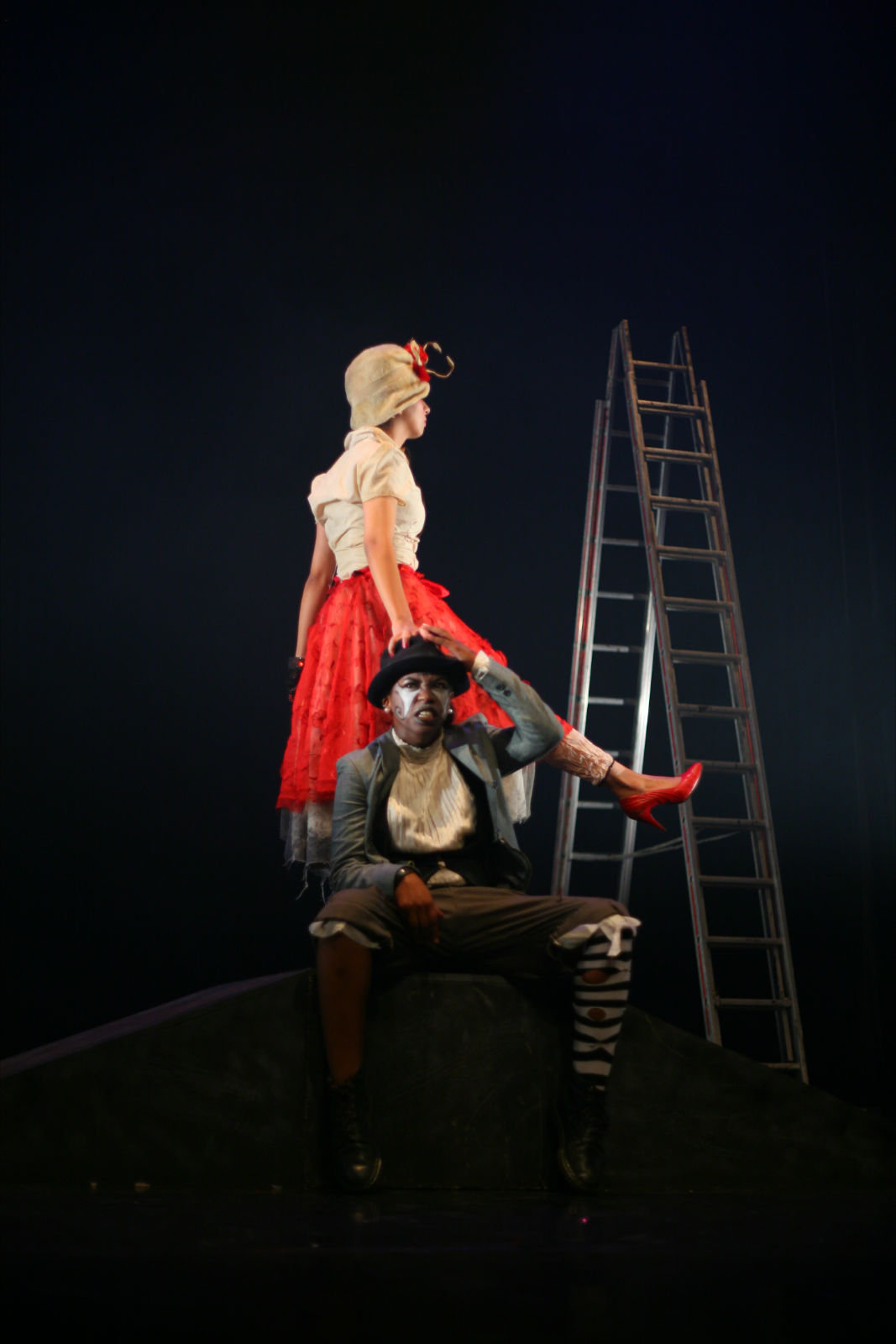

Udi Aloni is a well-known Israeli filmmaker, theatre director, writer and activist, whose most recent work includes films such as Forgiveness, Local Angel, and Kashmir: Journey to Freedom. Columbia University Press just published his new book, What Does a Jew Want?: On Binationalism and Other Specters. I met with Aloni in Ramallah as he was beginning rehearsals for a production of “Waiting for Godot” with students from the Jenin Freedom Theater and continued the conversation in the United States.

The US premier of the production will take place at the Miller Theatre in New York, on 18 October.

