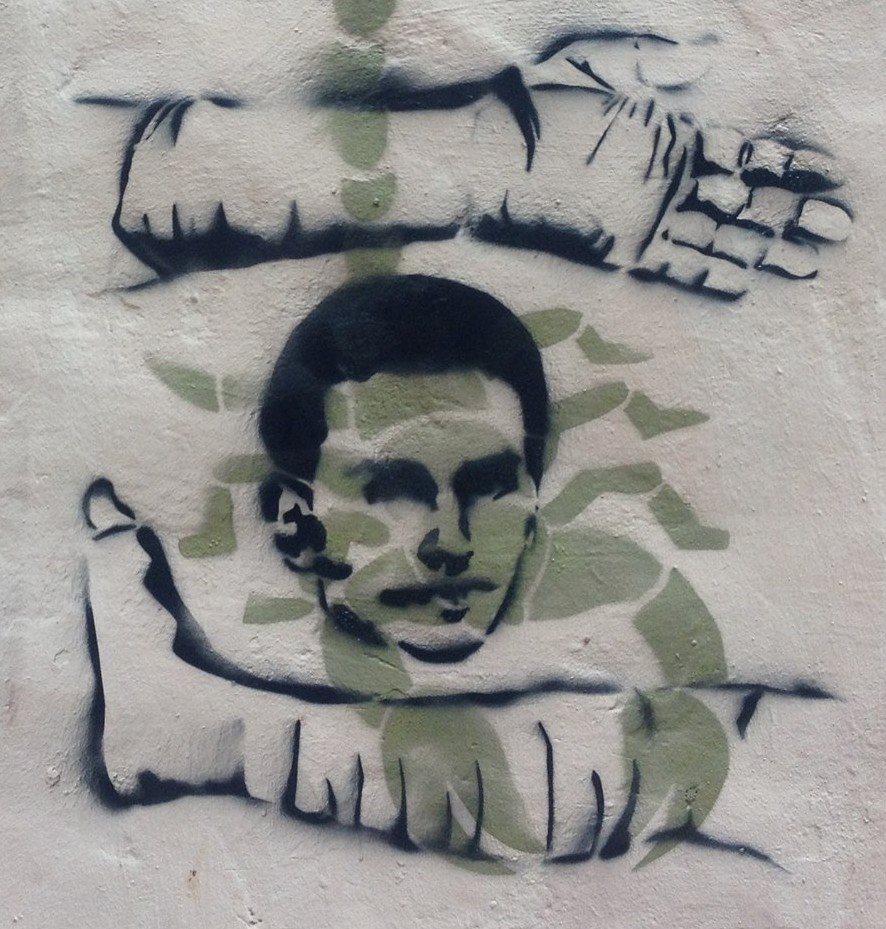

In August 2016, Sabry’s brother sprayed an image of Sabry’s face and bandaged limbs, clasped between the claws of an ominous scorpion, onto a wall in downtown Cairo. Next to it was a piece of text that began: “It is the third Eid that Sabry is spending in prison without having done anything wrong or against the law.” With this graffiti, he publicly appealed to the state for Sabry`s freedom.

“On the day of Arafa and the following four days of Eid, the prisoners are completely locked in,” says Sabry’s mother. Just before Eid 2016, she had made a trip to the Tora maximum security prison, whose grisly reputation has also earned it the name ”Scorpion.” To cover her son’s food for the festive week, she carried with her: pasta, rice, four kilograms of liver, two kilograms of fried chicken, two kilograms of Alexandrian birds, four kilograms of bananas, three kilograms of apples, two kilograms of strawberries, and three kilograms of cantaloupe. In the end only two pieces of liver, two pieces of chicken, two apples and two bananas were allowed in by the officers, and she came back with all the rest.

