One of the many casualties of Syria’s drawn-out conflict has been empathy. This crisis is particularly acute for what many dub the Syrian “opposition” (al-mu‘aradah). For international observers, the passing of time has seemingly dulled the horror of their suffering and purpose. First, no single actor has successfully positioned itself as the primary defender of the Syrian Revolution. The result is that civil, political, and military actors, with widely diverging visions of Syria’s future, claim to embody the goals of what was, in 2011, a leaderless, spontaneous phenomenon. In addition, the very term opposition conjures a binary that does not exist today. Not all parties to the conflict at present subscribe to the narrative of a contest for sovereignty between an authoritarian regime and a newly-mobilized Syrian public. The projects of the Kurdish PYD and the so-called Islamic State muddle the terms of political struggle in the country. Finally, those who do embrace the label of “opposition” are fragmented spatially across at least five countries—Syria and its neighbor-states of Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, and Iraq. They face enormous logistical hurdles in mobilizing.

Time has thus replaced the early grievances of the opposition with the ambiguity and suspicion that accompany wartime. What many Syrians insisted was a straightforward story of a popular uprising met by state repression is today crowded by characters, subplots, and symbols, all calling for attention. An end to the violence is increasingly viewed as an end in itself. It is for this reason that this story—the story tying a despotic regime to a militarized opposition—deserves more careful consideration, especially in light of the actions and goals of its protagonists. Six years of conflict have buried the Syrian opposition in accusations of incompetence on the one hand, or of being proxies for external interests on the other.[1] But these accusations make the mistake of seeking white knights in a wartime context full of difficult choices and unexpected outcomes. This essay considers how we can still glimpse a decidedly opposition political project amid the fog of war.

Coordination

Ties of coordination are central to understanding the opposition. In a highly disconnected context, much can be learned from considering who talks to one another: the local councils coordinate with armed groups in the territories they govern. The international donors coordinate with logistics contractors, who in turn coordinate with Syrian implementing partners inside Syria. These, in turn, coordinate among the variety of social actors present in a given community.

Thinking about coordination--and those who coordinate—offers insights into the kind of loose relationships that have bound Syrians together beneath the banner of the opposition. These relationships have evolved hand in hand with the situation in Syria. When the uprising militarized in late 2011, it was not long before civilians began hastily arranging aid deliveries to areas “liberated” from the Asad regime. They were supported by diasporic Syrians, who held fundraisers and conducted “mystery shopping” trips to acquire body cameras, satellite internet connections, cameras, bandages, and medicines, which were then smuggled into the country across then-porous borders. With time it became clear that as the regime shifted from a security to militarized response, their piecemeal efforts would eventually be drowned in a sea of blood. In July 2014, as violence increased and opposition-held territories were cut off from social services like water, electricity, and gasoline, the United Nations ratified UN Security Council Resolution 2165, which authorized the delivery of humanitarian aid to Syria via four border crossings: in Turkey, Bab al-Salameh and Bab al-Hawa; in Jordan, al-Ramtha; and in Iraq, al-Yaaroubieh. This had the benefit of scaling up support to areas facing imminent siege, transforming the earlier efforts into hundreds of convoys of carefully-organized trucks passing officially across sovereign borders with UN sanction, stored in guarded warehouses, and distributed within Syria by civil society organizations and logistics contractors.

This did not herald a linear process of consolidating opposition actors. Around that time the National Coalition was founded, which in turn formed the Syrian Interim Government and the Assistance Coordination Unit, based in Gaziantep, an industrial boomtown in Turkey located close to the Syrian border. They were tasked (respectively) with providing services and coordinating the delivery of external humanitarian aid to communities from which the Asad regime had withdrawn. Given their composition of Syria’s intellectual and professional elites, it seemed these bodies were well positioned, institutionally and geographically, to become key intermediaries between the resources afforded by exile and those in need in wartime Syria.

