka observes the interruption and acknowledges it but does not seek to recreate the village as it once was. Instead, he sees a heartbreaking reality: the home has become a representation of the absent body, taking on its features in the process. The work counters the artist’s intuition of imaginatively recreating the living past in inanimate form; rather, it produces an architecture sustained by the bodies, faces, and spirits of its builders.

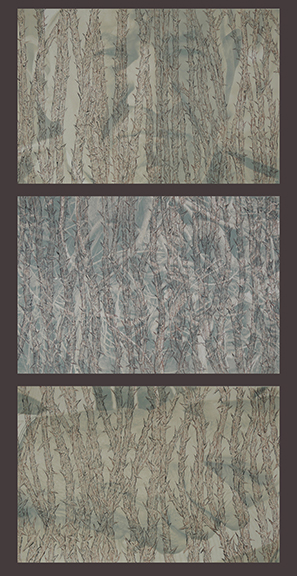

This exhibit does not in any way recreate the past, thus becoming an exercise in anti-nostalgia. Halaka recognizes that the village can no longer exist as it once did. The brilliance of the work emanates from his painful recognition of the passage of time. The vibrant village has aged, as did its people. They both lived in isolation from each other through decades-long, forced separation. To re-join their young versions in a photographic experiment would deny their trauma and evoke a desire for a golden age that perhaps cannot be replicated as it does in memory. The viewer sees two parallel timelines at work: the aged body and the deteriorating stone. The superimposed timelines prompt a necessary imaginative rumination on what happened since the village once bustled. They also instill a feeling of inevitability: the colonial conditions that caused the trauma continue to enforce the separation and the aging bodies and stones continue to deteriorate until the vibrant relationship between Palestinians and their homes no longer can be reconstructed. As the people die and stones sink into the earth, the village progressively dies as well. This inevitability breeds an urgent call to forego nostalgia and to attempt to alleviate the pressures of ongoing erasure.

[Ghosts of Presence/Bodies of Absence #43 (2017), triptych, by John Halaka. Image copyright the artist]

[Ghosts of Presence/Bodies of Absence #43 (2017), triptych, by John Halaka. Image copyright the artist]

Having set the stage, the players, the historical argument, dialog, and the call-to-action in motion, Halaka explores theatrical elements to communicate the complexities of the images. Natural lighting sweeps the stage, often in the form of shadows. Windows and doorways permit sunrays to illuminate stones and cacti, asserting the interconnectedness of built and natural environment. Ranging from gray daylight to bright days in gray hues, the choice of lighting by designed shadows inspires a mental consideration of temporal affects. The parallel timelines and the separate spaces occupied by homes and homeowners appear in the specifically lit faces, either appearing as brightly illuminated or darkly lurking in the distance. On occasion, empty spaces in the background are lit partly by faces, suggesting an abstract light energy, reflected by the characters who behave like a light source for the broken buildings. In some scenes, the density of chosen words like memory, survival, sacrifice, remember, and return, throws a shadow on otherwise bright stones. By consciously lighting the stage in complementary hues of gray, Halaka insists on the unnatural state of the village and its exiled population.

The theatrical element of costume connects the form and architecture to a people. Adorned in traditional Palestinian costumes, the players meld into the scene, marking it with a disappearing heritage. Women in hijab, young and old, form a foundation for reflection upon the village. Men in traditional headwear, hattas, look into their homes or at them from vast distances. Drawn from ethnographic research and in-person interviews, the greatest depicted costumes adorning the players are the wrinkles of time, the emotional connection to home, and the Semitic features of a native people. These costumes of the players’ bodies cannot be sewn, replicated, or sold. They have developed over centuries of toil and been imprinted into their blood. By successfully ornamenting the bodies in traditional threads, and then netting the sacred spiritual lineage of people and land, Halaka captures a unique signature aesthetic characterized by patience, love, and longstanding belonging. These players are not manufactured and packaged into character; rather, they are the character.

Ghosts of Presence/ Bodies of Absence functions as a performance of history on two levels. First, characters reclaim ethnically cleansed villages within the works as they are imprinted on the architecture and perceived to be contouring them in a visible overwhelming embrace. On this level, layers of transparencies melt onto each other rendering the origin indistinguishable from the offspring. The characters–faces and bodies–hover above and within the setting, like spirits ghosting the space, haunting it, and reshaping it into their features. But the image of a home and the face of a homeowner are profoundly intertwined, each emerging out and fading in, blurring the focus, to establish the spiritual inseparability of stone and person. Does the stone haunt the person or the opposite? Does the ghost of home haunt the refugee or the opposite? This presence of the characters, carrying their own narrative of a historical journey, tells the story of a people haunting and haunted by specters of displacement.

On the second level of this performance, the audience does not walk through the village, gazing at remnants of near annihilation; rather, they experience the gaze of a people, often demanding an explanation for inaction, silence, and complicity. On this stage, the actor stares directly into the eyes of the audience, dropping any pretense of performance. Simultaneously, to the sympathetic audience member, the character gazes at its home along with the viewer, sharing the same scene and contemplating the same home. On this walking tour of a people’s internal dialog with home, from piece to piece in the gallery, the audience is challenged to reveal its prejudice or solidarity. The extraordinary volume of faces and sealed lips forces the onlooker to extrapolate on the millions of individuals who have not yet been depicted, those who died in exile and the ones yet to be born. By the end, an emotional state overwhelms the audience and the ultimate purpose is achieved: the audience entered and lived in relationship with the perpetual present-absentee.

This exhibit, stage, show, or performance invokes an emotional level, sourced from personal and collective experiences in a political and material reality. 1948 happened. 1967 happened. Oslo happened. Knowing, learning, teaching, and communicating history does not transmit its consequences or the structures of its emotional layers. Here, the artist presents the outcome of an archaeological dig into the spirit of the refugee, unearthing and constructing images to multitudes of layers in the form of angles, looks, appearances, disappearances, seductive perspectives, and desirous gazes towards home. Conjoining myths of ghosts and phantoms with the striking hard realities of a land and its people, the artist articulates thick and intangible emotional dimensions through the walking tour of a depopulated village. A compelling question arises: Why do these supernatural yet real presences resonate and echo in the emptiness of the aftermath of destruction? Halaka would probably say that the energy of the absent figures will resonate in Palestine until and long after they return home.

Through the stages of this exhibit questions are posed, thoughts arise, and feelings surface. Roles switch as the audiences become actors, the artist becomes the subject, the subjects become onlookers, and the transfer of energy and dialog encircles all participants. All sensibilities are challenged. But when the lights in the gallery are turned off, the refugee remains a refugee, the home remains occupied, and the present-absentee continues to struggle for justice. For tonight, keep the lights on. Just for tonight, do not turn them off. It is the least anyone can do.