“Lawyers come and go, judges come and go, and every time my brother goes to court nothing happens, nothing changes,” says Mounir, Sabry’s younger brother flatly. Over three weeks ago, Mohammed Sabry appeared in front of the state security prosecution again, and once again, the judge postponed the case and extended his detention by forty-five days. Amidst the widespread phenomenon of random arrests in Egypt, cases like Sabry’s, which do not entail any crime against the state or act of political dissent, are underrepresented in the media, and endure long periods of uncertainty. Although there is no legitimate evidence to put the suspects in prison, nor to keep them there, Egyptian courts maintain the power to renew detention indefinitely, and the judge`s decision is often pre-determined. As of 16 April, Sabry will have been in this crippling bureaucratic loop for two years, which is legally the maximum time he can be detained.

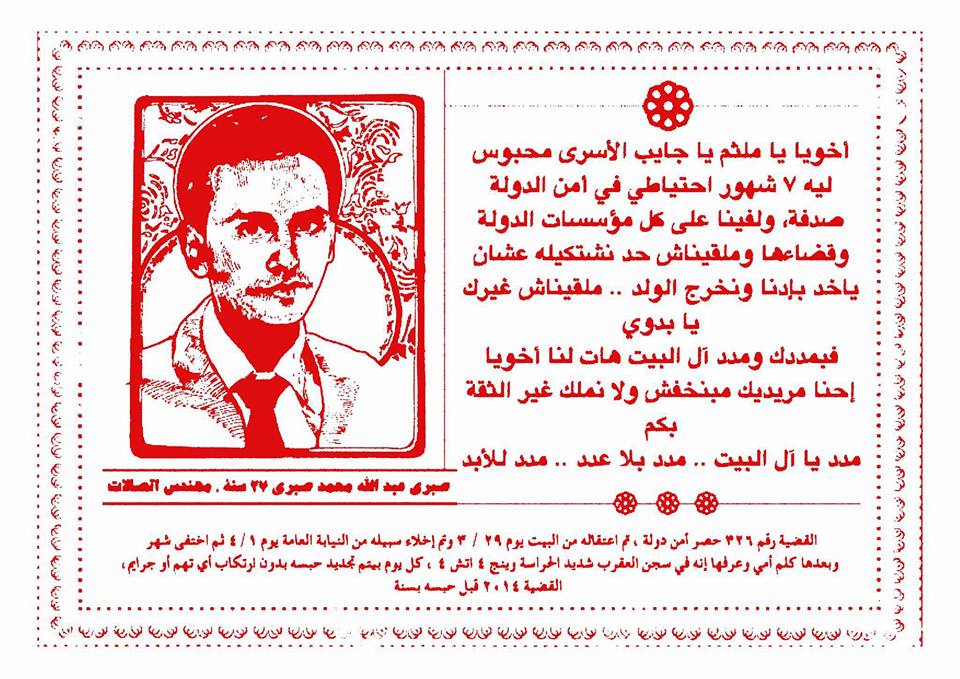

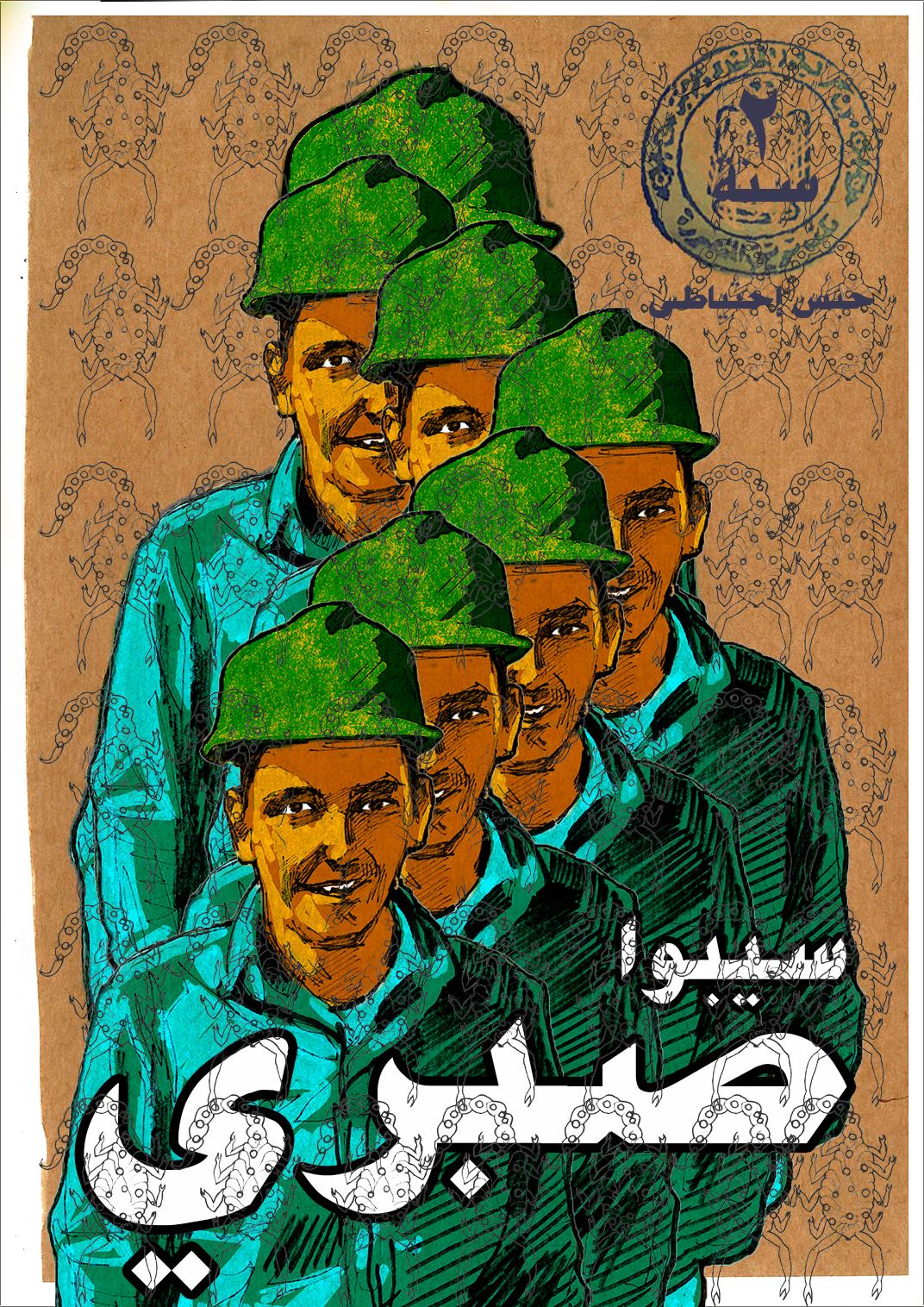

[Poster about Sabry, September 2015.]

In pre-trial detention, the universal right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty is violated and grotesquely reversed. While it should be a preventive last resort, it has become the default political punishment of the Egyptian criminal justice system. The first instance of this type of political abuse under the current regime occurred in 2013, by then-interim president Adly Mansour. The State of Emergency declared after the Raba‘a al-Adawiya massacre saw a surge in numbers of arbitrary arrest and cases of detention, that continued well past the official three month period of Emergency Law. Many are concerned that the newly announced Emergency Law, following the Tanta and Alexandria church attacks of 9 April, will bring a similar wave.

Sabry’s lawyer Ahmed, explains that current laws allow police to detain anyone they presume is a “terrorist,” solely on the grounds of an open investigation. Mohammed Sabry, a young engineer who was soon to be wed, with no affiliation to religious or political groups, has spent almost two years in Egypt’s highest security prison, on the basis of this presumption.

[Public action at the moulid of Sayyid al-Badawi with poster of Sabry, September 2015. Photo by Mounir, Sabry’s brother.]