This did not prove to be the case. Neither organization managed to leave a footprint in areas outside regime control,[2] and were instead paralyzed by internal problems. The elite actors behind these large institutions were more fixated on dividing Syria’s imaginary future among the quickly crystalizing political blocs (the Coalition, for example, has four vice presidents), than on the very real, day-to-day struggles of civilians inside Syria. Moreover, their credentials as technocrats did not translate into effective management practices, as few had ever held such positions before 2011 and were largely working professionals.[3] This is compounded by the fact that prior to 2011 the Syrian middle and upper classes (who assumed most of these offices) spent most of their lives circulating between two or three of Syria’s largest cities or living as expatriates in the Gulf countries. They had seldom visited the localities under siege by the regime, which lay in the more modest suburbs and ramshackle countryside of their expansive, diverse homeland. This is true as well for many upper-class anti-regime civil society workers, who describe a humbling process of “discovering” their own country during the revolution and learning to “go to the bottom,” where “everyone else” was.[4]

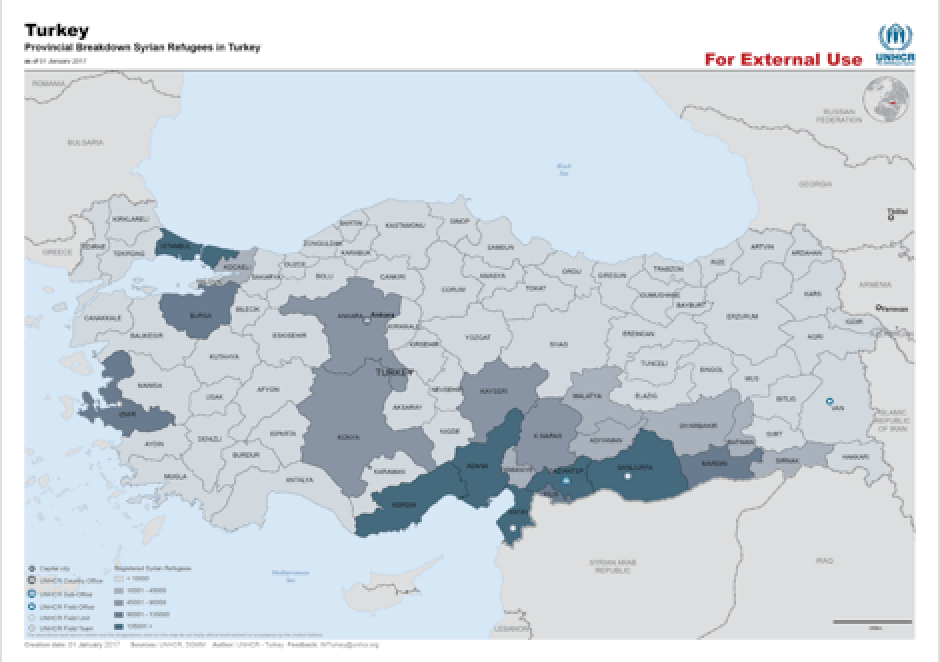

[Figure 1. UNHC map illustrating distribution of Syrians throughout Turkey.

Note the concentrations in Adana, Gaziantep, Hatay, and Sanliurfa provinces.]

Still, we cannot simply attribute the ineffectiveness of these formal opposition institutions to the disconnect of exile. The role meant for these bodies was taken up by a kind of coordinating class that has developed in their shadow, one that has adopted an approach grounded less in administrative hierarchies and more in the cultivation of relationships. For our purposes we might call them a “coordinating class,” a network of actors whose daily practices tie actors inside of Syria to international donor agencies. Cultivating such relationships is essential to forming a capacity to act at a distance and thus produces (albeit sporadically) a political field whose whole is greater than the sum of its parts. This coordinating class thus draws some semblance of a larger mission from the cacophony of political, civil, and military actors operating in opposition-held territory. And it is this class that works most closely with external actors of all stripes. Unlike the formal institutional actors recognized by the Friends of Syria[5] countries, this class is far less likely to get lost in the provinces.