Mark Levine (ML): Your book starts off with a seemingly provocative question, one that would seem impossible to answer. How can anyone claim to answer what Jews collectively want, or Muslims or Christians for that matter?

Udi Aloni (UA): The idea for the book arose out of the contradictions that I felt exist between my work as an artist, as a writer, and as an activist. In particular, the difficulty in expressing how one can move from one’s particularity—in my case as an Israeli Ashkenazi Jew—to a universal ethic and aesthetic, and to create a new identity in the process. The task, I suppose, is to show people that you can open yourself to your most dreaded “other,” that you can forge relationships outside of your group that are even more meaningful than the ones that have always defined you.

To do that, I had to accept the position of speaking from weakness and vulnerability, in contrast to the strength Israelis and American Jews imagine they have (but are really afraid that they don`t possess). I argue that from this weakness, we can create new possibilities, or openings.

ML: Edward Said was clearly a big influence on you, it seems. How does a Palestinian thinker help you gain a deeper understanding of your own identity as a Jew?

UA: Said was very important, especially his work Freud and the Non-European and the way he read in Freud, who of course was Jewish, the kind of “unresolved sense of identity” that clearly exists in Israeli and Palestinian identities as well. My book opens with a quote from Said about Freud, asking whether the kind of “deeply undetermined history” of Israel/Palestine could “ever become the not-so-precarious foundation in the land of Jews and Palestinians of a bi-national state in which Israel and Palestine are parts, rather than antagonists, of each other`s history and underlying reality.”

Reading Said`s book was so different from reading a standard academic text. It made me realize the importance of being both intellectual and emotional at the same time, to not allow the two modalities to split our understanding of the realities on the ground. So this led me to ask how I can be totally active, responsible and engaged at the same time as a writer, without losing my art. What Does a Jew Want? is the outcome of this process.

ML: But Freud is seemingly so out of style right now—not just in clinical therapy but as a source of theory. Why is he, and psychoanalysis, so important for you?

UA: For me it comes down to forgiveness, which is also the name of one of my films. I’m`mrawing a line between myselfe nd what I would call a kind of positivist activism in the US. There are people I adore, like Chomsky and others on the lLet, who give the feeling that if you just tell people the truth, stop corporate manipulation, etc., then people will choose the right thing. But this is clearly not the full truth. There is also a trauma zone that prevents the truth from changing people.

Even if you show people the truth time and time again, they will still be blind to it. And so, for example, the demonstrators who march for housing in Tel Aviv could not see the link between their struggle and the Palestinian refugees’ longing for home. American Jews can be so liberal in the United States and yet use proto-fascist language when it comes to Israel.

One possible conclusion is that these people are just evil or duplicitous, but I don`tnbelieve that. Rather, there is clearly a social unconscious that blinds people to the truth. This is beyond changing individual consciousness or having a logical conversation. It can be an infuriating experience to invoke logic and see that people don’t understand your arguments, and this is in part why the lLeftoften becomes so angry and bitter. Psychoanalytic theory helps us understand why people do notn`tnet, so to speak. As Said understood, and as Zizek—who recently worked with me in Ramallah—does too, psychoanalysis offers us tools to dig in, to figure out, to understand what is in all of us that makes us so blind, so hardened to the truth.

ML: Of course, in the Jewish case, the sources of this trauma are clear, centuries of anti-Semitism culminating in the Holocaust. How can art help overcome, or at least transcend, such a powerful trauma that has been so successfully integrated into a colonial-nationalist politics?

UA: For me, art, theory, and action function like the Holy Trinity. The one is three and the three are one. Or perhaps it is better to say: each one is a means for the other and an end in itself. For example, when I come to Palestinians as an Israeli Jew, I don’t come with my ideology only, but also with my identity, my feelings, and my own language, the same way a lover relates to the one he or she loves. I could say that when one tries to be with Palestinians but belongs to the culture that oppresses them, this “being-with” necessitates baring one’s hands and soul like a lover, with all one’s contradictory parts. That is the only way we can attempt to create a true togetherness.

ML: What role does bi-nationalism play in this process, and through it in your book?

UA: When I make my art in order to create a bi-national language, a mutual space for all of us, I have to use all of these tools and bring all sides together, rather than trying to keep them isolated and separate. In this context, the question in the book`s title What does a Jew Want? is like Freud`s question, “What does a woman want?” It is not a question to answer, but rather the start of an investigation, of opening up from this Israeli particularist identity within which I grew up and trying to reach out, beyond the many layers that still prevent us from envisioning a different, more universal identity.