Sabry was arrested on 29 March 2015 from his home in Cairo. His mother describes how he had just come back from a football match, and was awaiting a food delivery when there was a knock on the door. “He opened it thinking it was the delivery man. Instead we found state security forces, wearing black, armed with rifles and lasers suddenly all over the flat. They asked for his father who was not there at the time.”

One officer demanded to know Sabry’s name, and suddenly a confusion ensued between them about whether his name was Mohammed or Sabry. The officer became angry, and not finding who he was looking for, haphazardly took Sabry with him. His mother recounts: “He told him (Sabry), you’re coming with me, and made him go barefoot. Then I started shouting at the officer and I told him, he will not leave barefoot. I got his shoes and put them on for him, then they took him and left. They also went downstairs and took his father from his grandmother’s flat.”

[Graffiti action, August 2016. Photo by Mounir, Sabry’s brother.]

[Close-up of graffiti design on wall, August 2016.]

Sabry, twenty-six at the time, fits into the extensive demographic of twenty-to-thirty year olds that are the prominent target of random arrests in Egypt. Since this age group arguably carries the most potential to spur oppositional politics, it also becomes the easiest to politically stigmatise. Sabry`s father, who was also arrested in his twenties, experienced a similar injustice. Despite having no connection to political or religious groups, he was also randomly arrested and unfairly imprisoned under the charge of engaging in terrorist activity. The incident took place as part of the mass arrest and incarcerations that swept the country between 1986-7, in reaction to the rising ranks of political Islamists at the time. Since his arrest twenty years ago, Sabry’s father is still regularly harassed by police state security without any legitimate charges. “We do not even have to do anything for them to come to the door,” says Sabry’s mother.

Even though the public prosecution officially issued orders for Sabry’s release and gave his father a fifteen-day jail sentence, Sabry never came home. The family waited for him anxiously. His mother moved out of the house with her other sons, fearing for their safety. She repeatedly went to the public prosecutor’s office asking for Sabry’s whereabouts. “They told me: No, your son got released, go and see where he has gone.” For twenty-one days, no one had any idea where Sabry was, or what had happened to him, until his mother received a phone call from him. She recalls: “He said: Mum, listen to me. I was in Lazoghly and they opened a state security case for me. Now I am going to the state security prosecutor’s office, please find me a lawyer.”