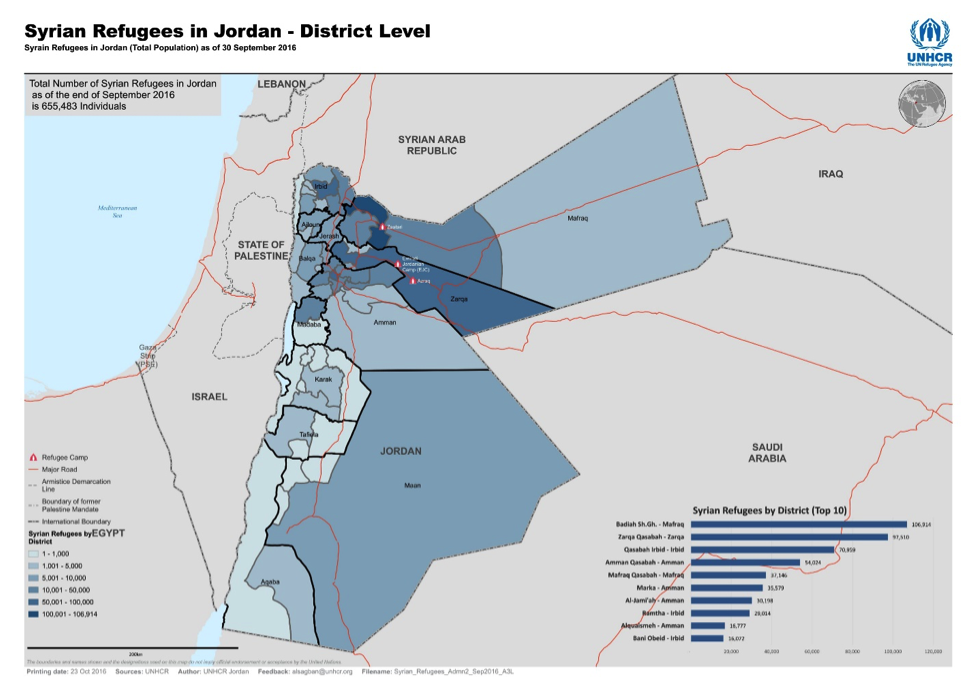

[Figure 2. UNHCR map illustrating distribution of Syrians throughout Jordan.

Note the concentrations in Irbid, Mafraq, and the Amman metropolitan region]

Local Political Horizons

The efforts of the coordinating class are shaped by profoundly local political horizons. These derive as much from pre-2011 governance practices on the part of the regime as they do from novel wartime transformations. Analysts are therefore increasingly attuned to the importance of seeing Syrian politics through the lens of the local (al-mahalli) or via the country’s varied regional landscape (manatiqqiyya); in doing so they sometimes imply the Orientalist notion that Syrian politics are inherently “more local” than elsewhere and therefore require some sort of federal solution. [6] Moreover, the opposition cannot be reduced to an archipelago of communities, since their networks draw extensively on national discourses of duty and belonging, but also international discourses of human rights and global responsibility.[7] The dynamics of Syria’s current opposition landscape are thus very much shaped by far-reaching connections as much as they are by “local politics.” [8] Still thinking through the relevance of the local opens a window into the lived contexts and evolving concerns that structure politics in wartime Syria. It offers a heuristic for thinking through how those forces come together through particular arrangements and how communities engage with them. As a category of practice, then, the local represents an attempt to distill patterns from the fog of war.

Syria’s opposition-in-exile demonstrates very little institutional coherence, but there is instead a very noticeable geography that connects actors inside and outside of Syria. Activists, journalists, diplomats, contractors, militants, and so on move through well-established circuits connecting Gaziantep to Istanbul, Amman, Geneva, and the “liberated” territories. What fails to gather under one institutional roof thus does so instead in the same neighborhood, and (quite literally) in exile. This has resulted in the clustering of a bewildering array of social networks and capacities in space in a way that enables the kind of coordination required to draw materials and other support into opposition-held Syria from without. These shared spaces of socialization in Turkey and Jordan foster dense informal ties among local councilors, activists, and armed groups that contrast with the institutional hierarchies characterizing the Coalition, the Interim Government, and the ACU. After six years in the “village” atmosphere of Gaziantep, the small community of Syrian Opposition actors deepens old friendships and forms new ones, sometimes meeting spouses. By now, many have had children born in exile. A married pair of Syrian journalists in Amman are currently expecting. In the event the child is a boy, they intend to name him Watan (“homeland”).