This problem has always plagued the left in Israel, and I suppose in a sense I`m trying to go where the Zionist left failed and, as we say in Hebrew, do a tikkun, or healing for it. At the same time, this process has totally motivated my activism and art—to cross borders, to move to Jenin to teach at the Freedom Theatre, to work and to live with Palestinians. This is part of finding out who I am as a Jew, which is something profound but often seems difficult for others to understand.

ML: Especially if they are still living in a traditional nationalist Jewish or Palestinian identity.

UA: Absolutely, yes. But this is precisely what my relationship with Juliano Mer-Khamis [the well-known film maker and founder of the Freedom Theatre who was assassinated in April of this past year] was based on. He was, because of his parents, both Jewish-Israeli and Palestinian-Arab. Working with him, and the amazing students and colleagues at the Freedom Theater, taught me how to think as a Palestinian Jew—and that`s how you reach bi-nationalism.

ML: What is a Palestinian Jew? It`s a very old term, no? I mean, before 1948, all Jews in Palestine were called that. So it seems like you`re going backward instead of forward with that identity, not to mention constructing an identity that is sure to alienate most Israelis or American Jews.

UA: Well, there are “American Jews” and “French” or “Italian” Jews. Why can`t they understand me as a Palestinian Jew? I am not nationalist anyway, that is not the point. To be within an identity is not something holy; it is the beginning of a discourse, not the end of it. The problem is when people make it dogmatic.

ML: True, Herzl saw Zionism as a means to an end, a tool to end anti-Semitism, not the end in itself.

UA: Yes, exactly! And here, I would say that those who insist on a one-state solution, in an alienated way, based on egalitarian relationships between individuals, are not offering the most viable or even desirable alternative. I use the term bi-national because to say “one state,” like South Africa does not acknowledge the particularity that each community still wants to retain in any solution to the conflict. It does not recognize that we are all in a universal world, but yet, at the same time, we want to build that universality out of particularities, the particular places and cultures in which we stand.

So when I say I am a Palestinian Jew, it means that this is where I begin the dialogue, not necessarily where I want to end up. Said says it so well in Freud and the Non European, where he explains that he does not expect that Jews and Palestinians will become one people, but that within these tensions something new will arise that is one at the same time. In short, this is not a naïve form of universality.

ML: But why not an Israeli Jew? What`s the difference? If identities are the beginning of a conversation, why not begin from an Israeli rather than Palestinian perspective?

UA: Because Israel has a clear border and a clear name, while Palestine is a place that still does not exist as a nation-state, free of occupation. So by calling myself a “Palestinian Jew,” I am connecting myself to what should exist, but doesn’t exist yet. Once it exists, I might choose to be an Israeli Jew again. This is, in a way, my rejection of the liberal/left Zionist discourse [which dominated the Oslo peace process]. It is also a way of rejecting the fantasy of Israeli identity. The reality is that the settlements are the creation of what I call the fantasy element that has for so long dominated the Zionist left, creating what the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde complex of liberal colonialism—the Israeli left/Labor movement portrays itself as the “peace” party yet it was in fact the godfather of the settler movement both before and after 1948.

At the same time, however, people need to realize that Zionism is only the baby sister of concepts like nationalism and colonialism. As you mentioned in previous conversations together, Zionism is a symptom rather than the disease itself.

ML: You mean, it is a cog in the wheel of US empire and neoliberalism, not the operator of the machine.

UA: Yes. So people who put so much energy into fighting Zionism are missing the larger picture. And by complicating the understanding of our identities—by claiming a to be a “Palestinian” Jew when that identity seems unreasonable—I am trying to open the way for people to experience the problematic nature of all our identities, even those that seem much more stable. Only when we do that can we take the crucial step of re-perceiving the other as at the same time a br/other (or sister, of course)--someone who is familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. That is specifically what I ’m trying to do in my work with the hip-hop group DAM, and more recently with Waiting for Godot with the Jenin Freedom Theater.

Udi Aloni

ML: But isn`t bi-nationalism still just a utopian dream with no practical reality?

UA: Look, we are like Noah`s arc; we keep the language of bi-nationalism alive while the Israeli state is becoming more unbearable, more fascist, etc., all the time. But when this discourse finally collapses--and eventually it will have to collapse--we can offer something positive as a new alternative.