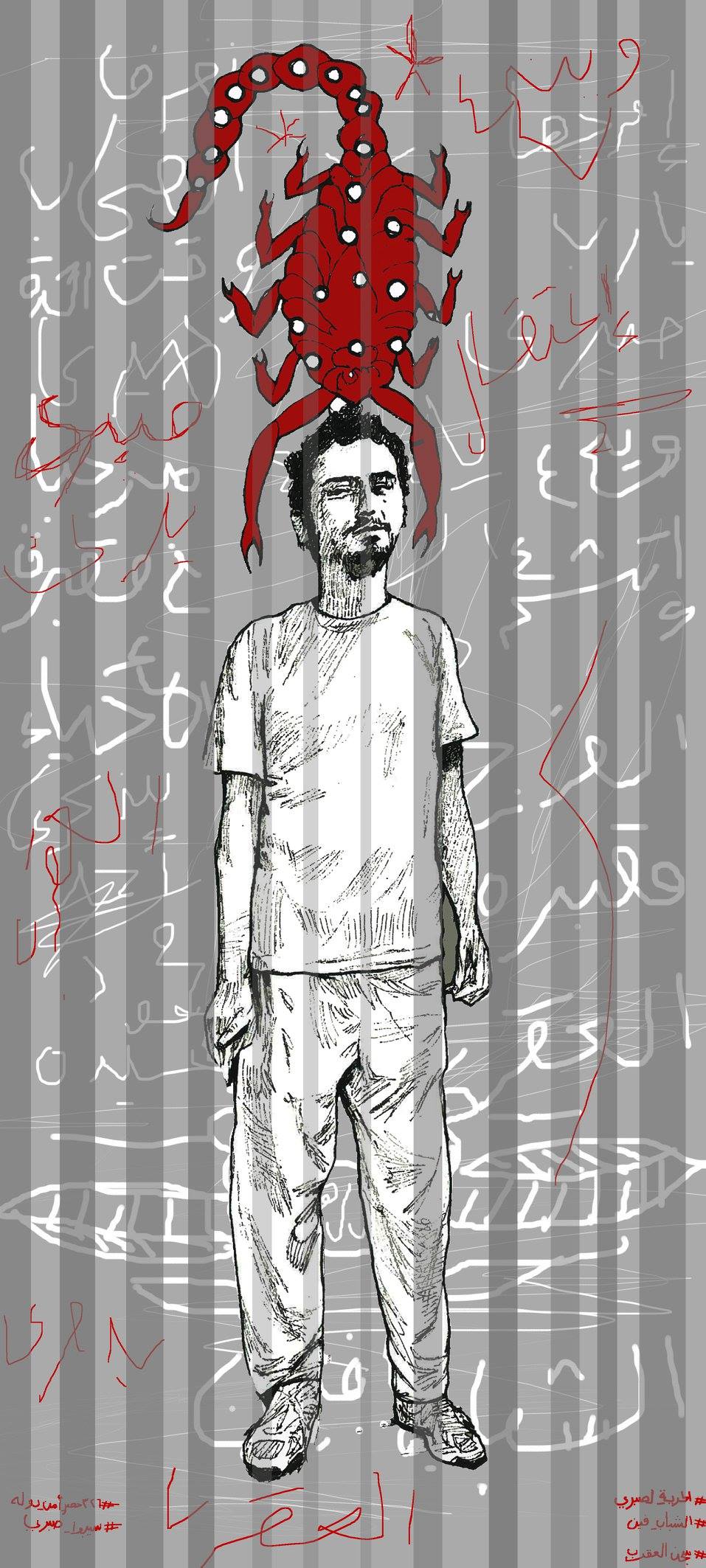

[Design for campaign (Sabry in the Cell), November 2016.]

Under Egyptian law, a suspect must know what they are charged for and be brought before the prosecution within twenty-four hours. However, an enforced disappearance or abduction places detainees outside the protection of the law, which makes it easier for officers to hold them indefinitely, as well as subject them to assault or torture. Sabry told his mother that he had been interrogated without the presence of a lawyer and forced to admit to allegations of involvement in terrorist organizations. His name was added to a case from 2014, already containing around fourteen other suspects to whom he had no relation. All the suspects, apart from Sabry and one other, have now been released following the end of their two-year detention period. “There is no actual event or victim,” his lawyer Ahmed clarifies: “these charges just come from an officer’s existing investigation.” He adds that cases relating to terrorism are the type where the National Security Agency can exercise the most influence over legal proceedings, and in which the largest number of people can be held.

"Terrorism" was not a term used to convict people under Egyptian law until 1992, when the country adopted its first anti-terrorism statute. As a crime, it became punishable under a very vague definition that included "disrupting public order’ and ‘obstructing the work of public authorities." However, a growing tendency towards mass criminalization can be located in political events from the 1981 Emergency Law onwards, within which the widespread arrests of 1987 that Sabry’s father was part of, are prominent example.

Twenty years on, this approach to dealing with political threats became officially sanctioned when "The Fight Against Terrorism" was added as a new chapter in the 2007 version of the constitution. Following this, the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2015 (just a few months after Sabry`s arrest) further granted officers the freedom to detain and arrest without having to comply with the Code of Criminal Procedure in pursuit of counter-terrorist measures. These legal amendments, to highlight a few, demonstrate the widening window of what one can be criminalized for, and an expansion in measures of punishment. The broad and liberally applied accusation of terrorism has become a trap that many like Sabry can fall into by chance, with little room to move thereafter.