The “coordinating class” that this shared space gives rise to works to articulate pro-opposition communities in Syria within the “national” movement against Asad. In the early days of the uprising this meant supporting spontaneous civil disobedience, demonstrations, and documenting regime abuses. These efforts were at first organized by the straightforwardly-titled local coordination committees or LCCs (tansiqiyyat), but as the regime shifted from police brutality to military sieges, the nature of the opposition movement changed in tandem. Food and basic services disappeared or turned into regime bargaining chips, and so activists mobilized local councils (majalis mahalliyya) as an experiment in local governance.[9] Although the Coalition in Istanbul tried to co-opt them to bolster its legitimacy, the local councils developed in a highly bottom-up manner due to rapidly-changing events on the ground. This reinforced the intermediary role of the coordinating class. As a result, with time, councils began receiving field visits from activists, consultants, lawyers, medical staff, and journalists; meanwhile, councilors, activists, militants, and women crossed borders into Turkey and Jordan for workshops, trainings, and medical treatment. Even now, as borders grow more securitized, councilors occasionally cross into Turkey to meet with donor organizations, negotiating new projects for water treatment, wheat supply, and so on.[10]

The coordinating class thus links what they refer to as the “liberated” territories to one another and to external support, but it does not do so in a vacuum. A key process destabilizing the stitched-together geography of the opposition is regime bombardment. Opposition actors in exile are not vulnerable to this risk, which in the areas outside government control makes difficult a dignified existence and impossible the consolidation of large-scale institutions like hospitals.[11] Consequently, the opposition suffers from both an institutional weakness, but also a binary spatial imaginary grounded in diverging fates. This binary cuts both ways, with those inside and outside accusing one another of acting as agents (‘umalaa) for foreign states and thus working against the goals of the 2011 revolution. Responding to claims that Operation Euphrates Shield has turned the Free Syrian Army into a proxy for Turkish interests, a journalist embedded with the Levantine Front[12] posted the following statement to his public Facebook page:

A message for everyone claiming that we are just proxies or statistics. We [in the Levantine Front] wake up every morning to smell the sweet air of Syria. When we leave [for campaign], we do not know if we will come back--all for the sake of Syria. We put ourselves in the most uncomfortable situations for the sake of Syria. And if you think that we do not fight the regime, I would like to tell you that the regime killed my father and many of those dearest to me…You can stay in whatever country you are in, happy with your salary from some [other] state and your [operations] room.[13]

Al-Najdi notes the different sources of support to the opposition while highlighting their divergent outcomes. The intensification of hostilities since late 2015 has thus turned an uneasy division of labor between military and civil opposition actors into outright suspicion. Even for the coordinating class, there are limits to politics at a distance.

Temporal Discord

Finally, a number of processes set the rhythm that structures opposition activities, as well as relations between the opposition and the regime. These constitute a set of overlapping, cyclical temporalities that belie the homogenizing progression of time in Syria since violence began. First, there is the halting, long-term temporality of the political process, which begins once every six months or so, only to halt in the face of regime intransigence or other external pressures. Indeed, the recent Geneva IV talks have exposed a deep vein of cynicism in opposition rhetoric but did not prevent the opposition from showing up in Switzerland. Second, while men in suits search for political solutions in some of Europe’s finest hotels, men with guns continue to impose localized fixes that make the terms of peace talks irrelevant. The weekly shifts in battle lines, alliances, and conquests require devoted attention, which explains the ubiquity of “maps of control” as pithy summaries for the current state of Syrian politics.

Third, there is the daily struggle of life in wartime: overcoming the challenges of siege, of arbitrary militia rule, or worse, the imposition of strange institutions, and finding food amid state collapse. Relative unpredictability means that petty crime and food shortages are pushed to the forefront of individuals’ political concerns, rather than the rhetoric of revolution and participatory democracy. This places great pressure on rebel institutions to meet these concerns or risk civilians’ nostalgia for life before the revolution.