In fact it is already starting to happen, with the 14 July social movement that sprang up around the housing protests this summer. On the one hand, it is easy to be cynical, since for the most part the leaders refused to make the obvious connection between social justice for Israelis and the much more basic national justice for Palestinians. Indeed, even the houses of Palestinians in Ramle and Lyd still feel like the tents of 1948, because the residents do not feel at home. The tents of Rothschild Boulevard [where the protests began] may have helped make Israelis who lost their connection to Israel feel at home again, but they won`t be truly home until Palestinians feel at home as well.

And here is the thing: The 14 July protests did not offer a place to deal with the Palestinians’ feeling of exile. One populist speech by Netanyahu at the UN could overcome the power of the movement, at least for now. But the protests did show that people are open to new ideals. And you cannot imagine how important it is that for the first time Israelis did not look to the West and the US as their model, but in fact looked towards young Arabs, towards the revolutions in the Arab world! This is incredible and will have far-reaching implications for Israeli identity in the long run.

Yes, you can be cynical, as some leftists have been, and talk about the “Arab spring without Arabs.” But that misses the huge importance of Tahrir for shaping the identity of a new generation of Israelis.

ML: Do you see any more signs of change within the Israeli public? How has your work with the BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement—which on the surface should have alienated you more from mainstream Israel and Jews—affected this?

UA: Yes, I do. I have been working with the Palestinian hip-hop group DAM for a decade now. And working with them—they live twenty kilometers from Tel Aviv, but in reality this is a world away—has been so transformative. It taught me that in giving myself totally to the Palestinian cause, I was able to inhabit my Jewishness without any problem. This is what people did not understand at first; how or why I could do that. But it is clear now that a new generation of people are emerging who are able to understand that, if we are to solve the huge problems before us, we must reach out beyond the dominant Zionist/Israeli identity.

Here, my work with BDS has been crucial to my personal development. Because I joined BDS, I found a new solidarity, and I was able to open a true dialogue with Palestinians. In Hebrew, there is a play on words here: I moved from seeing Palestinians merely as the “other” (acher in Hebrew)--who according to good left Zionist discourse should be “recognized” and “respected” so long as it doesn`t actually demand anything of Israel--to seeing them as a brother (ach), someone with whom I share a common identity, who shapes me just as I shape him.

I am not trying to be naïve here. I don`t think working with BDS will “bring the revolution,” but we are creating a language that will help us to survive this unbearable present and create an opening to a new understanding. If for no other reason than the fact that this situation cannot last much longer.

ML: Can you talk a bit more about how BDS actually makes much deeper collaboration possible, since most critics of BDS claim it actually prevents collaboration between Israelis and Palestinians?

UA: Because in making this leap, you open yourself up, you create trust, and you can create a new identity. For example, it was precisely in the context of BDS and because of my support for BDS that I could even have the opportunity to work with the Freedom Theatre. It has been particularly intense; Juliano`s death was still so recent, and everyone was in mourning. We chose Waiting for Godot because the play is about the right to mourn and process death rather than immediately moving towards rage. The very hard moments in Godot, they are those small moments of true friendship and fidelity where you feel you hardly have anything; they reflect the possibilities that open up when you take this leap, embrace the other, and become brothers.

After Juliano’s death, we moved the production of the play from Jenin to Ramallah. For me as an Israeli Jew, working in Ramallah with Palestinians who were from Jenin—they were in a way in a kind of exile, double refugees, and we were like a family in mourning together because of Juliano`s death. And in the middle of this, of course, the Israelis seized members of the theatre, including one of the stars of the production, Rami Hwayel. With all of this happening the small gestures that the text of Godot offered us were so crucial.

I want to reveal something here: A day or two before the opening in Ramallah, after we had worked so hard, after everything we did, suddenly someone put up a notice on Facebook calling for a demonstration at the theatre against the production because an Israeli Jew was directing it—their claim was that this was normalization. And the people from Jenin, some of whom, as you know, have been freedom fighters, called them very angrily. They essentially said, “Who are you to make this call, sitting in high society in Ramallah, sipping cappuccino, when we have never had a normal moment in our life?” And the people who started the campaign clearly thought about it because they pulled the Facebook announcement soon after. They in fact admitted that they had not understood the situation. Look at how this one gesture created a whole new dialogue, a new consciousness about the situation, among various people.

I should say, though, that I did not go into Waiting for Godot trying to make great art, but rather out of responsibility to Juliano. And yet it turned out to be great art, not just a good deed. And this is the vision of Said—and of thinkers like Adorno or Benjamin he admired—to create high cultural elements, great art, as the core of a new identity and a new language.