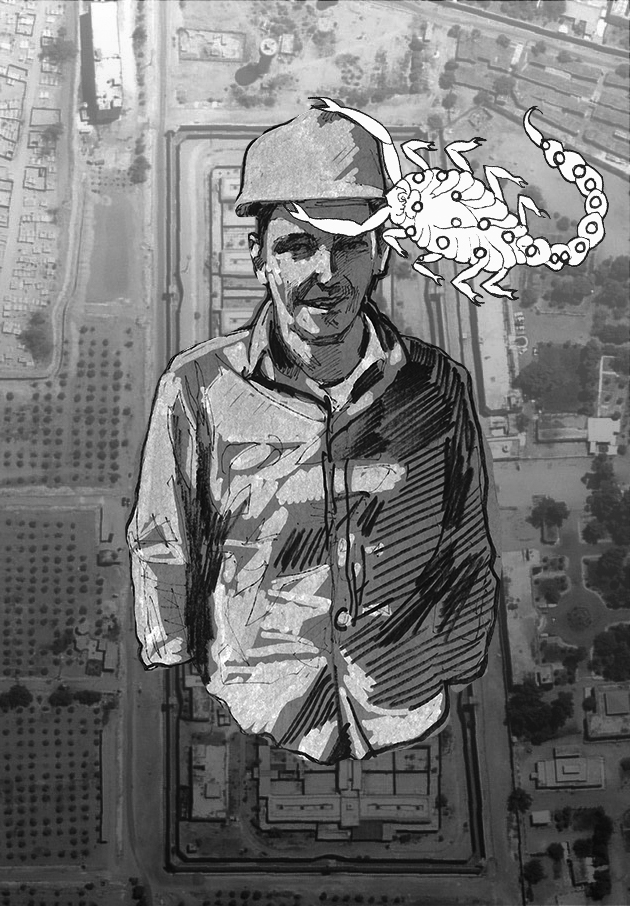

[Design for campaign (Sabry the Engineer over Arial View of the Prison), April 2017.]

After almost two years of Sabry’s confinement in maximum security conditions, his mother admits: “I do not know anything about his life inside; we just say al-hamdulilah.” The Scorpion, or "Egypt’s Guantanamo" as Ahmed refers to it, is the subject of a Human Rights Watch report released in 2016, which outlines its history of abusive practices and living conditions. The prison was, from its inception, designed to host the most dangerous opponents of the state. It is currently home to a mixture of alleged political opponents: Muslim Brotherhood, Islamic State, activists, doctors, and journalists. Amongst these distinct ideological groups, it is hard to see why Sabry, whom his brother describes as “someone interested in football more than politics,” who was “just trying to get married and have a big house,” has ended up there.

“Of course, in the beginning we did not do anything,” says his brother Mounir, who was twenty-two at the time of the arrest. “We just wanted him to be out, so we waited and followed official procedures to file our complaint.” However, as the forty-five days of extended detention began to stack up, their faith in these procedures began to dim. In December 2015, the family received news that Sabry’s leg had been broken after police beat inmates that were partaking in a hunger strike to ameliorate prison conditions. After the incident, Sabry received no medical attention whatsoever. For Mounir, the urge to do something became much more pressing at this point. “I became very depressed and I just became like . . . I did not know what to do. I wanted to find mediums to talk about him in different communities, to make him protected somehow, so there is an eye on him at least.”

In many respects, social media has come to constitute a kind of public “eye” that families use to speak out about their missing loved ones. Although Mounir has created a Facebook page about the case, he believes that actions in the physical, public realm are a more effective way to spread word. He refers to the piece he made on the Eid of 2016 as a "street ad": “It is like if someone goes missing, people make a public announcement about them through posters around the city.” A similar "announcement" was made in the moulid of al-Sayyid al-Badawi, a Sufi saint historically known for releasing prisoners. In the midst of the morning crowds after the Layla al-Kabira (the “great night”), Mounir distributed posters of Sabry to people around the shrine and made a public complaint to al-Badawi about his brother’s situation. He explains: “When you make a complaint to the shrine, you find something you can hold on to, because if you cannot find anything, you lose your mind.”