Perhaps for this reason the most important temporality shaping Syria’s opposition is the spectacular “break” that anchors the 2011 uprising in the opposition’s historical imaginary. This casts opposition figures as protagonists to a drama in which Syria transforms from “Asad’s estate” into a model for revolutionary change and indigenous democracy. But this narrative comes with high expectations.[14] At best, this epochal shift highlights the gap between the strategic optimism of opposition actors and the limits to coordination, which are considerable. With the opposition unable to secure territory against ISIS convoys or regime air raids, Turkey crossed into Syria on 24 August 2017 to create a “safe zone” (منطقة آمنة) which at present stretches from Azaz in the west to the recently-conquered al-Bab in the eastern Aleppo countryside. With electricity, healthcare, plumbing, and even hot meals provided by Turkey (and Turkish humanitarian organization IHH), the border town of Jarablus has swelled to a small city in a matter of months.

It may go too far to call the area a de-facto protectorate, as many Syrians do, but Turkish involvement certainly upstages the disconnected efforts of opposition actors.[15] For instance, Gaziantep’s provincial governor Ali Yerlikaya is currently overseeing a number of projects typically undertaken by Syrian local councils. Municipal garbage collection and beautification efforts are conducted by a crew from the Municipality of Greater Gaziantep, which crosses over from Turkey every morning at 6 AM and leaves by 5 PM from the Jarablus-Karkamış crossing.[16] On 24 January 2017, an inauguration was held for the Jarablus branch of the Free Syrian Police, in an apparently independent Turkish initiative distinct from the halting American and British-led efforts to do the same.[17] Yerlikaya watched the four hundred fifty trainees on parade in a ceremony that featured strong pledges of gratitude to Turkish President Erdogan, much to the consternation of Syrians in exile.[18] Commenting from Twitter, the angered masses declared that “they have forgotten just how many martyrs we lost to free ourselves of slavery to Bashar [al-Asad]” and warned that Jarablus was on the path to annexation (إلحاق) like the Province of Iskenderun (present-day Hatay in Turkey).[19]

At its worst, the pre-/post-revolution temporality has actively embittered many toward the revolution, especially those displaced into neighboring countries. This is not confined to one class. Many middle-class refugees in Turkey note that the only thing the revolution did for them was deprive them of a comfortable lifestyle and a stable country. And this despite serious anger toward the regime for its brutal campaign of aerial bombardment of civilian areas. Indeed, university professors from Aleppo feature among the merchants working in Gaziantep’s historic market district.[20] The familiar atmosphere hardly sweetens the process of selling scarves to young Turkish couples on holiday from Istanbul.

Inability to harmonize among these different temporalities poses an existential and symbolic threat to the opposition’s political project. The primary mechanisms introduced to draw them into alignment—ceasefires and local truces—are almost instantly violated by regime offensives. The recent capture of East Aleppo struck an enormous symbolic blow. The thousands trapped in the city have become but more internally displaced persons, resettled in Idlib, the regime’s coastal enclaves, or in rare cases, to southeastern Turkey. With this as one’s political horizon, the disruptions of wartime and displacement make the opposition’s narrative of a new revolutionary era difficult to swallow. Rather, the displaced increasingly seek comfort in the abstract dream of return.

The opposition is well aware of the stakes of failure in the “liberated” territories. Should their fragile coordination lapse into outright infighting, the revolutionary experiment of 2011 will be viewed by historians as having died a natural death. But opposition territories have faced unique challenges. Unlike the Kurdish territories and those under ISIS control, opposition areas of Syria are adjacent to regime territories and include Syria’s more populous territory. Consequently, they are exposed to the full wrath of the regime’s aerial assaults, augmented more often than not by Russian and now, American aircraft seeking to punish al-Qa‘ida-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra. And yet, opposition territories are expected to build participatory institutions, maintain a unified military platform, and provide public services, all when outside backers draw them from confronting the regime and toward losing themselves in the margins and subplots of Syria’s ongoing conflict. Little wonder the opposition struggles to maintain its role in a story of overcoming state violence. Its friends have other concerns.

Conclusion

There is nevertheless value in speaking of a Syrian opposition. Opposition actors are brought together by a shared set of cycles, spaces, and a class that coordinates among them. All too frequently, critics attribute the fragmented nature of the opposition to internal incompetence rather than acknowledging the structural forces pulling it apart.