ML: Is this why Slavoj Žižek and American film producer and screenwriter James Schamus came to Ramallah to do a multi-day workshop with young Palestinian artists and activists?

UA: Yes, precisely. Interestingly, there were some very Orientalizing comments from leftists, asking “Why are Zizek and Schamus coming to teach Palestinians instead of listening to them?” But the answer is obvious: Because they are teachers! Because they have knowledge to teach, and there are a lot of intelligent people in Palestine who have the same rights to this knowledge as someone at Columbia University. Of course, we all learned an incredible amount as well. You teach what you know, and you learn what you don`t know. It was so important to the students at the workshop to be in dialogue with them.

It is funny, in a way. Zizek would tease Schamus, who is a well known film producer: “How can you teach Adorno, whose The Culture Industry is basically an attack on all your big budget movies? He would hate your films!” But this is exactly what we were talking about with young Palestinian artists and filmmakers. We asked them, “What do we want? To make Hollywood films? To make a ‘message’ movie about Palestine? Or do we want to MAKE Palestine?” And the answer is that it is good to have both, to understand how to make militant art—as philosopher Alain Badiou explains in his chapter in my book—that comes from “a place of abandoning power, of abandoning victorious ideologies,” and also reaches people with the power of more mainstream film. These conversations are for younger artists and activists.

ML: One would imagine they are the prerequisite for enabling not just strong movements of resistance, but also of transcending—both the occupation and the limited nationalist identities of Israel/Palestine more broadly. Given the success of your work and of the Freedom Theatre, are you in fact hopeful for the future despite all the negative realities of the present?

UA: Yes, I am. Let’s look at BDS. When I first joined about four years ago, people were literally ready to kill me. But now I am not so isolated, and it is `s reat feeling. I know we are losing the fight now, that we are`ret a second away from freedom, as we would ’d e to be. But at least there are people who are beginning to listen. The growing number of Israeli and dDiapora Jews who accept and even work within the BDS framework are becoming less marginalized. We are not merely seen as traitors anymore. Some will say that I`m being utopian or naïve. But I just participated in an amazing panel with other progressive Jewish activists and artists on BDS in a synagogue in Brooklyn. Two hundred and fifty 250s came and the discussion was very well received.

Let`s not think of ourselves as marginalized just because the organized Jewish community says that we are. Indeed, this is why this new book is so important for me. It is an attempt to show people that the debate is no longer between the supposed radical leftist, self-hating Jew and the pro-Israeli one. That framework doesn`t work anymore. Rather, the more you want to be Jewish, the more you should support Palestinians. Or to use a bit of theoretical jargon, the more you want to “perform your particularity,” the more you need perform your universality.

ML: It is like your film Forgiveness, no? You need to ask for forgiveness, and yet forge a new identity that transcends oppression and victimhood at the same time. To not merely deconstruct, as the great philosopher Derrida taught us, but reconstruct something new.

UA: I recall how, when Derrida came to New York to conduct a seminar about forgiveness, we would go to the university to hear his talks, feeling awe-inspired. After the attack of September 11th, Derrida came back to the same class, to conduct the same seminar. But even though the venue was the same, and the seminar was the same seminar, everything was different. The smell of fires from Ground Zero infiltrated the building and engulfed us. Derrida was standing in front of us, a very ill man with his back bent, his white hair having turned even whiter. We realized that the disease had spread to all parts of his body. Someone said he looked like a specter, and it did seem appropriate to speak of him with the term given the importance of that concept in his later work.

But to me he seemed like Paul Klee’s famous Angelus Novus, that famous work displayed at the Israel Museum, which Walter Benjamin rendered into a piece of history in his canonical treatise about the “angel of history.” Benjamin depicts an angel looking back while being propelled forward by an eastern wind. In the place he is looking at, we perceive a chain of events. However, the angel sees their only one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage. All he wishes is to heal the fractures and rectify history. My film Local Angel was born of a confrontation with that angel named Derrida, and my film Forgiveness was born of the wish to hug him and hold back the wind.

And studying with and learning from Derrida led me also to appreciate King. I would like to end this interview with the same prayer that I am ending my book with, from King, who said, “Only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.” Let us pray that the stars we see will not be the missiles over Tel Aviv, Beirut, and Gaza announcing with their shining tails the apocalyptic war bequeathed to us by the Israeli government. Let us hope that the stars are of grace and justice. Stars that can open the gates to our mutual Middle East, For life.

[Note: A shorter version of this interview was published by Al-Jazeera English]