While Mounir also acknowledges an inherent hopelessness in the unlikelihood that his actions might actually affect the proceedings of the case, his efforts reflect an urgent need to make Sabry present. Considering the vast numbers of existing cases, bulging with unassociated names and identities, and prisons filled with uncounted numbers of bodies—his fears of Sabry becoming lost are rational. “Random arrests and enforced disappearances did take place under previous regimes, but not with this number of people,” Ahmed explains. “It was maybe ten to fifteen cases like this per year, but now it is like the people who have disappeared are more than the number that are being searched for.” As the absence of bodies continually wears upon the social psyche, a normalization of fear and paranoia occurs. If being "present" means not abducted or imprisoned, then for many people in Egypt, this is a state haunted by its own contingency. After what happened, his brother also admits: “even though I did not do anything, I still cannot believe that I am secure.”

However, some people are evidently at a greater risk of disappearing than others. Even on a global scale, the poor and economically marginalized are the most common victims of arbitrary arrest and detention. As people in this position have no social or political influence to facilitate pre-trial release, or to speak out about their injustice, for the state, they can be detained with few repercussions. This also means that the financial weight of having a family member in prison is placed upon those that are already the most strained. While Sabry’s father makes a total of 2500 LE a month in his governmental post, the family spends approximately 1000 LE in visits and 2000 LE on prison food every month, with no idea if this money even gets to him or not. His mother admits that she has to use money from Sabry’s own savings to meet these costs.

[Social media campaign poster, April 2017]

On 16 April 2017, the public prosecution should send a request to the Scorpion prison issuing Sabry’s release, on the grounds that he will have now spent two years in detention. "They can put the suspect on trial just two days before the maximum period of detention ends to give him a sentence. This really happens,” Ahmed says. “But it is also possible that after the two years they release him.” He confesses that it is difficult to say what will happen. Unfortunately, even if Sabry is released, it will be far from a return to normal life. Firstly, there are lifelong implications of having been filed under state security records: being taken once means being easily taken again. In addition, a prison record will severely disadvantage him in terms of finding work, with any form of state compensation out of the question. “He told me he wants to do an MBA,” shares Mounir, “to give him back some of the years he lost.”

Mounir also mentions: “Sabry told me that the first thing he wants to do, if released, is spend some days by the sea in Alexandria or Hurghada, to relax and think about his life.” “Everything will be okay, inshallah,” says his mother, conveying some optimism. However, she is aware that nothing is in her hands, nor the lawyers’. Ultimately, the decision for this case will come directly from the state security prosecution, and at this point, no one has any idea whether Sabry will be getting out or not.

As an appeal to the courts, Sabry’s brother says:

I ask the judge to release my brother Sabry as he did not steal, he did not kill, he did not rape and he did not even speak about politics, but he lost his health, youth and probably his mind within the walls of the Scorpion. Sabry is an engineer who was just beginning his life. His only wishes were to improve himself in his work and position in society. I ask the judge to release him, because he is innocent, and to ensure his safety once he is out.

Sabry’s greater family history highlights how the effects of systematic violence rolls across generations. Families like his, that get caught in the state’s war against its real or fabricated threats, are essentially trapped. Through police profiling, they become the target of future arrests and a type of violence that does not just make a person disappear: it shatters the foundations of a family. The absurdity is that these acts occur under the guise of national security measures. The fact that the family’s own sense of security is destroyed is another matter, and its effect on the number of families in the same position, and on society as a whole, is yet another matter.

In light of President Sisi’s recent re-declaration of Emergency Law, following the church attacks of 9 April, the abuse of police and national security powers is only expected to get worse. While emergency measures allow security forces to arrest and detain people for any period of time, for virtually any reason, Sabry’s story, along with many others, are evidence that this practice already exists, and is employed extensively. Many now gravely anticipate the numbers of future cases, such as this, that look set to appear in the coming months.

[For the purposes of security, certain names have been changed.]