For example, today it is abundantly clear that external support—financial, logistical, even military—is a poisoned chalice. Certainly, American support to local councils has enabled a degree of progress in consolidating civilian institutions in areas outside regime control. A number of projects funded by the US State Department (along with other donor states from the “Friends of Syria” group) support routine services and other programs that stabilize daily life. In day-to-day governance, tangible fruits are being reaped. As one implementer put it, “You do not see an improvement in governance structures or political legitimacy in the short term. That is something that manifests after a few years. And what is nice is that, finally, we are starting to see things moving in the right direction.”[21] Indeed, the Local Council of Azaz has initiated a campaign to keep guns out of civilian areas in an attempt to foster security and maintain arms-length relations with the local armed faction. And in Idlib city, a committee of civilian activists managed to wrest control of municipal governance from Jaysh al-Fatah, the coalition of Islamist armed factions that had long administered the city. Facilitated by the coordinating class, Western donor states have turned the “liberated territories” into a laboratory for participatory governance in Syria.

Only, the laboratory is on fire. The gains mentioned above are meaningless if they are not secured against the constantly changing military landscape of the country. There are two reasons this may be the case. The first is that Syria’s opposition is possibly a victim of policy incoherence among its “friends,” who have created intra-opposition rivalries and pursue half-baked programs that have no place in a warzone. These programs push abstract principles in communities still subject to bombardment from the sky. Community centers are planned, funded, and subsequently targeted, by Russia and the regime. According to a US official working for a program that supports such projects in Syria, attacks like this are a repeated concern threatening their work, but one that they are unauthorized to comment on publicly.[22] If anything, the Trump administration’s recent missile strike against the Assad regime has only deepened ambiguity over American policy toward Syria. President Trump even appeared to confuse Syria for Iraq in a recent interview.[23]

The other explanation is that it is not Syrian communities whose security is of concern, but rather the security of the West. The passing of time suggests that despite rhetoric to the contrary, it is counter-terrorism that dictates the ebb and flow of Western support to the opposition. Foreign governments thus see opposition networks and the local councils they support as partners at best and instruments at worst in the unending and abstract war on terror. Syrians are left struggling to find room for their own political project between the counter-terrorism goals of their “allies,” the constraints of their temporary host states, and the global bureaucracy upholding the nation-state system. Funding is intermittent, its conditions are byzantine, and even the most important members of Syria’s coordinating class are subject to a tangled web of restrictions on mobility. There is little wonder, then, that militants inside Syria are so deeply disillusioned with external actors and the Syrians who collaborate with them from exile. Six years in, then, these contradictions increasingly unmoor Syria’s conflict from the context so vital to understanding its future in the long term. This is because the insistence on counter-terrorism fails to take seriously what kind of terrorism matters in Syria. Unless all key actors are willing to admit that state violence is as high a priority as countering violent transnational extremism, the abstract support they offer for participatory political reform in Syria will do little but stoke more disillusionment with alternative political models. It will normalize state violence on the international stage. And it will reinforce the self-fulfilling prophecy of a fragmented Syrian opposition. On all three points, year seven of Syria’s uprising seems poised to offer new opportunities to miss opportunities.

[1] Debate over the political autonomy of Syria’s opposition movements is bitter, showing no sign of ending, and comes from all quarters. The early years of the Syrian uprising featured attempts to bring together the externally-supported Syrian National Council (championed by many of the “old” opposition figures in exile like Burhan Ghalioun and Michel Kilo) and the National Coordination Committee (NCC), to this day still based in Damascus. Members of the NCC blame opposition figures in exile for leading the country into civil war and strengthening the hand of external actors in domestic politics. Meanwhile, the Building the Syrian State Movement (BSS), another Damascus-based entity, cites both as ineffective, conventional bodies with little popular support. More recently, non-Syrian analysts have accused Syria’s opposition in exile (without differentiating among these) of being pawns in a covert American effort at regime-change in Damascus. Zaydun al-Zoubi, member of the National Coordination Committee. Interview with Author, Gaziantep, January 2017. See also Sam Heller, “Syrian Opposition Politics – with a Lower-Case ‘P.’” (The Century Foundation, 3 January 2017). Max Blumenthal, “Inside the Shadowy PR Firm That’s Lobbying for Regime Change in Syria,” Alternet, 3 October 2016.

[2] In the parlance of Syria’s opposition groups, these areas are referred to as the “liberated territories,” in contrast to most civil war literature, which would describe these as “rebel-held” or “rebel-governed” territories.

[3] Zuhair Sakbani, former participant in the Syrian Opposition Coalition. Interview with author, Gaziantep, December 2016.

[4] A prominent Syrian civil society activist. Discussion with author, Gaziantep, January 2017.

[5] The Friends of Syria Group (also known as the London 11) is a group of states sympathetic to Syria’s opposition movements, in addition to a number of international organizations seeking to provide greater humanitarian support to areas outside of regime control. The United States, Turkey, Jordan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Great Britain number among the participants.

[6] Kheder Khaddour & Kevin Mazur, “The Struggle for Syria’s Regions,” Middle East Report 269 (2015); James Dobbins, Philip Gordon, Jeffrey Martini (2017). “A Peace Plan for Syria III: Agreed Zones of Control, Decentralization, and International Administration,” Rand Institute Perspectives; Samer Araabi, “Syria’s Decentralization Roadmap,” Carnegie Endowment, Sada Middle East Analysis. 23 March 2017.

[7] For instance, the Greater Manbij Political Committee (الهيئة السياسية في مدينة منبج وريفها) is composed of members of the city’s Revolutionary Council who were forced out of the city by the 2014 ISIS invasion, for fear of assassination. Currently in southeastern Turkey, many of these Manbaji opposition figures have transitioned seamlessly to supporting local councils in vastly different communities in the liberated territories. This they justify on the basis that it is all part of a larger revolutionary project. Monzer Sallal, head of the Stabilization Committee of the Aleppo Provincial Council. Interview with author, Gaziantep, February 2017.

[8] Ali Hamdan, “The Displaced as Actors in Syrian Politics,” Middle East Institute, 21 December 2016.

[9] Many attribute the local councils to the writings of Syrian anarchist thinker Omar Aziz. After being arrested in 2012, Aziz died in a regime prison in February 2013. At the same time, local councils pre-existed the 2011 uprising, and their purpose was modified in August of that year through Legislative Decree 107. The councils also build upon pre-existing social networks and dispute-resolution systems.

[10] Director of a Syrian implementing organization. Interview with author, Gaziantep, February 2017.

[11] Syrian American Medical Society, “Aleppo’s Medics under Attack: SAMS Facilities and Medical Equipment in Eastern Aleppo Seized by the Government,” 26 December 2016.

[12] The Levantine Front (al-Jabha al-Shamiyya) is one of the larger branches of the Free Syrian Army. It is active primarily in the northern Aleppo countryside, in particular near the border city of Azaz.

[13] See Saif al-Najdi, free-lance journalist, 12 February 2016 public Facebook post.

[14] Reinoud Leenders, “Master Frames of the Syrian Conflict: Early Violence and Sectarian Response Revisited,” POMEPS workshops, 3 May 2016.

[15] As one Syrian working for a logistics contractor has noted, the Vali of Gaziantep is essentially the first and last authority in the safe zone.

[16] Rajae Hamadeen, field officer for the Independent Doctors Association. Interview with author, Gaziantep, January 2017.

[17] Noticeably, Turkish-trained policemen in Jarablus are armed, while those in Idlib and rural Aleppo are emphatically not. Anonymous employee of a private contractor working with the Free Syrian Police. Interview with author, Gaziantep, January 2017.

[18] Amberin Zaman, “Syria’s New National Security Force Pledges Loyalty to Turkey,” Al-Monitor, 25 January 2017.

[19] Ismail Jamal, “Free Syrian Police Chant for Erdogan and Turkey Raises Controversy among Syrian and Arab Twitter Users,” Al-Quds al-Arabi., 24 January 2017.

[20] Fieldnotes, Gaziantep, 23 January 2017.

[21] Anonymous employee at an international logistics organization. Interview with author, Gaziantep, January 2017.

[22] Naturally, the official prefers to remain anonymous.

[23] Donald Trump, transcript of interview with Maria Bartiromo, Fox Business, 12 April 2017.